Competencia

digital docente en educación de adultos: un estudio en un contexto español

Digital competence in adult education: a study in a Spanish

context

Dña. Esther Garzón Artacho. Estudiante de Doctorado. Facultad

de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dña. Esther Garzón Artacho. Estudiante de Doctorado. Facultad

de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dr. Tomás Sola Martínez. Catedrático de Universidad. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dr. Tomás Sola Martínez. Catedrático de Universidad. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dr. Juan Manuel Trujillo Torres. Profesor Titular de Universidad. Facultad de Ciencias

de la Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dr. Juan Manuel Trujillo Torres. Profesor Titular de Universidad. Facultad de Ciencias

de la Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dr. Antonio Manuel Rodríguez García. Profesor Ayudante Doctor. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dr. Antonio Manuel Rodríguez García. Profesor Ayudante Doctor. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Recibido:

2021/01/15 Revisado: 2021/02/18 Aceptado: 2021/07/06 Preprint: 2021/07/19 Publicado: 2021/09/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Garzón-Artacho, E.,

Sola-Martínez, T., Trujillo-Torres, J.M., & Rodríguez García, A.M. (2021).

Competencia digital docente en educación de adultos: un estudio en un contexto

español [Digital competence in adult

education: a study in a Spanish context]. Pixel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, 62, 209-234. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.89510

RESUMEN

La competencia digital es una de las siete

competencias clave para el aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida. Más

específicamente, la competencia digital docente abarca el conjunto de

conocimientos, habilidades, destrezas, capacidades y actitudes relacionadas con

el uso crítico y creativo de las tecnologías aplicadas a los contextos

educativos para maximizar el éxito de los procesos de

enseñanza-aprendizaje.Esta investigación tiene por objetivo estudiar la

competencia digital docente de una muestra de profesores de educación de

adultos en un contexto español. Para ello, se ha llevado a cabo un estudio

trasversal, cuantitativo y descriptivo con una muestra de 140 profesores de

Andalucía (España). Los análisis estadísticos realizados

(descriptivo-inferencial) determinan que el nivel de competencia se sitúa en

torno a niveles intermedios, especialmente en lo que respecta a las habilidades

para comunicarse y colaborar con los demás; y bajos en el resto de áreas

competenciales, especialmente en lo que se refiere a la resolución de problemas

técnicos. De igual modo, se comprueba que la categoría profesional, la

formación previa en TIC, el nivel de estudios y la edad son variables que

influyen en el mayor o menor desarrollo de la competencia digital docente.

ABSTRACT

Digital competence is one of the seven key competences

for lifelong learning. More specifically, teaching digital competence covers

the set of knowledge, skills, abilities, capacities and attitudes related to

the critical and creative use of technologies applied to educational contexts

in order to optimise the success of teaching-learning processes.This research

aims to study the digital teaching competence of a sample of adult education

teachers in a Spanish context. To this end, a cross-sectional, quantitative and

descriptive study was carried out with a sample of 140 teachers from Andalusia

(Spain). The statistical analyses carried (descriptive-inferential) out

determine that the level of competence is around intermediate levels,

especially with regard to skills for communicating and collaborating with

others; and low in the remaining areas of competence, especially with regard to

the resolution of technical problems. Similarly, the professional category,

previous ICT training, level of studies and age are variables that influence

the greater or lesser development of digital teaching competence.

PALABRAS CLAVES · KEYWORDS

Competencia digital,

docentes, educación de adultos, educación permanente, TIC

Digital competence, teachers,

adult education, lifelong learning, ICT

1.

Introducción

La sociedad actual se caracteriza por estar en

continuo movimiento. Nos encontramos ante un período de transformaciones

económicas, políticas y sociales que suceden con gran celeridad, más

especialmente tras la metamorfosis radical que ha experimentado la sociedad en

general, y el sistema educativo en particular, durante los últimos años

(Cabero-Almenara & Llorente-Cejudo, 2020; Blaschke, 2021; Cabero-Almenara

& Valencia, 2021). En este contexto versátil y complejo surgen nuevas

maneras de relacionarse y comunicarse con los demás y, por ende, nuevas

tendencias y entramados de liderazgo que guían el desarrollo de las nuevas

sociedades, las cuales son cada vez más exigentes y competitivas.

El yacimiento de nuevos entornos educativos que rompen

con el paradigma tradicional de enseñanza-aprendizaje (Hinojo-Lucena et al.,

2019; Serafín et al., 2019); la recualificación de las competencias ciudadanas

para un entorno sociolaboral en continua transformación (Brown et al., 2020);

la amplitud o crecimiento de los mercados empresariales y la economía global

(Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019); así como el continuo avance de la tecnología

digital precisa de personas que tengan un alto nivel de competencia digital

(Gutiérrez & Cabero, 2016; Rodríguez-García et al., 2017; Rodríguez-García

et al., 2019a). Esta situación ha quedado aún más manifiesta a raíz de los

tiempos que hemos vivido en los años 2019-2020, donde todo el entramado

educativo (profesores y alumnos de todos los niveles) tuvieron que pasar de una

enseñanza totalmente presencial a otra totalmente virtual de manera urgente

(Cabero-Almenara & Valencia, 2021; Martínez-Garcés & Garcés-Fuenmayor,

2020). Nos encontramos, como ya

mencionaron Arranz et al. (2017) y Elayyan (2021), ante una posible cuarta

revolución industrial debido a la inminente evolución del Internet de las

cosas, la robótica o la inteligencia artificial, entre otros.No cabe duda que

la competencia digital es necesaria en la actualidad (Cappuccio et al., 2016;

Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2021; Rolf et al., 2019). De hecho, la Comisión Europea

la cataloga como estrictamente ineludible para ser un miembro activo,

participativo e incluido en la sociedad, así como requisito para facilitar el

aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida (Halász & Michel, 2011; Shonfeld et al.,

2021). En líneas generales, la competencia digital hace referencia al conjunto

de habilidades, destrezas y actitudes que facilitan la interrelación

bidireccional y segura con el mundo digital, con sus dispositivos, aplicaciones

de comunicación, redes y páginas de acceso a información (Cabero-Almenara et

al., 2020; Rodríguez-García et al., 2019b). A su vez, todas estas destrezas nos

permiten crear, editar y modificar contenidos digitales, compartirlos con otras

personas y colaborar con ellas. Y, al mismo tiempo, nos facilita otorgar

solución a los problemas con el objetivo de lograr un desarrollo eficaz y

creativo en la vida, el trabajo y la sociedad (Guitert et al., 2021).

El conjunto de habilidades y destrezas que las

empresas y la sociedad en sí demandan han ido evolucionando para posicionar a

la competencia digital como una serie de destrezas esenciales en su desarrollo

para relacionarse de manera eficaz en la sociedad del siglo XXI (Hatlevik &

Christophersen, 2013). Así, los gobiernos han de comprender estas nuevas

demandas y adaptar el sistema a las nuevas necesidades. De hecho, algunos

autores han señalado la importancia de conocer habilidades avanzadas

relacionadas con la competencia digital (inteligencia artificial, big data, machine learning…) para así

mejorar la empleabilidad en el futuro y ser alternativas efectivas a los

trabajos que tenderán a desaparecer (Arranz et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2020;

Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019). Y, por consiguiente, sería necesario llevar a

cabo políticas de reorientación profesional para aquellas poblaciones que

corren el riesgo de una descalificación de sus empleos.

No cabe duda que la digitalización es un fenómeno

imparable y, por ende, la competencia digital del ciudadano debe ser adecuada a

estos tiempos. A pesar de su importancia, encontramos desigualdades en torno a

la edad, género, estatus socioeconómico, raza, formación, geografía, entre

otras (Mariscal et al., 2019). En este sentido, algunas de estas variables

pueden convertirse en factores de riesgo que puedan distanciar a estos

colectivos de una inclusión digital plena y, por tanto, ser excluidos de un

sistema que no los quiere por no tener un buen dominio de conocimientos

tecnológicos (Kalolo, 2019). Sin embargo, la brecha de conocimiento en cuanto a

las destrezas digitales puede paliarse a través de la formación (Allmendinger

et al., 2019).

