Evaluar el uso de las redes sociales de lectura en la

educación literaria en contextos formales e informales. Diseño y validación de

la herramienta RESOLEC

To evaluate the use of social reading networks in literary education in formal and informal contexts. Design and

validation of the RESOLEC tool

Dña. Lucía Hernández Heras. Personal Investigador en Formación. Universidad de Zaragoza.

España.

Dña. Lucía Hernández Heras. Personal Investigador en Formación. Universidad de Zaragoza.

España.

Dra. Diana Muela Bermejo. Profesora Contratada Doctor. Universidad

de Zaragoza. España.

Dra. Diana Muela Bermejo. Profesora Contratada Doctor. Universidad

de Zaragoza. España.

Dra. Rosa Tabernero Sala. Profesora Titular de Universidad.

Universidad de Zaragoza. España.

Dra. Rosa Tabernero Sala. Profesora Titular de Universidad.

Universidad de Zaragoza. España.

Recibido:

2022/03/16 Revisado 2022/03/19 Aceptado: 2022/04/19 Preprint: 2022/04/29 Publicado: 2022/05/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Hernández-Heras, L., Muela-Bermejo,

D., & Tabernero-Sala, R. (2022). Evaluar el uso de las redes sociales de

lectura en la educación literaria en contextos formales e informales. Diseño y

validación de la herramienta RESOLEC [To evaluate the use of social reading networks in literary education in formal and informal contexts. Design and validation of the

RESOLEC tool]. Pixel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, 64, 139-164. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.93831

RESUMEN

Con la aparición de las

redes sociales de lectura, los usuarios pueden interactuar entre iguales en

torno a una misma afinidad, convirtiendo la lección en una práctica dominada

por la cultura participativa. Ante la atención que están recibiendo estas

plataformas, se ha diseñado y validado la herramienta RESOLEC, con la que se

pretende ofrecer a los docentes de Secundaria y Bachillerato un instrumento

validado que les permita evaluar la capacidad de estas redes para fomentar el

aprendizaje informal y la educación literaria. Para crear la batería de

indicadores, nos fundamentamos en la Teoría de la Actividad y en el paradigma

de la educación literaria. Para validarla, emprendimos una prueba de jueces

expertos y una prueba piloto con una muestra aleatoria de 10 redes sociales.

Tras la aplicación de las pruebas y estadísticos correspondientes, se

reformularon 10 indicadores y se suprimieron 2 y todas las dimensiones se se consideraron idóneas. 52 ítems, agrupados en dos escalas

de 3 y 4 dimensiones respectivamente, integran el instrumento definitivo.

ABSTRACT

With the emergence of social reading

networks, users can interact among peers around the same affinity, turning the

lesson into a practice dominated by participatory culture. Given the attention

that these platforms are receiving, the RESOLEC tool has been designed and

validated, with the aim of offering Secondary and Baccalaureate teachers a

validated instrument that allows them to evaluate the capacity of these

networks to promote informal learning and literary education. To create the

battery of indicators, we drew on Activity Theory and the literary education

paradigm. To validate it, we undertook an expert judge test and a pilot test

with a random sample of 10 social networks. After the application of the

corresponding tests and statistics, 10 indicators were reformulated and 2 were

deleted, and all dimensions were considered suitable. 52 items, grouped into

two scales of 3 and 4 dimensions respectively, make up the final instrument.

PALABRAS CLAVES · KEYWORDS

Redes sociales; lectura; literatura; aprendizaje

informal; web

Social networking; reading; literature; informal

learning; web

.

1. Introducción

Las

redes sociales se han convertido en el espacio de socialización predilecto de

los jóvenes para entablar contacto personal con sus iguales (Calvo & San

Fabián, 2018). Registradas como las páginas webs con más visitas, su uso

destaca sobre todo entre el público adolescente (Capilla & Cubo, 2017).

Ante este éxito, numerosas investigaciones han subrayado su potencial didáctico

(Ferreira-Borges & França-Teles, 2019; Figueras-Maz et al., 2021) en busca de nuevos recursos que atraigan

la atención del joven alumnado. No obstante, como recuerdan Valencia et al.

(2020) en su revisión sistemática, existe cierta homogeneidad en los métodos

escogidos para explorar el uso de estas redes en contextos educativos, ya que

una gran proporción de los académicos recurren al cuestionario.

Entre

las plataformas que oferta esta nueva ecología mediática (Scolari,

2017), han aparecido las redes sociales de lectura, en las que los usuarios se

registran voluntariamente (Lluch, 2014) para compartir su afición por la

literatura (De Amo, 2019). En todas las actividades que impulsan redes como Goodreads o Lecturalia, la

lección es el motivo que suscita la conversación social (Borrás, 2010), por lo

que se actualizan las características de los clubes de lectura clásicos

mediante las funcionalidades que ofrece la web 2.0 (Asadi

et al., 2017). De esta forma, los lectores hacen públicos y valoran los títulos

que ya han concluido, reflexionan sobre sus experiencias lectoras, pueden crear

grupos de discusión, configurar su perfil lector personal o marcarse futuros

objetivos de lectura (Sánchez-García et al., 2021). Así, generan un ambiente de

colaboración y reciprocidad (Moody, 2019) que define

todas las etapas: desde la selección de un texto hasta la evaluación final

(García-Roca, 2020). Consecuentemente, la interfaz se convierte en un lugar de

pertenencia (Lluch, 2014), donde los usuarios buscan integrarse en la comunidad

y ser aceptados como miembros (Ramos & Oliva, 2018).

Ante

la atención que están recibiendo estos paratextos por parte de los lectores y

su influencia como modelos de mediación cultural (Sánchez García et al. 2021),

la literatura académica recomienda la selección de indicadores que sirvan para

evaluar su calidad y su efectividad (Lluch et al., 2015), aunque esta práctica

investigadora haya sido poco habitual. Si bien se han emprendido estudios que

sondean los beneficios de estas redes para el fomento de la lectura o del

aprendizaje (Lluch, 2014; García-Roca, 2020; 2021), en ninguno de estos

trabajos se ha diseñado una herramienta que evaluara el desempeño de estas

redes para la educación literaria o el aprendizaje informal. De hecho, los

métodos seleccionados por estos estudios oscilan desde la encuesta (García

Roca, 2020; Thelwall & Kousha,

2017) hasta el análisis de contenido (Montesi, 2015; Driscoll & Rehberg, 2018; Moody, 2019) pasando por estudios bibliométricos (Piryani et al., 2018; Thelwall,

2019; Kadiresan et al., 2020).

No

obstante, corresponde reseñar dos investigaciones: la primera, de Moradi & Safavi (2013), en la

que los autores crearon una parrilla de 49 indicadores agrupados en 8

dimensiones (perfil, privacidad, capacidad de la red social, búsqueda de

membresía, de libros, información técnica y estatus del libro). Por otra parte,

la de Asadi et. al (2017), que agrega una rúbrica de

35 indicadores agrupados en 9 dimensiones (cuestiones de seguridad y

privacidad, propiedades demográficas, perfiles, interacción, búsqueda de

amigos, ayuda técnica, búsqueda de libros, grupos y corpus). A diferencia del

instrumento que a continuación se propone, creado con fines educativos, las

rúbricas presentadas en ambos artículos incorporan indicadores cuya

arquitectura se basa en criterios webométricos para

explorar el diseño y la estructura de este tipo de redes desde un enfoque

técnico y comunicativo.

Así

pues, el presente estudio tiene como objetivo diseñar y validar un instrumento

que permita a los docentes evaluar la potencialidad de las redes sociales de

lectura para el desarrollo del aprendizaje informal y la educación literaria.

De esta forma, se pretende ofrecer nuevas herramientas que establezcan puentes

entre el aprendizaje formal, informal y no formal, como reclama la

investigación (Davies, 2017). Para crear la batería de indicadores, nos hemos

fundamentado en la Teoría de la Actividad y el paradigma de la educación

literaria. Se han seleccionado estos constructos para examinar qué se está

aprendiendo, tanto en términos didácticos, como literarios; en estos servicios

cada vez más populares.

