The content

posting practices of young people on social networks

Prácticas adolescentes de publicación

de contenidos en redes sociales

Dr. José Luis Rodríguez-Illera jjlrodriguez@ub.edu. Catedrático de Universidad. Universitat de Barcelona,

España

Dr. José Luis Rodríguez-Illera jjlrodriguez@ub.edu. Catedrático de Universidad. Universitat de Barcelona,

España

Dr. Francesc Martínez-Olmo fmartinezo@ub.edu. Profesor Titular de

Universidad. Universitat de Barcelona, España

Dr. Francesc Martínez-Olmo fmartinezo@ub.edu. Profesor Titular de

Universidad. Universitat de Barcelona, España

Dra. María José Rubio-Hurtado mjrubio@ub.edu. Profesora Titular de

Universidad. Universitat de Barcelona, España

Dra. María José Rubio-Hurtado mjrubio@ub.edu. Profesora Titular de

Universidad. Universitat de Barcelona, España

Dra. Cristina Galván-Fernández cgalvan@ub.edu. Profesora lectora. Universitat

de Barcelona, España

Dra. Cristina Galván-Fernández cgalvan@ub.edu. Profesora lectora. Universitat

de Barcelona, España

Recibido: 2019/09/08

| Revisado: 2019/10/11| Aceptado: 2020/07/02 |

Publicado: 02-01-2021

Cómo citar este artículo:

Rodríguez-Illera,

J.L., Martínez-Olmo, F., Rubio-Hurtado, Mª. J., & Galván-Fernández, C.

(2021). The

content posting practices of young people on social networks. Pixel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, 60, 135-151. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.74025

ABSTRACT

We aim to rethink personal digital storytelling in light of new forms

of communication that have emerged on social networks, as well as to analyse

the core value of image in all of them. Three specific objectives are proposed: i) to know the habits and practices of young

people in relation to the publication of digital (and other) narratives in

social networks, ii) to identify profiles and types of young publishers, iii)

to characterize the differentiating elements between the types of young

publishers. For this purpose, we have designed a questionnaire on young

people’s social network posting practices. The sample corresponds to 835 young

people between 12 and 22 years old from Ibero-American countries (Spain, Chile and Colombia). Our analysis of the results of the

questionnaire shows certain differences according to age, country and gender,

along with several significant similarities. The respondents have been

classified according to posting frequency and type

of posts. Last of all, we make some considerations on how to incorporate the

results of the questionnaire in the training methodology of personal digital

storytelling.

RESUMEN

Se propone repensar los relatos digitales personales (RDP) con las

nuevas formas de comunicación que aparecen en las redes sociales, así como

analizar el valor central de la imagen en todos ellos. Se proponen 3 objetivos

específicos: i) conocer los hábitos y prácticas de los jóvenes con

relación a la publicación de narrativas digitales (y de otro tipo) en las redes

sociales, ii) identificar perfiles y tipos de jóvenes publicadores, iii)

caracterizar los elementos diferenciales entre los tipos de jóvenes

publicadores. Para ello, se ha construido una encuesta sobre las formas de

publicación en esas mismas redes. La muestra corresponde a 835 jóvenes de entre

12 y 22 años de países iberoamericanos (España, Chile y Colombia). Los resultados son analizados, obteniéndose algunas diferencias por edad,

país y sexo, si bien con dosis importantes de similitud. Emerge una

clasificación de los encuestados que los distribuye según la frecuencia y el

tipo de publicaciones que realizan. Finalmente, se proponen algunas

consideraciones sobre cómo incorporar los resultados de la encuesta en la

metodología formativa de RDP y en el campo educativo.

PALABRAS

CLAVES · KEYWORDS

digital storytelling; young people; digital practices; social networks;

digital competence

relatos digitales personales; juventud; prácticas digitales; redes

sociales; competencia digital

1.-

Introduction

Personal digital stories come from the oral tradition of autobiographical forms and life stories, which in the 1990s were transformed by the arrival of new technologies and the capacity to easily produce digital photographs and audio-visual materials. A group of social activists of the Center for Digital Storytelling at Berkeley (Lambert, 2013), renamed the StoryCenter in 2015, came up with the idea of producing some short stories, lasting around three or four minutes, by holding a series of face-to-face, expert-led workshops. The stories, told in the first person, involved a high degree of engagement by the storytellers and held significance for them.

These personal digital stories have begun

to be disseminated online and something of an international movement has been

created with a similar approach to the original stories: non-interactive,

produced by non-experts, priority given to the content (story) being told and

only moderate attention paid to aesthetic and technological aspects. Personal

digital stories express the storyteller’s point of view and voice and are

clearly very subjective. In other words, and from a positive perspective, they

give voice to those who do not normally have one (Burgess, 2006), maintaining

the formal and content-related aspects of personal and autobiographical stories

(Rodríguez-Illera, 2014). In recent years they have generated new theoretical

interest (Erstad & Silseth, 2008; Lundby, 2008) and a good number of

conferences and books have been devoted to the subject (Dunford & Jenkins,

2017; Gregori-Signes & Brígido-Corachán, 2014; Londoño &

Rodríguez-Illera, 2017; Núñez-Janes et al., 2017).