La formación se ha convertido en una línea de

actuación prioritaria por parte de organizaciones nacionales e internacionales,

cuyas políticas se centran en proporcionar un mayor acceso a la tecnología,

disminuir las desigualdades sociales y fomentar un mayor conocimiento y

adquisición de habilidades digitales (Rosi & Barajas, 2018). De ello se

deriva, a su vez, la importancia que ha recibido actualmente el estudio de la

competencia digital docente, como agente de referencia, (Johannesen et al.,

2014; Cappuccio et al., 2016; Ilina et

al., 2019; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2020; ) y la sucesión de investigaciones que

tratan de averiguar el nivel de destreza de estos en las distintas etapas

educativas (Guitert et al., 2020; Lucas et al., 2021).

El aprendizaje permanente es, pues, un objetivo

prioritario y es una respuesta para aminorar las desigualdades que presenta la

sociedad (Blaschke, 2021). En España, el aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida va

más allá de un mero enfoque de educación de adultos. Se hace hincapié en la

importancia de preparar al alumnado para que este pueda aprender por sí mismo y

adaptarse a las demandas cambiantes de la sociedad del conocimiento,

facilitando tanto su desarrollo personal como profesional. Por tanto, es

importante cuestionarse sobre el nivel de competencia digital de los docentes

de educación de adultos, como agentes de referencia para sus alumnos

(Allmendinger et al., 2019).

2.

Metodología

Una vez asentadas las bases conceptuales que preceden

al marco empírico del estudio que aquí presentamos, la presente investigación

se encuadra dentro de una metodología de naturaleza cuantitativa, de carácter

no experimental y trasversal con una idiosincrasia descriptiva (Hernández et

al., 2016) a fin de aproximarnos al nivel competencial de los docentes de

educación de adultos, así como comprobar si hay factores que pueden incidir en

su desarrollo (Capuccio et al., 2016; Gudmundsdottir

& Hatlevik, 2018; Serafín et al., 2019), conociendo así sus percepciones y

valoraciones.

2.1.

Objetivos específicos

Operativamente, el presente trabajo tiene como

finalidad conseguir los siguientes objetivos:

1.

Analizar el nivel de competencia digital del

profesorado de educación de adultos en Andalucía.

2.

Determinar si existen diferencias significativas entre

cada nivel de las distintas variables independientes, en relación a las

variables dependientes.

3.

Determinar el porcentaje en el que la hipótesis nula

se rechaza a favor de la hipótesis alternativa, y concretar los sujetos mínimos

para hallar significación estadística.

2.2.

Participantes y contexto

La muestra participante en este estudio está conformada

por docentes de Educación Permanente de los centros públicos de la región de

Andalucía, España (N = 140). Para la obtención de la mismase llevó a cabo un

muestreo aleatorio estratificado teniendo en consideración las diferentes

provincias de Andalucía (Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Granada, Huelva y Sevilla) y

las tres principales tipologías de centros de educación de adultos: Centros de

Educación Permanente (CEPER) y Secciones de Educación Permanente (SEPER) e

Institutos de Educación Secundaria con enseñanzas para personas adultas (IES).

El resto de datos sociodemográficos (edad, formación previa en TIC, titulación,

experiencia profesional, entre otros) se muestran en la Tabla 1.

Datos

sociodemográficos

|

Datos sociodemográficos |

N |

M(SD) or % |

|

|

Región |

|

|

|

|

Almería |

28 |

20 |

|

|

Cádiz |

16 |

11.43 |

|

|

Córdoba |

17 |

12.15 |

|

|

Granada |

49 |

35 |

|

|

Huelva |

15 |

10.71 |

|

|

Sevilla |

15 |

10.71 |

|

|

Centro |

|

|

|

|

CEPER and SEPER |

97 |

69.28 |

|

|

IES |

43 |

30.72 |

|

|

Edad |

140 |

35.4(8.56) |

|

|

Género |

|

|

|

|

Masculino |

66 |

47.14 |

|

|

Femenino |

74 |

52.86 |

|

|

Formación previa en TIC |

|

|

|

|

Si |

100 |

71.42 |

|

|

No |

40 |

28.58 |

|

|

Estudios |

|

|

|

|

Diplomatura |

83 |

59.28 |

|

|

Licenciatura |

41 |

29.29 |

|

|

Master |

16 |

11.43 |

|

|

Experiencia docente |

140 |

4.98(3.06) |

|

|

Categoría profesional |

|

|

|

|

Funcionario |

88 |

62.85 |

|

|

Interino |

52 |

37.15 |

|

2.3.

Instrumento

Los datos fueron recogidos

de manera trasversal durante el curso académico 2019-2020, a partir de la

aplicación de un cuestionario online sobre competencia digital. El cuestionario

se compuso por 91 ítems, divididos en las cinco áreas de la competencia digital

docente del INTEF (2017). Los ítems se basaron en cada uno de los indicadores

que componen cada una de las cinco áreas: 16 indicadores de información y

alfabetización informacional; 31 de comunicación y colaboración; 16 de creación

de contenido digital; 13 de seguridad; y 15 de resolución de problemas. Para la

validación de instrumento, se empleó un Análisis Factorial Exploratorio (con

rotación varimax y con Minimum

residual). Los resultados destacaron que 5 dimensiones son suficientes para

retener los datos. El cuadrado medio de los residuos (RMSR) de la raíz fue de

0,05. Esto es aceptable ya que este valor debe estar más cerca de 0. A

continuación, se comprobó el RMSEA (raíz de error cuadrado medio de

aproximación). Su valor, .0001, muestra buen modelo de ajuste ya que está por

debajo de 0,05. Por último, el índice de Tucker-Lewis (TLI) es 0,93-un valor

aceptable- teniendo en cuenta que es más de 0,9; un Análisis de Componente

Principales (se realizó una PCA ya que todas las variables dependientes del

estudio son métricas y los resultados destacan que diez dimensiones serían la

opción óptima); además del criterio de Kaiser-Guttman.

Las respuestas a cada ítem

se recogieron en una escala Likert de 10 niveles (1 = never;

10 = always). El análisis de fiabilidad del

instrumento recogió un valor aceptable en el coeficiente alfa de Cronbach

(α =.93). Se usó la Prueba de Wilcoxon para muestras relacionadas, pues

compara las medianas de dos muestras relacionadas para determinar si existen o

no diferencias entre ellas. Es la versión no paramétrica del t-test para

muestras dependientes. Su función fue la siguiente: wilcox.test

(x, y, paired = TRUE, alternative

= “greater”). La primera prueba estadística determina

que, en cuanto al género, no existieron diferencias estadísticamente

significativas entre hombres y mujeres en ninguna variable dependiente. Esto se debe a que

el p-value = 0,07953, luego:

alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not greater tan

0.

2.4.

Análisis de datos

El análisis de los datos

obtenidos se llevó a cabo a través del lenguaje de programación RStudio. Esta investigación presenta un diseño ANCOVA, en

el que se emplearon técnicas de análisis descriptivo (tales como media,

desviación típica, …) e inferencial (prueba U de Mann-Whitney y de

Kruskal-Wallis). En primer lugar, The Wilcoxon rank-sum test es un test no paramétrico cuyo objetivo es

contrastar si dos muestras proceden de poblaciones equidistribuidas.

Por otro lado, la prueba de Kruskal-Wallis complementa la anterior para 3 o más

grupos.

Para realizar estas

operaciones se tuvieron en cuenta 8 variables independientes, siendo dos de

ellas variables métricas, y 21 variables dependientes agrupadas en cinco grupos

(Tabla 2).

