Hands of the

World intercultural project: developing student teachers' digital competences

through contextualised learning

El proyecto

intercultural “Hands of the World”: desarrollando las competencias digitales de

estudiantes de magisterio a través del aprendizaje contextualizado

Dra. Sharon Tonner-Saunders.

Lecturer. University of Dundee. Scotland

Dra. Sharon Tonner-Saunders.

Lecturer. University of Dundee. Scotland

Dra. Jill Shimi. Senior Lecturer.

University of Dundee. Scotland

Dra. Jill Shimi. Senior Lecturer.

University of Dundee. Scotland

Recibido:

2020/11/23 Revisado: 2020/12/27 Aceptado: 2021/03/16 Preprint:

2021/04/17 Publicado: 2021/05/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Tonner Sunders, S. & Shimii, J. (2021). Hands of the World intercultural

project: developing student teachers' digital competences through

contextualised learning [El proyecto intercultural “Hands of the World”:

desarrollando las competencias digitales de estudiantes de magisterio a través

del aprendizaje contextualizado]. Pixel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, 61,

7-35 https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.88177

ABSTRACT

This paper reports on the impact on student teachers’ professional

skills, knowledge and attitudes of engaging in the eTwinning international

Hands of the World (HOTW) project which connects over 2000 students and their

teachers in 50 schools across the world to undertake a wide range of

educational collaborative work, supported by digital and online

technologies. The University of Dundee’s

HOTW project won the eTwinning prize for the best project two years running and

is the only university to have won this annual prize. Student teachers are

working in a world where digital technology is firmly embedded and undergoing

rapid expansion and change. This study examined the experiences of student

teachers as they engaged in a global project to develop their knowledge and

understanding of intercultural learning using ICT. An explanatory sequential

mixed method design analyzed data publicly available on YouTube™ and Padlet™.

Two main data sets were used: responses to professional development webinars

and reflections on participating in the project. Data were analyzed

thematically focusing on ICT competence, pedagogy and relevance. Participation

in the project enhanced the students' ICT competence and confidence to use and

explore technology for current and future teaching practice through

contextualization and social learning. Our analysis enabled us to identify that

the Covid-19 lockdown had a positive impact on the students' learning due to

time, space, and relevance. This paper demonstrates that engagement in a

contextualized project enabled student teachers to develop their ICT

competences and that for many, lockdown provided a conducive learning

environment.

RESUMEN

El artículo presenta

el proyecto de eTwinning internacional “Hands of the World” (HOTW), que conecta

más de 2000 estudiantes y sus profesores en 50 institutos de todo el mundo para

llevar a cabo una gran variedad de trabajo educativo colaborativo apoyado por

tecnología digital y en línea, y explora el impacto que ha tenido la

participación en el proyecto para los estudiantes de magisterio a nivel de las

competencias profesionales, el conocimiento y las actitudes. Este estudio

examinó las experiencias de los estudiantes de magisterio para desarrollar su

conocimiento y comprensión del aprendizaje intercultural utilizando las TIC al

participar en un proyecto global. La investigación empleando un diseño de

método mixto secuencial explicativo analizó los datos que se encontraban

disponibles públicamente en YouTube™ y Padlet™. Se utilizaron dos conjuntos de

datos principales: las respuestas a los seminarios web de desarrollo

profesional y las reflexiones sobre la participación en el proyecto. Los datos

se analizaron temáticamente centrándose en la competencia de las TIC, la

pedagogía y la relevancia. En las conclusiones se destaca que la participación

en el proyecto mejoró la competencia en las TIC de los estudiantes a través de

la contextualización y el aprendizaje social y su confianza para utilizar y

explorar la tecnología para la práctica de la enseñanza actual y futura.

Nuestro análisis a nivel del tiempo, el espacio y la relevancia nos permitió

identificar que el confinamiento de Covid-19 tuvo un impacto positivo en el

aprendizaje de los estudiantes. Este trabajo demuestra que la participación en

un proyecto contextualizado permitió a los estudiantes de magisterio

desarrollar sus competencias en materia de TIC y que, para muchos, el período

de confinamiento proporcionó un entorno de aprendizaje propicio.

PALABRAS CLAVES · KEYWORDS

ICT, Confidence, Competence, Pedagogy, COVID-19, Student

Teachers

1. Introduction

Student teachers are working within a digital landscape which is evolving constantly and rapidly. A proliferation of digital technology has emerged as a ubiquitous feature of daily life, enabling individuals and communities to connect with each other and to respond to the challenges of global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The notion that digital technology would no longer be a salient feature within our lives was predicted by Weiser (1993) who coined the term ‘ubiquitous computing’. Weiser foresaw that digital technology would become smaller and everywhere: ‘in the walls, on wrists and in ‘scrap computers’ (like scrap paper) lying about to be grabbed as needed’ (Weiser, 1993, p1). The extent to which this has happened was shown in the recent UK Ofcom (2020a) report which focused on the rise of the use of smart technology, stating that in 2020, 51% of people aged 16+ had an internet connected smart TV, compared to 40% in 2019, 22% owned smart speakers and 18% owned smart watches. Alongside the ubiquity of digital technology, Dutton and Blank (2013, p12) highlighted the mobility and accessibility affordances of digital technology where users were becoming ‘less tethered to their desktop computer and more mobile in terms of devices, locations and patterns of use’. This is supported further in an overview by UK Online Measurement (UKOM, 2019) which reported that 64%% of UK adults used smartphones and 11% used tablets while 25% used desktops.

Digital technology is also enabling ‘cross-platform

digital media consumption’ (ComScore, 2013), where users deploy multi-platforms

rather than single devices. In 2019, it was noted that 62%

of UK adults used multi-platforms, compared to 34% using mobile

phones exclusively and 4% making use of

a desktop only (UKOM, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic saw many

human behaviours shifting from face-to-face interactions to online

exchanges for social activities, shopping, work and

education. One third of users’ online time was spent on Facebook

or Google at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, when countries went

into lockdown, entertainment companies, such as

Tik Tok™, Houseparty™ and Zoom™, saw an exponential

increase in usage (Ofcom, 2020b). Educators and students quickly

became key users of technology (Vargo et al. 2020) which created

challenges as many had to learn quickly how to use online platforms and

applications to enable learning to continue remotely (Sun et.

al. 2020). Activities such a as web conferencing were new and

unfamiliar and presented challenges. Higher levels

of stress were identified in teachers in Germany who

were teaching remotely with stress particularly apparent among those who were

teaching for four hours or more online each day (Klapproth et.

al., 2020). Ofcom (2020b) noted that around 559,000 UK children

did not have internet access and 1.8 million children do not have

access to a computer or laptop out of approximately 11,800,000 children. Such

digital exclusion, the lack of access to materials online and the differences

in devices used, all impact on the online learning experience.

Teachers have faced barriers in the use of

technology for many years such

as difficulties in accessing technology and having

inadequate time to develop their digital competence to promote effective

teaching and learning (European Commission, 2019; OCED,

2020). Various researchers and policy

makers have highlighted the importance of developing

teachers’ digital competence skills (European Commission,

2020; Scottish Government, 2016) to enable them to

integrate digital technologies successfully into teaching and

learning within their practice, whether face-to-face or

online, alongside preparing young people to be active citizens

in a digitised world (Klapproth et al., 2020). The

European Commission (2020) acknowledged the importance of teachers being

able to deploy digital

technology ‘skillfully, equitably and effectively’ to

enable an inclusive and high-quality education for all by creating

a Digital Education Action Plan: 2021 – 2027. This follows on

from The European Commission’s European Framework for the Digital

Competence of Educators (Redecker & Punie, 2017), which has

22 digital competences organized into six

areas pertaining to an educators’ professional

competences:

1. Professional engagement

2. Digital resources

3. Teaching

and learning

4. Assessment

5. Empowering

Learners and learners’ competences

6. Facilitating learners’ digital competence.

Teacher Education Institutions (TEIs) are committed to

developing student teachers’ digital technology skills, however, like educators

in other settings, they have encountered challenges, such as workload

demands, lack of digital competence and competing priorities. The obstacles

impeding the integration of technology into TEIs are not new and have been

noted by various researchers over time (Simpson et al., 1998; Sutton,

2011). Many TEIs have developed student teachers’ digital technology skills

through isolated ICT courses or units (Falloon, 2020). This approach has many

positives, however, there it has been criticized for having a

too narrow focus and for not being contextualized (Ferrari,

2012; Janssen et al., 2013). The digital competence of mentor teachers as

they provide support and the student teachers’ limited time using computers

whilst in school have presented further barriers (Grove, 2008). Ryn and

Sandaran (2020) noted that lack of ICT literacy and time limitations continues

to hinder the development of digital skills among teachers. Student teachers have also met with a range

of challenges over the years within schools, such as difficulties accessing

digital technology and a lack of in-school technical support.