One cannot overstate the importance in

society of the image that creates a kind of spectator audience, a diffused

audience which is always present everywhere and of which we all form a more or

less active part (Abercrombie & Longhurst, 1998). Personal digital stories

occupy a peripheral position in respect of other expressive visual forms, at

least in quantitative terms, perhaps because they explicitly emphasise their

truthful nature, the expression of an aspect of life that is made public and is

disseminated in order to communicate with other people beyond the familiar

environment.

In addition to image and video, the

technological developments of the 21st century have brought about new,

instantaneous forms of communication and interaction, as well as new forms of

connection and ever-present contact through social networks and smartphones. We

believe that this constitutes a new and profound change for personal stories,

including exclusively text-based stories, in the form of instant messages or on

the personal pages of a social network (Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram

and various others). It is a type of change that is taking place in several

other environments, made possible by technology, even if it plays a secondary

role to social aspects; in other words, a shift is taking place from interaction

between machines and people to interaction between people as the core element,

and from interaction to participation in larger human groups.

This phenomenon has led to an exponential increase

in the number of stories found on networks. The stories tend to be shorter,

even containing ephemeral content or abbreviated forms of conventional

storytelling. This becomes immediately evident in a comparison between literary

autobiographies, digital stories and Instagram stories. This increasingly

reduced length is typical of a general movement that shortens but also

simplifies what is being told. Nevertheless, stories told with images continue

to generate a great deal of interest, including those solely featuring still

images as selfies (Warfield, 2015).

These changes in forms of communication, mostly incorporated through social networks, have led us to try to better understand the meaning that young users attach to messages of this kind, especially narrative ones. Although communication patterns between young people have been widely studied, the same cannot be said for personal stories, which remain very similar in conception and in practice to those that were being created more than 20 years ago. Therefore, as we explain below, we have carried out a review of the methodology of traditional personal stories, focusing in particular on their application in formal education, in order to design a questionnaire aimed at trying to find out what young people’s current practices are.

More specifically, the objectives are:

§ To

know what young people’s habits and practices are in relation to the posting of

digital stories (and other types) on social networks.

§ To

identify profiles and types of young posters.

§ To

characterise the elements that differentiate the various types of young

posters.

2.- Methodology

We conducted a survey-based study by means of an online questionnaire that was answered by young people aged between 12 and 22 years old, always in the presence of a member of the research team, between December 2017 and April 2018. The dimensions of the questionnaire are related to aspects that describe traits and behaviours that are significant for the studied phenomenon, such as:

Sociodemographic

characteristics (age, gender, country, education), technological capital and

networks on which respondents have accounts.

Posting

habits: posting frequency and types of post, posting of ephemeral content (type

of content), what respondents add to their posts (themes and elements they

include), with whom they share their posts, being fans/posting on what they are

fans of, knowledge of their followers, source of the content they post,

preparation of posted content, time devoted to creating and posting (editing

time and posting time), topics of posts, frequency with which they post from

each device.

2.1.- Participants

The respondents were selected by means of

a convenience sample made up of 835 young people from Spain (45%), Chile (30%)

and Colombia (25%). Considering a confidence interval of 95% for infinite

populations, where p and q = 0.5, the margin of error in a random sample is ±

3.4%.

Among the respondents, 49.9% identify as

female, 49.5% identify as male and 0.6% identify as non-binary. The average age

of the sample is 16.7 years and almost all the respondents (831 subjects) have

completed studies of one kind or another (from secondary education to

post-compulsory higher education).

Around 92% of the participants possess a computer, 96% have a smartphone, 57% have a tablet, 70.5% state that they have a smart TV (shared with the family) and 93% have an internet connection at home.

The main networks on which they have a

user account are WhatsApp (97.2%), email (92.1%), Instagram (88.5%), Facebook

(76.3%) and YouTube (72.0%). These are followed by a group of networks with a

smaller but still significant number of user accounts among the sample:

Snapchat (54.1%), Skype (52.0%) and Twitter (38.8%). Last of all, the networks

and content applications with a relatively small following are Musical.ly (18.0%),

Blog (17.2%), Telegram (10.3%), Website (6.7%) and Wiki (2.3%).

2.2.- Data

analysis

We used descriptive statistics and mean

comparisons to analyse the data (with robust tests –Mann-Whitney U test– since

the variables do not meet all the parametric assumptions), as well as

proportion tests (C2

). To identify the differential profiles of young producers of digital stories,

we applied the two-step cluster technique. This multivariate classification

technique carries out an analysis designed to detect natural groupings in a

data set (Pérez, 2011). Our aim was to find the best model to classify and

characterise young storytellers, on the basis of the variables related to the

type of content posted by young people and to the posting frequency:

composition of photos or collages, photo gallery, music, individual and/or

group selfies, texts on things that I think or things that happen to me, texts

on things that happen in my environment, videos in which I appear, live videos,

and others (memes, GIFs, etc.).