3.

Análisis y resultados

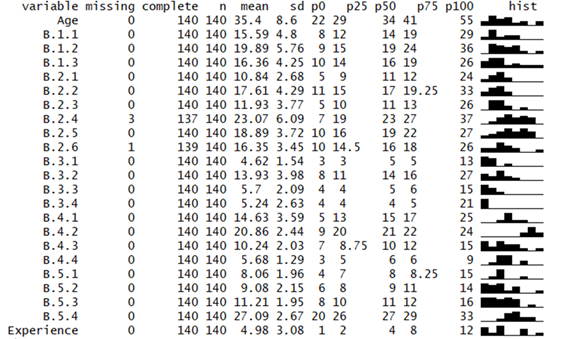

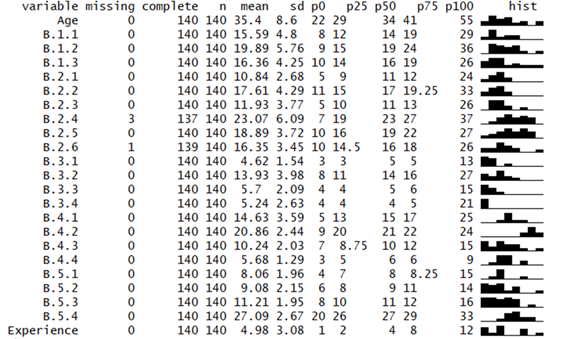

Atendiendo a nuestro primer

objetivo, el análisis descriptivo efectuado para cada una de las variables

independientes (Figura 1) muestra que las dimensiones con mayores puntuaciones

medias fueron B.5.4 (identificación de lagunas en la competencia digital) y

B.2.4. (colaboración mediante canales digitales). En este sentido, para

corregir los valores perdidos, se imputaron por la media. Por el contrario, las

dimensiones con menores puntuaciones medias fueron B.3.1 (desarrollo de

contenidos digitales), B.3.4 (programación) y B.3.3 (aplicación y conocimiento

de derechos de autor y licencias).

Figura 1

Estadística descriptiva para las variables de la investigación

Tabla 2

Variables de investigación

|

Variables independientes |

Variables dependientes |

|

Centro: CEPER (0) SEPER (1) IES (2) Edad Sexo Hombre (0) Mujer (1) Formación previa en TIC

(TIC.For) Si (0) No (1) Estudios (Degree) Diplomatura (0) Licenciatura (1) Máster (2) Experiencia docente

(Experience) Categoría profesional

(Prof.Cat) Funcionario (1) Interino (2) |

B.1-Información y alfabetización

informacional B.1.1. Navegación,

búsqueda y filtrado de información B.1.2. Evaluación

de la información, datos y contenidos digitales B.1.3.

Almacenamiento y recuperación de información, datos y contenidos digitales B.2-Comunicación y

colaboración B.2.1. Interacción

mediante las tecnologías digitales B.2.2. Compartir

información y contenidos digitales B.2.3. Participación

ciudadana en línea B.2.4. Colaboración

mediante canales digitales B.2.5. Netiqueta B.2.6. Gestión de la

identidad digital B.3-Creación de

contenidos digitales. B.3.1. Desarrollo de

contenidos digitales B.3.2. Integración y

reelaboración de contenidos digitales B.3.3. Derechos de autor y

licencias B.3.4. Programación B.4-Seguridad B.4.1. Protección de dispositivos B.4.2. Protección de datos

personales e identidad digital B.4.3. Protección de la

salud B.4.4. Protección del

entorno B.5-Resolución de

problemas B.5.1. Resolución de

problemas técnicos B.5.2. Identificación de

necesidades y respuestas tecnológicas B.5.3. Innovación y uso de

la tecnología digital de forma creativa |

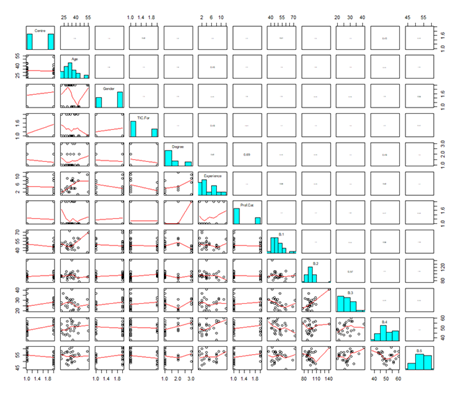

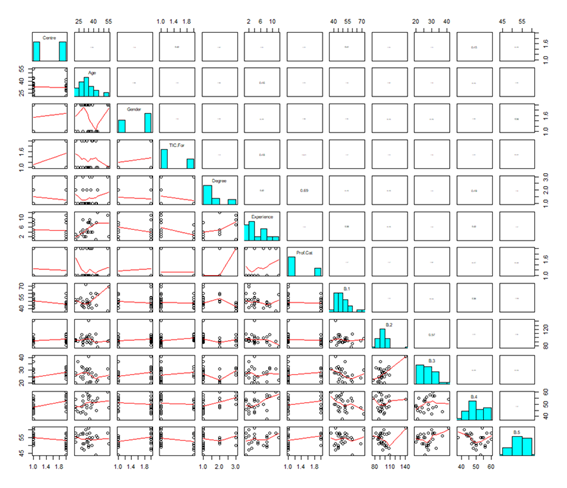

En cuanto al análisis de normalidad y linealidad de las

variables que componen el estudio, y por un interés investigador, se agruparon

el conjunto de las variables dependientes en torno a sus cinco dimensiones

(B1-B5). En este sentido, debido a que los datos no cumplieron los supuestos de

normalidad multivariada (p<.05), pero sí el de homogeneidad de

varianza-covarianza (p>.05) (véase Figura 2) se emplearon pruebas no

paramétricas (no se cumple el criterio de normalidad ni el de homocedasticidad

de la varianza-covarianza).

Figura 2

Normalidad y linealidad entre las distintas

variables del estudio

No

fue necesario emplear pruebas robustas debido a que los outliers

fueron recortados (imputados) por la mediana.

Las

pruebas estadísticas empleadas para determinar si existen diferencias

significativas entre los distintos niveles de las variables independientes

fueron el test de Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon (WMW) y prueba de Kruskal-Wallis para

poblaciones de tres o más grupos. La primera prueba estadística determina que,

en cuanto al género, no existieron diferencias estadísticamente significativas

entre hombres y mujeres en ninguna variable dependiente.

No

obstante, en cuanto a la categoría profesional (Prof.Cat)

se hallaron diferentes significativas en la variable dependiente B.3 (W = 189,

p-value =.04944) y B.5 (W = 159.5, p-value = .01008). De igual modo, en cuanto a la variable

independiente formación previa en TIC (TIC.For),

encontramos diferencias significativas entre los participantes para B.3 (W =

1559, p-value = .001628) y B.5 (W = 1810, p-value = .03871).

La

aplicación de la prueba de Kruskal-Wallis en la variable independiente centros,

determina que existen diferencias significativas entre todos los centros

educativos (X2(X) = Y; p < .01). Para determinar entre qué grupos y cuánta

diferencia existió se emplearon comparaciones múltiples post hoc de Nemenyi y Tukey:

·

B.1

(Centro 2 y Centro 1)

·

B.2

(Centro 2 y Centro 0; Centro 2 y Centro 1)

·

B.3

(Centro 2 y Centro 0; Centro 2 y Centro 1)

·

B.4

(Centro 0 y Centro 1; Centro 0 y Centro 2)

·

B.5

(Centro 2 y Centro 0; Centro 2 y Centro 1)

En

relación a la edad, sólo existieron diferencias significativas entre las distintas

edades para B.1 (X2(24) = 23.5, p < .05) y B.2 (X2(24) = 23.5, p < .05).