The Scottish Government is cognizant of

the need to develop teachers’ skills and confidence in the use of

digital technology to support teaching and learning and seeks to

improve access to all learners (Scottish Government, 2016). The

Scottish Government also acknowledged the importance of student

teachers developing their understanding of the ‘place, purpose

and pedagogy’ of digital technologies for teaching and learning. To

this end, The Scottish Council of Deans of Education were

invited to create The National Framework for Digital Literacies

in Initial Teacher Education (SDCE, 2020). The framework goes beyond

developing student teachers’ digital competence and encourages students to

develop a critical understanding of the pedagogical uses of

technology underpinned by research.

There has been growing awareness of the

need to refocus and move away from teaching basic ICT

skills towards the pedagogy of ICT for over 20 years (Simpson et

al. 1998 & Lambert et al., 2008). The Scottish Government

noted the importance of Teacher Education to promote ‘the benefits of using

digital technology to enhance learning and teaching’ within a wide range

of formal and informal learning opportunities to develop students' digital

skills and pedagogy (Scottish Government, 2016). Firmly embedded in the

General Teaching Council for Scotland’s Standards for Provisional Registration

is the need for student teachers to have knowledge and understanding of digital

technologies to support learning (GTCS, 2021). With this

emphasis on digital technology and the demands for remote teaching and learning

which came into even sharper focus as a result of the

COVID-19 pandemic, it is imperative that student teachers are

supported to develop their digital competence.

2. Methodology

2.1. Context

The study focuses on a global intercultural project,

called Hands of the World: Can You See What I Say (HOTW) (Tonner-Saunders,

2020), which ran during the period of October 2019 to May 2020. The project’s

aim was to create an inclusive learning environment that enabled pupils to

preserve their linguistic identities using music and Makaton signing (Makaton,

2020) and to “work collaboratively to develop an understanding and appreciation

of identities, cultures and languages” (Tonner-Saunders, 2020). The rich

learning that took place within the project, with participation

from over two thousand pupils from over forty schools around the world,

created a learning environment for student teachers to develop their digital

literacy skills through a real live project and CPD opportunities, in the form

of webinars, alongside augmenting their learning through university

inputs and professional literature. Pedagogical approaches and

links to theoretical models of learning such as Vygotsky’s

(1978) constructivist approach and Lave and Wenger’s Communities of

Practice (Wenger, 1998) were embedded firmly in the project to enable

student teachers to make connections with theory and practice. Full

details of the project can be found at: https://bit.ly/37Pe8pL.

2.2. Method

This study focuses on student teachers’ participation

and experiences of developing their digital technology skills through engaging

in HOTW activities and professional development webinars. Documentary evidence,

which Macdonald and Tipton in Gilbert (2008) referred to as social produced

documents from a community at a specific time, was accessed in the form of

student teachers’ comments and reflections which were posted on social media

platforms embedded on the projects’ eTwinning online public space. An explanatory

sequential mixed methods design was deployed, and qualitative data were used to

expand upon initial quantitative data (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

Quantitative data were initially extracted from statistics generated on two

social media platforms used in the project: Youtube™ and Padlet™. The

statistics from these platforms were used to compare the level of student

engagement in webinars throughout the duration of the project. An understanding

of this data was explored through examination of two qualitative data sets of

students' comments and reflections: (i) responses to professional development

webinars and, (ii) reflections on participating in the project’s activities.

2.3. Participants

The population involved were undergraduate and

postgraduate student primary teachers at the University of Dundee who had been

invited to learn about intercultural learning through being a member of

project’s Facebook group, attending or watching professional development

webinars or being active members of the project. As participation in all

aspects of the project was voluntary, the participant numbers varied where some

would participate in multiple activities and others only one, also, some took

an observer role where they learnt from simply reading or watching, whilst

others took a more active role where they left comments, asked questions or

participated in activities. In view of this design, it was possible only to

identify and analyse the number of student responses, rather than the total

number of participants. The number of student responses analysed for the professional development webinars

were: Webinar 1 = 21, Webinar 2 = 39 and Webinar 3 = 71. With regards to the

number of students who participated in the actual project, this research

focuses on a small focus group of 12 students who volunteered to provide

individual reflections pertaining to their ICT development on a separate

Padlet™ page: https://bit.ly/3eRMuwl,

It was not possible to identify the gender or age of

the participants, as individuals provided only their name and the programme on

which they studied.

2.4. Data analysis

A mainly inductive thematic approach was employed to

explore a wide range of open responses that students had provided pertaining to

different aspects of the project (Cresswell & Plano, 2007; Nowell, Norris,

White & Moules, 2017). These were then narrowed down and categorised into

key themes for discussion. Using the qualitative data that was posted online by

the students, a framework analysis (Ritchie & Lewis, 2003) was utilised by

both researchers which involved several stages: (i) both researchers

familiarsing themselves with the data through repeated explorations of the

online posts; (ii) each researcher proposed key themes and negotiated three

higher-order themes for the coding framework: ICT Competence and Confidence,

ICT Pedagogical Knowledge and ICT Application, and (iii) these higher-order

themes were used to code all data using an online spreadsheet which enabled the

researchers to collaborate asynchronously and synchronously. This was an

important factor due to both researchers not working in the same physical

location. From this qualitative and quantitative data gathered, the researchers

were able to discuss how participation in the HOTW project, at whatever level,

assists in developing student teachers’ ICT competence and skills to prepare

them for placements and their future teaching careers.

3. Results

3.1. Project participation

Project participation was through watching the

professional development webinars or participating in the project’s

collaborative activities. The professional development webinars that students

could watch live or the recording at a later date were:

·

Webinar 1: Oct 2019 – Collaborative Learning Through

eTwinning and Online Tools

·

Webinar 2: Jan 2020 - Social Justice Through

Intercultural Learning

·

Webinar 3: Apr 2020 - Learning Through Lockdown

Students were encouraged to leave feedback on the webinar

Padlet pages to share their learning. Table 1 provides an overview of the

number of students who attended the live webinar, watched the recording and

left a response.

Table 1

Number of students who watched or comments on the

webinars

|

Webinars |

Views of webinars |

Responses |

||

|

Total |

Live |

Recording |

||

|

1 |

80 |

19 |

61 |

21 |

|

2 |

71 |

32 |

38 |

39 |

|

3 |

195 |

131 |

64 |

71 |

The number of students who watched the online webinars

(live or recorded) increased during the COVID-19 lockdown period by 160%.

Before lockdown, the average attendance for Webinars 1 and 2 was around 75

students, however, during lockdown this increased to 195 students in April

2020.

This increase is even more prominent in the number of

students who watched the live streaming compared to the recording. Pre-COVID-19

lockdown, more students watched the recording compared to the live streaming:

however, during lockdown viewing behaviours changed and live streaming became

the preferred option. An increase of 424% of live viewing occurred during

lockdown. The average attendance for Webinars 1 and 2, which took place pre

lockdown, was around 25 students, compared to 131 students for Webinar 3 which

was delivered during lockdown. Although the preference was now for the live

streaming version, there was also an increase of 31% of students viewing the

recorded webinars (an average of 49 student’s pre-lockdown compared to 64

during lockdown). With regards to providing a reflective comment, an average of

30 students posted a comment at Webinars 1 & 2 with an increase to 51% to

71 students during lockdown. From the viewing and posting figures above, there

is a clear increase in student webinar participation during lockdown.

With regards to participation in the project’s

activities, the following activities were open to student participation,

whether on placement or individually:

·

A Traditional Postcard with a Modern Twist which used

QR codes, digital media, online platforms to bring the postcards alive.

