Computación en la Nube y Software Abierto para la Escuela

Rural Europea

Cloud Computing and Open Source Software for

European Rural Schools

Dra.

Maria José Rodríguez Malmierca. Centro de Supercomputación de Galicia.

Santiago de Compostela. España

Dra.

Maria José Rodríguez Malmierca. Centro de Supercomputación de Galicia.

Santiago de Compostela. España

Dra. María del Carmen Fernandez Morante. Profesora Titular de Universidad.

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España

Dra. María del Carmen Fernandez Morante. Profesora Titular de Universidad.

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España

Dra. Beatriz

Cebreiro López. Profesora Titular de

Universidad. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España

Dra. Beatriz

Cebreiro López. Profesora Titular de

Universidad. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España

Dr. Francisco

Mareque León. Profesor asociado.

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España

Dr. Francisco

Mareque León. Profesor asociado.

Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España

Recibido:

2022/02/09; Revisado 2022/03/23; Aceptado: 2022/04/18; Preprint: 2022/04/29 Publicado: 2022/05/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Fernández-Morante, C., Rodríguez-Malmierca, M.J., Cebreiro-López, B., & Mareque-León, F. (2022). Computación en la Nube y Software

Abierto para la Escuela Rural Europea [Cloud Computing and Open Source Software for European Rural Schools]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 64, 105-137. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.93937

RESUMEN

La tecnología de la computación

en la nube ofrece grandes posibilidades en contextos con dificultades de

infraestructura y pueden proporcionar un puente para ayudar a superar la brecha

existente en las escuelas rurales europeas por su falta de recursos,

aislamiento, sus limitaciones en las infraestructuras y de soporte tecnológico.

El propósito de este estudio fue diseñar, implementar y evaluar un entorno para

la enseñanza flexible y la colaboración en centros educativos rurales de Europa

basado en la tecnología de computación en la nube y se llevó a cabo en el marco

de un proyecto de investigación europeo (RuralSchoolCloud).

Para ello se realizó una investigación basada en diseño (IBD) en 14 escuelas

rurales de cinco países europeos (Dinamarca, España, Gran Bretaña, Italia, Grecia).

La muestra objeto de estudio queda conformada por un total de 560 estudiantes y

72 docentes de educación Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria obligatoria que

contestaron el "Cuestionario de análisis del entorno educativo RSC de

computación en la nube". En términos generales, los resultados muestran

que el entorno educativo RSC demostró ser una herramienta potente para

proporcionar un recurso educativo técnico funcional y utilizable para las

escuelas rurales de la UE, permitiendo flexibilidad temporal y espacial en las

interacciones de profesores y estudiantes, y proporcionando una herramienta

adaptada a las diferentes características, necesidades e intereses de las

escuelas rurales.

ABSTRACT

Cloud computing technology

offers great possibilities in contexts with infrastructural difficulties and

can provide a bridge to help overcome the existing gap in European rural

schools due to their lack of resources, isolation, infrastructural limitations

and technological support. The purpose of this study was to design, implement

and evaluate an environment for flexible teaching and collaboration in rural

schools in Europe based on cloud computing technology and was carried out in

the framework of a European research project (RuralSchoolCloud). For this

purpose, a design-based research (DBR) was conducted in 14 rural schools in

five European countries (Denmark, Spain, UK, Italy, Greece). The study sample

consisted of a total of 560 students and 72 teachers of kindergarten, primary

and compulsory secondary education who answered the "Questionnaire for the

analysis of the cloud computing RSC educational environment". Overall, the

results show that the RSC educational environment proved to be a powerful tool

to provide a functional and usable technical educational resource for EU rural

schools, allowing temporal and spatial flexibility in teacher and student

interactions, and providing a tool adapted to the different characteristics,

needs and interests of rural schools.

PALABRAS CLAVES · KEYWORDS

Innovación educativa; Tecnología Educativa; Sistemas

escolares rurales; Métodos de aprendizaje; Competencia digital.

Educational innovation; educational technology; Rural

school system; Learning methods; Digital competence.

1. Introducción

Aunque

hay múltiples definiciones sobre la computación en la nube (cloud

computing) una de las más aceptadas en el ámbito

tecnológico es la que propone la NIST:

“La

computación en la nube es un modelo para permitir el acceso, ubicuo,

conveniente, y bajo demanda, a una serie de recursos de computación

configurables (p.ej. redes, servidores, almacenamiento, aplicaciones y

servicios) que pueden proporcionarse y ponerse en marcha con un mínimo esfuerzo

de gestión o de intervención del proveedor de servicio”. (Mell

& Grance, 2011)

En

esta definición se insiste en la idea de la sencillez (o mínima intervención) de otros agentes que no sean el usuario

final para disponer de estos recursos de computación, retomando la metáfora de la disposición de recursos de computación

de forma sencilla y transparente como sucede con la provisión de la red

eléctrica. (Carr, 2009)

Aunque

a veces parece difícil distinguir la frontera entre lo que se entiende como

oportunidades de la computación en la nube para la escuela y las posibilidades

de Internet o de la escuela conectada (Magro, 2015) para este fin, en la

literatura científica aparecen algunas voces e iniciativas como Katz (2008) o Qasem et al.( 2019) que resaltan el potencial del

ecosistema de computación en la nube como una oportunidad única para poder

flexibilizar el acceso masivo a recursos educativos y su reutilización desde

grandes repositorios heterogéneos o federaciones de nubes con fines educativos,

que proporcionen una base de conocimiento universalmente accesible.

1.1. La computación en la nube en la escuela

La

rápida evolución tecnológica y sus servicios requieren un esfuerzo constante

para dotar a la escuela de mecanismos para proporcionarle software y hardware

que se ajuste a sus necesidades (Sharma, et al., 2020). Investigadores de la Hellenic American University (Kalagiakos & Karampelas,

2011) en su artículo resaltaban la necesidad de que la comunidad educativa

mundial pueda beneficiarse del movimiento de los contenidos educativos

abiertos, y que gracias a la computación en la nube estos puedan ser integrados

con facilidad por educadores desde cualquier parte del mundo. Así, se critica

que repositorios de objetos de aprendizaje abiertos, como el promovido por OpenCourseWare Consortium, no

sigan unos estándares que faciliten su reutilización o la integración de sus

valiosos recursos de aprendizaje en una infraestructura en la nube, a través

del desarrollo de un Sistema Operativo Educativo en la Nube para facilitar la

gestión de los mismos. Así, proponen una iniciativa

denominada “Federación de Computación en la Nube Educativa Abierta” (OCCEF) que

facilite la reutilización sencilla de los materiales educativos por parte de

cualquier institución entre diferentes sistemas en la nube, una vez que los

problemas identificados sobre la portabilidad e interoperabilidad de los

sistemas sean resueltos. Estas dificultades no residen fundamentalmente en los

aspectos técnicos, sino en las voluntades de los diferentes actores

institucionales y políticos.