Respecto a la titulación, hallamos diferencias significativas en B.1 (X2(2) =

7.3 p < .01), más concretamente entre Titulación 2 y Titulación 1.

En

cuanto a la experiencia docente, no existieron diferencias significativas

univariantes en función de esta variable independiente. Sin embargo, esto no

sucedió desde un punto de vista multivariante (ANOSIM) (p=.04; R2=.43).

Finalmente,

dando respuesta a nuestro objetivo específico tercero, en términos estadísticos

la potencia de un contraste corresponde a la probabilidad de rechazar la

hipótesis nula. La potencia de la prueba fue de .9 (power

= .9004524). Esto significa que la H0 será rechazada en favor de la H1 en el

90% de los casos. Para detectar efectos, se requieren 26 sujetos (n =

26.13751).

4.

Discusión

El presente estudio ofrece información sobre el grado

de competencia digital docente del profesorado de educación de adultos de la

comunidad autónoma de Andalucía (España), explora el nivel de competencia

digital de los mismos e investiga acerca de las posibles variables que pueden

incidir en presentar un mayor o menor nivel de cualificación al respecto, tales

como la edad, el contexto, la situación profesional, el nivel de estudios,

entre otros.

En relación al primer objetivo, los análisis

estadísticos realizados determinan que el nivel de competencia digital docente

se sitúa en torno a niveles intermedios, especialmente en lo que respecta a las

habilidades para comunicarse y colaborar con los demás; y bajos en el resto de

áreas competenciales, especialmente en lo que se refiere a la resolución de

problemas técnicos. Esta situación parece reproducirse en varias

investigaciones, independientemente de que la muestra analizada sea de educación

primaria, secundaria, universidad o de educación de adultos, tal y como

muestran los trabajos de Cabero-Almenara et al. (2020), Casal et al. (2021),

Colás-Bravo et al. (2019) y Moreno-Guerrero et al. (2021).

Los profesionales de la educación actuales parecen

tener más destrezas para comunicarse con otras personas, así como para realizar

propuestas de trabajo colaborativo con otras personas en detrimento de su

alfabetización informacional, es decir, de sus destrezas para hallar

información válida, importante y pertinente, así como para crear contenidos

digitales, salvaguardar su seguridad en la interacción con la red y resolver

problemas técnicos cuando las tecnologías no funcionan correctamente. Así pues,

en este trabajo se constata, al igual que en estudios precedentes

(Rodríguez-García et al., 2019a; Pozo-Sánchez et al., 2020; Casal et al., 2021)

que la competencia digital continua siendo una meta que no termina por

completarse, continuando siendo un reto para el mundo de la educación actual

(Rodríguez-García et al., 2019b). A pesar de este hecho, la muestra analizada

afirma estar capacitada para identificar déficits formativos en su competencia

digital, por lo que pueden fortalecer aquellos aspectos donde existen mayores

carencias de aprendizajes. Aquí adquiere un papel importante la formación

continua del docente, siendo este un aspecto clave para la adaptación a las

necesidades que la sociedad actual va demandando a los distintos profesionales

de cualquier sector productivo (Brown et al., 2020).

Por otro lado, en relación al segundo objetivo, es

decir, respecto a los análisis realizados para comprobar si determinadas

variables tienen influencia en el desarrollo de la competencia digital, cabe

señalar que no se encontraron datos significativos respecto al género, a

diferencia de otros estudios que señalan que los hombres tienden a utilizar más

la tecnología y, por tanto, su competencia digital es superior (Mariscal et

al., 2019; Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2019;Serafín et al.,2019; Del Prete & Cabero,

2020). Sin embargo, la investigación de Pozo et al. (2020) señala que las

mujeres disponen de un mayor nivel de competencia digital en la dimensión de

creación de contenidos digitales, teniendo estas más predisposición al uso

pedagógico de los mismos.

Por otro lado, cabe destacar que la categoría

profesional (funcionario o interino), así como la formación previa en TIC

influyen en dos áreas de la competencia digital: creación de contenidos

digitales (B.3) y en la resolución de problemas (B.5). Ello puede ser debido a,

tal y como mencionan Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik (2018) en su investigación,

a la escasa cualificación de los docentes en competencia digital. De igual

modo, se observan diferencias significativas respecto al centro de trabajo en

todas las dimensiones de la competencia digital. De este modo, el contexto es

fundamental y una variable que influye en el desarrollo de la competencia

digital (Hatlevik et al., 2015).

En relación a la edad, se encontraron diferencias que

determinan que los docentes más jóvenes tienen mejores habilidades para

navegar, evaluar y almacenar la información, así como para comunicar,

interactuar y colaborar con otras personas a través de medios digitales. Esto

puede ser debido a que estas generaciones están más acostumbradas a

relacionarse con medios digitales desde edades más tempranas, así como

desenvolverse en entornos digitales con mayor frecuencia (Arrosagaray et al.,

2019; Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018), ya sea en el ámbito personal o

profesional. A pesar de todo, es necesario

replantearse, siguiendo a Cabero-Almenara (2020), el mito sobre nativos y

emigrantes digitales puesto que el escenario de la pandemia mundial ha puesto

de manifiesto que la edad no siempre va acompañada de un mayor nivel de

competencia digital.

Finalmente, cabe destacar que poseer un nivel superior

de estudios correlaciona positivamente con presentar mayor nivel competencial,

al igual que señalan otras investigaciones en esta línea (Arrosagaray et al.,

2019; Rosi & Barajas, 2018).

5. Conclusiones

Los avances tecnológicos de los años venideros

impactarán de manera decisiva en las formas de trabajo y en la propia

estructura del mercado laboral, así como en otros aspectos de la vida, la

educación, la sociedad o los servicios (Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019; Elayyan,

2021). Todo este escenario se ha visto acelerado por la pandemia de la

COVID-19, donde multitud de docentes de todas las etapas educativas y a nivel

internacional tuvieron que adaptar sus programaciones didácticas a un entorno

totalmente virtual de formación (Cabero-Almenara, 2020).

Se puede vaticinar, por tanto, que las competencias

demandadas continuarán evolucionando y la sociedad, así como los agentes que la

componen, deberán caminar de manera paralela a las transformaciones que

ocurran, tanto en la reorientación y nivelación profesional en lo relativo a

las competencias de los adultos, como en la educación de las generaciones más

jóvenes. Además, se ha de formar a ciudadanos conscientes, críticos y

participativos en la nueva sociedad (Arranz et al., 2017). Por ello, al hablar

de competencia digital nos referimos a una serie de conocimientos, habilidades

y actitudes. No sólo es importante el saber, sino también el saber ser y

relacionarse con este nuevo modelo social (Blaschke, 2021). Tal y como

mencionaban Brown et al. (2020), anticiparnos al futuro es necesario, puesto

que las decisiones de hoy son siempre una apuesta por lo que pensamos que será

en el futuro.

En este contexto, es de vital importancia que todos

los países se adecúen a esta nueva era generando previsiones futuras con miras

a orientar y definir las prioridades de acción en todos los sectores (Ehlers

& Kellermann, 2019). Sin un

desarrollo político que intervenga en este ámbito, los progresos de la sociedad

digital pueden acentuar y enfatizar las diferencias entre las personas que

poseen competencias digitales adecuadas y aquellas que carecen de las mismas

(Mihelj et al., 2019). De hecho, tal y como menciona Cabero-Almenara (2020), el

último escenario marcado por la COVID-19 donde todos nos hemos visto inmersos

ha puesto de manifiesto las desigualdades educativas y la brecha digital, tanto

en el acceso a la tecnología como en la competencia digital de estudiantes y

profesores. Es por ello que la formación y el aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida

son las alternativas y respuestas adecuadas a los desfases que pueda presentar

cierto sector de la población; más aun siendo conscientes de que la validez

temporal del conocimiento adquirido se ha visto francamente reducida

(Allmendinger et al., 2019; Blaschke, 2021).