·

Travelling Ted Teaches the World to Sing which also

used QR Codes, digital media, blogs and communicative online tools.

·

Collaborative song and challenges which used online

platforms, digital media, online voting tools and online presentation tools.

·

The small focus group of 12 students, who left

comments specifically about their ICT development in the above project

activities, are the focus for the data that follows.

3.2. ICT competence and confidence

Most of the focus group students (75%, n-8) noted that

their competence and/ or confidence had risen due to participating in the

project. Their levels of competence varied with two students noting a low level

of competence. Student 1 (Dianne - not her real name) attributed this to being

very nervous when she attended ICT workshops at University due to the fast pace

and feeling incompetent compared to others (Table 2, Quote 1) whilst Student 2

Lisa had a fear of technology resulting in reticence in using for teaching and

learning (Table 2, Quote 2). There were two students who were at the opposite

end of the competence scale who possessed a high level of competence due to

past experiences: one had a background in computing whilst the other was

confident in experimenting with ICT.

Various factors were attributed to raising students'

confidence and/ or competence levels, for example, many students spoke

enthusiastically about the valuable experience of learning from experienced

teachers with Steph reporting that she would not have been successful without

this support (Table 2, Quote 3). Three students who attended the webinars also

commented on how their competence and confidence had grown due to learning from

experienced teachers, making specific reference to online and blended learning,

as narrated by Sarah (Table 2, Quote 4).

Two other key factors described as important were time

and relevance with both directly linked to the outcomes of being in lockdown.

Time was no longer a barrier to many students, as discussed by Nikki and Dianne

(Table 2, Quotes 5-6) who no longer had to travel a considerable amount of time

to University each day. This additional time also worked in the favour of

students who required time to develop their ICT skills and competence, for

example Dianne and Niamh (Table 2, Quotes 7-8). Being able to attend the live

webinars due to time no longer being a barrier, enabled Amy (Table 2, Quote 9)

to be an active learner rather than an observer.

Lockdown also highlighted to many students the

importance of teachers having knowledge and understanding of how to use digital

technologies for teaching and learning, resulting in students seeing a

relevance of focusing on this aspect of their professional development, as

illustrated in Amy, Nikki. Niamh's comments (Table 2, Quotes 10-12).

A marked increase in confidence was noted by two

students, who initially had a very low level of competence. Dianne reported

that she now felt confident to volunteer to work with another teacher in the

project to deliver a lesson online whilst Lisa created digital learning

activities for her local community which she shares in her reflection (Table 2,

Quote 13)

Table 2

Examples of Digital Technology Competence and

Confidence

|

Quote |

Pseudonym |

Data Excerpts |

|

1 |

Dianne |

''...feeling

embarrassed when I did not know what to do.

Others were managing to follow instructions and do things and I was

always needing help.' |

|

2 |

Lisa |

'...

dreading teaching or using ICT with children.' |

|

3 |

Steph |

'I would

not have been able to do this without the guidance and support I was given

from my HOTW teacher.' |

|

4 |

Sarah |

‘Blended learning has

been a bit of a worry for me.... This webinar was really informative and has

eased my concerns about teaching online and using technology.’ |

|

5 |

Nikki |

'Would

I have been able to do this if I was travelling for 90 minutes each way to

university each day, I do not think so, therefore, thanks to lockdown, time

was gifted to me.' |

|

6 |

Dianne |

'Due

to being in lockdown, I had a lot of time on my hands as I no longer had to

travel 3 hours to and from university.' |

|

7 |

Dianne |

'I

spent the next few weeks going back through the recorded webinar and trying

out technology that I thought looked interesting.' |

|

8 |

Niamh |

'...during

lockdown I had young family at home and it was much easier to do lots of

small learning activities rather than having to devote hours.' |

|

9 |

Amy |

'I

found attending the live webinars much more interesting as I could then ask

the teachers questions rather than just watch the presentations. Afterwards, I was then able to try out many

of the ICT tools that were shown due to having the time to do this - benefits

of lockdown!' |

|

10 |

Amy |

'Thank

you for the opportunities to give me the confidence to want to use technology

when I become a teacher, especially in a world where we need to use it more

than we did before.' |

|

11 |

Nikki |

'lockdown

made online learning an important factor in education, I wanted to learn as

much as possibly.' |

|

12 |

Niamh |

'I

felt that the pandemic had opened my eyes to the importance of using ICT to

teach children online and when they are finally back in the classroom.' |

|

13 |

Lisa |

'I became

more confident where I created a QR hunt in my local area for local children

to solve a word challenge. In the

challenge I used a lot of the tools that I had seen in the project, for

example, mentimeter, padlet, SWAY and Google Forms.' |

3.3. ICT pedagogical knowledge

Although there were students who were competent users

of ICT, they did acknowledge that they did not have pedagogical ICT knowledge.

Nikki, for example, who had some knowledge of educational apps due to having a

young family, did not have knowledge of how to use the digital tools

educationally. Similarly, Peter and Louise were knowledgeable in the use of ICT

but not within an educational context, as articulated by Louise (Table 3, Quote

1).

Students spoke positively about developing their ICT

pedagogy through participation in the project and of how they could use digital

technology creatively, collaboratively, inclusively and innovatively, as shared

by Mark, Louise, Peter, Nikki and Hope (Table 3, Quotes 2-6).

Students identified learning from others in the

project's active community of practice Facebook group as a key feature in their

development. Some students such as Gillian, Mark and Peter (Table 3, Quotes

7-9), learnt through observation, and others through questioning, as described

by Lisa (Table 3, Quote 10).

The professional development webinars also contributed

to the students' development of ICT pedagogy. The comments provided in Webinar

1 related to online and/ or collaborative tools (6 responses) whereas in

Webinar 3 there were over 60 responses pertaining to online tools, with

students (n-22) now mentioning term 'blended learning'. Students also referred

to various digital tools that they found interesting or wished to explore

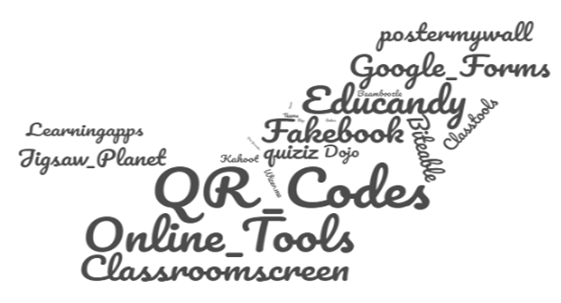

further. The main digital tools students referred to are displayed in Figure 1,

where online tools and QR Codes were the most popular. It was clear from

language used, for example: useful, insightful, helpful, interesting and

informative, that the students gained a great deal from the webinars,

particularly Webinar 3 that focused on online learning.

Table 3

Examples of ICT pedagogical knowledge

|

Quote |

Pseudonym |

Data Excerpts |

|

1 |

Louis |

'Although

I have a high level of expertise in using technology, I do not know all the

applications you can use with children and I do not have the teaching

knowledge that is needed to be able to use the technologies effectively.’ |

|

2 |

Mark |

'One

of the key things I took from the project, was the creative use of ICT and

allowing children to connect with one another in many different ways'. |

|

3 |

Louise |

'My

favourite learning moment was when I saw QR codes make the postcards come

alive...What an wonderful way to use the simplest piece of technology.' |

|

4 |

Nikki |

'Prior

to the HOTW project I did not know how to use technology for collaborative

working, collaborative responses, sharing learning online, managing online

spaces, using tools like QR codes, using blogs with children, content

creation with multimedia tools. |

|

5 |

Peter |

'I've

seen QR codes on many things, however, I would never have thought of using

them to bring learning alive and create inclusive learning.' |

|

6 |

Hope |

'I was

then able to learn how to use many ICT tools that I had never heard of

before, for example, I had never thought of using QR codes in education...To

see the postcards come alive with the QR was an amazing idea. What a

wonderful simple inclusive piece of technology. |

|

7 |

Gillian |

'I

also learnt a great deal from being part of the HOTW facebook (FB) group

where I learnt a great deal from reading teachers' posts where they would

seek support about using the technology.