3.- Results

3.1.-The posting practices of young people on social networks

The posting frequency in general is low,

given the high percentage of respondents who never post, as can be seen in

Table 1. The main types of post are photos and selfies. Ranked below these

types of post (see Table 1).

78.9% of the respondents are fans of

something or someone, but only 21.4% have produced and posted related content.

The posting of ephemeral content (which is

deleted after a certain amount of time) is moderate: 36% of respondents post

such content frequently or very frequently, while only 8.6% always post it.

33.3% of respondents seldom post such content and 22% never do so.

77% of posters create their own content

while 39.52% obtain it from the internet. 61.1% of respondents usually prepare

(edit, adjust) the content they post. 34.4% of respondents devote between one

and four minutes to creating and posting a piece of content, followed by 29%

who devote less than a minute to these tasks and 23% who devote between four

and nine minutes to them. Only 9.7% devote between ten and 60 minutes to

creating and posting content, while a mere 4% devote more than an hour to these

tasks.

The main topics about which the

respondents post are hobbies, tastes and passions (65.8%), followed by places

and spaces (54.1%), important people in their lives (48.7%), aspects of daily

life (47.2%) and important events in their lives (38.4%). A lower percentage of

respondents post content on personal reflections (22.9%), relationships

(21.2%), dreams or personal wishes (15.3%), learning processes, discoveries or

knowledge (12.0%), items or objects of sentimental value (11.6%), and

work-related or professional activities (11.0%).

Types

of post and posting frequency

|

Types of post |

Posting frequency |

|||

|

|

Never |

Monthly |

Weekly |

Daily |

|

Photos |

11.5% |

54.5% |

28.4% |

5.6% |

|

Individual selfies |

34.4% |

40.5% |

19.2% |

6% |

|

Group selfies |

26.8% |

47.9% |

19.5% |

5.7% |

|

Collage |

70.7% |

22.5% |

6.1% |

0.7% |

|

Photo gallery |

60.6% |

26.9% |

5.7% |

0.7% |

|

My videos |

62% |

27.5% |

7.5% |

2.9% |

|

Live videos |

78.6% |

16.2% |

3.7% |

1.6% |

|

Texts on aspects of my life |

69.1% |

18.8% |

8% |

4.1% |

|

Texts on my environment |

69.3% |

18.7% |

8.1 |

3.8% |

|

Texts on fictions |

75.7% |

14% |

6.9% |

3.4% |

|

Music |

70.3% |

14.7% |

7.5% |

7.4% |

|

Others (memes, GIFs) |

50.4% |

20.6% |

12.1% |

16.9% |

The time of day at which respondents post content are very similar between weekdays and weekends and are classified from higher to lower frequency as follows: in the afternoon, in the evening, at midday and in the morning and just after waking up.

64%

of respondents usually share the content they post exclusively with contacts

and/or friends, compared with 28.5% who share it with the general public and

7.5% who only share it with a selection of contacts.

53.1%

of respondents personally know almost all of their followers, while 14.7% know

half of them and 16.5% know some of them. Only 10.9% know all of them and a

very small percentage (4.8%) do not know any of them. Furthermore, the

respondents also follow other people, who they may or may not know personally.

WhatsApp (70.9%), Facebook (66.0%) and Snapchat (52.9%) are the three networks

on which the respondents follow profiles that they know personally. Meanwhile,

the three main networks on which most users follow profiles that they do not

know personally are YouTube (54.1%), Instagram (35.1%) and Twitter (26.5%).

The

main device from which content is posted is the smartphone (88%), followed at

some considerable distance by the laptop, the tablet and the desktop computer,

from which only 12.8%, 10.4% and 5.4%, respectively, post frequently.

3.2.-

Poster profiles

We have been able to classify the 835 respondents into four types of poster. We have carried out the assignment to groups through the two-step cluster technique (Rubio & Vilà, 2016), after completing a regression analysis to identify the variables with a greater predictive degree when it comes to identifying the posting level of each respondent. For the two-step algorithm, we have entered the 12 variables that make up the question corresponding to the frequency with which each type of content is posted1 , which, ranked in order from greater to lesser importance as predictors of the clusters, are as follows: photos, texts on the respondent’s environment, others, individual selfies, group selfies, personal texts, music, personal videos, fiction texts, collages, live videos and photo galleries. The said algorithm has generated four clusters with a good quality index (silhouette measure of cohesion and separation = 0.5). We confirmed the assignment of respondents to each group by means of calculation with the matrix randomly reordered on three occasions and through the index of agreement (kappa = 0.739; p = 0.000) between the assignment of the two-step algorithm and another cluster technique (in this case a hierarchical cluster was applied). As such, we were able to identify the groups listed in Table 2.