1.1 La Teoría de la Actividad aplicada a las redes

sociales

La

Teoría de la Actividad (TA) posibilita el examen del ejercicio individual y

colectivo mediado por un artefacto en un contexto dado (Kuutti,

1996), puesto que asume que el aprendizaje deriva del intercambio social y

cultural de los individuos en prácticas colectivas. Ideada por Leont’ev (1974) y Engeström

(1987), ha sido aplicada como andamiaje teórico en distintos entornos de

aprendizaje relacionados con el empleo de tecnologías digitales, tanto en

contextos formales (Lim & Hang, 2003; Collis & Magaryan, 2004) como

de aprendizaje informal (Park et al., 2011; Heo &

Lee, 2013; Jiménez Cortés, 2019). En estos estudios, las TIC promueven la

creación de redes de aprendizaje que bonifican a los miembros con la

adquisición de conocimiento, la reflexión sobre la propia experiencia o el

desarrollo de la identidad.

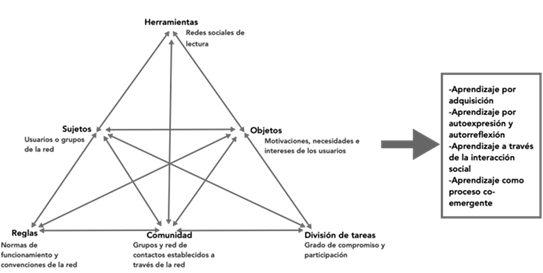

Para

que estos objetivos lleguen a término, la actividad se ordena como un complejo

sistema triangular de iteraciones entre seis componentes. En el caso de la

actividad de los usuarios en las redes sociales de lectura (fig. 1), los

sujetos son los individuos o subgrupos que participan en ellas, las cuales se

desempeñan como las herramientas mediadoras del aprendizaje que configuran el

espacio de interacción. Los objetos están constituidos por las motivaciones,

necesidades y los intereses de los usuarios, en este caso, vinculados a la

experiencia lectora. Su participación depende de la organización de las tareas

y la adopción de diferentes roles y compromisos adquiridos con la comunidad,

organizada a través de grupos y de una extensa red de contactos, cuya

estabilidad se regula mediante las convenciones y normas impuestas por las

mismas redes.

Park

et al., (2011) concretan, a partir de Fenwick & Tennant (2004), el output que produce el funcionamiento

sincrónico de este sistema:

·

Aprendizaje por adquisición: se da cuando los

individuos obtienen nuevas habilidades y conocimientos especializados a través

de la lectura y la recepción, sin que adopten una postura proactiva con la que

contribuyan a la creación de nuevos contenidos.

·

Aprendizaje por autorreflexión y autoexpresión: se alcanza

cuando los usuarios participan en la creación colectiva de significado al

transformar el conocimiento existente u originar uno nuevo, mientras

reflexionan en términos de contenido (qué aprendió) o proceso (cómo).

·

Aprendizaje a través de la interacción social y el

compromiso activo con la comunidad: es posible en la medida en que los sujetos,

como participantes de pleno derecho, actúan a todos los niveles del colectivo.

El conocimiento se crea a partir de la comunicación con los otros mediante vínculos

de cooperación, intercambio y negociación, que pueden revertir en una identidad

individual o grupal acrisolada.

·

Aprendizaje como proceso co-emergente:

tiene lugar cuando los sistemas de aprendizaje y los participantes se adaptan,

organizan y transforman simultáneamente.

Figura 1

Modelo tetrafactorial

1.2 La educación literaria

Actualmente,

la labor de la educación literaria halla su razón de ser en la formación de

lectores competentes (Tabernero, 2005). En este sentido, Colomer (1996)

identifica los dos objetivos fundamentales de la educación literaria: la

formación de la competencia interpretativa y la construcción de hábitos

lectores que fomenten una relación placentera y de compromiso personal con las

lecturas. Estos propósitos se encaminan a generar “engaged

readers”: lectores intrínsecamente motivados que

emplean sus herramientas cognitivas para decodificar e interpretar y aplican lo

que leen en contextos personales, sociales e intelectuales (Gambrell,

2011).

Para

lograrlo, en cuanto a la mejora de la competencia interpretativa, se precisan

la adquisición de saberes que permitan leer e interpretar los textos (Mendoza,

1998), cierto dominio del metalenguaje disciplinar (Langer, 1995) y de la

intertextualidad y conocimientos sobre el contexto de las obras (Colomer,

2005). En este cometido, el mediador ha de abogar por la lectura conjunta,

otorgándole libertad al lector, pero guiándole en el proceso de interpretación

(Sanjuán, 2013). En cuanto a la labor de la mediación en el fortalecimiento de

hábitos lectores, la literatura académica propone la utilización de diversas

prácticas, como el juego (Chou et al., 2016), el contacto con los autores,

editores y bibliotecas (Patte, 2011) y la vinculación

del hecho lector con la escritura (Alvarado, 2013). Langer (1995) añade la

importancia de que el receptor tenga la autonomía de construir su autoimagen

como lector.

La

progresiva renovación que ha experimentado la educación literaria ha puesto el

foco en la discusión literaria, basada en la conversación entre iguales para

compartir pensamientos y experiencias y “co-generar”

el sentido del texto (López Valero et al., 2021). No obstante, aunque se

aconseja que los lectores gocen de autonomía para dinamizar la discusión, es

precisa la aportación de un mediador (Munita, 2021) que incluya el

planteamiento de preguntas que trasciendan de lo más genérico a lo más

específico y que adapte el formato de la discusión a la especifidad

de los textos (Chambers, 2007).

Cabe

subrayar la importancia que atesora el corpus en la educación literaria, que

debe ser extenso y variado, aunque su selección ha de acogerse a unos criterios

concretos basados en la calidad, la variedad temática y los intereses de los

lectores (Colomer, 2005). Así, los profesores que emprenden actividades basadas

en las elecciones individuales de los estudiantes contribuyen a reforzar su

autonomía y su sensación de control (Jang et al.,

2010) A pesar de que el corpus debe contar con las filias de los lectores para

su estructuración, el mediador tiene que incluir igualmente obras que aporten

beneficios a los destinatarios (Margallo, 2012): como sintetiza Gambrell (2011), una característica de una instrucción de

lectura efectiva es aquella en la que se ofrecen lecturas que hagan progresar

al estudiante; más que abrumarlo.

2. Metodología

El estudio pretende diseñar y

validar un instrumento que permita a los docentes de Secundaria y Bachillerato evaluar

la capacidad de las redes sociales de lectura para fomentar el aprendizaje

informal y la educación literaria, con el objeto de que puedan incorporarlas en

su práctica docente (Watlington, 2011). Enmarcados en

este gran propósito, los objetivos específicos de la investigación son los

siguientes:

1.

Identificar y establecer los

constructos de estudio en varias dimensiones y extrapolarlas al instrumento a

través de diferentes indicadores.

2.

Validar el contenido de la

herramienta por medio de una prueba de jueces expertos.

3.

Validar su fiabilidad a través

de una prueba piloto en la que se aplique la herramienta en el análisis de una

muestra aleatoria de redes sociales de lectura.

2.2 Procedimiento. Participantes y técnicas de

análisis de los datos

Fase 1: construcción del

instrumento

Para diseñar la herramienta se

llevó a cabo una revisión bibliográfica. Este proceso condujo a una primera

versión de RESOLEC, instrumento formado por dos escalas; la primera compuesta

por 3 dimensiones y la segunda por 4. Esta herramienta de evaluación constaba

de 54 indicadores, que en su aplicación serían evaluados mediante una escala

Likert del 1 al 4, donde 1= nada; 2= poco; 3= bastante; 4=mucho. Los dos

constructos de los que surgen las dos escalas son la Teoría de la Actividad

aplicada a las redes sociales y la educación literaria, respectivamente.

Con el objeto de analizar la

potencialidad de estas redes para el aprendizaje informal, la presente

investigación ha partido de las dimensiones validadas por Fenwick

& Tennant (2004), Park et al. (2011) y Jiménez

Cortés (2019): 1) aprendizaje por adquisición, 2) aprendizaje por

autorreflexión y autoexpresión, 3) aprendizaje a través de la interacción

social y el compromiso activo con la comunidad, 4) aprendizaje como proceso co-emergente. No obstante, solo las tres primeras han sido

adaptadas para el estudio en cuestión por su pertinencia y ajuste a los

objetivos fijados por las investigadoras. Puesto que estas dimensiones solo

habían sido adoptadas para el diseño de cuestionarios destinados a usuarios de

redes sociales, ha sido necesaria su reformulación. De esta forma, los ítems

pretenden medir la capacidad de las redes para fomentar los tres tipos de

aprendizaje. En la medida de lo posible, se ha intentado reelaborar indicadores

ya validados. En concreto, se han adaptado los ítems 1, 7, 12, 13 y 15 de la

investigación de Jiménez Cortés (2019).