Los

investigadores Sasikala y Prema

(2010) proponen como escenario futuro el diseño y despliegue de una Computación

en la Nube Masiva y Centralizada para la educación (MCCC). Con este modelo, el

profesorado y alumnado tendría acceso a los recursos en cualquier momento y

desde cualquier punto, ofreciendo aplicaciones y servicios para toda la

comunidad educativa con su propia selección de aplicaciones y servicios. El

modelo de almacenamiento centralizado supone, entre otras ventajas, que la

pérdida de elementos individuales, por ejemplo, la de un portátil que almacena

las notas, no sea un incidente grave, y la monitorización del uso de los

recursos resulte más sencilla para la institución (lo que por otro lado puede

suponer un punto muy delicado por lo que conlleva de pérdida de privacidad).

El

concepto de “la nube” en el centro de esta nueva realidad de nuestras vidas, y

su papel en el ámbito escolar, lleva a

los investigadores Koutsopoulos y Kotsanis (2014) a presentar una visión en la que los

procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje serán centrados en el “alumnado-en-la-nube” (cloud student-centered), en un

marco de integración, no solo tecnológico, sino organizativo, donde todos los

agentes presentes en la educación (estudiantes, profesorado, administración,

familia, comunidad) asumen una función más integrada y presente. Esta

tecnología proporciona, bajo esa visión, un paso más allá del enfoque

constructivista del aprendizaje, donde la tecnología es más que un conjunto de

herramientas y las y los estudiantes participan activamente en el proceso

educativo de manera que les ayude a construir su propio aprendizaje (Jonassen et al., 1998).

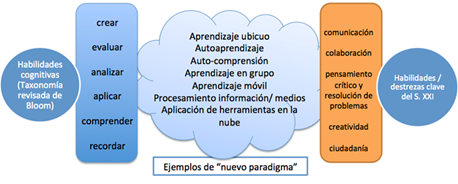

En

este nuevo paradigma del aprendizaje de la mano de la computación en la nube, Koutsopoulos y Kotsanis (2014)

insisten en la necesidad de abordar las ocho competencias clave del Marco

Europeo de Competencias del Aprendizaje a lo Largo de la Vida (Comisión

Europea, 2019), definidas como la combinación de conocimiento, destrezas y

actitudes que como individuos necesitamos para el desarrollo personal, la ciudadanía

activa, inclusión social y empleo. Por otro lado, responde a la necesidad de

los y las estudiantes de adquirir las habilidades, actitudes y cualidades clave

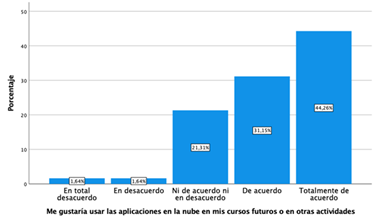

del siglo XXI, tal como se describe en la Figura 1.

Ejemplos de nuevo paradigma de Educación en la nube.

Fuente: Adaptación

propia del original de (Koutsopoulos & Kotsanis, 2014)

1.2. La Computación en la nube en el entorno educativo

rural

En

la literatura científica en torno a la aplicación o experiencias de utilización

de computación en la nube en el entorno rural o aislado destaca con fuerza su

utilización para dar respuesta a las necesidades específicas de la escuela

rural, de su profesorado, alumnado y familias. Las experiencias identificadas

en este campo se localizan en entornos diferentes al contexto europeo, por lo

que el concepto “escuela rural”, sus posibilidades y circunstancias, difieren

bastante de las de la escuela europea.

Son

múltiples las posibilidades y beneficios potenciales que esta tecnología

emergente puede proporcionar al mundo educativo rural, si están diseñados e

implementados de forma en que supongan un recurso fructífero para la comunidad

educativa a la par que económicamente ventajoso frente al modelo actual. Cuando

además la tecnología proporciona un puente para ayudar a superar la brecha

existente entre las escuelas más desfavorecidas por su falta de recursos o

aislamiento y la disponibilidad de conocimiento, infraestructura y soporte

tecnológico, las posibilidades son aún más prometedoras (Álvarez-

Álvarez & García-Prieto,

2021).

El

trabajo de los investigadores Dinesha y Agrawal (2011) presenta una propuesta de diseño y

aplicación de tecnologías en la nube para la mejora de la educación en las

áreas rurales desfavorecidas de la India. En este contexto, los autores

resaltan las circunstancias específicas de esa población, que sufre de unas

condiciones elevadas de pobreza, paro y falta de alfabetización, y se insiste

en que la mejora en la calidad de la educación es la clave para la mejora de

las condiciones de la comunidad rural en India. Las características de la

escuela rural, de acuerdo a Echazarra

y Radinger (2019), se caracterizan, entre otros

elementos, por tener una mayor falta de infraestructuras y servicios que sus

equivalentes urbanos. En el caso de las escuelas rurales de algunas partes del

mundo, además, hay una carencia de profesorado cualificado (Kidwai

et al., 2013; Wang, & Wong, 2019), y el mismo demanda

contar con materiales educativos de calidad. Adicionalmente se suman otros

problemas estructurales, como resaltan los autores de la propuesta:

financiación escasa, pocas escuelas en áreas que exigen largos desplazamientos

diarios del alumnado y malas infraestructuras, aspectos también resaltados por

otros estudios recientes como los de Álvarez- Álvarez y García-Prieto

(2021) y Carrete-Marín y Domingo-Peñafiel, (2021).