Groups

identified according to the content they post

|

Type of poster |

Freq. |

Percentage |

|

Seldom posts (SP) |

308 |

36.9 |

|

Usually posts

photographic and video content (PSV) |

296 |

35.4 |

|

Usually posts text-based,

music-related or other content (GIFs, memes…) (TMO) |

139 |

16.6 |

|

Usually posts all sorts

of content (AS) |

92 |

11.0 |

|

Total |

835 |

100.0 |

Over the course of the study we will refer to the type of poster according to the following key:

Key for type of poster: SP= Seldom posts;

PSV= Posts photos, selfies and videos; TMO= Posts texts, music and other

content; AS= Posts all sorts of content

The age distributions for each type of

poster do not match the normal curve. Significant differences have been found

in average ages (Kruskal–Wallis H test = 10.415; df = 3; p = 0.015): the group

that posts all sorts of content tends to be a little older than the other types

of poster (see Table 3).

Table 3

Age

of each type of poster

|

Type

of poster |

Average |

Standard

Deviation |

|

Seldom

posts |

16.5 |

2.59 |

|

Usually posts photographic and video

content |

16.5 |

2.48 |

|

Usually posts text-based,

music-related or other content (GIFs, memes…) |

16.6 |

2.20 |

|

Usually posts all sorts of content |

17.4 |

2.38 |

|

Total |

16.7 |

2.47 |

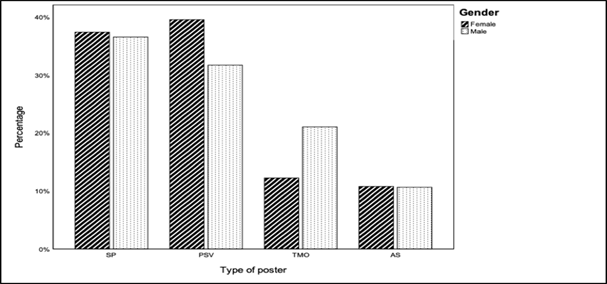

As regards gender, differences have been detected in the types of poster according to this variable (for this calculation five case have been rejected in which the others option was selected in the question about gender; Chi-Square = 13.370; df = 3; p = 0.004; contingency coefficient = 0.126). The type of poster of photographic and video material is characterised by being a mostly female group while the type of poster of text-based, music-related or other content is a mostly male group (see Graph 1)

Graph 1. Distribution of type of poster by gender

As far as countries are concerned, the

respondents from Colombia stand out in respect of those from the other two

countries in terms of posting little or very little, while those from Spain

stand out in respect of those from the other two countries in terms of posting

mostly photos, selfies or videos, or not posting anything at all, and those

from Chile stand out in respect of those from the other two countries in terms

of posting all sorts of content (ChiSquare = 25.192; df = 6; p = 0.000;

contingency coefficient = 0.171).

3.3.- Characterisation of types of poster

In the following sections we describe the

characterisation differentiated according to types of poster.

3.3.1.

Networks on which they have an account

The

analysis of networks on which each type of poster has an account has detected

significant relations in the cases shown in Table 4. For the WhatsApp,

Telegram, blog and email networks, no significant differences have been found.

The type of poster who posts photographic and video content has accounts on the

following networks in particular: Instagram, SnapChat, Skype and Musical.ly.

The type of poster who posts text-based, music-related or other content has

accounts on the following networks in particular:

Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, website and wiki. And, the more general type of poster has an account on all the networks.

Table

4

Networks on which respondents

mostly have accounts according to type of poster

|

|

SP |

PSV |

TMO |

AS |

Chi2 |

p |

C |

|

Facebook |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

17.728 |

0.001 |

0.144 |

|

Twitter |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

14.804 |

0.002 |

0.132 |

|

YouTube |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

10.667 |

0.014 |

0.112 |

|

Website |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

17.856 |

0.000 |

0.145 |

|

Wiki |

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

16.689 |

0.001 |

0.140 |

|

Instagram |

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

21.040 |

0.000 |

0.157 |

|

SnapChat |

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

40.322 |

0.000 |

0.215 |

|

Skype |

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

8.809 |

0.032 |

0.102 |

|

Musical.ly |

|

Yes |

|

Yes |

19.139 |

0.000 |

0.150 |

Note: the

degrees of freedom for all the Chi-Square tests are 3.

3.3.2.

Length of time devoted to social networks

In

respect of the time devoted to social networks, whether on weekdays or at the

weekend, we have observed significant differences (on weekdays: Kruskal-Wallis

H = 55.267; df = 3; p = 0.000, at the weekend: Kruskal-Wallis H = 43.621; df =

3; p = 0.000), which means that the group that seldom posts (SP) tends to

devote fewer hours to networks (most of this group devotes between less than

one hour and three hours to networks on one weekday; and between one and five

hours on one day at the weekend) while the group that usually posts all sorts

(AS) tends to devote more hours to networks than the other groups (most of this

group devotes between one and five hours to networks on one weekday; and more

than five hours on one day at the weekend).

3.3.3.

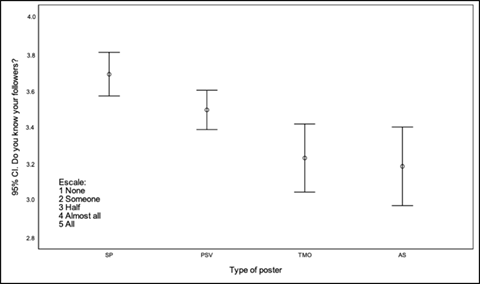

Knowledge of their followers

The

type of poster is related to the degree to which they know their followers.