En definitiva, la competencia digital –docente-

continúa siendo un reto para la práctica pedagógica, la innovación educativa y la

plena integración de las TIC en la experiencia docente (Rosi & Barajas,

2018; Spiteri & Rundgren, 2018; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2020; Pozo-Sánchez

et al., 2020). Se debe continuar luchando por reducir la brecha existente entre

la competencia digital adquirida y la realmente deseada.

Finalizamos esta investigación señalando la necesidad

de investigar más con docentes de educación de adultos debido al sesgo

existente en la literatura científica que se centra mayormente en las etapas de

educación primaria, secundaria y educación superior. A pesar de todo, la

prospectiva de esta investigación recalca la necesidad de incluir más y mejor

formación en cuanto a la competencia digital se refiere. Solamente así se

logrará que tanto los docentes de todas las etapas educativas como los

distintos miembros que componen la sociedad desarrollen una adecuada

competencia digital para relacionarse con su entorno personal y profesional

(Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019; Rodríguez-García et al., 2019a; Casal et al.,

2021).

6. Limitaciones y

futuras líneas de investigación.

La muestra analizada

es reducida no permitiendo hacer generalizaciones de las conclusiones

obtenidas, aunque con el análisis de la potencia estadística quedan

justificadas dichas propuestas. Como futuras líneas de investigación, se

presentan el valor de la autorregulación en la configuración de entornos

personales de aprendizaje y el desarrollo de la competencia digital en

educación de adultos y la microcredencialización en entornos formativos de esta

índole.

Digital competence in adult education: a study in a Spanish

context

1. Introduction

Today's society is characterised by continuous

movement. We are facing a period of economic, political and social

transformations that are happening very quickly, especially after the radical

metamorphosis that society in general, and the education system in particular,

have undergone in recent years (Cabero-Almenara & Llorente-Cejudo, 2020;

Blaschke, 2021; Cabero-Almenara & Valencia, 2021). In this versatile and

complex context, new ways of relating and communicating with others emerge and,

therefore, new trends and leadership frameworks that guide the development of

new societies, which are increasingly demanding and competitive.

The emergence of new educational environments that

break with the traditional teaching-learning paradigm (Hinojo-Lucena et al.,

2019; Serafín et al., 2019); the re-qualification of citizenship skills for a

socio-occupational environment in continuous transformation (Brown et al.,

2020); the breadth or growth of business markets and the global economy (Ehlers

& Kellermann, 2019); as well as the continuous advancement of digital

technology requires people with a high level of digital competence (Gutiérrez

& Cabero, 2016; Rodríguez-García et al., 2017; Rodríguez-García et al.,

2019a). This situation has become even more evident as a result of the times we

have lived through in the years 2019-2020, where the entire educational

framework (teachers and students at all levels) had to move from a totally face-to-face

teaching to a totally virtual one as a matter of urgency (Cabero-Almenara &

Valencia, 2021; Martínez-Garcés & Garcés-Fuenmayor, 2020). As Arranz et al. (2017) and Elayyan (2021)

have already mentioned, we are facing a possible fourth industrial revolution

due to the imminent evolution of the Internet of Things, robotics, artificial

intelligence, etc. There is no doubt that digital competence is necessary

nowadays (Cappuccio et al., 2016; Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2021; Rolf et al.,

2019). In fact, the European Commission lists it as strictly unavoidable for

being an active, participatory and included member of society, as well as a

requirement for facilitating lifelong learning (Halász & Michel, 2011;

Shonfeld et al., 2021). In general terms, digital competence refers to the set

of skills, abilities and attitudes that facilitate the bidirectional and secure

interrelation with the digital world, with its devices, communication

applications, networks and information access pages (Cabero-Almenara et al.,

2020; Rodríguez-García et al., 2019b). In turn, all these skills allow us to

create, edit and modify digital content, share it with others and collaborate

with them. At the same time, they enable us to provide solutions to problems in

order to achieve effective and creative development in life, work and society

(Guitert et al., 2021).

The set of skills and abilities that businesses and

society itself demand have evolved to position digital competence as a set of

essential skills in their development to relate effectively in 21st century

society (Hatlevik & Christophersen, 2013). Thus, governments need to

understand these new demands and adapt the system to the new needs. In fact,

some authors have pointed out the importance of knowing advanced skills related

to digital competence (artificial intelligence, big data, machine learning...)

in order to improve employability in the future and be effective alternatives

to jobs that will tend to disappear (Arranz et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2020;

Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019). And, consequently, it would be necessary to

implement retraining policies for those populations at risk of disqualification

from their jobs.

There is no doubt that digitalisation is an

unstoppable phenomenon and, therefore, the digital competence of the citizen

must be adapted to these times. Despite its importance, we find inequalities

around age, gender, socioeconomic status, race, education, geography, among

others (Mariscal et al., 2019). In this sense, some of these variables can

become risk factors that can distance these groups from full digital inclusion

and, therefore, be excluded from a system that does not want them because they

do not have a good command of technological knowledge (Kalolo, 2019). However,

the knowledge gap in digital skills can be bridged through training

(Allmendinger et al., 2019).

Training has become a priority line of action for

national and international organisations, whose policies focus on providing

greater access to technology, reducing social inequalities and promoting

greater knowledge and acquisition of digital skills (Rosi & Barajas, 2018).

This, in turn, has led to the current importance of the study of teachers'

digital competence as a reference agent (Johannesen et al., 2014; Cappuccio et

al., 2016; Ilina et al., 2019; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2020; ) and the

succession of research that seeks to ascertain the level of their skills at

different educational stages (Guitert et al., 2020; Lucas et al., 2021).

Lifelong learning is therefore a priority objective and

a response to reduce the inequalities in society (Blaschke, 2021). In Spain,

lifelong learning goes beyond a mere adult education approach. Emphasis is

placed on the importance of preparing learners to be able to learn by

themselves and adapt to the changing demands of the knowledge society,

facilitating both their personal and professional development. It is therefore

important to question the level of digital competence of adult education

teachers, as agents of reference for their learners (Allmendinger et al.,

2019).

2. Metodology

Having established the conceptual foundations that

precede the empirical framework of the study presented here, this research is

framed within a quantitative methodology of a non-experimental and transversal

nature with a descriptive idiosyncrasy (Hernández et al., 2016) in order to

approach the competence level of adult education teachers, as well as to check

whether there are factors that may affect their development (Capuccio et al.,

2016; Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018; Serafín et al., 2019), thus learning

about their perceptions and assessments.

2.1. Specific

objectives

Operationally, the present work aims to achieve the

following objectives: 1) To analyse the level of digital competence of adult

education teachers in Andalusia; 2) To determine whether there are significant

differences between each level of the different independent variables, in

relation to the dependent variables; and 3) To determine the percentage in

which the null hypothesis is rejected in favour of the alternative hypothesis,

and to specify the minimum subjects to find statistical significance.

2.2. Participants and

context

The sample participating in this study is made up of

Continuing Education teachers from public schools in the region of Andalusia,

Spain (N = 140). The sample was obtained by stratified random sampling taking

into account the different provinces of Andalusia (Almeria, Cadiz, Cordoba,

Granada, Huelva and Seville) and the three main types of adult education

centres: Continuing Education Centres (CEPER) and Continuing Education Sections

(SEPER) and Secondary Schools with adult education (IES). The rest of the socio-demographic

data (age, previous ICT training, qualifications, professional experience,

among others) are shown in Table 1.