Por su parte, para la

configuración de las dimensiones del bloque de educación literaria, se han

seleccionado:

·

El desarrollo de la competencia

interpretativa y 2) la construcción de hábitos lectores como una relación

placentera y de compromiso personal con las obras. Ambas dimensiones se

corresponden, por tanto, con los dos objetivos específicos asociados a la

formación literaria según la bibliografía académica (Colomer, 1996).

·

La discusión literaria. Esta

dimensión se corresponde uno de los “géneros disciplinares” (Dias-Chiaruttini, 2014) más destacados de la educación

literaria y que adquiere protagonismo en estas redes puesto que habilitan

espacios para el diálogo y el debate.

·

El corpus, así como sobre los

criterios para su selección (Colomer, 2005). Esta dimensión se corresponde con

un aspecto central en las redes sociales de lectura, dadas las amplias bases de

libros que albergan.

Fase 2: Refinado del

instrumento inicial

Para validar el contenido y la

confiabilidad del instrumento (Escobar-Pérez & Cuervo-Martínez, 2008), se

emprendió una prueba de jueces expertos con el objeto de analizar en qué medida

los ítems elaborados eran representativos de los constructos de estudio (Beck

& Gable, 2001). La elección de los participantes

fue deliberada en función de unos criterios de inclusión establecidos por las

investigadoras (Rodríguez et al., 1996). Se integró a expertos familiarizados

con la construcción y la adaptación de instrumentos y a jueces especializados

no tanto en el ámbito psicométrico como en el constructo

de interés o con experiencia en la disciplina de la que forman parte (Davis,

1992). De esta forma, cooperaron 8 expertos de las ramas de comunicación,

educación y de didáctica de la literatura (tabla 1). Además, todos los

participantes disponían de una cuenta personal en alguna red social.

Perfil profesional de

los jueces expertos

|

Titulación |

Puesto de trabajo |

Experiencia en métodos de medición |

|

Comunicación Audiovisual |

Profesor titular del Área

de Periodismo |

Sí |

|

Periodismo |

Encargada de Marketing y

Comunicación |

No |

|

Periodismo |

Encargada de Marketing

Digital y Ecommerce |

No |

|

Filología Hispánica |

Profesora Contratado Doctor

del Área de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura |

Sí |

|

Filología Hispánica |

Profesor titular del área

de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura |

Sí |

|

Filología Hispánica |

Profesora Ayudante Doctor

del Área de Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura |

Sí |

|

Magisterio de Educación

Infantil |

Profesor Contratado Doctor

en Educación |

Sí |

|

Magisterio de Educación

Primaria |

Profesora Contratado Doctor

en Educación |

Sí |

La plantilla que cumplimentaron

los expertos, según las indicaciones de Delgado-Rico et al. (2012), incluía:

las instrucciones de la prueba, la definición de ambos constructos y sus

características, una tabla recopilatoria de los datos personales y

profesionales de los jueces, la batería de indicadores y una parrilla de cinco

categorías para que los expertos evaluaran cuantitativamente la claridad,

coherencia y relevancia de los ítems y la suficiencia e idoneidad de las

dimensiones a través de una escala Likert, donde 1=Muy inadecuado;

2=Inadecuado; 3=Adecuado; 4=Muy adecuado. Asimismo, se habilitaron varios

espacios para que el experto pudiera adjuntar valoraciones de carácter

cualitativo.

El análisis de los datos se

llevó a cabo mediante varios procedimientos, utilizando Microsoft Excel y Stadistical Package for the Social Sciences: en primer lugar, se calculó la media y la

desviación típica de los ítems en las categorías de “claridad”, “coherencia” y

“relevancia” y de las dimensiones en cuanto a su “suficiencia” e “idoneidad”.

Los ítems que no alcanzaron una puntuación media ≥ 3 en “coherencia” y

“relevancia” fueron eliminados, mientras que aquellos indicadores que

obtuvieron una valoración media por debajo del parámetro de “adecuado” en la

categoría de “claridad” fueron reformulados. Posteriormente, para medir qué

ítems fueron catalogados como adecuados por los expertos desde el punto de

vista del contenido (McGartland et al., 2003), se

aplicó el Content Validity Ratio (McGartland

et al, 2003), para escalas ordinales. El CVI de cada ítem se calculó dividiendo

el cómputo de jueces que lo habían valorado con un 3 o 4 entre número total de

jueces. En cuanto a su interpretación, aquellos indicadores que alcanzaron un

índice >.80 en todas las categorías fueron considerados como válidos.

Finalmente, se midió el coeficiente de Kendall con el propósito de calibrar la

confiabilidad inter- observador (Bao et al., 2009),

con un rango de 0 a 1 donde el valor 1 representa el nivel de concordancia

total y 0 el desacuerdo total (Dorantes-Nova et al., 2016).

Fase 3: prueba piloto

Antes de emprender la prueba

piloto, se diseñó una rúbrica analítica para orientar la evaluación de los observadores

con base en unos criterios objetivables y fundamentados a partir de la lectura

de la bibliografía académica y la observación de las websites.

Puesto que es imposible adjuntar la rúbrica completa por razones de espacio,

adjuntamos como ejemplo los descriptores que se han establecido para la

valoración de uno los ítems (tabla 2).

Pequeña muestra de la

rúbrica analítica

|

Ítem |

1=Nada |

2=Poco |

3=Bastante |

4=Mucho |

|

Permite

al usuario valorar las creaciones de otros miembros |

Nunca |

Permite

al usuario valorar cualitativamente las creaciones de otros miembros |

Permite

al usuario valorar cualitativamente las creaciones de otros miembros y a

través del like |

Permite

al usuario valorar cualitativamente las creaciones de otros miembros y a

través de like

y dislike |

A continuación, aleatoriamente

se seleccionó una muestra de 10 aplicaciones de un universo de 24, cuya selección

se había supeditado a los siguientes requisitos: su gratuidad en todos los

espacios de la web, su accesibilidad online y, por último, el objetivo concreto

de su configuración: la lectura en red. En el compendio de las redes del

estudio piloto se ha intentado, además, aglutinar webs cuyas interfaces se

ofrecen en distintos idiomas. Así, se han analizado 4 redes inglesas, 2

francesas, 2 españolas y 2 alemanas.

Dos observadores previamente

entrenados se dispusieron a evaluar las aplicaciones mediante la batería de

ítems. Para comparar la concordancia de sus evaluaciones, se optó por el

estadístico Kappa de Cohen (1960), según el cual comienza a haber un acuerdo

moderado a partir de .41. Para asegurar la consistencia interna del sistema de

indicadores se aplicó a la escala completa el Alpha de Cronbach, teniendo en

cuenta que cuanto más próximo esté el coeficiente al 1, más consistentes serán

los ítems entre sí (Hernández Sampieri et al., 2006).

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1 Refinado del instrumento inicial

Tras la cumplimentación del formulario de evaluación

por parte de los jueces y el cálculo de la media, la desviación típica y el IVC

de cada ítem (tabla 3), se realizaron varias modificaciones –enunciadas entre

paréntesis–, teniendo en cuenta las valoraciones cualitativas y cuantitativas

emitidas por los expertos.