Those who seldom post content know their followers to a greater degree, while

those who mostly post text-based, music-related and other content, along with

those who post all sorts of content, known their followers to a lesser degree

(Kruskal-Wallis H = 35.643; df = 3; p = 0.000) (see Graph

2).

Graph 2. Distribution of type of poster by gender

3.3.4. With whom they share

their posts

Statistically

significant differences exist (Chi-Square = 31.623; df = 6; p = 0.000), between

types of poster according to whom they share their posts with. As such, we have

observed that the group that seldom posts anything only shares content with a

selection of contacts, while the groups that post photos, selfies, videos,

texts, music and other content mostly share their posts with everybody

(publicly) or only with their contacts or friends, and the group that posts all

sorts of content mostly shares posts with everybody or only with a selection of

contacts

3.3.5. What they add to their posts

Most

of those who post photos, selfies or videos, along with those who post all

sorts, very frequently or always use short texts, emojis, geotags or mentions

to other people in order to add to their posts (see Table 5)

3.3.6. Source of the posted

content

Most

of those who create the content they post belong to the group that posts

photos, selfies or videos (Chi-Square = 18.053; df = 3; p = 0.000; contingency

coefficient = 0.145). The groups that tend to obtain content from the internet

and that retweet, repost, copy or share with other contacts the content they

post are those which mostly post texts, music or other content, and those that

post all sorts of content (Chi-Square = 44.378; df = 3; p = 0.000; contingency

coefficient = 0.225).

Table 5.

Percentage of respondents who very

frequently or always use elements in their posts

|

|

SP |

PSV |

TMO |

AS |

Chi2 |

p |

C |

|

Short texts |

11 |

17 |

12 |

46 |

92.177 |

0.000 |

0.315 |

|

Emojis |

31 |

60 |

32 |

71 |

115.318 |

0.000 |

0.348 |

|

Geotags |

9 |

22 |

6 |

27 |

83.036 |

0.000 |

0.301 |

|

Hashtags |

7 |

13 |

8 |

21 |

57.908 |

0.000 |

0.255 |

|

Mentions to others |

32 |

50 |

28 |

61 |

85.828 |

0.000 |

0.305 |

Note: the

degrees of freedom for all the Chi-Square tests are 12.

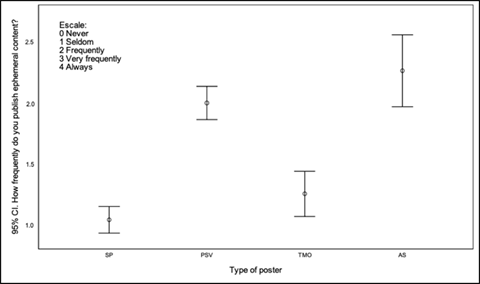

3.3.7. Posting of ephemeral

content

The

frequency with which ephemeral content is posted is greater in the group that

posts photos, selfies or videos and in that which posts all sorts of content

(Kruskal-Wallis H = 127.456; df = 3; p = 0.000) (see Graph 3)

Graph 3.

Frequency with which ephemeral content is posted according to the type of

poster

3.3.8. Preparation of posted

content

The

group that mostly posts photos, selfies or videos tends to prepare with greater

frequency the content it posts than the rest of the groups (Chi-Square =

44.136; df = 3; p = 0.000; contingency coefficient = 0.224).

3.3.9. Time devoted to

creating and posting

As

regards the approximate amount of time devoted to creating and posting content,

we have detected significant differences (Kruskal-Wallis H = 21.793; df = 3; p

= 0.000): those who seldom post content devote less time to creating and

posting (most of them between less than one minute and four minutes), while

those who usually post all sorts of content tend to devote more time to their

posts (most of them between one and nine minutes).

3.3.10. Topics of posts

The

group that mostly posts photos, selfies or videos does so on the topic of

places and spaces with greater frequency than the rest of the groups. The group

that mostly posts textbased, music-related and other content and the group that

posts all sorts of content tend to do so on the topic of hobbies and tastes

with greater frequency than the rest of the groups. The group that posts all

sorts of content tends to post on the rest of the topics asked about in the

questionnaire with greater frequency than the rest of the groups (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Percentage of topics addressed in