Socialdemographic data

|

Socialdemographic data |

N |

M(SD) or % |

|

Region |

|

|

|

Almería |

28 |

20 |

|

Cádiz |

16 |

11.43 |

|

Córdoba |

17 |

12.15 |

|

Granada |

49 |

35 |

|

Huelva |

15 |

10.71 |

|

Sevilla |

15 |

10.71 |

|

Centre |

|

|

|

CEPER and SEPER |

97 |

69.28 |

|

IES |

43 |

30.72 |

|

Age |

140 |

35.4(8.56) |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

66 |

47.14 |

|

Female |

74 |

52.86 |

|

Previous ICT training |

|

|

|

Yes |

100 |

71.42 |

|

No |

40 |

28.58 |

|

Degree |

|

|

|

Bachelor’s Degree |

83 |

59.28 |

|

University Degree |

41 |

29.29 |

|

Master’s Degree |

16 |

11.43 |

|

Teaching experience (age) |

140 |

4.98(3.06) |

|

Professional category |

|

|

|

Public servant |

88 |

62.85 |

|

Temporary |

52 |

37.15 |

2.3. Instrument

The data were collected cross-sectionally during the

2019-2020 academic year, based on the application of an online questionnaire on

digital competence. The questionnaire consisted of 91 items, divided into the

five INTEF (2017) areas of digital competence in teaching. The items were based

on each of the indicators that make up each of the five areas: 16 information

and information literacy indicators; 31 communication and collaboration

indicators; 16 digital content creation indicators; 13 safety indicators; and

15 problem-solving indicators. For the validation of the instrument, an

Exploratory Factor Analysis (with varimax rotation and Minimum residual) was

used. The results highlighted that 5 dimensions are sufficient to retain the

data. The root mean square of the residuals (RMSR) was 0.05. This is acceptable

as this value should be closer to 0. Next, the RMSEA (root mean squared error

of approximation) was checked. Its value, .0001, shows good model fit as it is

below .05. Finally, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) is 0.93 - an acceptable value

- considering that it is more than 0.9; a Principal Component Analysis (a PCA

was performed as all dependent variables in the study are metric and the

results highlight that ten dimensions would be the optimal choice); in addition

to the Kaiser-Guttman criterion.

Responses to each item were collected on a 10-level

Likert scale (1 = never; 10 = always). The reliability analysis of the

instrument showed an acceptable value for Cronbach's alpha coefficient (α

=.93). The Wilcoxon test for related samples was used, as it compares the

medians of two related samples to determine whether there are differences

between them. It is the non-parametric version of the t-test for dependent

samples. Its function was as follows: wilcox.test (x, y, paired = TRUE,

alternative = "greater"). The first statistical test determines that,

in terms of gender, there were no statistically significant differences between

males and females in any dependent variable. This is because the p-value =

0.07953, therefore: alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not greater

than 0.

2.4. Data analysis

The analysis of the data obtained was carried out

using the RStudio programming language. This research presents an ANCOVA

design, in which descriptive (such as mean, standard deviation, ...) and

inferential (Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test) analysis techniques

were used. Firstly, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test is a non-parametric test whose

objective is to test whether two samples come from equidistributed populations.

On the other hand, the Kruskal-Wallis test complements the previous one for 3

or more groups.

To carry out these operations, 8 independent variables

were taken into account, two of them being metric variables, and 21 dependent

variables grouped into five groups (Table 2).

Table 2

Research variables

|

Independent variables |

Dependent variables |

|

Centre: CEPER (0) SEPER (1) IES (2) Age Sex Man (0) Women (1) Previous training in

ICT (TIC.For) Yes (0) No (1) Degree Bachelor´s Degree (0) University Degree

(1) Master´s Degree (2) Teacher Experience Professional

Category Public Servant (1) Temporary (2) |

B.1-Information and information literacy B.1.1. Browsing, searching

and filtering information B.1.2. Evaluation of

information, data and digital content B.1.3. Storing and

retrieving information, data and digital content B.2-Communication and collaboration B.2.1. Interacting

through digital technologies B.2.2. Sharing

information and digital content B.2.3. Online citizen

participation B.2.4. Collaboration

through digital channels B.2.5. Netiquette B.2.6. Digital identity

management B.3-Digital content creation. B.3.1. Digital content

development B.3.2. Integration and

re-elaboration of digital content B.3.3. Copyright and

licences B.3.4. Programming B.4-Security B.4.1. Device protection B.4.2. Protection of

personal data and digital identity B.4.3. Health protection B.4.4. Protection of the

environment B.5-Troubleshooting B.5.1. Troubleshooting

technical problems B.5.2. Identification of

technological needs and responses B.5.3. Innovation and

creative use of digital technology |

3. Analysis and

results

In line with our first objective, the descriptive

analysis carried out for each of the independent variables (Figure 1) shows

that the dimensions with the highest mean scores were B.5.4 (identification of

gaps in digital competence) and B.2.4. (collaboration through digital

channels). In this sense, to correct for missing values, they were imputed by

the mean. In contrast, the dimensions with the lowest mean scores were B.3.1

(digital content development), B.3.4 (programming) and B.3.3 (application and

knowledge of copyright and licences).

Descriptive statistics for the research variables

As for the analysis of normality and linearity of the

variables comprising the study, and for research interest, the set of dependent

variables were grouped around their five dimensions (B1-B5). In this sense,

since the data did not meet the assumptions of multivariate normality

(p<.05), but did meet the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance

(p>.05) (see Figure 2), non-parametric tests were used (neither the

criterion of normality nor that of homoscedasticity of variance-covariance is

met).

Robust tests were not necessary because the outliers

were trimmed (imputed) by the median.

The statistical tests used to determine whether there

are significant differences between the different levels of the independent

variables were the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon (WMW) test and the Kruskal-Wallis test

for populations of three or more groups. The first statistical test determines

that, in terms of gender, there were no statistically significant differences

between men and women in any of the dependent variables.

Figure 2

Normality and linearity

between the different variables of the study

However, in terms of professional category (Prof.Cat),

significant differences were found in the dependent variable B.3 (W = 189,

p-value = .04944) and B.5 (W = 159.5, p-value = .01008). Similarly, for the

independent variable prior ICT training (ICT.For), we found significant

differences between participants for B.3 (W = 1559, p-value = .001628) and B.5

(W = 1810, p-value = .03871).

The application of the Kruskal-Wallis test on the

independent variable schools determines that there are significant differences

between all schools (X2(X) = Y; p < .01). Nemenyi and Tukey post hoc

multiple comparisons were used to determine between which groups and how much

difference existed:

·

B.1 (Centre 2 y Centre 1).

·

B.2 (Centre 2 y Centre 0; Centre 2 y Centre 1).

·

B.3 (Centre 2 y Centre 0; Centre 2 y Centre 1).

·

B.4 (Centre 0 y Centre 1; Centre 0 y Centre 2).

·

B.5 (Centre 2 y Centre 0; Centre 2 y Centre 1).

In relation to age, there were only significant

differences between the different ages for B.1 (X2(24) = 23.5, p < .05) and

B.2 (X2(24) = 23.5, p < .05). With respect to degree, we found significant

differences in B.1 (X2(2) = 7.3 p < .01), more specifically between Degree 2

and Degree 1.

As for teaching experience, there were no significant

univariate differences as a function of this independent variable. However,

this was not the case from a multivariate point of view (ANOSIM) (p=.04;

R2=.43).

Finally, in response to our third specific objective,

in statistical terms the power of a test corresponds to the probability of

rejecting the null hypothesis. The power of the test was .9 (power = .9004524).

This means that H0 will be rejected in favour of H1 in 90% of the cases. To

detect effects, 26 subjects are required (n = 26.13751).

4. Discussion

This study provides information on the level of

digital competence of adult education teachers in the Autonomous Community of

Andalusia (Spain), explores their level of digital competence and investigates

the possible variables that may affect their level of qualification, such as

age, context, professional situation, level of studies, among others.