Tabla 3

Media, desviación típica e ICV de los ítems con M<3 en las categorías

de claridad, coherencia o relevancia

|

Ítem |

Claridad |

Coherencia |

Relevancia |

|||||||

|

M |

DT |

ICV |

M |

DT |

ICV |

M |

DT |

ICV |

|

|

|

Escala 1: aprendizaje informal |

||||||||||

|

1.2. Introduce contenidos propios a través de

entradas realizadas por los trabajadores de la red social |

2 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

1.3. Censura contenidos inaceptables o incorrectos |

2.5 |

.535 |

.625 |

3.38 |

.518 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

1.4. Contribuye a desarrollar la experiencia del

usuario en distintas áreas |

2.63 |

.518 |

.75 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2.5. Habilita espacios de debate |

2.63 |

.518 |

.75 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2.6. Incluye medios para que el usuario denuncie

contenidos que considera abusivos u ofensivos |

2.13 |

.641 |

.25 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

|

|

3.8. Permite la promoción social de los usuarios dentro

de una jerarquía impuesta por la propia red |

2.5 |

.535 |

.625 |

3.5 |

.535 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Escala 2: educación literaria |

||||||||||

|

4.3. Emplea conceptos del sistema literario |

2.88 |

.354 |

.75 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

|

|

4.6. Los procesos de etiquetación responden a

criterios literarios |

2.88 |

.354 |

.875 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

|

|

7.2. Impone criterios de inclusión para la

selección de las obras |

2.88 |

.354 |

.75 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

7.4. Guía al lector en la elección de los textos

proponiendo obras completamente distintas a sus intereses para ampliar sus

horizontes literarios |

2.13 |

.354 |

.25 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

Por su baja puntuación (<3 en media y <.81 en ICV)

en la categoría de claridad, se reelaboraron los ítems 1.2 (“incorpora

publicaciones propias“), 1.3 (“corrige los contenidos que han sido realizados

por los usuarios si son incorrectos“) y 4.6 (“revisa las etiquetas asignadas a

la descripción de la obra si son incorrectas”); se simplificó la redacción de

los indicadores 1.4 (“permite al usuario mejorar su experiencia en distintas

áreas”), 2.6 (“incluye medios para que el usuario denuncie contenidos que

considera abusivos”), 7.2 (“impone criterios para la selección de las obras”) y

7.4 ("guía al lector en la elección de los textos proponiendo obras

completamente distintas a sus intereses“) se concretaron los ítems 2.5

(“habilita espacios de discusión”), 3.8 (“permite la ascensión social de los

usuarios dentro de una jerarquía impuesta por la propia red”) y 4.3 (“emplea

con pertinencia conceptos del sistema literario”) y se suprimió el 5.3 por

obtener puntuaciones <3 en coherencia y relevancia y <.81 en ICV. Además,

a todos los ítems se les añadió el sujeto del enunciado por recomendación de

uno de los expertos. Incluso con los bajos índices de los ítems señalados, el

contenido del instrumento es adecuado puesto que ICV= .90 en claridad, ICV=.98

en coherencia y relevancia.

Como demuestra la tabla 4, todas las dimensiones se

consideraron idóneas, así como los ítems que las integran se consideraron

suficientes para medir cada una de ellas.

En relación con el grado de acuerdo entre los jueces

(tabla 5), existe significación estadística en cuanto a las características de

claridad, coherencia y relevancia en todas las dimensiones, con un acuerdo alto

en las dimensiones 1 y 7 en cuanto a claridad y un acuerdo bajo en la dimensión

6 con respecto a coherencia. En general, el grado de acuerdo entre los jueces

es moderado-alto. Con respecto a la concordancia entre expertos en cada

categoría del instrumento global, también se da una significación estadística

(ρ<.05), con un grado de acuerdo de .744 en claridad; .672 en coherenia; .682 en relevancia; .625 en idoneidad y .567 en

suficiencia.

Media y desviación

típica por dimensiones

|

Dimensión |

Suficiencia |

Idoneidad |

||

|

M |

DT |

M |

DT |

|

|

1. Aprendizaje por adquisición |

3.88 |

.354 |

4 |

0 |

|

2. Aprendizaje por autorreflexión y autoexpresión |

3.38 |

.518 |

3.38 |

.518 |

|

3. Aprendizaje a través de la interacción social y

el compromiso activo con la comunidad |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

4. Competencia interpretativa |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

5. Construcción de hábitos lectores como una

relación placentera y de compromiso personal con las obras |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

6. Discusión literaria |

3.38 |

.518 |

4 |

0 |

|

7. Corpus |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

Coeficientes de Kendall

y significación estadística de las dimensiones del instrumento de medida

|

Dimensiones |

Claridad |

Coherencia |

Relevancia |

|||

|

Coeficiente Kendall |

|

Coeficiente Kendall |

|

Coeficiente Kendall |

|

|

|

D1 |

.933 |

.000 |

.625 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

|

D2 |

.883 |

.000 |

.845 |

.000 |

.611 |

.000 |

|

D3 |

.733 |

.000 |

.614 |

.000 |

.506 |

.000 |

|

D4 |

.764 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

|

D5 |

.717 |

.000 |

.743 |

.000 |

.824 |

.000 |

|

D6 |

.759 |

.000 |

.500 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

|

D7 |

.852 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

.679 |

.000 |

3.1 Prueba piloto

RESOLEC logró una fiabilidad de α= .921; con 53

ítems, lo que demuestra una excelente consistencia interna (Hernández Sampieri

et al., 2006). El estadístico Kappa de Cohen (tabla 6) probó que existe una

gran correlación entre las respuestas de los dos observadores, puesto que en la aplicación del instrumento al análisis de

cada red, k ≥ .7 y ρ= .000. De hecho, el grado de acuerdo fue muy

alto en la mayoría. La media total fue de k= .876, lo que se considera un grado

de acuerdo casi perfecto (Abraira, 2000). Este hecho

prueba no solo la reproductibilidad del instrumento (Abraira,

2000), aplicable al análisis de redes sociales de lectura en cualquier idioma,

sino asimismo confirma la pertinencia de la rúbrica diseñada, que ha

proporcionado a los observadores una guía sistemática con criterios fácilmente

identificables y objetivables. Con todo, conviene mencionar que, pese a estos

satisfactorios resultados, las investigadoras decidieron eliminar el ítem 6.3,

porque presentaba puntuaciones muy heterogéneas, con valores tan antagónicos

como el 1 y el 4 en el análisis de la misma red social. La herramienta

definitiva se encuentra en anexo 1.

Tabla 6

Grado de acuerdo de los observadores en el análisis de cada red

|

Redes sociales |

Kappa de Cohen |

|

1 |

.918 |

|

2 |

.866 |

|

3 |

.872 |

|

4 |

.871 |

|

5 |

.857 |

|

6 |

.823 |

|

7 |

.817 |

|

8 |

.917 |

|

9 |

.897 |

|

10 |

.946 |

A

través de este estudio, se ha diseñado y validado la primera batería de indicadores

destinada a evaluar la capacidad de las redes sociales de lectura para

desarrollar el aprendizaje informal y la educación literaria, como reclama la

investigación (Lluch, 2014). Evaluar con precisión y analizar las redes

sociales es fundamental para enfrentar los retos que plantea la sociedad

actual, marcada por la horizontalidad de los saberes y la apropiación social

del conocimiento (Domínguez, 2016). En este contexto, resulta imperativo

identificar los factores con los que abordar la educación literaria para

construir una ciudadanía crítica de lectores que posean las estrategias

necesarias para manejarse.

Se

ha facilitado a los docentes una herramienta que les permita evaluar la

pertinencia del uso de estas plataformas en las aulas según sus objetivos

didácticos. Además, la multidimensionalidad del instrumento les permitirá

cotejar cuáles de sus servicios pueden serles útiles y, por otro lado, saber

qué debe aportar el mediador para contrarrestar aquellas dimensiones en las que

cada red obtiene bajas puntuaciones. Con ello, se pretende acortar la brecha

surgida entre la institución educativa y los contextos informales (De Amo,

2019) mediante la introducción en las aulas de las lecturas vernáculas y la

formalización de los aprendizajes informales (García-Roca, 2021).

Corresponde

destacar, asimismo, la fundamentación de las dimensiones, elaboradas a partir

de una exhaustiva revisión bibliográfica, y el rigor de los métodos de

validación. En este sentido, se ha recurrido a la prueba de juicios expertos

para validar su contenido, como resuelve la literatura académica (Escóbar-Pérez y Cuervo-Martínez, 2008), y tal y como se

había llevado a cabo en la validación de otras herramientas diseñadas también

con fines didácticos. En este proceso, participaron dos jueces más que en otros

estudios (Moral Pérez et al., 2018; Caerio Rodríguez

et al., 2020; Pinilla Morales & Badilla Quintana, 2021) y se aplicó sobre

sus respuestas el cálculo de la media y la desviación típica, como en Gallardo-Montes et al. (2021), y el Coeficiente de Kendall,

como en Caerio Rodríguez et al. (2020). Como

resultado, se reformularon 10 indicadores y se suprimió 1. Más adelante, se

llevó a cabo una muestra piloto sobre 10 aplicaciones escogidas al azar.