La

propuesta tecnológica de Dinesha y Agrawal (2011) describe la utilización de soluciones de

computación en la nube que combinen la disponibilidad de Entornos Virtuales de

Aprendizaje (en este caso Moodle) con acceso a recursos y almacenamiento

virtualizado y acceso a ordenadores y equipos virtuales con diferentes

configuraciones y software a disposición de profesorado y alumnado rural. La

propuesta de almacenamiento está planteada para que pueda servir de repositorio

de referencia con materiales educativos de calidad para que los centros puedan

utilizarlos en sus clases, que tienen unas graves carencias de recursos

(bibliotecas o acceso a fuentes de información cercanas) y así poder dotar a

las escuelas a los recursos más avanzados, así como servir de repositorio en la

nube para todas sus necesidades de almacenamiento. Los modelos de uso de SaaS

(Software como Servicio) y IaS (Infraestructura como

Servicio) se presentan como muy adecuados para el contexto de la educación

rural. En concreto el uso de DSaaS (Almacenamiento de

Datos como Servicio) que permitiría crear una base de datos distribuida con una

red de recursos de alta calidad y una biblioteca digital a la que podrían

acceder de forma simultánea desde múltiples escuelas, con todo tipo de recursos

educativos: e-books, libros de texto, instrucciones, vídeos formativos, etc. El

modelo de Infraestructura como Servicio (IaaS) también proporcionaría a la

escuela rural servicios como videoconferencias con expertos o entre centros,

vídeos de referencia, juegos interactivos de aprendizaje, etc. con la

flexibilidad necesaria para acomodarse al nivel de demanda de cada momento, con

software y recursos siempre actualizados y que proporcionarían a la escuela

rural las oportunidades de las que carece en la actualidad. En este caso concreto,

la computación en la nube sería un elemento clave para poder proporcionar

recursos a toda la escuela rural, no tanto para dar servicio al alumnado de

forma individual, sino para conectar la escuela rural con el conocimiento y

recursos más avanzados en el estado o región, y así poder suplir sus carencias

estructurales. Como indican los autores, esta situación es algo posible puesto

que hay un interés creciente en dotar de las infraestructuras mínimas

(conexiones de banda ancha, dotación informática) a los centros rurales, y

poder proporcionar una formación de mayor calidad al alumnado rural, y así

mejorar el nivel educativo de la comunidad rural, lo que desembocaría en mejora

de oportunidades y empleabilidad y ayudaría a reducir los elevados índices de

pobreza en la zona.

Investigadores

como Sukanesh y Kanmani

(2014) proponen hacer un diseño de implementación de estas tecnologías en el

ámbito de la escuela rural teniendo en cuenta sus posibilidades y limitaciones

económicas y de formación entre otras, explorando con cautela la adopción de

estos conceptos y tecnologías para garantizar su mejor integración y beneficio

por parte de las comunidades educativas rurales. Así, la opción preferida en su

caso, localizado en escuelas de India, fue la de utilizar recursos gratuitos o

con un coste mínimo.

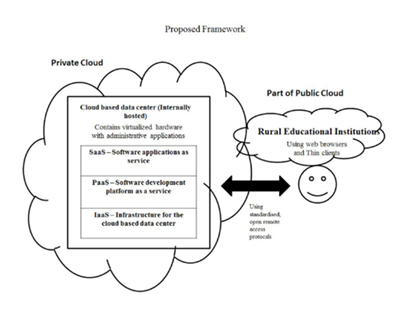

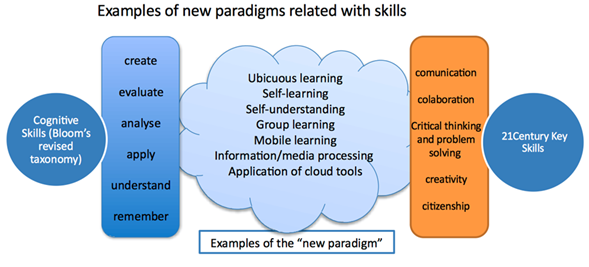

Arquitectura propuesta para la Nube Rural

Fuente: Sukanesh & Kanmani, (2014)

El

modelo de computación en la nube implementado por dichos autores para la

experiencia piloto "Nube Rural", como se describe en la figura 2, es

el de una nube híbrida, en la que una nube privada implementa los recursos

virtualizados principales, y otra pública conecta los centros educativos. Las

claves de esta experiencia para los autores son tres: la necesidad de potenciar

las áreas rurales para avanzar en el desarrollo, que en caso de India suponen

dos tercios de la población del país; el empoderamiento individual del alumnado

rural, que al tener más oportunidades de formación de calidad gracias a la

mejora de los recursos y soporte de la escuela rural, podrá competir en mejores

condiciones por un trabajo cualificado, sin sentirse “inferiores” a los que

acuden a centros urbanos; y por último, el papel de esta tecnología para

facilitar una educación de calidad a la población sin recursos económicos,

mucha de ella en el rural, dado que en la actualidad la mayoría de las familias

rurales no pueden permitirse que sus hijas e hijos vayan a estudiar a escuelas

en la ciudad por dificultades económicas.

En

Latinoamérica también encontramos referencias a la potencialidad de aplicación

de las tecnologías en la nube aplicadas a la escuela rural. La propuesta de Bayonet y Patiño (2014) explora las posibilidades del

“Mobile Cloud”, es decir, la combinación de la utilización de dispositivos

móviles y computación en la nube en el contexto de la escuela rural de

República Dominicana. De las potencialidades ya descritas anteriormente, estos

autores destacan el interés que supone el hecho de que el enorme despliegue de

dispositivos móviles (tanto en áreas rurales como urbanas) presente una

oportunidad muy interesante para las áreas rurales que no tienen una dotación

adecuada de infraestructuras terrestres de comunicaciones. La popularización y

el acceso más económico al móvil/tableta con datos puede proporcionar el acceso

al mundo de servicios y aplicaciones que viene de la mano de la computación en

la nube, donde la capacidad de cómputo y almacenamiento se ejecuta en remoto,

no en el terminal móvil. Éste, sin embargo, también tiene sus limitaciones,

tanto por el propio formato físico, más reducido que un ordenador, como por

limitaciones de ancho de banda o acceso concurrente que reduce la velocidad de

acceso a la información, además de las propias del entorno rural/aislado: mala

cobertura, conectividad intermitente, etc. (Vaidya,

et al., 2020). Esta limitación de la computación en la nube, es decir, la

“necesidad de estar conectado permanentemente” para poder acceder a recursos y

servicios educativos, puede ser complementada con herramientas que utilizan la

sincronización de los recursos en la nube con los equipos locales, como por

ejemplo sistemas de almacenamiento en la nube como Nextcloud

o Dropbox, que permiten poder trabajar en recursos en el equipo local para,

cuando cuenten con conexión, actualizar el recurso para tener la última versión

disponible. Algunas aplicaciones educativas como Moodle offline (LSMS, s.f.)

también son muy adecuadas para el contexto rural con dificultad de

conexión. Esta versión permite que el

profesorado del curso cree una instantánea del mismo,

y el alumnado tenga la posibilidad de conectarse al servidor cuando su conexión

a Internet esté disponible y descargar la instantánea del curso, para ser

utilizado sin conexión.