content for each type of poster

|

|

SP |

PSV |

TMO |

AS |

Chi2 |

p |

C |

|

Work-related

activities |

9 |

10 |

6 |

27 |

29.102 |

0.000 |

0.184 |

|

Hobbies

or tastes |

57 |

66 |

76 |

78 |

23.345 |

0.000 |

0.165 |

|

Important

events |

30 |

46 |

30 |

53 |

27.725 |

0.000 |

0.179 |

|

Places

and spaces |

44 |

64 |

48 |

63 |

28.525 |

0.000 |

0.182 |

|

Items

of sentimental value |

6 |

12 |

13 |

29 |

39.576 |

0.000 |

0.213 |

|

Important

people |

39 |

58 |

42 |

63 |

31.720 |

0.000 |

0.191 |

|

Learning

or knowledge |

7 |

10 |

14 |

32 |

41.495 |

0.000 |

0.218 |

|

Personal

reflections |

14 |

21 |

24 |

54 |

65.158 |

0.000 |

0.269 |

|

Relationships |

15 |

23 |

19 |

39 |

26.765 |

0.000 |

0.176 |

|

Personal

wishes |

9 |

13 |

23 |

32 |

34.636 |

0.000 |

0.200 |

|

Daily

life |

34 |

54 |

45 |

74 |

53.002 |

0.000 |

0.244 |

Note:

the degrees of freedom for all the Chi-Square tests are 3.

3.3.11. Frequency with which

respondents post from each device

Significant

differences have been found2 according to the type of poster in terms of the

frequency with which respondents post from different devices (desktop computer,

laptop, tablet or smartphone). Most of the respondents never use a desktop

computer or laptop, although the groups that posts text-based, music-related

and other content, and the group that posts all sorts of content use these

devices more than the other groups. The smartphone is the most frequently used

device by all the groups of posters. However, the groups that post photos,

selfies and videos, and the group that posts all sorts of content, use it more

frequently than the other groups. Last of all, we consider it necessary to

indicate that we have not found any specific characterisations (that is, with

significant differences) in the following cases:

- Being a fan of a story

-

Having posted content related

to what/whom one is a fan of

-

Having a WhatsApp account

-

Having a Telegram account

-

Having a blog account

-

Having an email account

-

Posting in the afternoon on

weekdays or at the weekend

-

Posting in the evening on

weekdays or at the weekend

-

Having a smartphone

-

Having a computer at home

-

Having an internet connection

at home

-

- Having a smart TV at home

4.- Discussion

Although these results are

based on a moderate sample of users, they are congruent with other research and

also show us that young people behave similarly in different countries despite

their differences.

5.- Conclusions

Generally speaking, young people are more consumers than posters. The passive/active internet user or consumer/prosumer dichotomy (Tapscot, 1995; Toffler, 1980) has been widely discussed in respect of the possibilities offered by Web 2.0 and social networks, and as such has generated significant expectations in relation to the prosumer group (Aparici & García, 2018; Islas, 2008; Ritzer et al., 2012). However, authors and studies show a different reality. Most internet users post little information; their activity is based on looking at photos, often without sharing their own; listening to music or watching videos, but without leaving comments or signing them by means of social markers; reading tweets and perhaps following a lengthy list of users, but without tweeting. This type of user, also referred to as a lurker (Brown, 2000), is fearful of leaving traces of their internet activity. In contrast to this type of user, active users take on the role of a social subject who creates content in addition to sharing it; a user who is immersed in a social dynamic based on production for exchange (Hernández et al., 2014; Ramírez, 2010).

The most frequent type of post

is the photograph, selfie and video selfie, which is congruent with the

importance of image, as explained above. On social networks, images have

replaced text in many interactions and these interactions are closely

associated with the online habits and behaviours of most young people. As

Sontag (2006) points out, the photograph can be considered an object that

creates the illusion of possession of the depicted experience, place or object.

Fernández and Neri (2008) add that it is not merely a question of capturing the

moment but also of instantly posting it online; that is, an I am being

statement. In respect of selfies, Murolo (2015) argues that the dynamics that

arise in relation to this type of photograph have more to do with a

sociocultural perspective than a technological one, since the telling of a

story that represents the image of oneself in daily life unconsciously

expresses one’s current practices (at the restaurant, at the gym at my graduation

ceremony), personality and personal identity; in a selfie, each person decides

what image to present to the world, and this also encompasses the chosen

background and clothing, and even the digital retouches one applies. To view a

selfie as a personal story is to accept that it has transcended its intrinsic

nature as an image, evolving instead into a communicative artefact that

circulates on social networks. Selfies therefore constitute something more than

mere representation (Gómez & Thornham, 2015); they are little stories

(Georgakopolou, 2016) that emerge as contextualised and co-constructed

presentations of the self, moulded by the media through which they circulate.

In relation to our stated

objective of identifying profiles of young posters and their characterisation,

through the two-step cluster technique we have identified four groups in

respect of types of post and their frequency: a group that seldom posts

content; a group that more frequently posts photographic and video content; a

group that more frequently posts text-based and music-related content; and a

group that posts all sorts of content, this being the smallest group. These

groups possess distinctive characteristics according to the demographic and

contextual variables of the research.

As regards gender, one of the

most significant differences is that young women post more photographic and

video content. This finding coincides with those of studies on the social

networking habits of men and women and shows that young men use social networks

more to have fun, give opinions on issues and produce content, while young

women use them to communicate. Furthermore, young women tend to display

themselves more on social networks through photos and selfies (especially those

aged between 16 and 20 years old) in order to project qualities of beauty

(Manovich, 2013; Porter Novelli, 2012). In respect of country, Chile stands out

as the country where young people post most content in the all sorts category,

while Spain is where they post the most photographic or video content.