In relation to the first objective, the statistical

analyses carried out determine that the level of digital competence in teaching

is around intermediate levels, especially with regard to the skills for

communicating and collaborating with others; and low in the rest of the

competence areas, especially with regard to technical problem solving. This

situation seems to be reproduced in several research studies, regardless of

whether the sample analysed is from primary, secondary, university or adult

education, as shown by the works of Cabero-Almenara et al. (2020), Casal et al.

(2021), Colás-Bravo et al. (2019) and Moreno-Guerrero et al. (2021).

Today's education professionals seem to be more

skilled in communicating with other people, as well as in carrying out

collaborative work proposals with other people, to the detriment of their

information literacy, i.e. their skills in finding valid, important and

relevant information, as well as in creating digital content, safeguarding

their safety when interacting with the network and solving technical problems

when technologies do not work properly. Thus, this paper finds, as in previous

studies (Rodríguez-García et al., 2019a; Pozo-Sánchez et al., 2020; Casal et

al., 2021), that digital competence continues to be a goal that is not yet

complete, continuing to be a challenge for today's world of education

(Rodríguez-García et al., 2019b). Despite this fact, the sample analysed claims

to be able to identify training deficits in their digital competence, so that

they can strengthen those aspects where there are greater learning gaps.

Continuous teacher training plays an important role here, as this is a key

aspect for adapting to the needs that today's society demands of the different

professionals in any productive sector (Brown et al., 2020).

On the other hand, in relation to the second

objective, that is, with respect to the analyses carried out to check whether

certain variables have an influence on the development of digital competence,

it should be noted that no significant data were found with respect to gender,

unlike other studies that indicate that men tend to use technology more and,

therefore, their digital competence is higher (Mariscal et al., 2019;

Moreno-Guerrero et al., 2019; Serafín et al., 2019; Del Prete & Cabero,

2020). However, the research by Pozo et al. (2020) indicates that women have a

higher level of digital competence in the dimension of digital content

creation, and are more predisposed to the pedagogical use of digital content.

On the other hand, it should be noted that professional

category (civil servant or temporary), as well as previous ICT training,

influence two areas of digital competence: digital content creation (B.3) and

problem solving (B.5). This may be due to, as mentioned by Gudmundsdottir &

Hatlevik (2018) in their research, teachers' low qualifications in digital

competence. Similarly, significant differences in all dimensions of digital

competence are observed with respect to the workplace. Thus, context is

fundamental and a variable that influences the development of digital

competence (Hatlevik et al., 2015).

In relation to age, differences were found that

determine that younger teachers have better skills in navigating, evaluating

and storing information, as well as in communicating, interacting and

collaborating with others through digital media. This may be because these

generations are more accustomed to interacting with digital media from an

earlier age, as well as engaging in digital environments more frequently

(Arrosagaray et al., 2019; Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018), either

personally or professionally.

Nevertheless, following Cabero-Almenara (2020), the myth about digital

natives and migrants needs to be reconsidered, as the global pandemic scenario

has shown that age does not always go hand in hand with a higher level of

digital competence.

Finally, it should be noted that having a higher level

of education correlates positively with having a higher level of competence, as

indicated by other research in this line (Arrosagaray et al., 2019; Rosi &

Barajas, 2018).

5. Conclusions

Technological advances in the coming years will have a

decisive impact on the ways of working and the structure of the labour market

itself, as well as on other aspects of life, education, society and services

(Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019; Elayyan, 2021). This whole scenario has been

accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, where a multitude of teachers at all

educational stages and at international level had to adapt their didactic

programmes to a totally virtual training environment (Cabero-Almenara, 2020).

It can be predicted, therefore, that the skills

required will continue to evolve and society, as well as the agents that make

it up, will have to move in parallel with the transformations that occur, both

in the reorientation and professional levelling in terms of the skills of

adults, as well as in the education of the younger generations. In addition,

conscious, critical and participatory citizens must be trained in the new

society (Arranz et al., 2017). Therefore, when we talk about digital

competence, we refer to a series of knowledge, skills and attitudes. It is not

only important to know, but also to know how to be and relate to this new

social model (Blaschke, 2021). As mentioned by Brown et al. (2020),

anticipating the future is necessary, since today's decisions are always a bet

on what we think the future will be.

In this context, it is of vital importance that all

countries adapt to this new era by generating future forecasts with a view to

guiding and defining priorities for action in all sectors (Ehlers &

Kellermann, 2019). Without policy

development to intervene in this area, the progress of the digital society may

accentuate and emphasise the differences between people who have adequate

digital skills and those who lack them (Mihelj et al., 2019). In fact, as

Cabero-Almenara (2020) mentions, the latest COVID-19 scenario in which we have

all been immersed has highlighted educational inequalities and the digital

divide, both in access to technology and in the digital competence of students

and teachers. It is for this reason that training and lifelong learning are the

appropriate alternatives and responses to the gaps that a certain sector of the

population may present; even more so when we are aware that the temporal validity

of the knowledge acquired has been frankly reduced (Allmendinger et al., 2019;

Blaschke, 2021).

In short, digital competence -teaching- continues to

be a challenge for pedagogical practice, educational innovation and the full

integration of ICT in the teaching experience (Rosi & Barajas, 2018;

Spiteri & Rundgren, 2018; Cabero-Almenara et al., 2020; Pozo-Sánchez et

al., 2020). Efforts to reduce the gap between acquired and desired digital

competence must continue to be pursued.

We conclude this research by pointing out the need for

more research with Adult Education teachers due to the bias in the scientific

literature that focuses mostly on primary, secondary and higher education.

Nevertheless, the prospective of this research emphasises the need to include

more and better training in digital competence. This is the only way to ensure

that both teachers at all educational stages and the different members of

society develop adequate digital competence to interact with their personal and

professional environment (Ehlers & Kellermann, 2019; Rodríguez-García et

al., 2019a; Casal et al., 2021).

6. Limitations and

future lines of research.

The

sample analysed is small and does not allow generalisations to be made about

the conclusions obtained, although the statistical power analysis justifies

these proposals. As future lines of research, the value of self-regulation in

the configuration of personal learning environments and the development of

digital competence in adult education and micro-credentialing in training

environments of this nature are presented..

References

Allmendinger,

J., Kleinert, C., Pollak, R., Vicari, B., Wölfel, O., Althaber,

A., & Künster, R. (2019). Adult Education and

Lifelong Learning. In Education as a Lifelong Process (pp.

325-346). Springer

Arranz,

F. G., Blanco, S. R. & Ruiz, F. J. (2017). Digital skills before

the advent of the fourth industrial revolution. Estudos em Comunicaçao, 1(25),

1-11. https://doi.org/10.20287/ec.n25.v1.a01

Arrosagaray, M., González-Peiteado,

M., Pino-Juste, M., & Rodríguez-López, B. (2019). A comparative study of

Spanish adult students’ attitudes to ICT in classroom, blended and distance

language learning modes. Computers & Education, 134, 31-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.016

Blaschke,

L. M. (2021). The dynamic mix of heutagogy and technology: Preparing learners

for lifelong learning. British Journal of Educational Technology,

1-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13105

Brown,

M., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., Brooks, D. C., Grajek, S., with Alexander, B.,

Bali, M., Bulger, S., Dark, S., Engelbert, N., Gannon, K., Gauthier, A.,

Gibson, D., Gibson, R., Lundin, B., Veletsianos, G.,

& Weber, N. (2020). 2020 EDUCAUSE

horizon report: Teaching and learning edition. EDUCAUSE. https://www.educause.edu/horizon-report-2020

Cabero-Almenara,

J. (2020). Aprendiendo del tiempo de la COVID-19. Revista Electrónica Educare, 24, 4-6.

Cabero-Almenara,

J., & Llorente-Cejudo, C. (2020). Covid-19: transformación radical de la

digitalización en las instituciones universitarias. Campus Virtuales, 9(2), 25-34.