This made me feel better in that I do not need to know everything

about ICT when I become a teacher'. |

|

8 |

Mark |

'The

FB group was really helpful .…. During lockdown at the beginning, I found this very

interesting as the teachers were all looking for ways to work online.... I felt I learnt as much from the FB group

as I did from the webinars.' |

|

9 |

Peter |

'It

is amazing what you can learn from just reading other teachers' posts!' |

|

10 |

Lisa |

'This

is where the FB group helped as I was able to post questions for help and

immediately teachers in the project or student teachers would respond to give

advice.' |

3.4. ICT application

Students applied what they had learnt in different contexts:

on placement, at home (individually or with others) or online (with a school in

the project), and many saw connections with future practice. One student,

Peter, managed to participate in the Postcard project (one of many projects

available) with his placement class where he had a rich learning experience due

to leading the project, sharing his ICT skills with his mentor and seeing the

children's positive reactions (Table 4: Quote 1). Most students were not able

to take part in the project with a class due to lockdown, however, because the

project was still running online, students had opportunities to work with

teachers and classes around the world. Steph and Gillian's narration of their

learning experience exemplifies the valuable experience that these students had

where they could gain experience of teaching online with the support of an

experienced teacher who knew the class and the technology that would suit their

needs (Table 4, Quotes 2-3). Other students, who had family members at home,

undertook some of the activities with them. This was an interesting social

learning activity for Sarah (Table 4, Quote 4), where multiple people benefited

from Sarah working with her younger brother. Similarly, Amy taught herself how

to make collaborative movies then taught her children how to make them.

Most students in the focus group stated that they were

looking forward to using the digital technology and/or being part of the

project with their next class. Likewise, those who attended the webinars, also

referred to how useful the webinars were for future practice, stating they now

felt more prepared and confident to integrate ICT into their professional

practice, whether that be in the classroom or online (Table 4, Quote 5).

Figure 1

Technology referred to by students after webinars

Table 4

Examples of ICT application

|

Quote |

Pseudonym |

Data Excerpts |

|

1 |

Peter |

'They

loved using all the different technologies and connecting with other schools

around the world. We even managed to

connect online with one of the classes which was a first for them as it was

before lockdown when Zoom was not the fashion! After some technical hitches, I managed to

work out how to connect the pupils about which my class teacher was highly

impressed. |

|

2 |

Steph |

'When

the opportunity was posted to be able to work with a teacher and her class

and teach the class an activity, I was very excited as now I could experience

lockdown teaching...This experience has stuck with me as being one of the

most valuable learning ones I had during lockdown and has made me determined

to be part of this project with my class so that we can work collaborative with

others in exciting ways.' |

|

3 |

Gillian |

'This

was a valuable learning experience as I was able to work with the class

teacher and look at possible technologies to use for the lesson I wanted to

teach.... She also pointed out many

barriers that her pupils could possibly face in a lesson whilst using a

specific piece of technology thus reminding me of digital exclusion at home

and how I had to make learning digitally inclusive.' |

|

4 |

Sarah |

'I

did try many of the activities with my younger brother. I watched the webinars and then he helped

me try out the some of the different tools where he was able to say if he had

used them and how he had. He liked

Google Forms and created quizzes for his peers which resulted in his teacher seeing

them. She now used Google Forms with

his class which was really interesting as everyone was learning together.' |

|

5 |

Hope |

'I

feel this is one of the most valuable ICT skills that I learnt during the

project that I will be able to use whilst a teacher and personally. Since the first lockdown in March, I have

seen so many videos posted online that have lots of people in them from different

locations. |

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Overall, students reported that the project had been useful, interesting, insightful and informative. They expressed gratitude for the opportunity to participate and viewed it as a valuable experience for their professional development and in preparing them for their future teaching practice. Reflections on their experiences demonstrated significant gains in three key areas: the development of ICT competence and confidence, ICT pedagogical knowledge and application of the learning to professional practice.

Across the study there was ample evidence that

students had developed their confidence in relation to the use of digital

technology. Students reported that they had previously lacked faith in their

digital skills but that engagement in the project had increased their to

willingness to engage with digital tools and given them confidence to use their

newfound skills to promote teaching and learning. They cited learning from the

experiences of other teachers and being part of a community of practice as

beneficial to their progress. It was clear that being able to work with

teachers who were already using the technology to support learning, helped them

to envisage how they could use it to enhance their own teaching. Listening to

the experiences of teachers was helpful in that it highlighted the relevance of

the digital technology. Students also cited awareness of new tools as a benefit

of their participation in the project. In their reflections they referred to many

of the tools they had encountered for the first time by name and made

connections in relation to how they could make use of them to support their

professional practice. Students welcomed

opportunities to experiment with the technology informally and found this to be

helpful in the development of their competence. Some referred specifically to

engaging family members in their pursuit of expertise as they trialed new

digital tools.

There was evidence within the project of renewed

determination of students to make use of a wide range of digital tools to

underpin their pedagogical practice. They considered contexts in which the

tools could enhance learning and curricular areas which would benefit from the

inclusion of ICT. This chimes well with the view of the Scottish Government

which stresses the importance of student teachers developing

their understanding of digital technologies for the promotion of teaching

and learning (Scottish Government, 2016). Students identified tools which could

assist them in differentiation, assessment and to develop their students’

writing skills and in comprehension tasks.

They considered ways in which the tools could be used to promote safety

online and how they could be deployed to help them to get to know the children.

Encouragingly, students reported that they were keen to apply their new

knowledge and understanding of digital tools straight away with their families,

in the short term within their placements and beyond that, into their teaching

careers.

Lockdown saw educators and students quickly becoming

key users of technology (Vargo et al., 2020) and it was apparent

that student participation had significantly increased in lockdown in relation

to engagement in both the live webinars and the recordings. A change in student

behaviour was observed in relation to how they engaged. Pre lockdown, higher

numbers chose to view recordings but, during lockdown, live streaming became

more popular. It was interesting to note that students’ vocabulary also changed

during lockdown. The term ‘blended learning’ had not been used in webinars 1

and 2 which were pre-lockdown, but by Webinar 3 this term was used regularly.

Students appreciated the time they could devote to their learning in lockdown

and the fact that they had an appropriate space in which to enhance their

skills. The increase in remote learning

taking place in schools emphasised to them how important it was that they had

the appropriate skills to deliver meaningful online learning opportunities. The challenge now is how maintain this level

of engagement and enthusiasm beyond lockdown. Students would benefit from more

opportunities to undertake real life learning. This would enable them to

appreciate fully the relevance and importance of having a high level of ICT

knowledge and competence to equip them with the skills necessary to embed

technology successfully in their professional practice.

El proyecto intercultural “Hands of

the World”: desarrollando las competencias digitales de estudiantes de

magisterio a través del aprendizaje contextualizado

1.

Introducción

Los estudiantes de magisterio trabajan en un contexto digital que evoluciona constante y rápidamente. La proliferación de la tecnología digital se ha convertido en un rasgo omnipresente de la vida cotidiana, que permite a los individuos y a las comunidades conectarse entre sí y responder a los desafíos de acontecimientos globales como la pandemia del COVID-19. La idea de que la tecnología digital dejaría de ser una característica destacada en nuestras vidas fua anunciada por Weiser (1993), quien acuñó el término "informática ubicua". Weiser preveía que la tecnología digital se haría más pequeña y estaría en todas partes: "en las paredes, en las muñecas y en los ‘ordenadores por piezas’ (reciclados) que se encuentran a su alrededor para utilizar cuando sea necesario" (Weiser, 1993, p. 1). El alcance de este fenómeno se puso de manifiesto en el reciente informe de Ofcom (2020a) del Reino Unido, que se centró en el aumento del uso de la tecnología inteligente, afirmando que en 2020, el 51% de las personas mayores de 16 años disponían de un televisor inteligente conectado a Internet, frente al 40% de 2019, el 22% poseía altavoces inteligentes y el 18% relojes inteligentes. Junto con la ubicuidad de la tecnología digital, Dutton y Blank (2013, p.12) destacaron las posibilidades de movilidad y accesibilidad de la tecnología digital, en la que los usuarios estaban cada vez ‘menos atados a su ordenador de sobremesa y más independientes de los dispositivos, lugares y patrones de uso’. Esto se ve respaldado además por el informe elaborado por UK Online Measurement (UKOM, 2019) que indica que el 64% de los adultos del Reino Unido utilizaban teléfonos inteligentes y el 11% utilizaban tabletas, mientras que el 25% utilizaban ordenadores de sobremesa.