It is also noteworthy that the

more time respondents devote to social networks, the greater the variety of

content they post. Therefore, there is a direct correlation between the young

people who invest the most time on social networks and the posting activity on

those networks.

Other characteristics that

differentiate the identified groups are the topics on which they post, the

elements they include in their posts, the type of content and the editing of

this content. As such, as far as topics are concerned, we have found that those

who post content on places and spaces do so using more visual formats (photos,

selfies or videos). These users tend to produce photos, selfies and videos of

the places they visit. They are the creators of this content and usually edit

it (retouching photos, editing videos), as well as embedding short texts,

emojis and mentions to other people. This is also the group that posts

ephemeral content the most, frequently changing photos. In respect of this

aspect, the study by Montes-Vozmediano et al. (2018) ( showed that videos

posted by adolescents focus on places and spaces, mostly having a declarative

structure. Meanwhile, users that post content on hobbies form part of the

text-based, music related or other content group, choosing formats through

which they can write opinions on what they like. These users tend to obtain

content from the internet and to retweet, repost, copy or share with other

contacts the content they post, which is not ephemeral.

Another difference that we

have detected is the degree to which users know their followers and with whom

they share their posts. The less frequently users post content, the more they

share it exclusively with the usual contacts and, therefore, the more they know

their followers. Those who post photos, selfies and videos, and those who post

all sorts of content, tend to share it more with everybody and to know their

followers to a lesser degree. At the same time, they have more followers, since

the more one posts, the more followers one tends to have (Metricool, 2018).

The last distinguishing

element is the device from which content is posted. The smartphone is the

device preferred by all the groups of posters. However, the group that post

photos, selfies and videos, and the group that posts all sorts of content, use

it more frequently than the other groups. The complex ecosystem in which young

people are immersed (instant messaging, forums, blogs, wikis, social networks,

tools for downloading music and series, or for sharing videos and photos, etc.)

requires the application of specific competencies. Young people are generating

and sharing content of different types and levels of complexity, from playing

video games on line to writing fiction, sharing photos on Instagram and videos

on YouTube, explaining ideas on Twitter, etc. A series of skills and elements

of knowledge come into play in these activities, which young people have

acquired outside the academic sphere; for example, from the internet itself,

where all sorts of video tutorials are available. Nevertheless, these skills

are closely associated with technology (for example, creating and modifying

photographic content). In this respect, other pieces of research (Lacasa, 2018)

have identified competencies related to the production, consumption and

post-production of media in the context of youth culture, although unevenly

developed. As such, in the educational community it is necessary to implement

actions geared towards encouraging young people to develop this type of

competencies: competencies that enable users to decode the narrative discourse

in these new media and to create their own, competencies that foster

reflection, participation, engagement and, ultimately, social transformation

through these environments.

One of the strategies is the guided construction of personal digital stories, as has been discussed (Erstad & Silseth, 2008), as well as enabling the expression of one’s own voice (Burgess, 2006; Rodríguez & Anayanzy, 2015), something which achieves good results in both formal and informal education (Londoño & Rodríguez-Illera, 2018). We consider it necessary to adapt this thinking to new posting habits and to the four profiles we have identified and discussed. It is an area that warrants further research.

6.- Funding

Ministerio de

Economia y Competitividad of Spain. Programa Estatal de Fomento de la

Investigación Científica y Técnica de Excelencia. Subprograma Estatal de

generación del conocimiento. Modalidad Proyectos I+D. Project: “Los relatos digitales

en la nueva ecología del aprendizaje“(Ref. EDU2016-76726-P).

References

Abercrombie,

N., & Longhurst, B. (1998). Audiences: A Sociological Theory of Performance

and Imagination. Sage.

Aparici, R., &

García,D. (2018). Prosumidores y emirecs: Análisis de dos teorías enfrentadas. Comunicar, 26(55), 71-79. doi: https://doi.org/10.3916/C55-2018-07

Brown, J. (2000). Growing up: Digital: How the

web changes work, education, and the ways people learn. USDLA Journal, 16(2).

https://bit.ly/2JBUdhH

Burgess,

J. E. (2006). Hearing ordinary voices: Cultural studies, vernacular creativity

and digital storytelling. Continuum: Journal of Media, and Cultural

Studies, 20(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304310600641737

Dunford,

M., & Jenkins, T. (2017). Digital Storytelling, Form and Content. Palgrave.

Erstad,

O., & Silseth, K. (2008). Agency in digital storytelling: Challenging the

educational context. In K. Lundby (Eds.), Digital storytelling,

mediatized stories: Self representations in new media (pp. 213-232).

Peter Lang.

Fernández-Zalazar

D., & Neri C. (2008). Telarañas del conocimiento. Análisis

de los recursos y aplicaciones didácticas de la web 2. Editorial

Libros y Bytes.

Fontcuberta,

J. (2016). La furia de las imágenes. Galaxia

Gutenberg.