Otro

de los aspectos más valorados de esta tecnología es la posibilidad de acceso a

los recursos en la nube sin importar el sistema operativo móvil (IOS, Android,

etc.), “utilizando lenguajes estándares web y estándares como HTML/HTML5, CSS y

JavaScript permite funcionalidad multiplataforma y elimina las limitaciones de

desarrollo de aplicaciones nativas” (Bayonet &

Patiño, 2014), lo que abre una oportunidad tanto a proveedores y

desarrolladores como a instituciones educativas para proporcionar soluciones de

acceso y aplicaciones basadas en la nube para el sector educativo,

independientemente de dónde esté situado.

Una

experiencia de uso de “mobile cloud”,

en este caso utilizando iPads para sustituir el material impreso, y

beneficiarse del uso extendido de tecnologías y recursos en la nube, lo realizó

el Sint-Pieterscollege Blankenberge

en Bélgica desde el curso 2011-12. (CloudWATCH, s.

f.). La experiencia, que se fue ampliando en los años siguientes, supuso un

cambio metodológico en el centro, comenzando por el profesorado, que tuvo que

transformar sus métodos de enseñanza, en el que se realizó una transferencia de

todo el material de aprendizaje y tareas a través de la nube, y, según la

descripción del propio proyecto orientando su rol hacia la guía y tutorización

en un aprendizaje más autónomo de su alumnado.

1.3. El entorno tecnológico desarrollado en el proyecto

"RuralSchoolCloud"

Nuestra

investigación se apoyó en el análisis de los desarrollos y estudios previos

existentes en el contexto internacional y, teniendo en cuenta los resultados y

lecciones aprendidas, permitió construir y testar una solución a medida basada

en tecnologías de computación en la nube y software de código abierto, que

fuese útil y potente para proporcionar los mejores servicios y recursos para

dar soporte a experiencias de aprendizaje y colaboración entre escuelas rurales

y dispersas en Europa. Esta solución debería tener una gran facilidad de uso, a

la vez que ser flexible para dar respuesta a futuras necesidades y que tuviese

una utilidad clara y concreta para los usuarios finales, teniendo en cuenta

también los condicionantes económicos para que pudiese ser adoptado por las

comunidades educativas rurales europeas.

El

entorno educativo RuralSchoolCloud (RSC) se diseñó a

partir de un análisis previo de necesidades de las escuelas rurales europeas

participantes y sobre la base de las experiencias previas positivas del equipo

de investigación en otros proyectos precursores como “Rede de Escolas na Nube” y “Rural School Communities for Education in the Cloud”. En este caso se trataba de diseñar un entorno

al que acceder de forma segura mediante una identificación individual, a través

de un navegador web y un escritorio en la nube con un conjunto de servicios y

funcionalidades personalizables para docentes y alumnado de las escuelas

rurales europeas. Este escritorio en la nube sería principalmente una

herramienta colaborativa para actividades comunes entre profesorado y alumnado

y entre las escuelas rurales participantes.

El

entorno educativo RSC ofrecía al profesorado y alumnado la posibilidad de:

·

Acceder desde cualquier dispositivo con capacidad web,

desde cualquier sistema operativo: PC, antiguo o nuevo, tabletas, teléfonos

inteligentes, encerados digitales interactivos (EDI), Smart TV, etc. en

cualquier momento y desde cualquier lugar: escuela, casa, biblioteca,

cibercafé...

·

Tener su propia área privada donde cargar recursos,

trabajar en programas basados en la nube (ofimática, multimedia, etc.) para

crear contenido, almacenarlo, etc.

·

Compartir archivos con otras personas de la escuela

(profesorado y alumnado), para trabajar juntos de forma asíncrona o sincrónica

en ellos.

·

Disponer de distintos niveles de comunicación para

contactar y trabajar de distintas formas con otros usuarios (profesorado y

alumnado) en la nube, de forma sencilla, asincrónica o sincrónica.

El

profesorado, además, podía gestionar el acceso de su alumnado a los recursos de

forma autónoma, sin necesidad de depender de un soporte técnico, así como

monitorizar su progreso y proporcionar retroalimentación de diferentes maneras.

Un docente designado (con rol de "administrador/a de la nube")

también podía personalizar y añadir nuevos recursos y herramientas disponibles

para un grupo de estudiantes (y/o profesores) en el escritorio en la nube en

cualquier momento, o administrar sus cuentas de usuario.

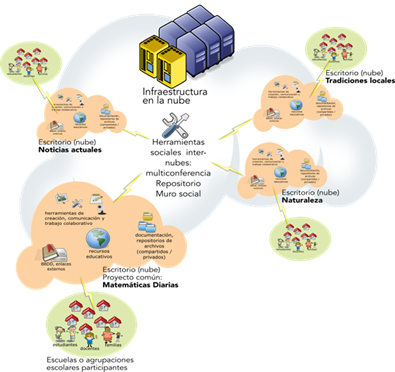

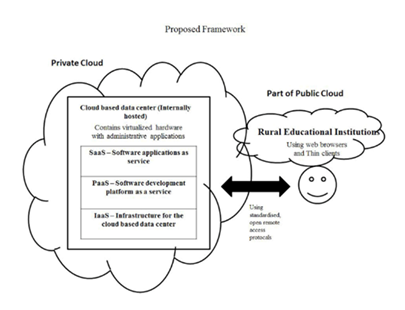

Esquema funcional del Entorno Educativo RSC

En la

figura 3 se describe cómo se planteó el entorno educativo de computación en la

nube de nuestro proyecto de investigación, donde se diseñó una propuesta

pedagógica basada en la colaboración y en la interdisciplinariedad, siguiendo

la metodología de trabajo por proyectos. Este diseño dio respuesta a las

diferentes comunidades escolares implicadas en el piloto, que se agruparon en

torno a cuatro grandes temáticas comunes: Naturaleza, Noticias actuales,

Matemáticas diarias y Tradiciones locales. Sobre una base de infraestructura de

computación en la nube, que gestionaba el Centro de Supercomputación de

Galicia, se desarrollaron cuatro escritorios virtuales interconectados (que por

simplificar denominaremos “nubes”) que compartían un conjunto de herramientas sociales

que permitían interactuar a nivel local, nacional y trasnacional a todos los

miembros de la comunidad europea implicados en los proyectos colaborativos.