La

tecnología digital también está permitiendo el "consumo de medios

digitales multiplataforma" (ComScore, 2013), donde los usuarios utilizan

multiplataformas en lugar de dispositivos únicos. En 2019, se observó que el

62% de los adultos del Reino Unido utilizaban varias plataformas, en

comparación con el 34% que utilizaba exclusivamente el teléfono móvil y el 4%

que hacía uso únicamente de un ordenador de sobremesa (UKOM, 2019). La pandemia

de COVID-19 ha cambiado muchos comportamientos humanos que pasaron de las

interacciones cara a cara a los intercambios en línea para las actividades

sociales, compras, trabajo y educación. Un tercio del tiempo en línea de los

usuarios se dedicaba a Facebook o Google al comienzo de la pandemia de

COVID-19, sin embargo, cuando los países entraron en confinamiento, las

empresas de entretenimiento, como Tik Tok™, Houseparty™ y Zoom™, aumentaron su

uso exponencialmente (Ofcom, 2020b). Los educadores y los estudiantes se

convirtieron rápidamente en usuarios clave de la tecnología (Vargo et al.

2020), lo que supuso un reto, ya que muchos tuvieron que aprender lo antes

posible a utilizar las plataformas y aplicaciones en línea para permitir que la

educación continuara a distancia (Sun et. al. 2020). Las actividades como las

conferencias web eran nuevas y desconocidas y presentaban un reto. En Alemania

se identificó un nivel más alto de estrés en los profesores que enseñaban a

distancia, un estrés que se hacía particularmente evidente entre los que

enseñaban durante cuatro horas o más en línea cada día (Klapproth et. al.,

2020). En el reino Unido Ofcom (2020b) señaló que alrededor de 559.000 niños no

tenían acceso a Internet y que 1,8 millones de niños no tenían acceso a un

ordenador o a un portátil, de un total aproximado de 11.800.000 niños. Esta

exclusión digital, la falta de acceso a materiales en línea y las diferencias

en los dispositivos utilizados, repercuten en la experiencia de aprendizaje en

línea.

Los

profesores se han enfrentado a barreras en el uso de la tecnología durante

muchos años, como las dificultades de acceso a la tecnología y la falta de

tiempo para desarrollar su competencia digital para promover una enseñanza y un

aprendizaje eficaces (Comisión Europea, 2019; OCED, 2020). Diversos

investigadores y responsables políticos han destacado la importancia de

desarrollar las habilidades de competencia digital de los profesores (Comisión

Europea, 2020; Gobierno de Escocia, 2016) para que puedan integrar con éxito

las tecnologías digitales en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje dentro de su

práctica, ya sea presencial o en línea, junto con la preparación de los jóvenes

para ser ciudadanos activos en un mundo digitalizado (Klapproth et al., 2020).

La Comisión Europea (2020) reconoció la importancia de que los profesores sean

capaces de hacer uso de la tecnología digital "con habilidad, equidad y

eficacia" para permitir una educación inclusiva y de alta calidad para

todos mediante la creación de un Plan de Acción de Educación Digital: 2021 -

2027. Esto sigue al Marco Europeo para la Competencia Digital de los Educadores

de la Comisión Europea (Redecker & Punie, 2017), que tiene 22 competencias

digitales organizadas en seis áreas relativas a las competencias profesionales

de los educadores:

1. Compromiso

profesional

2. Recursos/contenidos

digitales

3. Enseñanza y

aprendizaje

4. Evaluación

5. Fortalecer al alumnado y sus competencias

6. Desarrollo de la competencia digital del

alumnado

Las

instituciones de formación del profesorado (“Teacher Education

Institutions=TEIs) están comprometidos con el desarrollo de las habilidades

tecnológicas digitales de los estudiantes de magisterio; sin embargo, al igual

que los educadores en otros entornos, se han encontrado con problemas como las

exigencias de la carga de trabajo, la falta de competencia digital y las

prioridades contrapuestas. Los obstáculos que impiden la integración de la

tecnología en los TEIs no son nuevos y han sido señalados por varios

investigadores a lo largo del tiempo (Simpson et al., 1998; Sutton, 2011).

Muchos TEIs han desarrollado las habilidades tecnológicas digitales de los

estudiantes de magisterio a través de cursos o unidades TIC aisladas (Falloon,

2020). Este enfoque tiene muchos aspectos positivos, sin embargo, ha sido

criticado por tener un enfoque demasiado limitado y por no estar contextualizado

(Ferrari, 2012; Janssen et al., 2013).

Otros obstáculos han sido la competencia digital de los profesores

mentores a la hora de prestar apoyo y el escaso tiempo que los estudiantes de

magisterio dedican al uso de ordenadores mientras están en la escuela (Grove,

2008). Entre los profesores, en general,

Ryn y Sandaran (2020) señalaron que la falta de conocimientos sobre las TIC y

las limitaciones de tiempo siguen obstaculizando el desarrollo de las

competencias digitales. Los estudiantes

de magisterio también se han encontrado con una serie de retos a lo largo de

los años dentro de las escuelas, como las dificultades para acceder a la

tecnología digital y la falta de apoyo técnico en la escuela.

El

Gobierno escocés es consciente de la necesidad de desarrollar las habilidades y

la confianza de los profesores en el uso de la tecnología digital para apoyar

la enseñanza y el aprendizaje y busca mejorar el acceso a todos los alumnos

(Gobierno escocés, 2016). El Gobierno escocés también reconoció la importancia

de que los estudiantes de magisterio desarrollen su comprensión del

"lugar, propósito y pedagogía" de las tecnologías digitales para la

enseñanza y el aprendizaje. Con este fin, se invitó al Consejo Escocés de

Decanos de Educación a crear el Marco Nacional de Alfabetización Digital en la

Formación Inicial del Profesorado (SDCE, 2020). El marco va más allá del

desarrollo de la competencia digital de los estudiantes de magisterio y anima a

los estudiantes a desarrollar una comprensión crítica de los usos pedagógicos

de la tecnología respaldada por la investigación.

Desde

hace más de 20 años existe una creciente conciencia de la necesidad de

reorientar y pasar de la enseñanza de las habilidades básicas de las TIC a la

pedagogía de las mismas (Simpson et al. 1998; Lambert et al., 2008). El

Gobierno escocés señaló la importancia de la Formación del Profesorado para

promover "los beneficios del uso de la tecnología digital para mejorar el

aprendizaje y la enseñanza" dentro de una amplia gama de oportunidades de

aprendizaje formal e informal para la preparación de los estudiantes en las

habilidades digitales y la pedagogía (Gobierno escocés, 2016). En las normas

del Consejo General de Enseñanza de Escocia para el Registro Provisional está

firmemente arraigada la necesidad de que los estudiantes de magisterio tengan

conocimientos y comprensión de las tecnologías digitales para apoyar el

aprendizaje (GTCS, 2021). Con este énfasis en la tecnología digital y las

demandas de enseñanza y aprendizaje a distancia, que se hicieron aún más

evidentes como consecuencia de la pandemia del COVID-19, es imperativo que los

estudiantes de magisterio reciban apoyo para desarrollar su competencia

digital.

2.Metodología

2.1.

