Influencia

de variables sociofamiliares en la competencia digital en comunicación y

colaboración

Influence of socio-familial variables on digital competence

in communication and collaboration

Dra. Sonia

Casillas-Martín. Profesora contratada

doctora. Universidad de Salamanca. España

Dra. Sonia

Casillas-Martín. Profesora contratada

doctora. Universidad de Salamanca. España

Dr. Marcos

Cabezas-González. Profesor contratado

doctor. Universidad de Salamanca. España

Dr. Marcos

Cabezas-González. Profesor contratado

doctor. Universidad de Salamanca. España

Dra. Ana

García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso. Catedrática

de Universidad. Universidad de Salamanca. España

Dra. Ana

García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso. Catedrática

de Universidad. Universidad de Salamanca. España

Recibido:

2021/09/07 Revisado: 2021/10/04 Aceptado: 2021/11/13 Preprint: 2021/12/09 Publicado: 2022/01/07

Cómo citar este artículo:

Casillas-Martín, S.,

Cabezas-González, M., & García-Valcárcel Muñoz-Repiso, A. (2022).

Influencia de variables sociofamiliares en la competencia digital en

comunicación y colaboración [Influence of socio-familial variables on digital competence in communication and collaboration].

Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación,

63, 7-33. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.84551

RESUMEN

Las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación

(TIC) se utilizan en todos los sectores, incluido el educativo y una

competencia básica como es la digital, debe ser desarrollada desde la escuela.

Para conseguir políticas educativas eficaces que integren las TIC en los

sistemas educativos y fomenten el desarrollo de esta competencia, es muy

importante conocer la influencia que pueden tener diferentes variables sociales

en su adquisición. En este artículo se presenta un estudio de tipo no

experimental que tiene por objeto evaluar la competencia digital de los

estudiantes de enseñanza obligatoria e identificar el impacto que tienen en

ella, diferentes variables sociofamiliares. Se diseñó una investigación

descriptiva transversal utilizando una metodología cuantitativa. Se trabajó con

una muestra de 807 estudiantes y se utilizó una prueba de resolución de

problemas para la recogida de datos. Los resultados muestran un nivel medio en

conocimiento y capacidades digitales influenciado por los antecedentes

económicos y culturales de la familia, así como por el acceso de los

estudiantes a los dispositivos digitales desde sus casas. Esta situación debe

de ser motivo de reflexión en los centros educativos, para implementar

programas curriculares que fortalezcan este tipo de competencias.

ABSTRACT

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are

used in all sectors, including education, and basic competences, such as

digital competence, should be developed at school. It is very important to

understand the influence that different social variables can have on the

acquisition of digital competence in order to implement effective educational

policies that integrate ICT in educational systems and promote its advancement.

This article presents a non-experimental study that aims to evaluate the

digital competence of students in compulsory education and to identify the

impact of different social variables. A cross-sectional descriptive research

was designed using a quantitative methodology. We worked with a sample of 807

students, and a problem-solving test was used for data collection. The results

show an average level of digital knowledge and skills influenced by family

economics and cultural backgrounds, as well as the students' access to digital

devices within their homes. This situation should be a cause for reflection in

educational centres, in order to implement curricular programs that strengthen

this type of skill.

PALABRAS CLAVES · KEYWORDS

Tecnología educacional; competencia digital;

tecnología de la comunicación; educación básica; evaluación de la tecnología.

Educational technology; digital competence;

communication technology; basic education; technology assessment.

1. Introducción

En

este artículo se presenta un estudio en el marco de un proyecto de

investigación I+D, financiado por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad

dentro del Programa Estatal de Fomento de la Investigación Científica y Técnica

de Excelencia, del gobierno de España, cuya finalidad es la de evaluar la

competencia digital de estudiantes de educación obligatoria y estudiar las

relaciones y la incidencia que se establecen entre el nivel de competencia

digital de los mismos y algunas características (variables) sociofamiliares.

En

la última década, las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación (TIC) han

originado numerosos cambios sociales, económicos y culturales (Sánchez-Caballé et al., 2020). La digitalización de las actividades

humanas, que difumina cada vez más los límites entre la vida personal y

profesional (Ying-Jung et al., 2019) ha obligado a los ciudadanos a desarrollar

nuevas competencias tanto en el ámbito de lo personal como de lo profesional y

una de las primordiales es la competencia digital (Siddiq

et al., 2016), clave para el tratamiento de la información, el rendimiento

académico y el éxito profesional (Pagani et al., 2016).

Las

sociedades actuales, necesitan que sus sistemas educativos preparen ciudadanos

y profesionales acordes con las nuevas exigencias de un mercado laboral en

constante cambio (López Belmolte et al., 2020). Las

TIC se utilizan en todos los sectores, incluido el educativo (Gutiérrez

Castillo et al., 2017) y una competencia básica como es la digital, debe ser

desarrollada desde la escuela.

Aunque

esta competencia aparece cada vez más en el discurso público, en los documentos

de política educativa y en la investigación social y pedagógica, su concepto

aún no está normalizado (Pöntinen & Räty-Záborszky, 2020). Son diferentes los términos

empleados para identificar y analizar los conocimientos, capacidades y

actitudes que la engloban: alfabetización digital (Ivanovich

et al., 2020; McDougall et al., 2019; Smith et al.,

2020), alfabetización mediática (Cho et al., 2020; De La Fuente Prieto et al.,

2019; González-Fernández et al., 2019), competencia digital (Casillas-Martín et

al., 2020a; Holguin-Alvarez et al., 2020; Reisoğlu & Çebi, 2020),

entre otros. Los más utilizados son los de competencia

digital y alfabetización digital (Pöntinen

& Räty-Záborszky, 2020).

La

Unión Europea (2018) reconoce, en su recomendación C 189, a la competencia

digital como una de las ocho competencias clave para el ciudadano del siglo XXI

(Recio Muñoz et al., 2020), y la define como:

El uso seguro, crítico y responsable de las

tecnologías digitales para el aprendizaje, en el trabajo y para la

participación en la sociedad, así como la interacción con estas. Incluye la

alfabetización en información y datos, la comunicación y colaboración, la

alfabetización mediática, la creación de contenidos digitales (incluida la

programación), la seguridad (incluido el bienestar digital y las competencias

relacionadas con la ciberseguridad), asuntos relacionados con la propiedad

intelectual, la resolución de problemas y el pensamiento crítico. (p. 9)

Evaluar

la competencia digital de los estudiantes ha sido, en los últimos años, una

preocupación científica en el área de las Ciencias Sociales y de la Educación (véase por ejemplo: Cabezas-González & Casillas-Martín,

2018; López-Meneses et al., 2020; Llorent-Vaquero et

al., 2020; Martínez-Piñeiro et al., 2019; Nowak,

2019; Wild & Schulze Heuling,

2020).

Para

desarrollar políticas educativas eficaces que integren las TIC en los sistemas

educativos y fomenten el desarrollo de esta competencia es muy importante

conocer la influencia que pueden tener diferentes variables sociales en su

adquisición y desarrollo.

En

este sentido, se han realizado distintas investigaciones, siendo las variables

más estudiadas las de género y edad. En el contexto español, en un estudio

sobre el nivel de competencia digital de estudiantes universitarios, se

concluye que los hombres superan a las mujeres en conocimientos y manejo de los

dispositivos digitales (Cabezas-González et al., 2017). Respecto a la influencia

de la edad en la competencia digital de profesores no universitarios españoles,

hay evidencias que apuntan que los mayores de 40 años se sienten menos

competentes y motivados para emplear tecnologías en las áreas de la

información, la alfabetización informacional y la creación de contenido

educativo digital (López Belmolte et al., 2020).

También

se ha investigado sobre la influencia de variables sociofamiliares. En el

contexto ruso, en un estudio con alumnos universitarios, Kozlov

et al. (2019), señalan que las barreras que impiden el desarrollo de la

competencia digital dependen de tres factores: geográficos-regionales,

socioeconómicos y personales. En Corea, Kim et al. (2018), demostraron que los

estudiantes universitarios que viven en un ambiente digitalmente enriquecido en

el hogar y en la escuela son más propensos a adoptar, de manera eficaz, las

tecnologías digitales para el aprendizaje. En Noruega, se comprobó que los

antecedentes familiares, en términos de integración lingüística y número de libros

en el hogar, eran predictores del grado de competencia digital de los alumnos

de séptimo grado (Hatlevik et al., 2014). En Kosovo, Shala and Grajcevci (2018)

concluyeron que en el desarrollo de esta competencia influyen positivamente la

inclusión en entornos académicos, una buena posición socioeconómica y residir

en áreas urbanas frente a rurales.