Cada nube contaba con una serie de recursos de creación de materiales,

comunicación y trabajo colaborativo, servicio de videoconferencia, repositorios

de documentación compartida para el proyecto o individual, recursos educativos

adaptados y seleccionados por los participantes y enlaces externos a otras

herramientas y servicios en la nube.

2. Metodología

2.1 Objetivos de la investigación

El

objetivo general de la investigación se centró en diseñar, implementar y

evaluar un entorno para la enseñanza flexible y la colaboración en centros

educativos rurales basado en la tecnología de computación en la nube. Este a su

vez se desdobló en otros seis objetivos específicos que guiaron la

investigación:

1. Analizar las

necesidades de las escuelas rurales europeas para mejorar la colaboración y la

flexibilización de los procesos educativos.

2. Explorar las

posibilidades de la computación en la nube en la escuela rural.

3. Diseñar un entorno

para la enseñanza flexible y para la colaboración basada en la computación en

la nube.

4. Experimentar una

solución basada en computación en la nube en escuelas rurales europeas.

5. Analizar el

impacto de la utilización de la computación en la nube en el alumnado y

profesorado (actitudes, destrezas y competencias, usos en los procesos

formativos).

6. Analizar las estrategias

didácticas, recursos educativos desarrollados y actividades surgidas en el

marco de las experiencias piloto del proyecto RuralSchoolCloud.

7. Analizar la

repercusión de la computación en la nube en la mejora de la coordinación entre

docentes y en la gestión escolar.

8. Analizar las

posibilidades de la computación en la nube, como medio innovador para facilitar

el aprendizaje flexible y significativo en contextos educativos.

2.1. Diseño

Se

realizó una Investigación Basada en Diseño (IBD) al considerar que las

características de esta metodología: pragmática, iterativa, contextual, situada

(Wang & Hannafin, 2005) se ajustaban de forma

óptima a los objetivos y resultados esperados del proyecto RuralSchoolCloud.

La investigación se desarrolló en 4 fases siguiendo la estructura de McKenney y Reeves (2013) y se combinaron instrumentos

cualitativos (evidencias documentales –materiales didácticos, producciones

educativas, entrevistas, revisión de expertos) y cuantitativos (cuestionarios a

alumnado y profesorado, analíticas de seguimiento del sistema).

Figura 4

Fases de la investigación RSC

Fuente: Rodríguez-Malmierca

(2022)

2.3. Muestra

La población

objeto de estudio estaba integrada por el total de alumnado y profesorado de

las 14 escuelas rurales participantes en el proyecto RSC localizadas en cinco

países europeos (Dinamarca, España, Gran Bretaña, Italia, Grecia). Dadas las

características del proyecto y las dificultades de acceso a la población para

realizar una experimentación transnacional se aplicó un muestreo intencional no

probabilístico. Finalmente, participaron en el piloto 560 estudiantes

(Dinamarca 30; España: 291; Grecia: 39; Italia: 90; y Reino Unido: 110) y 72

docentes (Dinamarca: 4; España: 47; Grecia: 4; Italia: 11; y Reino Unido: 6) de

los niveles de Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria Obligatoria.

Evaluación de la Plataforma por el profesorado RSC:

dimensiones de análisis

La validación de este instrumento se realizó mediante la

técnica de juicio de expertos y la fiabilidad del instrumento se contrastó a

través del coeficiente de consistencia interna Alfa de Cronbach alcanzando un

valor global α =0,96.

Los resultados obtenidos con este instrumento ayudaron

valorar, desde el punto de vista de los docentes, en qué medida la solución

técnica implementada fue adecuada a las necesidades de las escuelas durante el

piloto, así como identificar las necesidades y los ajustes necesarios que

debíamos considerar en la versión final del entorno.

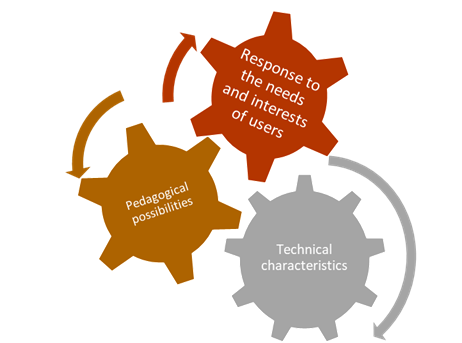

3. Análisis y resultados

Como ya se ha indicado, para dar respuesta a los

objetivos se recogieron datos a lo largo de las 4 fases de la investigación y a

través de 8 instrumentos diferentes. En este artículo se presentan los

principales resultados obtenidos respecto a la valoración por el profesorado de

las características técnicas y pedagógicas del entorno RSC de computación en la

nube desarrollado en el proyecto RuralSchoolCloud.