Siguiendo el modelo de Pinilla Morales & Badilla Quintana (2021), se

calculó el alfa de Cronbach para medir la consistencia interna de la batería,

arrojando un resultado de .871, superior al valor de .783 que había obtenido

dicho estudio. Asimismo, tomando como referencia la investigación de Moral

Pérez et al. (2018), se utilizó el estadístico Kappa de Cohen para calibrar el

grado de acuerdo entre los observadores con una puntuación de, k=.876, similar

a la de esa investigación, donde k= .897. Pese a estos satisfactorios

resultados, las investigadoras decidieron eliminar el ítem 6.3, porque

presentaba puntuaciones muy heterogéneas

Finalmente,

RESOLEC está compuesto por 52 indicadores agrupados en dos escalas con 3 y 4

dimensiones respectivamente y evaluados a través de una escala Likert de 4

parámetros. A diferencia de la herramienta diseñada por Asadi

et al. (2017), centrada en evaluar las funcionalidades y servicios técnicos que

ofertan estas redes, RESOLEC aborda aspectos educativos como la labor de

mediación de estas redes, su capacidad para integrar a los usuarios en procesos

de creación colectiva, para guiar la interpretación de las obras o para

familiarizar al lector con el dominio del metalenguaje literario y la

intertextualidad.

Evaluating the use of book social networks in

literature instruction in formal and informal contexts. Designing and

validating the RESOLEC tool

1.

Introduction

Social media have become the preferred socialisation

space for young people to engage in personal contact with their peers (Calvo

& San Fabián, 2018). Social media websites record the most visits and are

mostly used by adolescents (Capilla & Cubo, 2017). Given their success,

several studies have emphasised their educational potential (Ferreira-Borges

& França-Teles, 2019; Figueras-Maz et al., 2021) as new resources to

attract young students’ attention. However, as Valencia et al. (2020) point out

in their systematic review, there is some homogeneity in the methods chosen to

explore the use of social media in educational contexts as most academics use

questionnaires.

The platforms that this new media ecology (Scolari,

2017) offers include book social networks, where users register voluntarily

(Lluch, 2014) to share their love of literature (De Amo, 2019). Reading sparks

social conversation (Borrás, 2010) in all the activities promoted by networks

such as Goodreads or Lecturalia, which is why the features of classic book

clubs have been updated by Web 2.0 functionalities (Asadi et al., 2017). This

means readers can publicise and rate the books they have already finished,

reflect on their reading experiences, create discussion groups, set up their

personal reading profile and establish future reading goals (Sánchez-García et

al., 2021). These websites create an environment of collaboration and

reciprocity (Moody, 2019) that defines all stages: from selecting a text to the

final rating (García-Roca, 2020). Consequently, the interface becomes a place

of belonging (Lluch, 2014) where users seek to integrate into the community and

be accepted as members (Ramos & Oliva, 2018).

Given the attention these paratexts receive from

readers and their influence as cultural mediation models (Sánchez-García et

al., 2021), the academic literature recommends selecting indicators to rate

their quality and effectiveness (Lluch et al., 2015), although this research

practice has been quite unusual to date. While some studies have explored the

advantages of these networks in encouraging reading or learning (Lluch, 2014;

García-Roca, 2020; 2021), none has designed a tool to rate their performance in

terms of literature instruction or informal learning. In fact, the methods

selected in these works include surveys (García-Roca, 2020; Thelwall &

Kousha, 2017), content analysis (Montesi, 2015; Driscoll & Rehberg, 2018;

Moody, 2019) or bibliometric studies (Piryani et al., 2018; Thelwall, 2019;

Kadiresan et al., 2020).

However, two studies are worth highlighting: in the

first, by Moradi & Safavi (2013), the authors created a checklist of 49

indicators grouped into eight dimensions (profile, privacy, networking

capabilities, membership search, book search, technical information and book

status); in the second, by Asadi et al. (2017), there is a rubric of 35

indicators grouped into nine dimensions (security and privacy issues,

demographic properties, profiles, interaction, friend search, technical

support, book search, groups and book status). Unlike the instrument proposed

below, which was created for educational purposes, the architectures of the

rubrics in both articles are based on webometrics to explore the design and

structure of this type of network from a technical and communicative

standpoint.

This study therefore aims to design and validate an

instrument for teachers to assess the potential of book social networks for

developing informal learning and literature instruction. Thus, new tools could

be offered to build bridges between formal, informal and non-formal learning,

as called for by research (Davies, 2017). The set of indicators is based on the

activity theory and the paradigm of literature instruction. These constructs

were selected to examine what is being learned, in both educational and

literary terms, in these increasingly popular services.

1. 1. The activity theory applied to social media

The activity theory (AT) makes it possible to examine

individual and collective exercise mediated by an artefact in a given context

(Kuutti, 1996), since it assumes learning is the outcome of individuals’ social

and cultural exchange in collective practices. Devised by Leont’ev (1974) and

Engeström (1987), it has been applied as theoretical scaffolding in several

learning environments related to the use of digital technologies, both in

formal (Lim & Hang, 2003; Collis & Magaryan, 2004) and informal

learning contexts (Park et al., 2011; Heo & Lee, 2013; Jiménez Cortés,

2019). In these studies, ICTs encourage the creation of learning networks that

reward members with knowledge acquisition, reflection on their own experience

or identity development.

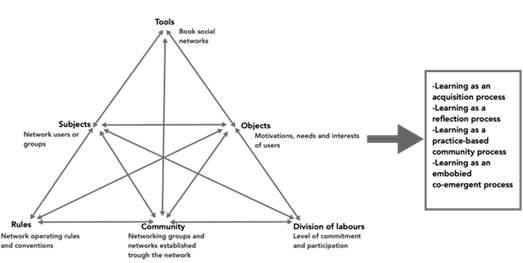

To achieve these objectives, the activity is organised

as a complex triangular system of iterations between six components. The

subjects in our case (Fig. 1) are the individuals or subgroups participating in

book social networks, which are the mediating learning tools shaping the

interaction space. The objects comprise users’ motivations, needs and

interests—in this case linked to the reading experience. User participation

depends on labour organisation and adoption of a variety of roles and

commitments acquired with the community, which, in turn, is arranged through

groups and an extensive network of contacts and whose stability is regulated by

the conventions and rules those same networks impose.

Figure 1

Triangular structure

of the activity theory applied to book social networks based on Engeström

(1987).

Based on Fenwick and Tennant (2004), Park et al.

(2011) specify the output produced by the synchronous operation of this system:

·

Learning as an acquisition process: this occurs when

individuals gain new skills and expertise by reading and receiving, without

adopting a proactive stance whereby they help create new content.

·

Learning as a reflection process: this is achieved

when users engage in the collective creation of meaning by transforming

existing knowledge or making new knowledge while reflecting on content (what

was learned) or process (how).

·

Learning as a practice-based community process: this

is possible when the subjects, as full participants, act at all collective

levels. Knowledge is created through communication with others based on

cooperation, exchange and negotiation links, which can lead to a refined

individual or group identity.

·

Learning as an embodied co-emergent process: it takes

place when learning systems and participants adapt, organise and transform

simultaneously.

1.2. Literature instruction

The task of literature instruction is currently to

educate students to become competent readers (Tabernero, 2005). Colomer (1996)

identifies the two main aims of literature instruction: developing

interpretation skills and forming reading habits that encourage a pleasurable

and personally committed relationship with reading. The aim is to develop

‘engaged readers’, in other words, intrinsically motivated readers who use

their cognitive tools to decode, interpret and apply what they read in

personal, social and intellectual contexts (Gambrell, 2011).

Achieving it, insofar as improving interpretation

skills is concerned, requires acquiring knowledge to be able to read and

interpret texts (Mendoza, 1998), some proficiency in disciplinary metalanguage

(Langer, 1995) and intertextuality, and knowledge of the context of the books (Colomer,

2005). The mediator’s role is to advocate joint reading, giving readers freedom

while guiding them in the interpretation process (Sanjuán, 2013). The academic

literature proposes several practices for mediation aimed at consolidating

reading habits, such as play (Chou et al., 2016), contact with authors,

publishers and libraries (Patte, 2011) and linking reading with writing

(Alvarado, 2013). Langer (1995) adds the importance of recipients having the

autonomy to construct their self-image as readers.