En

cuanto al desarrollo y evaluación de la competencia digital, existen diferentes

estándares e indicadores tanto de los ciudadanos como de los profesores y de

los estudiantes: Technological Pedagogical

Content Knowledge (TPACK) (Mishra & Koehler,

2006), modelo Krumsvik (Krumsvik,

2011), Standards for Students, a Practical Guide for Learning with

Technology (ISTE, 2016), estándares de competencia

TIC para docentes (ECD-TIC) (UNESCO, 2008), National Educational Technology Standards for Teachers

(ISTE, 2008), Marco Europeo para la Competencia digital de los Educadores (DigCompEdu) (Punie, 2017), Marco

Común de la Competencia Digital Docente (INTEF, 2017), entre otros. En el

estudio que se presenta se ha seguido uno de los modelos referentes para el

desarrollo de competencias digitales en Europa, el Marco Europeo de Competencia

Digital (DigComp).

En

el año 2013, la Comisión Europea publicó el Marco para el Desarrollo y la

Comprensión de la Competencia Digital en Europa (DigComp

1.0) (Ferrari, 2013), modificado en 2016 por el Marco Europeo para la

Competencia Digital de los Ciudadanos (DigComp 2.0) (Vuorikari et al., 2016) y actualizado en 2017 por DigComp 2.1. (Carretero et al., 2017). Este modelo, con un

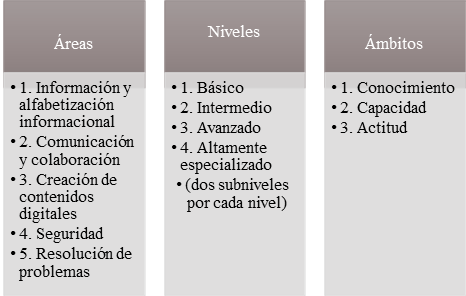

total de veintiuna competencias digitales, estructura sus dimensiones en cinco

áreas, cuatro niveles, con dos subniveles cada uno, y tres ámbitos (Figura 1).

Figura 1

Estructura-dimensiones

de la competencia digital DigComp 2.1

Esta

investigación se centra en el área competencial de comunicación y colaboración,

cuyas competencias digitales son: interacción por medio de tecnologías

digitales, compartir información y contenidos digitales, participación

ciudadana en línea, colaboración mediante tecnologías digitales, netiqueta y

gestión de la identidad digital.

Las variables

sociofamiliares analizadas en este trabajo (género, curso académico, nivel

económico-cultural de la familia, acceso a dispositivos digitales) fueron

delimitadas tras una revisión de investigaciones sobre el tema.

2. Metodología

Se

empleó una metodología cuantitativa (prueba objetiva y escala de actitudes) con

un diseño de corte descriptivo y transversal, puesto que la información se

recogió en un único momento, durante el curso académico 2018-2019.

2.1 Objetivos

Se plantean dos objetivos:

1. Conocer el nivel

de competencia digital que tienen los estudiantes de educación obligatoria

(12-14 años) de algunas provincias españolas en el área de comunicación y

colaboración, teniendo en cuenta los ámbitos de conocimiento, capacidad y

actitud.

2. Identificar la

influencia de variables sociofamiliares en el desarrollo de esta área

competencial por parte de estos escolares.

2.2 Participantes

La

evaluación se llevó a cabo en la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León

(España). Se utilizó un tipo de muestreo aleatorio estratificado (Casal &

Mateu, 2003) lo que llevó a trabajar con una muestra de 807 estudiantes (668 de

último curso de Educación Primaria y 139 de primer curso de Educación

Secundaria Obligatoria) de entre 12 y 14 años, de 18 centros educativos (Tabla 1).

Desde el punto de vista del género, se cuenta con una muestra equilibrada (el

51.4% pertenecen al femenino y el 48.6% al masculino).

Tabla 1

Distribución de la

muestra

|

Muestra total |

Curso |

Género |

||||||

|

6º Primaria |

1º Secundaria |

Femenino |

Masculino |

|||||

|

N |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

807 |

668 |

82.8 |

139 |

17.2 |

415 |

51.4 |

392 |

48.6 |

2.3 Prueba de evaluación

Para

la elaboración del instrumento de evaluación se llevó a cabo una revisión

documental sobre los ámbitos de la competencia digital, con la intención de

formular un modelo de indicadores en el que basar su diseño y se tomó como

referencia el modelo DigComp 1.0. (Ferrari, 2013).

Teniendo en cuenta la estructura de este modelo, para el área competencial de

comunicación y colaboración fueron planteados un total de 69 indicadores

adaptados a la población objeto de estudio, organizados en tres ámbitos

(conocimiento, capacidad y actitud) y en tres niveles (básico, intermedio y

avanzado). Estos indicadores pueden consultarse en: “Modelo de indicadores para

evaluar la competencia digital de los estudiantes tomando como referencia el

modelo DigComp (INCODIES)” (García-Valcárcel et al.,

2019); documento más amplio en el que se recogen un total de 325 indicadores

relativos a las cinco áreas de la competencia digital.

Para

la validación del contenido del modelo de esta área competencial se utilizó el

método de jueces. Un total de 17 expertos en el diseño de indicadores de

evaluación, en competencia digital y profesionales en ejercicio pertenecientes

a distintos contextos educativos (educación obligatoria, universidad, gestión

educativa), evaluaron la importancia, la pertinencia y la claridad de los

indicadores por medio de un cuestionario online tipo escala Likert de 4 grados

(1-ninguna, 2-poca, 3-bastante, 4-mucha).

Teniendo

en cuenta el modelo de indicadores y los criterios para la elaboración de

instrumentos de recogida de información (McMillan

& Schumacher, 2005), se diseñó un banco de ítems para esta área.

Esta

batería de ítems fue depurada por medio de una revisión de expertos, dando

lugar a la primera versión de la prueba de evaluación que fue aplicada a una

muestra piloto de 288 alumnos de educación obligatoria (incluyendo estudiantes

de 6º curso de Educación Primaria y 1º de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria),

calculándose los niveles de dificultad de los ítems de conocimiento y

capacidad, así como la fiabilidad de los de actitud. Con los resultados se

procedió a la elaboración de la prueba final de esta área competencial (Tabla

2).

Tabla 2

Estructura de la

prueba de evaluación definitiva

|

Área |

Número de

ítems por ámbitos de competencia |

Número de

ítems por niveles de competencia |

||||

|

Conocimiento |

Habilidad |

Actitud |

Básico |

Intermedio |

Avanzado |

|

|

2.1. Interacción

mediante nuevas tecnologías |

1 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

2.2. Compartir

información y contenidos |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2.3. Participación ciudadana

en línea |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

2.4. Colaboración

mediante canales digitales |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

2.5. Netiqueta |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

2.6. Gestión de la

identidad digital |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

TOTAL A2.

Comunicación y colaboración |

8 |

10 |

7 |

8 |

3 |

|

Para

evaluar los conocimientos y las capacidades, se diseñó una prueba objetiva con

preguntas que presentaban situaciones reales en las que los estudiantes tenían

que tomar decisiones, seleccionando una respuesta correcta de entre cuatro

opciones posibles. Para las actitudes, se utilizó una escala tipo Likert

previamente validada, compuesta por 6 enunciados referidos, cada uno de ellos,

a una afirmación sobre el área competencial con 5 opciones de respuesta (1 muy

en desacuerdo, 5 muy de acuerdo). La versión definitiva de la prueba para

evaluar la competencia digital de los estudiantes en todas las áreas

competenciales, denominada ECODIES, se encuentra disponible en el repositorio

documental GREDOS de la Universidad de Salamanca

(https://gredos.usal.es/handle/10366/139397). La información de tipo

sociofamiliar se recopiló por medio de una encuesta compuesta por 17 ítems.