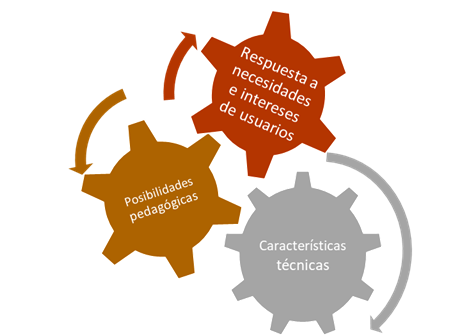

Dicha valoración se obtuvo mediante la aplicación del "Cuestionario de

análisis del entorno educativo RSC de computación en la nube" desarrollado

ad-hoc para el proyecto y configurado en torno a tres dimensiones reflejadas en

la figura 5 y 18 ítems (escalas likert), que nos

permitieron valorar tanto la usabilidad como el alineamiento del entorno con

las necesidades de los destinatarios:

Docentes que contestaron el cuestionario sobre el

entorno educativo RSC

|

PAÍS |

N. 61 |

GÉNERO |

EDAD MEDIA |

AÑOS DE

EXPERIENCIA |

ENSEÑANZA |

|||

|

Fem. |

Masc. |

Infantil |

Primaria |

Secundaria |

||||

|

DINAMARCA |

2 |

100,0% |

0,0% |

47 años |

18,0 años |

0,0% |

50,0% |

50,0% |

|

ESPAÑA |

44 |

93,2% |

6,8% |

30,3 años |

13,0 años |

65,9% |

34,1% |

0,0% |

|

GRECIA |

2 |

0,0% |

100,0% |

43 años |

18,5 años |

0,0% |

0,0% |

100,0% |

|

ITALIA |

4 |

75,0% |

25,0% |

41,2 años |

15,5 años |

0,0% |

50,0% |

50,0% |

|

REINO

UNIDO |

9 |

66,7% |

33,3% |

39 años |

10,1 años |

0,0% |

100,0% |

0,0% |

|

TOTAL |

61 |

85,2% |

14,8% |

40,1 años |

15, años |

47,5% |

44,3% |

8,2% |

Como se puede apreciar, el profesorado que participó en

el piloto y evaluó en entorno RSC eran mayoritariamente mujeres (85,2%) con una

edad media de 40,1 años y una media de 15 años de experiencia docente. En

cuanto su distribución por niveles educativos un 47,5% de profesorado de

Educación Infantil, un 44,3% de Educación Primaria y un 8,2% de Educación

Secundaria Obligatoria. Se obtuvieron datos de docentes de todos los países

implicados en el piloto: Dinamarca 5,5%; España: 65,2%; Grecia: 5,5%; Italia:

15,2%; y Reino Unido: 8,3.

3.1. Dimensión 1. Características técnicas del entorno

educativo RSC

Esta dimensión se centró en las características

técnicas del entorno educativo RSC que el profesorado había experimentado

durante los meses del piloto. Concretamente los elementos de análisis fueron:

idoneidad funcional (grado de flexibilidad de la comunicación) y usabilidad,

eficiencia, capacidad de aprendizaje, memorización, error y satisfacción (Nielsen, 1995) con el fin de conocer las opiniones del

profesorado participante sobre la usabilidad de la plataforma desarrollada.

En lo referido a la usabilidad del entorno educativo

RSC, se formularon con cinco ítems (escala Likert) respecto a las cuales se

pedía al profesorado que indicase el grado de acuerdo con las mismas. El

profesorado asignó valores altos en todos los ítems, como se puede apreciar en

la tabla 2. La media de todos los elementos relacionados con la categoría de

usabilidad es de 3.63 sobre 5. Las valoraciones más altas se otorgaron, en este

orden, a su facilidad para el uso de las diferentes funcionalidades (3,75) a su

aspecto atractivo para el profesorado (3,7), la facilidad para aprender el uso

de las diferentes funcionalidades de la misma (3,66),

así como a que pudieron realizar de forma efectiva tareas y alcanzar sus

objetivos con el entorno (3,64). Una puntuación menor, aun dentro de una

valoración bastante positiva, obtuvo el ítem relativo a la configuración del

entorno y su potencial de apoyo al profesorado de manera que no cometía errores

a menudo (3,41).

Usabilidad del entorno educativo RSC

|

Usabilidad del entorno RSC |

Media |

Desv. |

Mín. |

Máx. |

|

Fue fácil aprender a usar las diferentes funcionalidades del entorno

educativo en la nube RSC |

3,66 |

0,75 |

2 |

5 |

|

Pude realizar de forma efectiva tareas y alcanzar mis objetivos con el

entorno educativo en la nube RSC |

3,64 |

0,86 |

2 |

5 |

|

Fue fácil recordar cómo usar las diferentes funcionalidades del entorno

educativo en la nube RSC |

3,75 |

0,9 |

1 |

5 |

|

Me pareció agradable la interfaz del entorno educativo en la nube

RSC |

3,7 |

0,92 |

1 |

5 |

|

El entorno educativo en la nube RSC me apoyó de manera que no cometía

errores a menudo |

3,41 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

|

Puntuación global sobre 5 |

3,63 |

0,75 |

2 |

5 |

Se puede afirmar que se cumplió el objetivo de conseguir

un entorno de aprendizaje de uso intuitivo, en el que la curva de aprendizaje

fue lo suficientemente suave para permitir una aproximación segura y sin

errores o un grado de frustración que impidiese la exploración de las

posibilidades del entorno. La búsqueda de la sencillez es una de las tendencias

actuales del ámbito informático de que reconocen investigadores del campo de la

tecnología educativa como Salinas (2013) para ajustarse a las necesidades de

los usuarios.

3.2. Dimensión 2. Posibilidades pedagógicas del

entorno educativo RSC

En lo relativo a las posibilidades pedagógicas del

entorno educativo RSC, referidas al uso del entorno para la colaboración,

vinculación con las comunidades locales e innovación pedagógica, el

cuestionario incluía otros cinco ítems en los que se pedía al profesorado que

indicase el grado de acuerdo. Los resultados apuntaron un nivel mayoritario de

acuerdo del profesorado respecto a la utilidad e idoneidad del entorno

educativo en la nube para estas tareas.

Si se observa en detalle las respuestas del

profesorado por cada elemento de esta dimensión, el ítem que obtiene una media

más alta es “la utilización del entorno RSC motivó cambios en mi aula y en mi

práctica profesional (planificación de actividades, gestión escolar,

preparación de recursos, etc.)”. En este ítem, el 45,9% del profesorado expresó

estar totalmente de acuerdo o muy de acuerdo, frente a solo un 19,7% que indicó

estar en desacuerdo o muy en desacuerdo. El 34,4% del profesorado indicó una

respuesta neutra. Este resultado, teniendo en cuenta todos los condicionantes

que tiene un proyecto de esta naturaleza y los diferentes perfiles del

profesorado participante nos lleva a ser moderadamente optimistas ante las

posibilidades futuras de un entorno educativo de estas características aplicado

a la escuela rural. Por tanto, el entorno educativo RSC cumplió el objetivo de

proporcionar un elemento positivo de interacción y referencia educativa entre

las escuelas y las familias del alumnado participante. En algún caso, el

profesorado destacó la importancia de participar en proyectos de esta

naturaleza por la visibilidad mediática que despiertan, lo que redunda en una

visión positiva de la escuela ante las familias y la comunidad local. Hay que

recordar que estas escuelas, ante la despoblación del rural, tienen una

matrícula reducida y, a veces, tienen que competir con otro tipo de escuelas en

ciudades próximas que agrupan a alumnado de la zona, por lo que elementos que

supongan una revalorización de la escuela son vistas como muy positivos para

asegurar su supervivencia.