Fuente-Prieto,

J., Lacasa, P., & Martínez, R. (2019). Adolescentes, redes sociales y

universos transmedia: la alfabetización mediática en contextos. participativos.

Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 74, 172-196. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1326

Georgakopoulou,

A. (2016). From narrating the self to posting self(ies): A small stories approach

to selfies. Open Linguistics, 2(1),

300-317. http://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2016-0014

Gómez

Cruz, E. (2012). De la cultura Kodak a la imagen en red. UOC.

Gómez, E., & Thornham,

H. (2015). Selfies beyond

self-representation: the (theoretical) f(r)ictions of a practice. Journal of

Aesthetics and Culture, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v7.28073

Gregori

Signes, C., & Brígido Corachán, A.M. (2014). Appraising Digital

Storytelling across Educational Contexts. Publicacions de la Universitat

de València.

Hernández-Serrano,

M.J., Renés-Arellano, P., Graham, G., & Greenhill, A. (2017). From Prosumer to

Prodesigner: Participatory News Consumption. Comunicar, 25(50), 77-88. https://doi.org/10.3916/C50-2017-07

Hernández, D.,

Ramírez-Martinell, A., & Cassany, D. (2014). Categorizando a los usuarios

de sistemas digitales. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 44, 113-126.

http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2014.i44.08

Instituto Nacional de

Estadística, INE. (2016). Población que usa Internet. https://bit.ly/30fnkhu

Islas,

O. (2008). El prosumidor. El actor comunicativo de la Sociedad de la Ubicuidad.

Palabra Clave, 11(1), 29-39.

Lacasa,

P. (2018). Expresiones del futuro. Cómo se comunicarán las próximas

generaciones. Morata.

Lambert,

J. (2013). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community. Routledge.

Londoño,

G., and Rodríguez Illera, J.L. (eds) (2017). Relatos digitales en

educación formal y social. Universitat de Barcelona.

Lundby,

K. (2008). Digital storytelling, mediatized stories: Self-

representations in new media. Peter Lang.

Manovich, L., (coord) (2014). Selfiecity.

Nueva York: OFCC. http://selfiecity.net/#intro

Metricool (2018). Estudio de redes

sociales. Como se han usado las redes sociales en el 2017. https://bit.ly/2PR1w9r

Montes-Vozmediano,

García-Jiménez, A., & Menor-Sendra, J. (2018). Los vídeos de los

adolescentes en YouTube: Características y vulnerabilidades digitales. Comunicar,

26(54), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.3916/C54-2018-06.

Murolo,

N. L. (2015). Del mito del Narciso a la selfie. Una arqueología de los cuerpos

codificados. Palabra Clave, 18(3), 676-700. http://dx.doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2015.18.3.3

Nuñez-Janés,

M., Thornburg, A., & Booker, A. (eds.) (2017). Deep Stories. Practicing,

Teaching, and Learning Anthropology with Digital Storytelling. Gruyter.

Pérez,

C. (2011). Técnicas de segmentación. Conceptos, herramientas y

aplicaciones. Gaceta Grupo Editorial.

Porter Novelli. (2012). The digital gender

divide. https://bit.ly/2JLs7AG

Ramírez-

Martinell, A. (2010). Educational Video: Exploring the complex

relationship between production, educational use and audience. Tesis

escrita para obtener el grado de Doctor en Investigación Educativa. Centro de

Tecnologías Avanzadas de Aprendizaje de la Universidad de Lancaster.

Ritzer, G., Dean, P.,

& Jurgenson, N. (2012). The

coming of age of the prosumer. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(4),

379- 398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211429368

Rodríguez

Illera, J.L. (2014). Personal storytelling in the digital society. In C.

Gregori-Signes & A.M. Brígido Corachán (Ed.) Appraising Digital

Storytelling across Educational Contexts (pp. 41-58). Publicacions

de la Universitat de València.

Rodríguez, F., &

Anayanzy, A.R. (2015). ¡Tu voz no es mi voz! Relato digital: alternativa

para la comprensión de la discapacidad intelectual. https://bit.ly/2koWdRg

Rubio, M.J., & Vilà,

R. (2017). El análisis de conglomerado bietápico o en dos fases con SPSS. REIRE

Revista de Innovación y Recerca en Educación, 10(1), 118-126. http://doi.org/10.1344/reire2017.10.11017

Rugg,

L. (1997). Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography. Chicago

University Press.

Sontag,

S. (2006). Sobre la Fotografía. Alfaguara.

Tapscott,

D. (1995). The digital economy: Promise and peril in the age of

networked intelligence. McGraw-Hill.

Tapscott,

D., & Willliams, A. (2009). Wikinomics. Paidós.

Toffler,

A. (1980). The third wave. Bantam Books.

Universitat de Barcelona.

(2010). Código de buenas prácticas en investigación. Universitat de Barcelona.

Warfield, K. (2015). Digital

Subjectivities and Selfies: The Model, the Self-conscious Thespian and the

#realme. The International Journal of the Image, 6(2),1-16. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-

8560/CGP/v06i02/44167