Contexto

El

estudio se centra en un proyecto intercultural global, denominado Hands of the

World: Can You See What I Say (HOTW) (Tonner-Saunders, 2020), que se desarrolló

durante el periodo comprendido entre octubre de 2019 y mayo de 2020. El

objetivo del proyecto era crear un entorno de aprendizaje inclusivo que

permitiera a los alumnos preservar sus identidades lingüísticas utilizando la

música y las señas Makaton (Makaton, 2020) y "trabajar en colaboración

para desarrollar una comprensión y una apreciación de las identidades, las

culturas y las lenguas" (Tonner-Saunders, 2020). En el proyecto ha tenido

lugar un rico aprendizaje, con la participación de más de dos mil alumnos de

más de cuarenta escuelas de todo el mundo, que creó un ambiente de aprendizaje

para que los estudiantes de magisterio desarrollaran sus habilidades de

alfabetización digital a través de un proyecto de un caso real y actividades de

Desarrollo Profesional Continuo, en forma de seminarios web, junto con el

aumento de su aprendizaje a través de las sugerencias de las publicaciones

científicas universitarias y profesionales. Los enfoques pedagógicos y los

vínculos con los modelos teóricos de aprendizaje, como el enfoque

constructivista de Vygotsky (1978) y las Comunidades de Práctica de Lave y

Wenger (Wenger, 1998), se incorporaron con firmeza en el proyecto para permitir

a los estudiantes de magisterio establecer conexiones con la teoría y la

práctica. Los detalles completos del

proyecto pueden encontrarse en: https://bit.ly/37Pe8pL

2.2.

Método

Este

estudio se centra en la participación y las experiencias de los estudiantes de

magisterio en el desarrollo de sus habilidades tecnológicas digitales a través

de la realización de actividades HOTW y seminarios web de desarrollo

profesional. Las pruebas documentales, a las que Macdonald y Tipton en Gilbert

(2008) se refirieron como documentos producidos socialmente por una comunidad

en un momento determinado, se obtuvieron a través de comentarios y reflexiones

de los estudiantes de magisterio que se publicaron en plataformas de medios

sociales integradas en el espacio público en línea de los proyectos eTwinning.

Se empleó un diseño de métodos mixtos secuenciales explicativos y se utilizaron

datos cualitativos para ampliar los datos cuantitativos iniciales (Creswell

& Creswell, 2018). Los datos cuantitativos se extrajeron inicialmente de

las estadísticas generadas en dos plataformas de medios sociales utilizadas en

el proyecto: Youtube™ y Padlet™. Las estadísticas de estas plataformas se

utilizaron para comparar el nivel de participación de los estudiantes en los

seminarios web a lo largo de la duración del proyecto. La comprensión de estos

datos se exploró mediante el examen de dos conjuntos de datos cualitativos de

los comentarios y reflexiones de los estudiantes: (i) las respuestas a los

seminarios web de desarrollo profesional y, (ii) las reflexiones sobre la

participación en las actividades del proyecto.

2.3.

Participantes

La población

implicada eran estudiantes de grado y postgrado de Magisterio de la Universidad

de Dundee que habían sido invitados a aprender sobre el aprendizaje

intercultural a través de su participación en el grupo de Facebook del

proyecto, asistiendo o siguiendo seminarios web de desarrollo profesional o

siendo miembros activos del proyecto. Dado que la participación en todos los

aspectos del proyecto era voluntaria, el número de participantes variaba, ya

que algunos participaban en varias actividades y otros sólo en una; además,

algunos adoptaban un papel de observadores que se limitaban a leer o ver,

mientras que otros adoptaban un papel más activo en el que dejaban comentarios,

hacían preguntas o participaban en las actividades. En vista de este diseño, sólo

fue posible identificar y analizar el número de respuestas de los estudiantes,

y no el número total de participantes. El número de respuestas de los alumnos

analizados para los seminarios web de desarrollo profesional fue el siguiente

Seminario web 1 = 21, Seminario web 2 = 39 y Seminario web 3 = 71. En cuanto al

número de estudiantes que participaron en el proyecto real, esta investigación

se centra en un pequeño grupo de 12 estudiantes que se ofrecieron a

proporcionar reflexiones individuales relativas a su desarrollo de las TIC en

una página separada de Padlet™: https://bit.ly/3eRMuwl

No

fue posible identificar datos como el género o la edad de los participantes, ya

que los individuos sólo proporcionaron su nombre y el programa en el que

estudiaban.

2.4.

Análisis de datos

Se

empleó un enfoque temático principalmente inductivo para explorar una amplia

gama de respuestas abiertas que los estudiantes habían proporcionado en

relación con diferentes aspectos del proyecto (Cresswell & Plano, 2007;

Nowell et al., 2017). A continuación, se redujeron y clasificaron en temas

clave para el debate. A partir de los datos cualitativos publicados en línea

por los estudiantes, ambos investigadores utilizaron un análisis de marco

(Ritchie & Lewis, 2003) que incluía varias etapas: (i) ambas investigadoras

se familiarizaron con los datos a través de exploraciones repetidas de los

mensajes en línea; (ii) cada investigadora propuso temas clave y negoció tres

temas de orden superior para el marco de codificación: Competencia y confianza

en las TIC, conocimiento pedagógico de las TIC y de su aplicación o uso, y

(iii) estos temas de orden superior se utilizaron para codificar todos los

datos mediante una hoja de cálculo en línea que permitió a los investigadores

colaborar de forma asíncrona y sincrónica. Este fue un factor importante en el

estudio debido a que ambos

investigadores no trabajaban en la misma ubicación física. A partir de los

datos cualitativos y cuantitativos recopilados, los investigadores pudieron

analizar cómo la participación en el proyecto HOTW, a cualquier nivel, ayuda a

desarrollar la competencia y las habilidades en materia de TIC de los

estudiantes de magisterio para prepararlos para las prácticas y su futura carrera

docente.

3.

Resultados

3.1.

Participación en el proyecto

La

participación en el proyecto se llevó a cabo mediante la visualización de los seminarios

web de desarrollo profesional o la participación en las actividades de

colaboración del proyecto. Los seminarios web de desarrollo profesional que los

estudiantes podían ver en directo o en la grabación en una fecha posterior

eran:

·

Webinario

1: Oct de 2019 – Aprendizaje colaborativo mediante eTwinning y otras

herramientas en línea

·

Webinario

2: Ene de 2020 – Justicia social a través del aprendizaje intercultural

·

Webinario

3: Abr de 2020 – Aprender durante el confinamiento

Se

animó a los estudiantes a dejar sus comentarios en las páginas de Padlet del

seminario web para compartir su aprendizaje. La Tabla 1 ofrece un resumen del

número de estudiantes que asistieron al seminario web en directo, vieron la

grabación y dejaron una respuesta.

Tabla 1

Número de estudiantes que

vieron o comentaron los webinarios

|

Webinarios |

Reproducciones de

webinarios |

Respuestas |

||

|

Total |

En directo |

Grabación |

||

|

1 |

80 |

19 |

61 |

21 |

|

2 |

71 |

32 |

38 |

39 |

|

3 |

195 |

131 |

64 |

71 |

El

número de estudiantes que vieron los seminarios en línea (en vivo o grabados)

aumentó durante el período de confinamiento por COVID-19 en un 160%. Antes del

cierre, la media de asistencia a los seminarios web 1 y 2 era de unos 75

estudiantes, sin embargo, durante el cierre esta cifra aumentó a 195

estudiantes en abril de 2020.

Este aumento

es aún más prominente en el número de estudiantes que vieron la transmisión en

vivo en comparación con la grabación. Antes del cierre de COVID-19, más

estudiantes veían la grabación en comparación con la transmisión en vivo: sin

embargo, durante el cierre los comportamientos de visualización cambiaron y la

transmisión en vivo se convirtió en la opción preferida. Durante el

confinamiento se produjo un aumento del 424% en la visualización en directo. La

asistencia media a los seminarios web 1 y 2, que tuvieron lugar antes del

cierre, fue de unos 25 estudiantes, frente a los 131 del seminario web 3, que

tuvo lugar durante el cierre. Aunque ahora se prefiere la versión de

transmisión en directo, también hubo un aumento del 31% de los estudiantes que

vieron los seminarios web grabados (una media de 49 estudiantes antes del

cierre en comparación con 64 durante el cierre). En lo que respecta a los

comentarios de reflexión, una media de 30 estudiantes envió un comentario en

los seminarios web 1 y 2, con un aumento del 51% a 71 estudiantes durante el

confinamiento. A partir de las cifras de visualización y publicación

anteriores, se observa un claro aumento de la participación de los estudiantes

en los seminarios web durante el confinamiento.

En

cuanto a la participación en las actividades del proyecto, las siguientes

actividades estaban abiertas a la participación de los estudiantes, ya sea en

prácticas o individualmente:

·

Una

postal tradicional con un giro moderno que usaba códigos QR, medios digitales,

y plataformas en línea para dar la vida a las postales.