Tabla 3

Posibilidades pedagógicas entorno educativo RSC

|

|

Media |

Desv. |

Mín. |

Máx. |

|

La utilización del entorno

RSC motivó cambios en mi aula y en mi práctica profesional (planificación de

actividades, gestión escolar, preparación de recursos, etc.) |

3,38 |

1,083 |

1 |

5 |

|

Pude crear y actualizar

fácilmente los contenidos educativos con el entorno RSC |

3,25 |

1,135 |

1 |

5 |

|

El entorno RSC me permitió

reforzar los lazos entre la escuela y las familias |

3,21 |

1,280 |

1 |

5 |

|

Mis estudiantes y yo pudimos

compartir fácilmente contenidos educativos multimedia (imagen, sonido,

videos) con las funcionalidades del entorno educativo RSC: muros del

profesorado y alumnado |

3,11 |

1,404 |

1 |

5 |

|

Utilicé el entorno educativo

RSC para crear recursos educativos de forma colaborativa con otros/as |

3,08 |

1,308 |

1 |

5 |

|

Medias totales |

3,28 |

0,98 |

1,75 |

5 |

3.2. Dimensión 3.

Adecuación del entorno educativo RSC a las necesidades e intereses de

los usuarios

Finalmente nos centramos en la adecuación del entorno educativo

en la nube a las características e intereses de la comunidad usuaria,

concretamente en relación con el perfil de su alumnado, requisitos curriculares

de los centros, objetivos pedagógicos del profesorado y necesidades específicas

de la escuela rural. Los resultados muestran que el profesorado participante

mayoritariamente refiere que el entorno educativo en la nube diseñado e

implementado para el proyecto RuralSchoolCloud es

adecuado, situándose todas las puntuaciones medias por encima de 3 en la escala

de 5.

En esta última dimensión también son mayoritarias las

respuestas positivas por parte del profesorado, habiendo mayor diversidad en

las respuestas, teniendo en cuenta las diferentes tipologías de escuelas

participantes, puesto que varias de ellas incluían alumnado de corta edad (por

ejemplo, los CRAs participantes de España, con

alumnado de 3 a 7 años) y aunque dar respuesta al grupo de educación infantil

no fue seleccionado entre los objetivos del proyecto, sí hubiese sido necesaria

una adaptación mayor del entorno para el alumnado de corta edad, cuestión que,

por limitaciones del tiempo y por las tareas de desarrollo a realizar, no se

pudo abordar, optándose por una interfaz genérica para el alumnado de primaria

y secundaria, solo personalizada por los recursos y herramientas propuestos por

el profesorado participante.

Tabla 4

Adecuación del

entorno educativo RSC al usuario/a

|

|

Media |

Desv. |

Mín. |

Máx. |

|

El entorno RSC está adaptado

al perfil de mi alumnado (edad, perfil sociocultural, habilidades, etc.) |

3.05 |

1.38 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

|

El entorno RSC está adaptado

a mis objetivos de enseñanza |

3.28 |

1.21 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

|

El entorno RSC está adaptado

a las necesidades de escuelas rurales |

3.57 |

1.10 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

|

El entorno RSC está adaptado

a la infraestructura de las escuelas rurales |

3.57 |

1.07 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

|

Puntuación global sobre 5 |

3.37 |

1.05 |

1.00 |

5.00 |

Las cuestiones relacionadas con su adaptación a las

necesidades e infraestructura de las escuelas rurales tienen puntuaciones

medias superiores, apuntando así que se consiguió el objetivo planteado de que

el entorno educativo RSC estuviese adaptado a las necesidades de la escuela

rural, en cuanto a adecuación a las infraestructuras existentes y respuesta a

las necesidades percibidas en cuanto a funcionalidades por el profesorado

participante, así como a su infraestructura disponible.

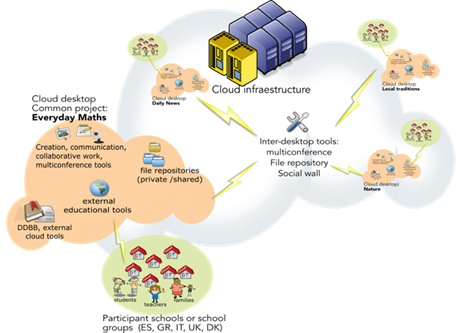

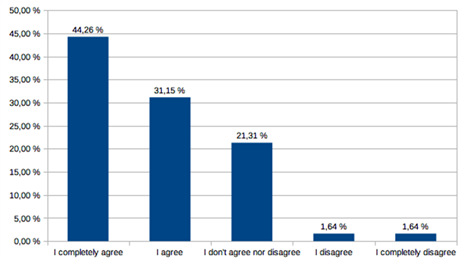

Por último, se pidió al profesorado participante que

indicasen si les gustaría seguir utilizando un entorno de aplicaciones en

computación en la nube en el futuro, en otros cursos o actividades, y la

inmensa mayoría (75,4%) estuvo de acuerdo o totalmente de acuerdo con esta posibilidad.

Solo un 3,24% del profesorado participante se mostró en desacuerdo o total

desacuerdo con la misma.

Figura 6

Intención de uso

futuro de aplicaciones en la nube por parte del profesorado

En

síntesis, según los resultados obtenidos y descritos previamente, el entorno

educativo RSC demostró ser una herramienta potente para proporcionar un recurso

educativo técnico funcional y utilizable para las escuelas rurales de la UE,

permitiendo flexibilidad temporal y espacial en las interacciones de profesores

y estudiantes, y proporcionando una herramienta adaptada a las diferentes

características, necesidades e intereses de las escuelas rurales.