The gradual updating of literature instruction has

brought into focus literary discussion, which is based on peer-to-peer conversation

to share thoughts and experiences and ‘co-generate’ the meaning of the text

(López Valero et al., 2021). Nevertheless, although readers having autonomy is

advisable to stimulate discussion, they also need the contribution of a

mediator (Munita, 2021) who asks questions that move from the generic to the

specific and adapts the discussion format to the specificity of the texts

(Chambers, 2007).

The importance of the corpus in literature instruction

is also relevant. It must be extensive and varied, although the selection

should follow specific criteria based on quality, variety of topics and

readers’ interests (Colomer, 2005). Teachers who base activities on students’

individual choices help to reinforce their autonomy and feeling of control (Jang

et al., 2010). Although the corpus structure must factor in readers’ likes, the

mediator must also include works that benefit the target audience (Margallo,

2012). As Gambrell (2011) summarises, one of the features of effective reading

instruction is offering works that help students to progress rather than

overwhelm them.

2. Method

2.1. Objectives

This study aims to design and validate

an instrument for compulsory and post-compulsory secondary education teachers

to assess the potential of book social networks for encouraging informal

learning and literature instruction so they can incorporate them into their

teaching practice (Watlington, 2011). As part of this broad purpose, the

specific objectives of the research are as follows:

1.

Identifying and establishing

study constructs in several dimensions and extrapolating them to the instrument

using several indicators;

2.

Validating the content of the

tool using a test involving expert judges;

3.

Validating the reliability of

the instrument through a pilot test consisting in analysing a random sample of

book social networks using it.

2.2. Procedure. Participants and data analysis

techniques

Phase 1: instrument

construction

A review of the literature was

conducted before designing the tool. This process led to a first version of

RESOLEC, an instrument comprising two scales: the first consisting of three

dimensions and the second of four. This evaluation tool included 54 indicators,

which were to be rated using a 1-to-4 Likert scale, where 1 = Never, 2 =

Seldom, 3 = Usually, 4 = Always. These scales were based on two constructs: the

activity theory applied to social networks (first scale) and literature

instruction (second scale).

To analyse the potential of

these networks for informal learning, this research was based on the dimensions

validated by Fenwick & Tennant (2004), Park et al. (2011) and Jiménez

Cortés (2019): 1) learning as an acquisition process; 2) learning as a

reflection process; 3) learning as a practice-based community process; and 4)

learning as an embodied co-emergent process. However, only the first three have

been adapted for the study in question as they are relevant and match the

objectives set by the researchers. Since these dimensions had only been adopted

to design questionnaires for social media users, they had to be rephrased.

Consequently, the items aim to measure the ability of networks to promote the

three learning types. Already validated indicators have been rephrased as far

as possible. Specifically, items 1, 7, 12, 13 and 15 have been adapted from the

research by Jiménez Cortés (2019).

The following were selected to

configure the dimensions in the literature instruction block:

·

1) Developing interpretation

skills and 2) forming reading habits as a pleasurable and personally committed

relationship with books. Both dimensions therefore correspond to the two

specific objectives associated with literature instruction according to the

academic literature (Colomer, 1996).

·

3) Literary discussion. This

dimension is one of the leading ‘disciplinary genres’ (Dias-Chiaruttini, 2014)

of literature instruction. It plays a prominent role in these networks as they

provide spaces for dialogue and debate.

·

4) The corpus, as well as the

criteria for selecting it (Colomer, 2005). This dimension is a central aspect

in book social networks, given their extensive book databases.

Phase 2. Refining the initial

tool

To validate the content and

reliability of the instrument (Escóbar-Pérez & Cuervo-Martínez, 2008), a

test involving expert judges was conducted to analyse the extent to which the

items were representative of the study constructs (Beck & Gable, 2001). The

choice of participants was deliberate and based on inclusion criteria

established by the researchers (Rodríguez et al., 1996). This resulted in

selecting experts that were familiar with building and adapting tools and

judges specialised in the construct of interest or with experience in the

discipline they are part of rather than in psychometrics,(Davis, 1992). Thus,

eight experts from the fields of communication, education and literature

didactics cooperated with the research (Table 1); all of them had a personal

account on a social media site.

Professional profile of the

expert judges

|

Qualification |

Job |

Experience in measurement

methods |

|

Audiovisual Communication |

Senior Lecturer in the Area

of Journalism |

Yes |

|

Journalism |

Marketing and Communication

Manager |

No |

|

Journalism |

Digital Marketing and

Ecommerce Manager |

No |

|

Spanish Language and

Literature |

Lecturer in the Area of

Didactics of Language and Literature |

Yes |

|

Spanish Language and

Literature |

Senior Lecturer in the Area

of Didactics of Language and Literature |

Yes |

|

Spanish Language and

Literature |

Lecturer in the Area of

Didactics of Language and Literature |

Yes |

|

Pre-school Education |

Lecturer in Education |

Yes |

|

Primary Education |

Lecturer in Education |

Yes |

The template completed by the experts was based on

Delgado-Rico et al. (2012) and included: the test instructions; the definition of

both constructs and their characteristics; a table for compiling the judges’

personal and professional data; the set of indicators; and a checklist of five

categories that the experts would use to quantitatively rate the ‘clarity’,

‘coherence’ and ‘relevance’ of the items and the ‘adequacy’ and ‘suitability’

of the dimensions using a Likert scale, where 1 = very inadequate, 2 =

inadequate, 3 = adequate, 4 = very adequate. Several spaces were also provided

for the experts to give qualitative ratings.

The data were analysed following several procedures

and using Microsoft Excel and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. The

first part of the analysis consisted of calculating the mean and standard

deviation of the items in the ‘clarity’, ‘coherence’ and ‘relevance’ categories

and of the dimensions in terms of their ‘adequacy’ and ‘suitability’. Items

that did not reach a mean score ≥ 3 for ‘coherence’ and ‘relevance’ were

eliminated, while indicators with a mean score below the ‘adequate’ parameter

in the ‘clarity’ category were rephrased. The content validity ratio for

ordinal scales was then applied to measure which items the experts rated as

adequate (McGartland et al., 2003). The content validity index (CVI) for each

item was calculated by dividing the number of judges who had rated it with 3 or

4 by the total number of judges. Indicators reaching an index >.80 in all

categories were considered valid for interpretation purposes. Finally, the

Kendall coefficient was measured to gauge inter-observer reliability (Bao et

al., 2009), with a range from 0 to 1, where 1 represents total agreement and 0

represents total disagreement (Dorantes-Nova et al., 2016).

Phase 3: pilot test

Before conducting the pilot test, an analytical rubric

was designed to guide the observers’ evaluation using objective criteria based

on reading the academic literature and exploring the websites. As the complete

rubric cannot be attached for space reasons, the descriptors for rating one of

the items are shown below by way of example (Table 2).

Small example of the

analytical rubric

|

Item |

1 =

Never |

2 =

Seldom |

3 =

Usually |

4 =

Always |

|

Allows

users to rate other members’ creations |

Never |

Allows

users to qualitatively rate other members’ creations |

Allows

users to qualitatively rate other members’ creations and through like |

Allows

users to qualitatively rate other members’ creations and through ‘like’ and

‘dislike’ |

A sample of ten applications was then randomly

selected from a universe of 24. The selection depended on the following

requirements: free of charge throughout the Web, online accessibility and,

lastly, the specific objective of their set-up (online reading). An attempt was

also made to include websites with interfaces offered in different languages in

the collection of networks of the pilot study. Consequently, four English, two

French, two Spanish and two German networks were analysed.

Two previously trained observers rated the

applications using the set of items. According to Cohen’s kappa statistic

(1960), chosen to compare the concordance of their ratings, moderate agreement

began from .41. Cronbach’s alpha was applied to the complete scale to ensure the

internal consistency of the indicator system, considering that the closer the

coefficient is to 1, the more consistent the items are with each other

(Hernández Sampieri et al., 2006).

3. Analysis and results

3.1. Refining the initial

instrument

Once

the judges had completed the evaluation form and mean, standard deviation and

CVI for each item had been calculated (Table 3), several modifications were

made (shown in brackets) based on the experts’ qualitative and quantitative ratings.