·

“Ted,

el nómada, enseña al mundo a cantar” que también usaba códigos QR, medios

digitales, blogs y herramientas comunicativas en línea.

·

Canciones

colaborativas y retos que usaban plataformas en línea, medios digitales,

herramientas de votación en línea y herramientas de exponer en línea.

·

El

grupo de discusión pequeño, compuesto de 12 estudiantes que subieron

comentarios específicos dirigidos a su formación TIC en las antedichas

actividades, sirve para el análisis de datos datos que se exploran a

continuación.

3.2.

Competencia y confianza TIC

La

mayoría de los estudiantes del grupo de discusión (75%, n-8) señalaron que su

competencia y/o confianza habían aumentado gracias a su participación en el

proyecto. Sus niveles de competencia variaron, y dos estudiantes señalaron un

bajo nivel de competencia. La alumna 1 (Dianne, nombre ficticio) lo atribuyó a

que se ponía muy nerviosa cuando asistía a los talleres de TIC en la

universidad debido al ritmo rápido y a que se sentía incompetente en

comparación con los demás (Tabla 2, Cita 1), mientras que la alumna 2 (Lisa,

nombre ficticio) tenía miedo a la tecnología, lo que le hacía ser reticente a

la hora de utilizarla para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje (Tabla 2, Cita 2). En

el extremo opuesto de la escala de competencias se encontraban dos estudiantes

que poseían un alto nivel de competencia debido a experiencias anteriores: uno

de ellos tenía conocimientos de informática, mientras que el otro tenía

confianza en la experimentación con las TIC.

Por

ejemplo, muchos estudiantes hablaron con entusiasmo de la valiosa experiencia

de aprender de profesores experimentados, y Steph dijo que no habría tenido

éxito sin este apoyo (Tabla 2, Cita 3). Tres estudiantes que asistieron a los

seminarios web también comentaron que su competencia y confianza habían

aumentado gracias al aprendizaje de profesores experimentados, haciendo

referencia específica al aprendizaje en línea y mixto, como narró Sarah (Tabla

2, Cita 4).

Otros

dos factores clave fueron el tiempo y la relevancia que se destacaron como

importantes, ambos directamente relacionados con los resultados de estar

encerrados. El tiempo ya no era un obstáculo para muchos estudiantes, como

comentaron Nikki y Dianne (Tabla 2, Citas 5-6), que ya no tenían que viajar una

cantidad considerable de tiempo a la Universidad cada día. Este tiempo

adicional también favoreció a los estudiantes que necesitaban tiempo para

desarrollar sus habilidades y competencias en materia de TIC, como por ejemplo

Dianne y Niamh (Tabla 2, Citas 7-8). El hecho de poder asistir a los seminarios

web en directo porque el tiempo ya no era un obstáculo, permitió a Amy (Tabla

2, Cita 9) ser una estudiante activa en lugar de una observadora.

El

confinamiento también puso de manifiesto la importancia que tiene para muchos

estudiantes que los profesores conozcan y comprendan cómo utilizar las

tecnologías digitales para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje, lo que dio lugar a

que los estudiantes vieran la importancia de centrarse en este aspecto de su

desarrollo profesional, como ilustran los comentarios de Amy, Nikki. Niamh

(Tabla 2, citas 10-12).

Dos

estudiantes, que inicialmente tenían un nivel de competencia muy bajo,

observaron un notable aumento de la confianza. Dianne informó de que ahora se

sentía segura para trabajar como voluntaria con otro profesor del proyecto para

impartir una clase en línea, mientras que Lisa creó actividades de aprendizaje

digital para su comunidad local que comparte en su reflexión (Tabla 2, Cita 13)

Tabla 2

Ejemplos de competencia y

confianza con la tecnología digital

|

Cita |

Pseudónimo |

Extractos de datos |

|

1 |

Dianne |

''...teniendo vergüenza cuando

no sabía qué hacer. Los otros podían seguir las instrucciones y hacer cosas y

yo siempre necesitaba ayuda.' |

|

2 |

Lisa |

'... temiendo enseñar o usar

TIC con los niños.' |

|

3 |

Steph |

'No habría podido hacer esto

sin la dirección y el apoyo que me dio mi profesor HOTW.' |

|

4 |

Sarah |

‘El aprendizaje

híbrido ha sido una preocupación para mí…Este webinario era muy informativo y

ha hecho más fácil mis inquietudes sobre enseñar en línea y usar tecnología.’

|

|

5 |

Nikki |

'¿Habría podido hacer esto

si hubiera estado viajando durante 90 minutos cada trayecto a la universidad

cada día? Creo que no, entonces, gracias al confinamiento, el tiempo se me

regalaba.' |

|

6 |

Dianne |

'Debido a estar en el

confinamiento, tuve mucho tiempo extra porque dejé de tener que viajar tres

horas hacia y desde la universidad.' |

|

7 |

Dianne |

'Pasé las semanas siguientes

viendo otra vez el webinario grabado y probando tecnología que me parecía

interesante.' |

|

8 |

Niamh |

'...durante el confinamiento

tenía una familia joven en mi casa y era mucho más fácil hacer muchas

actividades pequeñas de aprendizaje en vez de tener que dedicar unas horas.' |

|

9 |

Amy |

'’Me di cuenta de que

asistir a los webinarios en directo era mucho más interesante porque pude

dirigir preguntas a los profesores en vez de sólo ver las exposiciones.

Después pude probar muchas de las herramientas TIC que se mostraron debido al

hecho de tener el tiempo para hacerlo – ¡los beneficios del confinamiento!' |

|

10 |

Amy |

‘Gracias por las

oportunidades para darme la confianza para querer usar la tecnología cuando

sea profesora, especialmente en un mundo en que necesitamos usarlo más que

antes.' |

|

11 |

Nikki |

‘El confinamiento hizo que

aprendizaje en línea sea un factor importante en la educación, quería

aprender lo más posible.' |

|

12 |

Niamh |

‘Sentía que la

pandemia me había abierto los ojos sobre la importancia de usar TIC para

enseñar los niños en línea y cuando finalmente hayan regresado al aula.' |

|

13 |

Lisa |

‘Empecé a tener más

confianza cuando creé una búsqueda QR en mi área local para que los niños

locales resolvieran un problema de palabras. En el problema-reto usé muchas

de las herramientas que había aprendido durante el proyecto, por ejemplo,

mentimeter, padlet, SWAY y Google Forms.' |

3.3. Conocimiento

pedagógico de TIC

Aunque

había estudiantes que eran usuarios de las TIC competentes, reconocían que no tenían

conocimientos pedagógicos de las mismas. Nikki, por ejemplo, que tenía cierto

conocimiento de las aplicaciones educativas debido a que tenía una familia

joven, no tenía conocimiento de cómo utilizar las herramientas digitales

pedagógicamente. Del mismo modo, Peter y Louise tenían conocimientos sobre el

uso de las TIC, pero no dentro de un contexto educativo, tal y como expresó

Louise (Tabla 3, Cita 1).

Los

estudiantes hablaron positivamente sobre el desarrollo de su pedagogía de las

TIC a través de la participación en el proyecto y de cómo podían utilizar la

tecnología digital de forma creativa, colaborativa, inclusiva e innovadora,

como compartieron Mark, Louise, Peter, Nikki y Hope (Tabla 3, Citas 2-6).

Los

estudiantes identificaron el aprendizaje de otros en el grupo de Facebook de la

comunidad de práctica activa del proyecto como una característica clave en su

desarrollo. Algunos estudiantes, como Gillian, Mark y Peter (Tabla 3, Citas

7-9), aprendieron a través de la observación, y otros a través de preguntas,

como describe Lisa (Tabla 3, Cita 10).