Una

vez obtenido el permiso de las autoridades de la Administración Educativa, del

Comité ético de la Universidad de Salamanca, de los centros educativos y de las

familias, la aplicación de la prueba de evaluación se realizó por medio de un

sitio web, diseñado ad hoc, para facilitar su cumplimentación por parte de los

escolares (puede consultarse en: https://www.ecodies.es/). Todos los centros colaboraron

de manera voluntaria y se encargaron de obtener los permisos de las familias y

de los estudiantes, así como de aplicar la prueba en el horario lectivo,

siempre siguiendo las pautas y protocolos preparados por los investigadores.

Una vez aplicada la prueba, los docentes pudieron acceder a un informe de su

grupo de clase y de cada uno de sus estudiantes para conocer el nivel

competencial, así como poderlo comparar con la muestra total.

Respecto

a la validez, se tuvo en cuenta el contenido (marco teórico de referencia,

modelo DigComp) y la estructura (dimensiones de la

prueba). Se utilizó la técnica de expertos, actuando como jueces 10 profesores

universitarios expertos en tecnología educativa. En relación con la validez

estructural, se realizó un Análisis Factorial (AF) de componente principales

con el método de rotación Varimax con normalización

Kaiser para las diferentes áreas competenciales. El resultado del mismo proporcionó un valor KMO aceptable y un índice de

esfericidad de Barlett altamente significativo en

todos los casos (p<0.001) (Casillas-Martín et al., 2020b). Para constatar la

fiabilidad, como consistencia interna, tanto de la prueba completa como de las

pruebas específicas de conocimiento, capacidad y actitud; se calculó el índice α

de Cronbach, el α Ordinal o modelo de factor común (medida de consistencia

interna) (Welch & Comer, 1998), además del coeficiente Theta de Armor (modelo de componentes principales). Estos últimos se

consideran más apropiados para escalas de menos de cinco categorías o ítems

dicotómicos. El α Ordinal y Theta de Armor se

calcularon en base a las correlaciones tetracóricas y

los pesos factoriales rotados, siguiendo las indicaciones de Domínguez-Lara

(2018).

Los

índices de α de Cronbach obtenidos se consideran poco aceptables (<.70)

(Tabla 3). Esto puede ser debido a que este estadístico presupone el carácter

continuo de las variables y es considerado inadecuado para escalas con menos de

cinco categorías, siendo nuestras respuestas de carácter dicotómico (exceptuando

la escala de actitudes). Teniendo en cuenta las apreciaciones de algunos

autores en relación con la aplicación de este índice al utilizar una escala

dicotómica (Oliden & Zumbo, 2008; Zumbo et al.,

2007), se utilizó el Índice de Atenuación (IA) para comparar el α de

Cronbach con el α Ordinal. Los valores obtenidos fueron satisfactorios

(>.60), siendo suficientes para garantizar la fiabilidad de las escalas

(Morales et al., 2003).

Tabla 3

Fiabilidad de la

prueba de evaluación definitiva

|

Área |

Ámbito |

N |

α Cronbach |

α ordinal |

Theta de

Armor |

Índice de

Atenuación (IA) |

N de

elementos |

|

A2 |

Conocimiento-capacidad |

807 |

.58 |

0.70 |

0.71 |

17% |

18 |

|

Actitudes |

793 |

.73 |

0.81 |

0.80 |

11% |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Competencias |

N |

α Cronbach |

α ordinal |

Theta de Armor |

Índice de Atenuación (IA) |

N de elementos |

|

|

A2.1.

Interacción mediante nuevas tecnologías |

807 |

.43 |

.63 |

.63 |

32% |

3 |

|

|

A2.2.

Compartir información y contenidos |

807 |

.40 |

.60 |

.60 |

34% |

3 |

|

|

A2.3.

Participación ciudadana en línea |

807 |

.33 |

.68 |

.68 |

52% |

3 |

|

|

A2.4. Colaboración

mediante canales digitales |

807 |

.24 |

.66 |

.66 |

64% |

3 |

|

|

A2.5.

Netiqueta |

807 |

.42 |

.72 |

.72 |

42% |

3 |

|

|

A2.6. Gestión

de la identidad digital |

807 |

.21 |

.63 |

.63 |

67% |

3 |

|

|

Prueba Área 2 completa |

793 |

.40 |

.86 |

.86 |

19% |

24 |

3. Análisis y resultados

Interesa

conocer, además de los niveles competenciales en el área de comunicación y

colaboración de los estudiantes, si existen diferencias significativas en los

resultados de la evaluación, debido a la influencia de variables sociofamiliares

(género, curso académico, nivel económico y cultural de la familia, acceso a

dispositivos digitales). La variable “nivel económico y cultural de la

familia”, para evitar problemas de privacidad al indagar sobre el nivel de

estudios o profesión de la familia, se define como: acompañamiento familiar

para la realización de deberes, lectura de libros en la familia (fuera de la

escuela) y viajes y vacaciones familiares. La variable “acceso a dispositivos

digitales” se define como: dispositivos con los que cuenta el estudiante en el

hogar (ordenador, tablet, reproductor de música,

móvil con conexión a Internet, impresora, lector de libros digitales,

videoconsola, televisión). Estas variables son elegidas tras una revisión

bibliográfica sobre variables sociofamiliares relevantes en la adquisición de

la competencia digital.

Se

realizan análisis inferenciales mediante comparación de medias, utilizando el

programa SPSS v.25. Dado el alto número de sujetos y una vez comprobados los

supuestos paramétricos de normalidad (prueba de Kolmogorov-Smirnov

y Shapiro-Wilk), donde se confirma que se trata de una distribución normal

(>0,05), se opta por la utilización de pruebas paramétricas, de contraste de

hipótesis; en concreto la prueba de t de Student y la

prueba ANOVA, lo que permite comprobar la existencia de diferencias

estadísticamente significativas.

De acuerdo con los objetivos propuestos, a

continuación, se presentan los principales resultados obtenidos.

En

cuanto al área competencial de comunicación y colaboración digital en los tres

ámbitos (conocimiento, capacidad y actitud), los estudiantes demuestran un

nivel medio en conocimientos y capacidades (=9.66). Para calcular las

medias correspondientes se creó una variable mediante la suma de las

competencias de conocimiento y capacidad, siendo el rango de respuesta de 0 a

18. En cambio, las actitudes son altamente positivas, con una media de 4.32

sobre 5 (Tabla 4).

Tabla 4

Estadísticos

descriptivos

|

Área 2 |

N |

Mín |

Máx |

|

DT |

Asimetría |

Curtosis |

||

|

Y1 |

SE |

g2 |

SE |

||||||

|

Conocimiento-capacidad

(máx. 18) |

807 |

0 |

17 |

9.66 |

2.98 |

-.36 |

.09 |

-.10 |

.17 |

|

Actitud

(máx. 5) |

793 |

0 |

5 |

4.34 |

.72 |

-2.39 |

.09 |

9.06 |

.17 |

Si

nos centramos en los datos relativos a la influencia de factores

sociofamiliares, en cuanto a la variable género, no se han encontrado

diferencias significativas en ninguno de los ámbitos evaluados (conocimiento,

capacidad y actitud); tampoco en los datos de la prueba de conocimiento y

capacidad (Tabla 5).

Tabla 5

Estadísticos

descriptivos y prueba t de Student para la variable

género

|

Género |

Masculino |

Femenino |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov |

t-Student |

d (Cohen) |

|||||

|

N |

(DT) |

N |

(DT) |

Z |

gl |

p |

t |

p |

||

|

CN (sobre 8) |

392 |

4.18 (1.61) |

415 |

4.36 (1.53) |

.13 |

607 |

.00 |

1.47 |

.14 |

.11 |

|

CP (sobre 10) |

392 |

5.29 (2.05) |

415 |

5.47 (1.71) |

.12 |

577 |

.00 |

1.18 |

.24 |

.01 |

|

AC (sobre 5) |

387 |

4.26 (.76) |

406 |

4.35 (.75) |

.18 |

607 |

.00 |

1.46 |

.14 |

.13 |

|

PCC (sobre 18) |

387 |

9.46 (3.10) |

406 |

9.83 (2.62) |

.09 |

607 |

.00 |

1.58 |

.11 |

.12 |

En

relación con la variable curso académico al que pertenecen los estudiantes, no

se encuentran diferencias significativas en los ámbitos de conocimiento y

capacidad, pero sí en el de actitud (<.05). Los estudiantes de 6º curso de

Educación Primaria manifiestan una actitud más positiva (media de 4.34 frente a

4.10). El tamaño del efecto relativo a la actitud puede considerarse entre bajo

y moderado (d=.32) (Tabla 6).