Table 3

Mean, standard deviation and

CVI of items with M < 3 in the ‘clarity’, ‘coherence’ or ‘relevance’

categories

|

Item |

Clarity |

Coherence |

Relevance |

|||||||

|

M |

ST |

CVI |

M |

ST |

CVI |

M |

ST |

CVI |

|

|

|

Scale 1: informal learning |

||||||||||

|

1.2. Introduces

own content through entries made by the workers of the social network |

2 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

1.3.

Censures unacceptable or incorrect content |

2.5 |

.535 |

.625 |

3.38 |

.518 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

1.4. Contributes

to developing user experience in several areas |

2.63 |

.518 |

.75 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2.5.

Provides spaces for discussion |

2.63 |

.518 |

.75 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

2.6 Includes

ways for users to report content they consider abusive or offensive |

2.13 |

.641 |

.25 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

|

|

3.8.

Allows the social promotion of users within a hierarchy imposed by the

network |

2.5 |

.535 |

.625 |

3.5 |

.535 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Scale 2: literature

instruction |

||||||||||

|

4.3.

Uses concepts of the literary system |

2.88 |

.354 |

.75 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

|

|

4.6

Tagging processes respond to literary criteria |

2.88 |

.354 |

.875 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

3.25 |

.463 |

1 |

|

|

7.2. Imposes

inclusion criteria for book selection |

2.88 |

.354 |

.75 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

7.4

Guides readers in the choice of texts by proposing books that differ completely

from their interests to broaden their literary horizons |

2.13 |

.354 |

.25 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

0 |

1 |

|

Items

1.2 (‘incorporates own publications’), 1.3 (‘corrects content produced by users

if it is incorrect’) and 4.6 (‘reviews the tags assigned to the book

description if they are incorrect’) were rephrased due to their low score (mean

< 3 and CVI of < .81) in the ‘clarity’ category; the wording of

indicators 1.4 (‘allows users to improve their experience in different areas’),

2.6 (‘includes ways for users to report content they consider abusive’), 7.2

(‘imposes inclusion criteria for book selection’) and 7.4 (‘guides readers in

the choice of texts by proposing books that differ completely from their

interests’) were simplified; items 2.5 (‘enables spaces for discussion’), 3.8

(‘allows the social advancement of users within a hierarchy imposed by the

network’) and 4.3 (‘appropriately uses concepts of the literary system’) were

defined more precisely; and 5.3 was eliminated because of ‘coherence’ and

‘relevance’ scores of < 3 and a CVI of <.81. The subject of the statement

was also added to all the items on the recommendation of one of the experts.

Even with the above items’ low indices, the content of the instrument is

adequate since CVI = .90 for ‘clarity’ and CVI = .98 for ‘coherence’ and

‘relevance’.

As

Table 4 shows, all the dimensions were considered suitable, and the items

comprising them were considered adequate for measuring each of them.

Table 4

Mean and standard deviation by

dimensions

|

Dimension |

Adequacy |

Suitability |

||

|

M |

ST |

M |

ST |

|

|

1. Learning as an acquisition process |

3.88 |

.354 |

4 |

0 |

|

2. Learning as a reflection process |

3.38 |

.518 |

3.38 |

.518 |

|

3. Learning as a practice-based community process |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

4. Interpretation skills |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

5. Forming reading habits as a pleasurable and personally committed

relationship with books |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

|

6. Literary discussion |

3.38 |

.518 |

4 |

0 |

|

7. Corpus |

4 |

0 |

4 |

0 |

Concerning the judges’ level of agreement with each other (Table 5),

there is statistical significance for ‘clarity’, ‘coherence’ and ‘relevance’ in

all the dimensions; agreement is high in dimensions 1 and 7 for ‘clarity’ and

low in dimension 6 for ‘coherence’. In general, the judges’ level of agreement

with each other is moderate-high. The experts’ level of agreement with each

other in each category of the instrument also exhibits statistical significance

(ρ < .05), with .744 for ‘clarity’, .672 for ‘coherence’, .682 for

‘relevance’, .625 for ‘suitability’ and .567 for ‘adequacy’.

Kendall coefficients and

statistical significance of the dimensions in the measurement tool

|

Dimensions |

Clarity |

Coherence |

Relevance |

|||

|

Kendall Coefficient |

|

Kendall Coefficient |

|

Kendall Coefficient |

|

|

|

D1 |

.933 |

.000 |

.625 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

|

D2 |

.883 |

.000 |

.845 |

.000 |

.611 |

.000 |

|

D3 |

.733 |

.000 |

.614 |

.000 |

.506 |

.000 |

|

D4 |

.764 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

|

D5 |

.717 |

.000 |

.743 |

.000 |

.824 |

.000 |

|

D6 |

.759 |

.000 |

.500 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

|

D7 |

.852 |

.000 |

.750 |

.000 |

.679 |

.000 |

3.2. Pilot test

RESOLEC achieved a reliability

of α= .921 with 53 items, thus demonstrating excellent internal consistency

(Hernández Sampieri et al., 2006). Cohen’s kappa statistic (Table 6) proved

there is a high correlation between both observers’ responses since when the

tool was applied to analyse each network, k ≥ .7 and ρ= .= .000. In

fact, the level of agreement was very high in most of them. The overall mean

was k = .876, which is considered a near perfect level of agreement (Abraira,

2000). This not only proves the reproducibility of the instrument (Abraira,

2000)—applicable to the analysis of book social networks in any language—but

also confirms the relevance of the designed rubric, which has provided the

observers with a systematic guide with easily identifiable and objectifiable

criteria. Despite these satisfactory results, the researchers decided to eliminate

item 6.3 because of its highly diverse scores, with values as antagonistic as 1

and 4 in the analysis of the same social network. The definitive tool can be

found in annex 1.

Table 6

Observers’ level of agreement in analysing each network

|

Social Networks |

Cohen’s Kappa |

|

1 |

.918 |

|

2 |

.866 |

|

3 |

.872 |

|

4 |

.871 |

|

5 |

.857 |

|

6 |

.823 |

|

7 |

.817 |

|

8 |

.917 |

|

9 |

.897 |

|

10 |

.946 |

4. Discussion and conclusions

This study presents the design

and validation of the first set of indicators for evaluating the potential of

book social networks for developing informal learning and literature

instruction, as stated by research (Lluch, 2014). Accurately evaluating and analysing social media is crucial to deal with the

challenges posed by today’s society, which is characterised

by the horizontality and social appropriation of knowledge (Domínguez, 2016).

In this context, identifying factors that can be used in literature instruction

to create a critical mass of readers with the strategies they need to manage by

themselves is vital.

This paper has provided

teachers with a tool that allows them to evaluate the appropriateness of using

these platforms in the classroom depending on their educational objectives. The

multidimensionality of the tool will also enable them to check which services

they may find useful and learn what mediators should contribute to compensate

for dimensions in which the network obtains a low score. As a result, the aim

is to bridge the gap between the educational institution and informal contexts

(De Amo, 2019) by introducing vernacular reading into the classroom and making

informal learning more formal (García-Roca, 2021).

The dimensions are also substantiated

by an exhaustive literature review and thorough validation methods. A test

involving expert judges was used to validate the content, as established by the

academic literature (Escóbar-Pérez and

Cuervo-Martínez, 2008), and as other tools also designed for educational

purposes were validated. This process included two judges more than other

studies (Moral Pérez et al., 2018; Caerio Rodríguez

et al., 2020; Pinilla Morales & Badilla Quintana, 2021) and their responses

were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation, as in Gallardo-Montes

et al. (2021), and the Kendall coefficient, as in Caerio

Rodríguez et al. (2020). As a result, ten indicators were rephrased

and one was eliminated. A pilot sample was then conducted on ten randomly

selected applications. Following the model of Pinilla Morales & Badilla

Quintana (2021), Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the internal

consistency of the set of indicators, giving a result of .871, which is higher

than the value of .783 these authors obtained in their study. Taking the

research by Moral Pérez et al. (2018) as a reference, Cohen’s kappa statistic

was used to calibrate the observers’ level of agreement with each other with a

score of k = .876, which is similar to the score

attained in their research, where k = .897. Despite these satisfactory results,

the researchers decided to eliminate item 6.3 because of its highly diverse

scores.