Tabla 3

Ejemplos de conocimiento

pedagógico de TIC

|

Cita |

Pseudónimo |

Extractos

de datos |

|

1 |

Louise |

‘Aunque tengo un nivel

alto de experiencia de uso de la tecnología, no conozco todas las

aplicaciones que se pueden usar con niños y no tengo el conocimiento de

enseñanza que se necesita para poder usar las tecnologías eficazmente.’ |

|

2 |

Mark |

‘Uno de los aspectos

claves que saqué del Proyecto, fue el uso creativo de TIC y para permitir a

los niños conectar entre sí de maneras diferentes.’ |

|

3 |

Louise |

‘Mi momento favorito

de aprendizaje fue cuando vi los códigos QR dar la vida a los postales…Que

manera tan maravillosa de usar una parte tan simple de la tecnología.' |

|

4 |

Nikki |

'Antes del Proyecto HOTW no

sabía cómo usar la tecnología para trabajo colaborativo, respuestas

colaborativas, compartir aprendizaje en línea, gestionar espacios en línea, usar

herramientas como código QR, usar blogs con niños, creación de contenido por

herramientas multimedios.’ |

|

5 |

Peter |

'He visto códigos QR

en muchas cosas, no obstante, nunca había considerado usarlos para dar la

vida al aprendizaje y para crear una educación inclusiva.' |

|

6 |

Hope |

‘A continuación pude

aprender a saber usar muchas herramientas TIC de las que antes nunca había

escuchado hablar, por ejemplo, nunca había pensado en usar los códigos QR en

la educación…Ver los postales cobrar vida con el código QR era una idea

increíble. Que maravilloso tipo de tecnología simple e inclusivo.’ |

|

7 |

Gillian |

'También aprendí

mucho al formar parte del grupo de Facebook (FB) de HOTW dónde aprendí al

comprobar con la lectura de las publicaciones de los profesores que ellos

buscaron ayuda sobre el uso de la tecnología. Esto me hizo sentir mucho mejor

en el aspecto que no tengo que saber todo sobre TIC cuando llegue a ser

profesora.’ |

|

8 |

Mark |

'El grupo de Facebook

era muy útil… Durante el confinamiento al principio, lo encontraba muy

interesante porque todos los profesores estaban buscando maneras de trabajar

en línea… Siento que aprendí tanto en el grupo de Facebook como en los

webinarios.' |

|

9 |

Peter |

‘¡Es increíble lo que

podrías aprender incluso solo al leer las publicaciones de otros profesores!’ |

|

10 |

Lisa |

'Así es cómo me ayudó

el grupo de Facebook, al poder subir preguntas para pedir ayuda e

inmediatamente los profesores en el proyecto o los estudiantes de magisterio

me respondieron para dar consejos.' |

Los seminarios

web de desarrollo profesional también contribuyeron a la formación de para el

desarrollo de la pedagogía de las TIC. Los comentarios realizados en el

seminario web 1 estaban relacionados con las herramientas en línea y/o de

colaboración (6 respuestas), mientras que en el seminario web 3 hubo más de 60

respuestas relacionadas con las herramientas en línea, y los estudiantes (n-22)

mencionaron el término "aprendizaje mixto presencial-virtual". Los

estudiantes también se refirieron a varias herramientas digitales que les

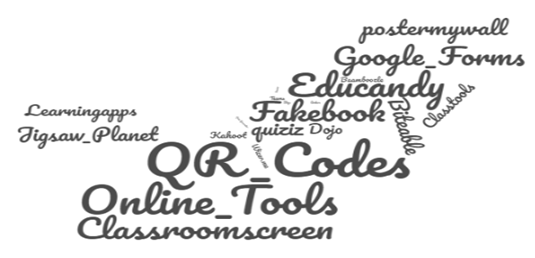

parecieron interesantes o que deseaban explorar más. Las principales

herramientas digitales a las que se refirieron los estudiantes se muestran en

la Figura 1, donde las herramientas en línea y los códigos QR fueron los más

populares. Por el lenguaje utilizado, por ejemplo: útil, perspicaz, provechoso,

interesante e informativo, quedó claro que los estudiantes sacaron mucho

provecho de los seminarios web, especialmente del seminario web 3, que se

centró en el aprendizaje en línea.

Figura 1

La tecnología mencionada

por los estudiantes después de los webinarios

3.4.

Aplicación de TIC

Los

estudiantes aplicaron lo que habían aprendido en diferentes contextos: en las

prácticas, en casa (individualmente o con otros) o en línea (con una escuela

del proyecto), y muchos vieron conexiones con la práctica futura. Un

estudiante, Peter, consiguió participar en el proyecto de las postales (uno de

los muchos proyectos disponibles) con su clase de prácticas, donde tuvo una

rica experiencia de aprendizaje debido a que dirigió el proyecto, compartió sus

habilidades en TIC con su mentor y vio las reacciones positivas de los niños

(Tabla 4: Cita 1). La mayoría de los estudiantes no pudieron participar en el

proyecto con una clase debido al cierre, sin embargo, como el proyecto seguía

funcionando en línea, los estudiantes tuvieron la oportunidad de trabajar con

profesores y clases de todo el mundo. La narración de Steph y Gillian sobre su

experiencia de aprendizaje ejemplifica la valiosa experiencia que tuvieron

estos estudiantes, que pudieron adquirir experiencia en la enseñanza en línea

con el apoyo de un profesor experimentado que conocía la clase y la tecnología

que se adaptaba a sus necesidades (Tabla 4, Citas 2-3). Otros estudiantes, que

tenían familiares en casa, realizaron algunas de las actividades con ellos.

Esta fue una interesante actividad de aprendizaje social para Sarah (Tabla 4,

Cita 4), en la que varias personas se beneficiaron de que Sarah trabajara con

su hermano menor. Del mismo modo, Amy aprendió ella sola a hacer películas en

colaboración y luego enseñó a sus hijos a hacerlas.

La

mayoría de los estudiantes del grupo de discusión afirmaron que estaban

deseando utilizar la tecnología digital y/o formar parte del proyecto con su

próxima clase. Del mismo modo, los que asistieron a los seminarios web, también

se refirieron a lo útiles que fueron los seminarios web para la práctica

futura, afirmando que ahora se sentían más preparados y seguros para integrar

las TIC en su práctica profesional, ya sea en el aula o en línea (Tabla 4, Cita

5).

Tabla 4

Ejemplos de la aplicación

de TIC

|

Cita |

Pseudónimo |

Extractos de datos |

|

1 |

Peter |

'A ellos les encantaba usar

todas las tecnologías diferentes y conectarse con otros colegios alrededor

del mundo ¡Incluso logramos conectarnos en directo con una de las clases, que

fue algo nuevo para ellos cuando Zoom no estaba de moda! Después de algunos

problemas técnicos, logré encontrar cómo conectar los alumnos, que impresionó

mucho al profesor de la clase.’ |

|

2 |

Steph |

'Cuando surgió la

oportunidad para poder trabajar con una profesora y su clase para enseñar una

actividad a la clase, estaba muy emocionada porque ahora pude experimentar el

confinamiento mientras enseñaba… Esta experiencia ha quedado conmigo como una

de las más valiosas que tuve durante el confinamiento y me ha impulsado a

formar parte de este proyecto con mi clase para que podamos trabajar en

colaboración con otros de forma interesante.' |

|

3 |

Gillian |

Esto fue una experiencia de

aprendizaje valiosa ya que pude trabajar con la profesora de la clase y conocer

las tecnologías adecuadas para la sesión que quise enseñar…Ella también me

indicó las barreras que un alumno posiblemente podría encontrar durante una

sesión de clase mientras utilizar un tipo específico de tecnología, por lo

tanto, me recordó la exclusión digital en casa y cómo se puede lograr que el

aprendizaje digital fuera inclusivo.' |

|

4 |

Sarah |

'Probé muchas de las

actividades con mi hermano menor. Vi los webinarios y después mi hermano me

ayudó a probar algunas de las herramientas diferentes y pudo explicar si las

había empleado y cómo las había usado. Le gustaba Google Forms y creó

cuestionarios para sus compañeros y los vio con su profesora. Ahora ella

usaba Google Forms con la clase de mi hermano, algo que es muy interesante

porque todos estaban aprendiendo juntos.' |

|

5 |

Hope |

‘Siento como esto es

una de las habilidades TIC más valiosas que aprendí durante el proyecto, que

podré las podré usar como una profesora y en mi vida personal. Desde el

primer confinamiento en marzo, he visto muchos videos en línea que contienen

muchas personas de lugares diferentes.’ |

4. Discusión

y conclusión