Tabla 6

Estadísticos

descriptivos y prueba t de Student para la variable

curso

|

Curso |

6º

Primaria |

1º ESO |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov |

t-Student |

d

(Cohen) |

|||||

|

N |

(DT) |

N |

(DT) |

Z |

gl |

p |

t |

p |

||

|

CN (sobre 8) |

668 |

4.31

(1.54) |

139 |

4.06

(1.72) |

.13 |

607 |

.00 |

1.40 |

.16 |

.16 |

|

CP (sobre 10) |

668 |

5.42

(1.86) |

139 |

5.18

(1.99) |

.12 |

607 |

.00 |

1.14 |

.25 |

.13 |

|

AC (sobre 5) |

658 |

4.34

(.70) |

135 |

4.10

(.98) |

.18 |

112.17 |

.00 |

2.25 |

.02 |

.32 |

|

PCC(sobre 18) |

658 |

9.73

(2.81) |

135 |

9.24

(3.17) |

.09 |

607 |

.00 |

1.52 |

.13 |

.17 |

Respecto

al nivel económico y cultural de la familia, clasificado en cuatro niveles (muy

bajo, bajo, medio, alto), existen diferencias significativas (p<.05) en

conocimiento y en capacidad, pero no en actitud. Son los estudiantes de

familias con nivel económico-cultural alto los que mejor conocimiento y

capacidad demuestran. El tamaño del efecto es pequeño, salvo en conocimiento

que se aproxima a medio (Tabla 7).

Tabla 7

Estadísticos

descriptivos y prueba t de Student para la variable

nivel económico-cultural de la familia

|

NECF |

Muy

bajo |

Bajo |

Medio |

Alto |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov |

ANOVA |

d

(Cohen) |

|||||||

|

N |

(DT) |

N |

(DT) |

N |

(DT) |

N |

(DT) |

Z |

gl |

p |

F |

p |

||

|

CN (sobre 8) |

21 |

3.91

(1.30) |

52 |

4.02

(1.49) |

379 |

4.09

(1.59) |

355 |

4.54

(1.56) |

.13 |

607 |

.00 |

4.51 |

.00 |

.30 |

|

CP(sobre 10) |

21 |

5.62

(1.85) |

52 |

5.30

(1.93) |

379 |

5.17

(1.94) |

355 |

5.64

(1.79) |

.12 |

607 |

.00 |

2.60 |

.05 |

.20 |

|

AC (sobre 5) |

20 |

3.88

(1.52) |

50 |

4.22

(.72) |

373 |

4.31

(.72) |

350 |

4.34

(.75) |

.18 |

112.17 |

.00 |

1.64 |

.18 |

.20 |

|

PCC(sobre 18) |

20 |

9.55

(2.42) |

50 |

9.31

(2.91) |

373 |

9.27

(2.99) |

350 |

10.16

(2.68) |

.09 |

607 |

.00 |

4.71 |

.00 |

.20 |

Nota. NECF=Nivel

económico-cultural de la familia. CN= Conocimiento, CP= Capacidad, AC= Actitud,

PCC= Prueba Conocimiento-capacidad

4. Conclusiones y discusión

En

esta investigación se ha identificado el nivel de competencia digital, en el

área de comunicación y colaboración, que tienen los estudiantes de educación obligatoria

(12-14 años) teniendo en cuenta los tres ámbitos competenciales de

conocimiento, capacidad y actitud. También se ha comprobado la influencia de

variables sociofamiliares en el desarrollo de esta área competencial.

El

nivel de competencia digital demostrado por los estudiantes es básico en

conocimiento y en capacidad, si bien las actitudes son muy positivas. Los

resultados coinciden con otras investigaciones, como la realizada en la

Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia (España) por Martínez-Piñeiro et al. (2019), en

la que los alumnos alcanzan un aprobado (5 sobre 10) en esta área competencial.

Esta situación tiene que ser motivo de reflexión en los centros educativos,

para implementar programas curriculares que fortalezcan este tipo de

competencias.

Además,

es muy importante conocer la influencia que pueden llegar a tener las variables

sociofamiliares en la adquisición y desarrollo de esta competencia para diseñar

y poner en práctica políticas educativas eficaces y compensatorias. Este

trabajo pretende contribuir a este objetivo.

Los

resultados obtenidos muestran, al igual que en otras investigaciones (Pérez

Escoda et al., 2016; Wong & Kemp, 2018), que las variables sociofamiliares

determinan la adquisición y desarrollo de estas competencias digitales: interacción

por medio de tecnologías digitales, compartir información y contenidos

digitales, participación ciudadana en línea, colaboración mediante tecnologías

digitales, netiqueta y gestión de la identidad digital.

Así,

se ha podido identificar que el nivel económico y cultural de la familia

influye significativamente en el ámbito de conocimiento y de capacidad, pero no

en el de actitud. Los estudiantes de familias cuyo nivel económico y cultural

es alto, son los que demuestran mejor conocimiento y capacidad en comunicación

y colaboración. Estos resultados corroboran la importancia de esta variable

como predictora de la competencia digital (Ames, 2016; Claro et al., 2015).

También la influencia del acceso a dispositivos digitales, siendo las

diferencias significativas en todos los ámbitos (conocimiento, capacidad y

actitud). Los que tienen la posibilidad de acceder a más dispositivos,

demuestran mejores conocimientos, capacidades y actitudes en el área

competencial de comunicación y colaboración. Esto contrasta con los hallazgos

de otras investigaciones, en las que se concluye que la posesión y exposición a

este tipo de dispositivos no aumenta el nivel de competencia digital (Colás et al., 2017; Casillas-Martín & Cabezas-González,

2019).

No

se ha podido verificar la influencia del género ni del curso académico

(relacionado con la edad) en el nivel competencial. Se puede decir que no

existen diferencias significativas en función del género, y con respecto al

curso académico solo existen diferencias en la actitud, a favor de los

estudiantes de menor edad (Educación Primaria). Respecto al género, nuestros

resultados coinciden con los de otros trabajos (Centeno & Cubo, 2013;

Roblizo & Cózar, 2015), pero contrastan con los de otras investigaciones

(Cabero et al., 2008; Cabezas-González et al., 2017; Mayor Buzón et al., 2019;

Pozo Sánchez et al., 2020), en las que sí se demuestra la influencia de esta

variable. En cuanto a la edad, también se observan divergencias entre estudios

y nuestros resultados se sitúan en la línea de algunos autores (García et al.,

2014; Martos et al., 2016; Moreno Guerrero et al., 2020; Rabin et al, 2020)

pero difieren con los de otros, como Romero y Minelli

(2011).

Por

todo ello y a la luz de los hallazgos encontrados en esta investigación se

puede concluir que la competencia digital, en el área de comunicación y

colaboración, no depende ni del género ni del curso académico (relacionado con

la edad), pero sí del nivel económico y cultural de la familia y del acceso a

dispositivos digitales que tenga el estudiante en su entorno personal y

familiar. A mayor nivel económico y cultural y más dispositivos a los que poder

acceder, se observa más conocimiento y capacidad digital en esta área.

Es

necesario señalar algunas limitaciones de esta investigación. Las variables

concretas estudiadas podrían limitar una explicación más global y comprensiva

de los factores que influyen en el nivel de competencia digital de los

escolares. Además, la validación del modelo podría complementarse con la

realización de un Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio (AFC).