Finally, RESOLEC comprises 52

indicators grouped into two scales with three and four dimensions,

respectively. It is rated using a four-parameter Likert scale. Unlike the tool

designed by Asadi et al. (2017), which focuses on evaluating the

functionalities and technical services of these networks, RESOLEC addresses

educational aspects, such as their mediation efforts and ability to integrate

users in collective creation processes, to help readers interpret texts or

become proficient in literary metalanguage and intertextuality.

References

Abraira,

V. (2000). El índice Kappa. Semergen, 27,

247-249.

Asadi, S., Nourmohammadi, H.,

& Ardali, M. O. (2017). Evaluation and ranking of book social network

websites. International Journal of Information Science and Management, 15(1),

95–108.

Bao, S., Howard,

N., Spielholz, P., Silverstein, B. & Polissar, N.

(2009) Inter-rater reliability of posture observations Human Factors. The Journal of the Human Factors and

Ergonomics Society, 51(3), 292-309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720809340273

Beck, C.T.

& Gable, R.K. (2001). Ensuring content validity: An illustration of the

process. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 9, 201-215.

Borrás,

L. (2010). Nuevos lectores. Nuevos modos de lectura en la era digital. En S.

Montesa (Ed.). Literatura e internet. Nuevos textos, nuevos lectores,

(pp. 41-66). AEDILE

Caerio Rodríguez, M., Ordoñez Fernández, F. F., Callejón

Chinchilla, M. D., & Castro León, E. (2020). Diseño de un instrumento de

evaluación de aplicaciones digitales (Apps) que permiten desarrollar la

competencia artística. Pixel-Bit, Revista de

Medios y Educación, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.74071

Calvo,

S., & San Fabián, J.L. (2018). Selfies, jóvenes y

sexualidad en Instagram: representaciones del yo en formato imagen. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 52,

167-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i52.12

Capilla,

E. & Cubo, S. (2017). Phubbing. Conectados a la

red y desconectados de la realidad. Un análisis en relación

al bienestar psicológico. Pixel-Bit: Revista de

medios y educación,

50, 173-185. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2017.i50.12

Chambers,

A. (2007). El ambiente de lectura. Fondo

de Cultura Económica.

Cohen,

J. (1960). A

coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol

Meas, 20, 37-46.

Colomer,

T. (1996). La didáctica de la literatura: temas y líneas de investigación e

innovación. En Lomas, C. (Coord.) La

educación lingüística y literaria en la enseñanza secundaria. Cuadernos de

formación del profesorado. Horsori.

Colomer, T. (2005). Andar entre libros.

Lectura literaria en la escuela. Fondo de Cultura Económica

Davies, R.

(2017). Collaborative Production and the Transformation of Publishing: The Case

of Wattpad. In J. Graham, & A. Gandini (Eds.), Collaborative Pro- duction in the Creative Industries (pp. 51-68).

University of Westminster Press.

Davis L.L.

(1992). Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Applied 1'iursing Research, 5, 194-197.

De

Amo, J. M. (2019). La mutación cultural: estudios sobre lectura digital. En J.

M. de Amo (Coord.), Nuevos modos de

lectura en la era digital, (pp. 15-40). Editorial Síntesis.

Delgado-Rico,

E., Carretero-Dios, H. & W. Ruch (2012). Content validity evidences in

test development: An applied perspective. International Journal of Clinical

and Health Psychology, 12, 3, 449-459.

Dias-Chiaruttini, A. (2014). Le

débat interprétatif dans l’enseignement du français. Peter

Lang.

Domínguez,

E. (2016). Apropiación del conocimiento. Foro

del Oriente, Diálogo de saberes y oportunidades de región. Universidad de

Antioquia.

Dorantes-Nova,

J. A., Hernández-Mosqueda, J. S. & Tobón-Tobón, S. (2016). Juicio de

expertos para la validación de un instrumento de medición del síndrome de

Burnout en la docencia. RA Ximhai, 12(6), 327-346. https://doi.org/10.35197/rx.12.01.e3.2016.22.jd

Driscoll,

B.& Rehberg, D. (2018). Faraway, So Close: Seeing the Intimacy in Goodreads

Reviews. Qualitative

Inquiry, 25(3),

248-259. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418801375

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning

by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsultit.

Escóbar-Pérez, J. & Cuervo-Martínez, Á.

(2008). Validez de contenido y juicio de expertos: una aproximación a su

utilización. Avances en Medición, 6, 27-36.

Fenwick, T.,

& Tennant, M. (2004). Understanding adult learners. In G. Foley (Ed.), Dimensions of adult learning: Adult

education and training in a global era adult education and training (pp.

55-73). Allen & Unwin.

Ferreira-Borges,

F., & França-Teles, L. (2019). El uso de redes sociales

en la práctica educativa de una asignatura de postgrado: una investigación

sobre el uso de las TRIC. Index.Comunicación, 9(1),

109–125.

Figueras-Maz, M., Grandío-Pérez, M. D,

& Mateus, J. C. (2021). Students’

perceptions on social media teaching tools in higher education settings. Communication & Society,

34(1),15-28.

Gallardo-Montes, C. D. P., Caurcel-Cara,

M. J., & Rodríguez-Fuentes, A. (2021). Diseño de un sistema de indicadores

para la evaluación y selección de aplicaciones para personas con Trastorno del

Espectro Autista. Revista Electrónica Educare, 25(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.15359/ree.25-3.18

Gambrell, L.

(2011). Seven rules of Engagement. The

Reading Teacher, 65(3), 172-178. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRTR.01024

García-Roca,

A. (2020). Lectura virtualmente digital: el reto colectivo de interpretación

textual. Cinta de Moebio,

67, 65-74.

García-Roca,

A. (2021). Nuevos mediadores de la LIJ: Análisis de los booktubers

más importantes de habla hispana. Cuadernos

info, 48, 94-114. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.48.27815

Hernández

Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C. & Baptista Lucio, P. (2006). Metodología de la investigación.

McGraw-Hill.

Jang,

H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E.L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not

autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology,

102(4), 588–600. https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0019682

Kadiresan,

N., Singson, S. & Thiyagarajan, S. (2020). Examining the relationship

between academic book citations and goodreads reader

opinion and rating. Annals of Library and

Information Studies, 67(4), 215-221.

Kuutti, K.

(1996). Activity theory as a potential framework for human–computer interaction

research. In B. Nardi (Ed.), Contextandconsciousness:

Activity theory andhuman–computerinteraction,

(pp. 17–44). MITPress.

Langer, J.

A. (1995). Enviosing literatura:

literacy understanding and literature instruction. Teachers College Press.

Leont'ev, A. N. (1978).

Activity, consciousness, and personality. Prentice-

Hall.

Lluch,

G. (2014). Jóvenes y adolescentes hablan de lectura en la red. Ocnos, 11, 7-20.

Lluch,

G., Tabernero-Sala, R. & Calvo-Valios, V. (2015).

Epitextos virtuales públicos como herramientas para

la difusión del libro. El Profesional de

la Información, 24(6), 797-804. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2015.nov.11.

López

Valero, A., Encabo, E., Jerez Martínez, I. & Hernández Delgado, L. (2021). Literatura infantil y lectura dialógica: la

formación de educadores desde la investigación. Octaedro.

Margallo,

A. (2012). El reto de elaborar un corpus para la formación literaria de

adolescentes reticentes a la lectura. Anuario

de Investigación en Literatura Infantil y Juvenil, 10, 69-85.

McGartland,

D. Berg, M., Tebb, S. S.,

Lee, E. S. & Rauch, S. (2003). Objectifying content validity: Conducting a content

validity study in social work research. Social Work Research, 27(2),

94-104.

Mendoza

Fillola, A. (1998). Conceptos clave en didáctica de la

lengua y la literatura. Barcelona:

SEDLL.

Montesi, M.

(2015). Reading in social networks: analysis possibilities for researchers. Revista Ibero-Americana

de Ciencia de la Información, 8(1), 67-81.

Moody,

S. (2019). Bullies and blackouts:

Examining the participatory culture of online book reviewing. Convergence, 25(5-6), 1063-1076. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517721805

Moradi, K.

& Safavi, Z. (2013). Comparative Study of Iranian Professional Book Reader

network with 3 global book social networks. In The proceedings of 4th Student Conference on Mediacal

Library and Information. Beheshi University of

Medical Sciences.

Moral Pérez,

E., Bellver, C. & Guzmán, A. (2018). CREAPP

K6-12. Digital Education Review, 22,