Cabero-Almenara,

J., & Valencia, R. (2021). Y el COVID-19 transformó al sistema educativo:

reflexiones y experiencias por aprender. International

Journal of educational research and innovation, 15, 218-228. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.5246

Cabero-Almenara,

J., Romero-Tena, R., & Palacios-Rodríguez, A. (2020). Evaluation of Teacher

Digital Competence Frameworks Through Expert Judgement: the Use of the Expert

Competence Coefficient. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research

(NAER Journal), 9(2), 275-293.

Casal, L., Barreira,

E. M., Mariño, R., & García, B. (2021). Competencia Digital

Docente del profesorado de FP de Galicia. Pixel-Bit, Revista de Medios

y Educación, (61), 165-196. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.87192

Cappuccio, G., Compagno, G., & Pedone, F. (2016). Digital competence for

the improvement of special education teaching. Journal of E-Learning and

Knowledge Society, 12(4), 93-108. https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1134

Colás-Bravo, P., Conde-Jiménez, J., & Reyes-de-Cózar,

S. (2019). El desarrollo de la competencia digital docente desde un enfoque

sociocultural. Comunicar, 61, 21-32. https://doi.org/10.3916/C61-2019-02

Del

Prete, A., & Cabero, J. (2020). El uso del

Ambiente Virtual de Aprendizaje entre el profesorado de educación superior: un

análisis de género. Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 20(62),

1-20. https://doi.org/10.6018/red.400061

Ehlers,

U.-D., & Kellermann, S. A. (2019). Future skills: The

future of learning and higher education. Results of the International Future

Skills Delphi Survey. Baden-Wurttemberg Cooperative State University.

Elayyan,

S. (2021). The future of education according to the fourth industrial

revolution. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 4(1),

23-30.

Gudmundsdottir,

G. B., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2018). Newly qualified teachers’ professional

digital competence: implications for teacher education. European

Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 214-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1416085

Guitert, M., Romeu, T., & Baztán,

P. (2021). The digital competence framework for primary and secondary schools

in Europe. European Journal of Education, 56(1), 133-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12430

Gutiérrez-Castillo, J.J., & Cabero-Almenara

, J. (2016). Estudio de caso sobre la autopercepción de la competencia digital del

estudiante universitario de las titulaciones de grado de educación infantil y

primaria. Profesorado: Revista de currículum

y formación del profesorado, 20(2), 180-199.

Halász, G., & Michel, A. (2011). Key Competences in

Europe: interpretation, policy formulation and implementation. European

Journal of Education, 46(3), 289-306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2011.01491.x

Hatlevik,

O. E., & Christophersen, K. A. (2013). Digital competence at the beginning

of upper secondary school: Identifying factors explaining digital

inclusion. Computers & Education, 63, 240-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.015

Hatlevik,

O. E., Ottestad, G., & Throndsen, I. (2015).

Predictors of digital competence in 7th grade: a multilevel analysis. Journal

of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(3), 220-231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12065

Hernández,

R., Fernández, C., & Baptista, P. (2016). Metodología

de la Investigación (6ª Ed.). MC Graw Hill Education.

Hinojo-Lucena,

F. J., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., &

Romero-Rodríguez, J. M. (2019). Flipped Classroom Method for the Teacher Training for

Secondary Education: A Case Study in the University of Granada, Spain. International

Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 14(11) 1-7. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i11.9853

Ilina, I., Grigoryeva, Z., Kokorev, A. Ibrayeva, L., & Bizhanova, K. (2019). Digital literacy of the

teacher as a basis for the creation of a unified information educational space.

International Journal of Civil Engineering and

Technology, 10(1), 1686-1693.

Johannesen,

M., Øgrim, L., & Giæver, T. H. (2014). Notion in

motion: Teachers’ digital competence. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy,

9(4), 300-312. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn1891-943x-2014-04-05

Kalolo,

J. F. (2019). Digital revolution and its impact on education systems in

developing countries. Education and

Information Technologies, 24(1), 345-358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9778-3

Lucas,

M., Bem-Haja, P., Siddiq, F., Moreira, A., &

Redecker, C. (2021). The relation between in-service teachers' digital

competence and personal and contextual factors: What matters most?. Computers &

Education, 160, 104052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104052

Mariscal,

J., Mayne, G., Aneja, U., & Sorgner, A. (2019). Bridging the gender

digital gap. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 13(2019-9),

1-12. https://doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2019-9

Martínez-Garcées, J., & Garcés-Fuenmayor, J. (2020).

Competencias digitales docentes y el reto de la educación virtual derivado de

la covid-19. Educación y Humanismo, 22(39), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.17081/eduhum.22.39.4114

Mihelj, S., Leguina, A., & Downey, J. (2019).

Culture is digital: Cultural participation, diversity and the digital

divide. New Media & Society, 21(7),

1465-1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818822816

Moreno-Guerrero,

A.J., Fernández, M.A., & Alonso, S. (2019). Influencia del género en la

competencia digital docente. Revista

Espacios, 40(41).

Moreno-Guerrero,

A. J., Rodríguez-García, A. M., Rodríguez, C., & Ramos, M. (2021).

Competencia digital docente y el uso de la realidad aumentada en la enseñanza

de ciencias en Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Revista Fuentes, 23(1), 108-124. https://doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2021.v23.i1.12050

Pozo,

S., López, J., Fernández, M., & López, J.A. (2020). Análisis correlacional

de los factores incidents en el nivel de competencia

digital del profesorado. Revista

Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 23(1),

143-159. https://doi.org/10.6018/reifop.396741

Pozo-Sánchez,

S., López-Belmonte, J., Rodríguez-García, A. M., & López-Núñez, J. A.

(2020). Teachers’ digital competence

in using and analytically managing information in flipped learning (Competencia

digital docente para el uso y gestión analítica informacional del aprendizaje

invertido). Culture and Education, 32(2),

213-241. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2020.1741876

Rodríguez-García,

A. M., Fuentes, A., & Moreno, A. J. (2019). Competencia digital docente

para la búsqueda, selección, evaluación y almacenamiento de la

información. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 33(3),

235-250.

Rodríguez-García,

A.M., Martínez, N., & Raso, F. (2017). La formación del profesorado en

competencia digital: clave para la educación del siglo XXI. Revista Internacional de Didáctica y

Organización Educativa, 3(2), 46-65.

Rodríguez-García,

A. M., Raso, F., & Ruiz-Palmero, J. (2019a). Competencia digital, educación

superior y formación del profesorado: un estudio de meta-análisis en la Web Of Science. Píxel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, (54), 65-82. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2019.i54.04

Rodríguez-García,

A. M., Trujillo, J. M., &Sánchez, J. (2019b). Impacto de la productividad

científica sobre competencia digital de los futuros docentes: Aproximación

bibliométrica en scopus y web of

science. Revista

Complutense de Educación, 30(2),

623-646. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.58862

Rolf, E., Knutsson, O.,

& Ramberg, R. (2019). An analysis of digital

competence as expressed in design patterns for technology use in

teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology. 50(6), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12739

Rosi,

A. S., & Barajas, M. (2018). Digital competence and educational innovation:

Challenges and opportunities. Profesorado, 22(3), 317-339. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v22i3.8004

Serafín,

Č., Depesova, J., & Banesz,

G. (2019). Understanding digital competences of teachers in Czech Republic. European

Journal of Science and Theology, 15(1), 125-132.

Shonfeld, M., Cotnam-Kappel, M.,

Judge, M., Ng, C. Y., Ntebutse, J. G.,

Williamson-Leadley, S., & Yildiz, M. N. (2021). Learning in digital

environments: a model for cross-cultural alignment. Educational

Technology Research and Development, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09967-6

Spiteri,

M., & Rundgren, S. N. C. (2018). Literature review on the factors affecting

primary teachers’ use of digital technology. Technology, Knowledge and

Learning, 25(1) 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-018-9376-x