Para

terminar, posibles líneas de investigación futuras podrían dirigirse al estudio

de las relaciones y la incidencia entre el nivel de competencia digital de

escolares con edades diferentes a las contempladas y otras características

(variables) de tipo personal, social y familiar distintas a las utilizadas en

este trabajo. Además, sería interesante y pertinente proponer otras estrategias

complementarias de evaluación que permitan verificar, de una manera objetiva,

la competencia digital de estos escolares. Todo ello permitiría completar esta

línea de investigación. También sería muy oportuno replicar este trabajo en la

actualidad, una vez concluida la situación de confinamiento originada por la

pandemia del COVID-19, en la que fue necesario recurrir al uso de dispositivos

tecnológicos para poder continuar, desde el hogar, con el desarrollo de los

procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje iniciados durante el curso académico

2019-2020 en los centros escolares españoles. Sería de gran interés comprobar

si, tras esta situación vivida, el nivel competencial de los escolares ha variado así como la influencia en el nivel competencial de

las variables sociofamiliares. Ello ayudaría a orientar las políticas de

integración de las TIC en los centros docentes.

Financiación

Proyecto

I+D “Evaluación de la competencia digital de los estudiantes de educación obligatoria

y estudio de la incidencia de variables sociofamiliares (EVADISO)”.

EDU2015-67975-C3-3-P, MINECO/FEDER).

Influence of socio-familial variables on

digital competence in communication and collaboration

1.

Introduction

This article presents a study that is part of an

R&D research project funded by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness

within the Excellence State Program for the Fostering of Scientific and

Technological Research of the Spanish Government, whose purpose is to assess

the digital competence of compulsory education students and study the

relationships and incidence that are established between their level of digital

competence and certain socio-familial characteristics (variables).

Over the last decade, Information and Communication

Technology (ICT) has led to numerous social, economic and cultural changes

(Sánchez-Caballé et al., 2020). The digitalization of human activities, which

increasingly blurs the boundary between personal and professional life (Ying-Jung

et al., 2019), has forced citizens to develop new competences to use both

personally and professionally, digital competence being of major importance

(Siddiq et al., 2016), since it plays a key role in the processing of

information, academic performance and professional success (Pagani et al.,

2016).

Today’s societies need their education systems to

prepare citizens and professionals to meet the new requirements of a constantly

changing labor market (López Belmolte et al., 2020). ICT is used in every area,

including education (Gutiérrez Castillo et al., 2017) and the development of an

aspect as essential as digital competence should begin at school.

Although this competence is an increasingly common

topic in public discourse, its idea is not yet standardized in educational

policy texts and social and pedagogical research (Pöntinen &

Räty-Záborszky, 2020). Different terms are used to identify and analyze the

knowledge, skills and attitudes that encompass it: digital literacy (Ivanovich

et al., 2020; McDougall et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2020), media literacy (Cho

et al., 2020; De La Fuente Prieto et al., 2019; González-Fernández et al.,

2019), digital competence (Casillas-Martín et al., 2020a; Holguin-Alvarez et

al., 2020; Reisoğlu & Çebi, 2020), among others. The most commonly

used are digital competence and digital literacy (Pöntinen &

Räty-Záborszky, 2020).

In its recommendation C 189, the European Union (2018)

recognizes digital competence as one of the key competences for the

twenty-first century citizen (Recio Muñoz et al., 2020), and defines it as:

The confident, critical and responsible use of, and

engagement with digital technologies for learning, at work, and for

participation in society. It includes data and information literacy,

communication and collaboration, media literacy, digital content creation

(including programming), safety (including digital well-being and competences

related to cybersecurity), intellectual property related questions, problem

solving and critical thinking. (p. 9)

Assessing students’ digital competence has been a

growing concern in recent years in the area of Social Sciences and Education

(see, for example: Cabezas-González & Casillas-Martín, 2018; López-Meneses

et al., 2020; Llorent-Vaquero et al., 2020; Martínez-Piñeiro et al., 2019;

Nowak, 2019; Wild & Schulze Heuling, 2020).

To develop effective education policies that integrate

ICT into education systems and foster the development of this competence is

crucial to gain awareness of the influence that different social variables have

on its acquisition and development.

Accordingly, various research projects have been

carried out, the most frequently studied variables being gender and age. In the

context of Spain, a study on the level of digital competence of university

students concludes that men outscore women in knowledge and handling of digital

devices (Cabezas-González et al., 2017). Regarding the influence of age on the

digital competence of Spanish non-university teachers, there is evidence

suggesting that people over the age of 40 feel less competent and motivated to

use technologies in the areas of information, data literacy and educational

digital content creation (López Belmonte et al., 2020).

Research on the influence of socio-familial variables

has also been carried out. According to the study conducted in Russia by Kozlov

et al. (2019) using a sample of university students, the barriers that hold

back the development of digital competence depend on three factors:

geographical-regional, socioeconomic and personal. In Korea, Kim et al. (2018)

proved that university students who live in digitally enriched households and

school environments are more likely to engage effectively in the use of digital

technologies for learning purposes. A study conducted in Norway concluded that

family background, in terms of linguistic integration and number of books in

the household, could predict the level of digital competence of seventh-grade

students (Hatlevik et al., 2014). In Kosovo, Shala and Grajcevci (2018) found

that inclusion in academic environments, a good socioeconomic position and

living in urban as opposed to rural areas has a positive influence on the

development of this competence.

As regards the development and assessment of digital

competence, there are different standards and indicators, both for citizens and

for teachers and students: Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

(Mishra & Koehler, 2006), Krumsvik’s model (Krumsvik, 2011), Standards for

Students, a Practical Guide for Learning with Technology (ISTE, 2016), ICT

competence standards for teachers (ICT-CFT) (UNESCO, 2008), National

Educational Technology Standards for Teachers (ISTE, 2008), the European

Digital Competence Framework for Educators (DigCompEdu) (Punie, 2017), the

Common Framework for Digital Competence of Teachers (INTEF, 2017), among

others. This study follows one of the reference models of digital competence

development in Europe: The European Digital Competence Framework (DigComp).

In 2013, the European Commission published the

Framework for Developing and Understanding Digital Competence in Europe

(DigComp 1.0) (Ferrari, 2013), modified in 2016 by the European Digital

Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.0) (Vuorikari et al., 2016) and

updated in 2017 as DigComp 2.1. (Carretero et al., 2017). This model, which

encompasses a total of twenty-one digital competences, structures its

dimensions into five areas, four levels with two sublevels each, and three

domains (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Structure-dimensions

of digital competence DigComp 2.1

This research focuses on the communication and

collaboration competence area, which includes the following digital

competences: interacting through digital technologies, sharing information and

digital content, online citizen participation, collaborating through digital

technologies, netiquette, and managing digital identity.

The socio-familial variables analyzed in this study

(gender, schoolyear, family’s economic and cultural level, access to digital

devices) were defined following a review of research on the topic.

2. Methodology

The approach chosen was a quantitative methodology

(objective test and attitudes scale) with a descriptive and cross-sectional

design, since the information was gathered at one single moment during the

2018-2019 academic year.

2.1. Aims

The study pursues two main aims:

1. To learn the level of

digital competence of compulsory education students (aged 12-14) of certain

Spanish provinces in the area of communication and collaboration, taking into

account the domains of knowledge, skill and attitude.

2. To identify the

influence of socio-familial variables on these students’ development of this

competence area.

2.2. Participants

The assessment was conducted in the Autonomous

Community of Castile and León (Spain). The sampling method used was stratified

random sampling (Casal & Mateu, 2003) and the sample worked with consisted

of 807 students (668 in their last year of primary education and 139 in their

first year of compulsory secondary education) aged 12 to 14, from 18 education

centers (Table 1). From a gender-based perspective, the sample is balanced

(51.4% are girls and 48.6%, boys).

Table 1

Sample distribution

|

Total sample |

Schoolyear |

Gender |

||||||

|

Year 6 Primary

Ed. |

Year 1 Secondary

Ed. |

Female |

Male |

|||||

|

N |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

807 |

668 |

82.8 |

139 |

17.2 |

415 |

51.4 |

392 |

48.6 |

2.3. Assessment test

The assessment tool was prepared after a review of the

literature on digital competence domains, with the purpose of drawing up an

indicator model to be used as a basis for its design, and the reference model

used was DigComp 1.0. (Ferrari, 2013). Taking this model’s structure into

account, a total of 69 indicators were contemplated for the communication and

collaboration competence area, arranged into three domains (knowledge, skill

and attitude) and three levels (foundation, intermediate and advanced). These

indicators can be found in: “Modelo de indicadores para evaluar la competencia

digital de los estudiantes tomando como referencia el modelo DigComp –

Indicator Model for Assessing Students’ Digital Competence, taking the DigComp model

as a reference (INCODIES)” (García-Valcárcel et al., 2019), a more

comprehensive document that includes a total of 325 indicators related to the

five areas of digital competence.

The content of the model for this competence area was

validated using expert judge’s approach. A total of 17 experts in the design of

assessment indicators, digital competence and active professionals belonging to

different educational contexts (compulsory education, university, education

management) assessed the importance, relevance and clarity of the indicators by

means of a 4-point Likert-type scale online questionnaire (1-none, 2-little,

3-considerable, 4-great).

An item bank for this area was designed based on the

indicator model and the criteria for the creation of information gathering

tools (McMillan & Schumacher, 2005).

The battery of items was refined through peer-review,

leading to a first version of the assessment test that was used with a pilot

sample of 288 compulsory education students (including students in their 6th

year of primary education and in their 1st year of compulsory secondary

education), estimating difficulty levels of the knowledge and skill items, as

well as the reliability of the attitude ones. The results obtained were used to

produce the final test in this competence area (Table 2).

Table 2

Final structure of

the assessment test

|

Area |

Number of items

by competence domain |

Number of items

by competence level |

||||

|

Knowledge |

Skill |

Attitude |

Foundation |

Intermediate |

Advanced |

|

|

2.1. Interacting through new technologies |

1 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

2.2. Sharing information and contents |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2.3. Online citizen participation |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

2.4. Collaborating through digital channels |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

|

2.5. Netiquette |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

2.6. Managing digital identity |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

|

TOTAL A2. Communication and collaboration |

8 |

10 |

7 |

8 |

3 |

|

Knowledge and skills were assessed through an objective

test designed with questions that presented reals life situations where

students were to make decisions, choosing the correct answer among four

possible options. Attitude was approached using a previously validated

Likert-type scale that consisted of 6 items, each of them related to an

assertion on the competence area with 5 answer options (1 strongly disagree, 5

strongly agree). The final version of the test to assess students’ digital

competence in all the competence areas, known as ECODIES, is available from the

GREDOS document repository of the University of Salamanca (https://gredos.usal.es/handle/10366/139397

). Socio-familial information was gathered using a 17-item survey. After obtaining

permission from the authorities of the Educational Administration, the Ethics

Committee of the University of Salamanca, the educational centers and students’

families, the implementation of the assessment test was conducted using a

website, designed ad hoc, so that it could be easier for students to complete

it (it can be found at: https://www.ecodies.es/

). All the centers collaborated voluntarily and undertook the task of obtaining

permission from families and students, and of implementing the test during

school hours, always following the guidelines and protocols prepared by the

researchers. Once the test had been given, teachers could access a report of

their class group and one pertaining each of their students to learn their

competence level and be able to compare it with the total sample.

Regarding validity, content (theoretical framework of

reference, DigComp model) and structure (test dimensions) were considered.

Peer-review was used, the judges being 10 university teachers who were experts

in educational technology. As for structural validity, factor analysis (FA) of

principal components with Kaiser-normalized Varimax rotation was performed for

the different competence areas. The result yielded an adequate KMO value and a

highly significant Bartlett sphericity index in all cases (p<0.001)

(Casillas-Martín et al., 2020b). To test reliability, as internal consistency,

both for the entire test and for the specific knowledge, skills and attitude

tests that make it up, Cronbach’s α, α Ordinal or common factor model

(internal consistency model) (Welch & Comer, 1998), as well as Armor’s

Theta (principal-component model) were calculated. The latter are considered

more appropriate for scales consisting of fewer than five categories or for

dichotomous items. α Ordinal and Armor’s Theta were calculated based on

the tetrachoric correlations and rotated factor loads, following the

instructions provided by Domínguez-Lara (2018).

The resulting Cronbach’s α indices are below the

acceptability threshold (<.70) (Table 3). This could be due to the fact that

this statistical measure assumes the continuous nature of variables and is

considered inadequate for scales with fewer that five categories, our answers

being dichotomous (except for the attitude scale). Based on the observations of

certain authors regarding the use of this index in association with dichotomous

scales (Oliden & Zumbo, 2008; Zumbo et al., 2007), attenuation (AR) was used

to compare Cronbach’s α and α Ordinal. The values obtained were

satisfactory (>.60) and sufficient to guarantee the reliability of the

scales (Morales et al., 2003).

3. Analysis and results

As well as students’ levels of competence in the area

of communication and collaboration, it is interesting to learn whether the

influence of socio-familial variables (gender, schoolyear, family’s economic

and cultural background, access to digital devices) leads to significant

differences in the results obtained in the assessment. To avoid privacy issues

when ascertaining a family’s level of studies or profession, the “family’s

economic and cultural level” variable is defined as: family accompaniment in

the performance of school tasks, book reading in the family (outside school)

and travelling and family holidays. The “access to digital devices” variable is

defined as: student’s devices in the household (computer, tablet, music device,

Internet-enabled mobile phone, printer, e-book reader, video game console,

television). The choice of variables is based on a review of the literature on

relevant socio-familial variables in the acquisition of digital competence.

Inferential tests comparing means were performed using

SPSS v.25 software. Given the large number of subjects and once parametric

assumptions of normality had been tested (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk)

and normal distribution confirmed (>0.05), parametric tests for contrasting

hypothesis were used; specifically, Student’s t-test and ANOVA, which make the verification

of statistically significant differences possible.

Below are the main results obtained in line with the

proposed objectives.

Regarding the three domains (knowledge, skill and

attitude) of the digital communication and collaboration area, students show an

average level in knowledge and skill (=9.66). The corresponding means

were calculated by creating a variable through the sum of the knowledge and

skill competences, the possible answer range being 0 to 18. By contrast,

attitudes were highly positive, scoring a mean of 4.32 out of 5 (Table 4).

Table 3

Reliability of the

final assessment test

|

Area |

Domain |

N |

Cronbach’s α |

αordinal |

Armor’s Theta |

Attenuation Rate

(AR) |

No. elements |

|

A2 |

Knowledge-skill |

807 |

.58 |

0.70 |

0.71 |

17% |

18 |

|

Attitude |

793 |

.73 |

0.81 |

0.80 |

11% |

6 |

|

|

Competences |

N |

Cronbach α |

αordinal |

Armor’s Theta |

Attenuation Rate

(AR) |

No. elements |

|

|

A2.1. Interacting through new technologies |

807 |

.43 |

.63 |

.63 |

32% |

3 |

|

|

A2.2. Sharing information and contents |

807 |

.40 |

.60 |

.60 |

34% |

3 |

|

|

A2.3. Online citizen participation |

807 |

.33 |

.68 |

.68 |

52% |

3 |

|

|

A2.4. Collaborating through digital channels |

807 |

.24 |

.66 |

.66 |

64% |

3 |

|

|

A2.5. Netiquette |

807 |

.42 |

.72 |

.72 |

42% |

3 |

|

|

A2.6. Managing digital identity |

807 |

.21 |

.63 |

.63 |

67% |

3 |

|

|

Entire Area 2

test |

793 |

.40 |

.86 |

.86 |

19% |

24 |

Table 4

Descriptive

statistics

|

Area 2 |

N |

Min |

Max |

|

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

||

|

Y1 |

SE |

g2 |

SE |

||||||

|

Knowledge-skill (max. 18) |

807 |

0 |

17 |

9.66 |

2.98 |

-.36 |

.09 |

-.10 |

.17 |

|

Attitude (max. 5) |

793 |

0 |

5 |

4.34 |

.72 |

-2.39 |

.09 |

9.06 |

.17 |

If we focus on the data related to the influence of

socio-familial factors, as regards the gender variable, there are no

significant differences in any of the assessed domains (knowledge, skill,

attitude), nor in the data resulting from the knowledge and skill test

(Table5).

Table 5

Descriptive statistics and Student’s t-test for the

gender variable

|

Gender |

Male |

Female |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov |

Student’s

t-test |

Cohen’s

d |

|||||

|

N |

(SD) |

N |

(SD) |

Z |

gl |

p |

t |

p |

|

|

|

KN (out of 8) |

392 |

4.18

(1.61) |

415 |

4.36

(1.53) |

.13 |

607 |

.00 |

1.47 |

.14 |

.11 |

|

SK (out of 10) |

392 |

5.29

(2.05) |

415 |

5.47

(1.71) |

.12 |

577 |

.00 |

1.18 |

.24 |

.01 |

|

AT (out of 5) |

387 |

4.26

(.76) |

406 |

4.35

(.75) |

.18 |

607 |

.00 |

1.46 |

.14 |

.13 |

|

EKS (out of 18) |

387 |

9.46

(3.10) |

406 |

9.83

(2.62) |

.09 |

607 |

.00 |

1.58 |

.11 |

.12 |

Note: KN=

Knowledge, SK= Skill, AT= Attitude, EKS= Entire Knowledge-Skill Test

As for the academic year the students are in, the domains

of knowledge and skill yielded no significant differences, but that of attitude

did (<.05). The attitude of students in year 6 of primary education is more

positive (mean 4.34 against 4.10). Effect size in relation to attitude can be

regarded as between small and moderate (d=.32) (Table 6).

Table 6

Descriptive

statistics and Student’s t-test for the schoolyear variable

|

School Year |

Year

6 Primary Education |

Year

1 Compulsory Secondary

Ed. |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov |

Student’s t-test |

Cohen’s d |

|||||

|

N |

(SD) |

N |

(SD) |

Z |

gl |

p |

t |

p |

||

|

KN (out of

8) |

668 |

4.31

(1.54) |

139 |

4.06

(1.72) |

.13 |

607 |

.00 |

1.40 |

.16 |

.16 |

|

SK (out of

10) |

668 |

5.42

(1.86) |

139 |

5.18

(1.99) |

.12 |

607 |

.00 |

1.14 |

.25 |

.13 |

|

AT (out of 5) |

658 |

4.34

(.70) |

135 |

4.10

(.98) |

.18 |

112.17 |

.00 |

2.25 |

.02 |

.32 |

|

EKS(out of 18) |

658 |

9.73

(2.81) |

135 |

9.24

(3.17) |

.09 |

607 |

.00 |

1.52 |

.13 |

.17 |

Note:

KN= Knowledge, SK= Skill, AT= Attitude, EKS= Entire Knowledge-Skill Test

Regarding the family’s economic and cultural level, arranged

into four levels (very low, low, average, high), there are significant

differences (p<.05) in knowledge and skill, but not in attitude. Students

whose families’ economic and cultural level is higher are those who score the

highest in knowledge and skill. Size effect is small except in knowledge, where

it is close to moderate (Table 7).

Table 7

Descriptive

statistics and Student’s t-test for the family’s economic-cultural level

variable

|

FECL |

Very

low |

Low |

Average |

High |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov |

ANOVA |

Cohen’s

d |

||||||||||

|

N |

(DT) |

N |

(SD) |

N |

(SD) |

N |

(SD) |

Z |

gl |

p |

F |

p |

|

||||

|

KN (out of 8) |

21 |

3.91

(1.30) |

52 |

4.02

(1.49) |

379 |

4.09

(1.59) |

355 |

4.54

(1.56) |

.13 |

607 |

.00 |

4.51 |

.00 |

.30 |

|||

|

SK(out of 10) |

21 |

5.62

(1.85) |

52 |

5.30

(1.93) |

379 |

5.17 (1.94) |

355 |

5.64

(1.79) |

.12 |

607 |

.00 |

2.60 |

.05 |

.20 |

|||

|

AT (out of 5) |

20 |

3.88

(1.52) |

50 |

4.22

(.72) |

373 |

4.31

(.72) |

350 |

4.34

(.75) |

.18 |

112.17 |

.00 |

1.64 |

.18 |

.20 |

|||

|

EKS(out of 18) |

20 |

9.55

(2.42) |

50 |

9.31

(2.91) |

373 |

9.27

(2.99) |

350 |

10.16

(2.68) |

.09 |

607 |

.00 |

4.71 |

.00 |

.20 |

|||

Note.

FECL=Family’s economic-cultural level. KN= Knowledge, SK= Skill, AT= Attitude,

EKS= Entire Knowledge-Skill Test

3. Conclusions and

discussion

This study has identified the level of digital

competence in the area of communication and collaboration of compulsory

education students (aged 12-14) based on the three competence domains of

knowledge, skill and attitude. Likewise, the influence of socio-familial

variables on the development of this competence area has also been tested.

The digital level shown by students is basic in

knowledge and skill, although attitude is very positive. The results are

consistent with the findings of other studies such as the one conducted in the

Autonomous Community of Galicia (Spain) by Martínez-Piñeiro et al. (2019),

where students achieve a pass (5 out of10) in this competence area. This

situation should give cause for reflection in education centers, which should prepare

to implement curricular programs that might strengthen this type of

competences.

Moreover, it is very important to be aware of the

influence of socio-familial variables in the acquisition and development of

this competence in order to design and implement effective and compensatory

education policies. One of the purposes of this study is to contribute to such

goal.

The results obtained, as do those of other studies

(Pérez Escoda et al., 2016; Wong & Kemp, 2018), show that socio-familial

variables play an influential role in the acquisition and development of the

following digital competences: interacting through digital technologies,

sharing digital information and contents, online citizen participation,

collaborating through new technologies, netiquette, and managing digital

identity.

Hence, there is evidence that a family’s socioeconomic

level has a significant impact on the domains of knowledge and skill, but not

on attitude. Students belonging to families with high cultural and economic

levels show greater knowledge and skill in communication and collaboration.

These results corroborate the importance of this variable as a predictor of

digital competence (Ames, 2016; Claro et al., 2015). Also noteworthy is the

influence of access to digital devices, with significant differences in all the

domains (knowledge, skill, attitude). Students who have access to more devices

score higher in knowledge, skill and attitude in the competence area of

communication and collaboration. This stands in contrast with the findings of

other studies that conclude that owning and being exposed to this type of

devices does not lead to an increase in the level of digital competence (Colás

et al., 2017; Casillas-Martín & Cabezas-González, 2019).

It has not been possible to verify the impact of

gender and schoolyear (age-related) on competence level. It could be mentioned

that there are no significant differences according to gender, and as regards

school year, there are only differences in attitude that favor younger students

(primary education). Regarding gender, our results are consistent with those of

certain studies (Centeno & Cubo, 2013; Roblizo & Cózar, 2015), but

differ from those of others (Cabero et al., 2008; Cabezas-González et al.,

2017; Mayor Buzón et al., 2019; Pozo Sánchez et al., 2020) that prove the

influence of this variable. Concerning age, there is also a divergence of

results among studies and, whereas our findings are in line with those of

certain authors (García et al., 2014; Martos et al., 2016; Moreno Guerrero et

al., 2020; Rabin et al, 2020), they are different from those of others such as

Romero and Minelli (2011).

Because of the above and in the light of the findings

of this study, it may be concluded that digital competence in the area of

communication and collaboration does not depend on gender or on schoolyear

(age-related), but it is, however, associated with the economic and cultural

level and students’ families and on their access to digital devices in their

personal and household environment. The higher the economic and cultural level

and the more devices that they have access to, the greater the digital

knowledge and skill in this area.

Nevertheless, this research has certain limitations

that should be noted. The specific study variables could limit a more

all-encompassing and comprehensive explanation of the factors that influence

students’ level of digital competence. Likewise, the validation of the model

could be complemented by performing a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

To finish, future lines of research could be aimed at

studying the relationships and incidence between the digital competence level

of school students in age ranges other than the ones analyzed and other

personal, social and family-related characteristics (variables) different from

the ones used in this study. Moreover, it would be interesting and relevant to

propose other supplementary assessment strategies to objectively verify these

students’ digital competence. All of the preceding would enrich and complete

this line of research. It would also be highly advisable to replicate this work

at the present time, after the lockdown situation led to by the COVID-19

pandemic, which made it necessary to resort to the use of technological devices

to be able to continue from home the teaching and learning processes that had

begun in Spanish school centers in academic year 2019-2020. It would be very

useful to check whether, after the experience, school students’ competence

level has changed and also analyze the impact of socio-familial variables on

their competence level. This would help to guide policies designed for the

integration of ICT in teaching centers.

Funding

This study is part of the “Evaluación de la

competencia digital de los estudiantes de educación obligatoria y estudio de la

incidencia de variables sociofamiliares – Assessment of the digital competence

of compulsory education students and study of the incidence of socio-familial

variables (EVADISO)” R&D project, funded by the Ministry of Economy and

Competitiveness within the Excellence State Program for the Fostering of

Scientific and Technological Research of the Spanish Government (EVADISO,

EDU2015-67975-C3-3-P, MINECO/FEDER).

References

Ames

P. (2016). Los niños y sus relaciones con las tecnologías de información y comunicación:

un estudio en escuelas peruanas. DESIDADES - Revista Eletrônica de Divulgação Científica Da Infância

E Juventude, 11, 11-21. https://bit.ly/3kiPph0

Cabero,

J., Llorente, M.C., & Puentes, A. (2008). Alfabetización Digital: Un

estudio en la Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra. Fortic.

Cabezas-González

M., & Casillas-Martín, S. (2018). Social Educators: A Study of Digital

Competence from a Gender Differences Perspective. Croatian Journal of

Education, 20(1), 11-42. https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v20i1.2632

Cabezas-González,

M., Casillas-Martín, S., Sanches-Ferreira, M., & Teixeira-Diogo, L.F.

(2017). Do Gender

and Age Affect the Level of Digital Competence? A Study with University

Students. Fonseca Journal of Communication, 15, 109-125. http://dx.doi.org/10.14201/fjc201715109125.

Carretero,

S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie,

Y (2017). DigComp 2.1. The digital competence framework for citizens. Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/38842

Casal, J.,

& Mateu, E. (2003). Tipos de muestreo. Rev. Epidem. Med. Prev, 1(1), 3-7. https://www.coursehero.com/file/9890875/TiposMuestreo1/

Casillas-Martín

S., & Cabezas González, M. (2019). Are early childhood education teachers prepared for

educating in the network society? Opción,

35(89-2), 1317-1348. https://bit.ly/3mm0Hmv

Casillas-Martín,

S., Cabezas-González, M., & García-Peñalvo, F.J. (2020a). Digital competence of early childhood education

teachers: attitude, knowledge and use of ICT. European

Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 210-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2019.1681393

Casillas-Martín,

S., Cabezas-González, M., & García-Valcárcel

Muñoz-Repiso, A (2020b). Psychometric analysis of a

test to assess the digital competence of compulsory education students. RELIEVE,

Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa,

26(2), art. 2. http://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.26.2.17611

Centeno

G., & Cubo, S. (2013). Evaluación de la competencia digital y las actitudes

hacia las TIC del alumnado universitario. Revista de Investigación Educativa,

31(2), 517-536. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/rie.31.2.169271

Cho,

H., Song, C., & Adams, D. (2020). Efficacy and Mediators of a Web-Based Media Literacy

Intervention for Indoor Tanning Prevention. Journal of Health Communication,

25(2), 105-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1712500

Claro, M.,

Cabello, T., San Martín, E., & Nussbaum, M. (2015). Comparing marginal

effects of Chilean students’economic, social and

cultural status on digital versus reading and mathematics performance. Computers

and Education, 82, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.018

Colás, P.,

Conde, J., & Reyes, S. (2017). Digital competences of non-university

students. RELATEC. Revista Latinoamericana de

Tecnología Educativa, 16(1), 7-20. https://doi.org/10.17398/1695-288X.16.1.7

De

La Fuente Prieto, J., Lacasa Díaz, P., & Martínez-Borda, R. (2019).

Adolescentes, redes sociales y universos transmedia:

La alfabetización mediática en contextos participativos. Revista Latina de

Comunicación Social, 74, 172-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1326

Domínguez-Lara,

S. (2018). Fiabilidad y alfa ordinal. Actas Urológicas Españolas, 42(2),

140-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuro.2017.07.002

Ferrari, A.

(2013). DigComp: A framework for developing

and understanding digital competence in Europe. Publications Office of

the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2788/52966

García

Valcárcel, A., Hernández Martín, A., Mena Marcos, J.J., Iglesias Rodríguez.,

A., Casillas-Martín, S., Cabezas-González, M., González Rodero, L.M., Martín

del Pozo, M., & Basilotta Gómez-Pablos, V.

(2019). Modelo de indicadores para evaluar la competencia digital de los

estudiantes tomando como referencia el modelo DIGCOMP (INCODIES). https://gredos.usal.es/handle/10366/139409.

García,

R., Ramírez, A., & Rodríguez, M.M. (2014). Educación en alfabetización

mediática para una nueva ciudadanía prosumidora. Comunicar, 22(43),

15-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-01

González-Fernández,

N., García, A.R., & Gómez I.A. (2019). Media literacy in family stages. Diagnosis, requirements and training proposal. Education in the

Knowledge Society, 20, 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.14201/eks2019_20_a11

Gutiérrez

Castillo, J.J., Cabero Almenara, J., & Estrada Vidal, L.I. (2017). Diseño y

validación de un instrumento de evaluación de la competencia digital del

estudiante universitario. Revista Espacios, 38(10), 1-27. https://idus.us.es/handle/11441/54725

Hatlevik,

O.E., Ottestad, G., & Throndsent,

I. (2014). Predictors

of digital competence in 7th grade: a multilevel analysis. Journal of

Computer Assisted Learning, 31, 220-231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12065

Holguin-Alvarez,

J., Manrique-Alvarez, G., Apaza-Quispe, J., & Romero-Hermoza, R. (2020).

Digital competences in the social media program for older adults in vulnerable

contexts. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, 9(5),

228-232. http://www.ijstr.org/paper-references.php?ref=IJSTR-0620-36916

INTEF

(2017). Marco común de la competencia digital docente. http://bit.ly/37pk5Xg

ISTE (2008).

ISTE Standards for Teachers. NETBO2.

ISTE (2016).

ISTE Standards for Students. A Practical Guide for Learning with Technology.

Stanstebook.

Ivanovich,

P.V., Vladimirovich, K.O., Anatolievich, G.A.,

Sergeevich, G.A., Ivanovich, S.V., Nashatovna, M.V.,

& Vladimirovna, Y.N. (2020). Digital literacy and digital didactics for the

development of new learning models. Revista Opción,

36(27), 357-1376. https://produccioncientificaluz.org/index.php/opcion/article/view/32046

Kim, H.J.,

Hong, A.J., & Song, H.D. (2018). The relationships of

family, perceived digital competence and attitude, and learning agility

in sustainable student engagement in higher education. Sustainability,

10, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124635

Kozlov, A., Kankovskaya, A., Teslya, A.,

& Zharov, V. (2019). Comparative study of

socio-economic barriers to development of digital competences during formation

of human capital in Russian Arctic. IOP Conference Series: Earth and

Environmental Science, 302, 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/302/1/0121252019

Krumsvik, R.J. (2011). Digital competence in Norwegian teacher

education and schools. Högre Utbildning, 1(1), 39-51. https://hogreutbildning.se/index.php/hu/article/view/874

López

Belmonte, J., Pozo Sánchez, S., Vázquez Cano, E., & López Meneses, E.J.

(2020). Análisis de la incidencia de la edad en la competencia digital del

profesorado preuniversitario español. Revista Fuentes, 22(1),

75-87. https://doi.org/10.12795/revistafuentes.2020.v22.i1.07

López-Meneses,

E., Sirignano, F.M., Vázquez-Cano, E., &

Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M. (2020). University

students' digital competence in three areas of the DigCom

2.1 model: A comparative study at three European universities. Australasian

Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 69-88. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5583

Llorent-Vaquero, M., Tallón-Rosales, S., & De las Heras

Monastero, B. (2020). Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs)

in Communication and Collaboration: A Comparative Study between University

Students from Spain and Italy. Sustainability,

12, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12103969

Martínez-Piñeiro,

E., Gewerc, A., & Rodríguez-Gobra,

A. (2019). Nivel de competencia digital del alumnado de educación primaria en

Galicia. La influencia sociofamiliar. RED. Revista de Educación a Distancia,