Como

conclusión, el entorno educativo proporcionado en el proyecto RSC ofrecía

oportunidades para mejorar la calidad del aprendizaje y la enseñanza y mejorar

la innovación pedagógica en la educación de las escuelas rurales de la UE. La

mejora de la interacción entre el profesorado y alumnado con plataformas TIC

adaptadas a las necesidades y perfiles de sus usuarios para conseguir este

aprendizaje se ha señalado como una de las claves que intervienen en el proceso

de aprendizaje (Assaf-Silva, 2020).

El

profesorado participante indicó las siguientes posibilidades de mejora del

entorno educativo RSC que fueron incorporadas en los principios de diseño y

forman parte ya de las directrices a tener en cuenta

en los proyectos de investigación y líneas de futuro derivados de este trabajo:

·

Proporcionar mayor orientación: para fomentar la

implementación de escenarios educativos colaborativos, puede ser útil orientar,

apoyar y coordinar aún más a los docentes locales en el proceso de establecer

contactos entre sí, definir proyectos adaptados a sus objetivos curriculares,

planificar y organizar actividades comunes que se pueden mejorar a través de

las funcionalidades de la nube.

·

Uso de aplicaciones de código abierto ya existentes:

como se mencionó anteriormente, las herramientas existentes con las que

maestros y estudiantes ya estaban familiarizados podrían integrarse con la

plataforma para respaldar sus proyectos educativos.

·

Involucrar a las comunidades locales en las

actividades de la nube: esto podría hacerse permitiendo que algunas secciones y

recursos de la nube fueran accesibles a audiencias externas, y fomentando

escenarios educativos que integren a los diferentes actores de la comunidad

educativa (por ejemplo, familias, instituciones culturales, autoridades

locales).

·

Sería interesante realizar un análisis más profundo de

las diferencias de utilización de estas tecnologías de

acuerdo a parámetros como país, género o edad. Algunos estudios, como el

de Wang y Wong (2019), muestran unas diferencias significativas en aspectos

como el de género.

5. Financiación

La

investigación se enmarca en el Proyecto europeo competitivo: Comenius

Multilateral RuralSchoolCloud (Ref: 40182-LLP-1-2013-1-ES-COMENIUS-CMP), financiado por la

Comisión Europea -EACEA-.

Cloud Computing

and Open Source Software for European Rural Schools

1.

Introduction

Although there are multiple definitions of cloud

computing, one of the most accepted in the technological field is the one

proposed by NIST:

"Cloud computing is a model for enabling

ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand access to a range of configurable computing

resources (e.g. networks, servers, storage, applications and services) that can

be provided and put into operation with minimal management effort or service

provider intervention." (Mell & Grance, 2011)

This definition insists on the idea of simplicity (or

minimal intervention) of agents other than the end user to have these computing

resources at one’s disposal, like the metaphor of the electricity grid where

computing resources are provided in a simple and transparent way. (Carr, 2009)

It sometimes seems difficult to distinguish the

boundary between what is understood as opportunities of cloud computing for

schools and the possibilities of the Internet or the connected school (Magro,

2015). For this purpose, in the scientific literature there are some voices and

initiatives such as Katz (2008) or Qasem et al. (2019) highlighting the

potential of the cloud computing ecosystem as a unique opportunity to access

educational resources en masse and reuse them from large heterogeneous

repositories or cloud federations for educational purposes, providing us with a

base of universally accessible knowledge.

1.1. Cloud computing at school

Rapid technological evolution and its services require

a constant effort to provide the school with mechanisms to provide software and

hardware to fit its needs (Sharma, Gupta, & Acharya, 2020). Researchers from the Hellenic American

University (Kalagiakos & Karampelas, 2011) highlighted the need for the

global educational community to benefit from the movement of open educational

content, and that thanks to cloud computing these can be easily integrated by

educators from anywhere in the world. Thus, it is criticised that repositories

of open learning objects, such as the one promoted by the OpenCourseWare

Consortium, do not follow standards to encourage their reuse or the integration

of their valuable learning resources in a cloud infrastructure, through the

development of an Educational Operating System in the Cloud to facilitate their

management. They therefore propose an initiative called the "Federation of

Open Educational Cloud Computing" (FOECC) that enables simple reuse of

educational materials by any institution among different systems in the cloud,

once problems regarding system portability and interoperability have been

identified and solved. These difficulties do not lie fundamentally in the

technical aspects, but in the determination of the different institutional and

political actors.

In a future scenario, Sasikala and Prema (2010)

propose the design and deployment of a Massive and Centralised Cloud Computing

for Education (MCCC). With this model, teachers and students would have access

to resources at any time and from any location, offering applications and

services for the entire educational community with their own selection of

applications and services. The centralised storage model means, among other

advantages, that the loss of individual elements. For example, if a laptop that

stores notes is lost, it is not a serious incident and the monitoring of the

use of resources is easier for the institution (which on the other hand can be

a very delicate point because it entails loss of privacy).

The concept of "the cloud" at the heart of

this new reality of our lives and its role in the school environment leads

Koutsopoulos and Kotsanis (2014) to present a vision in which teaching-learning

processes will be focused on the "student-centred" (cloud

student-centred) in a framework of not only technological, but organizational

integration where all the agents present in education (students, teachers,

administration, family, community) assume a more integrated and present

function. In that vision, this technology provides a step beyond the constructivist

approach to learning, where technology is more than a set of simple tools and

students actively participate in the educational process in a way that helps

them build their own learning (Jonassen et al., 1998).

In this new paradigm of learning, hand in hand with

cloud computing, Koutsopoulos and Kotsanis (2014) assert the need to address

the eight key competences of the European Framework of Competences of Lifelong

Learning (European Commission, 2019), defined as the combination of knowledge,

skills and attitudes that as individuals we need for personal development,

active citizenship, social inclusion and employment. It also responds to the

need of students to acquire the key skills, attitudes and qualities of the

twenty-first century, as described in Figure 1.

Examples of a new paradigm of

Cloud Education.

Source: Adaptation of the original by Koutsopoulos & Kotsanis (2014)

1.2. Cloud computing in the

rural educational environment

In the scientific literature

on the application or experiences of using cloud computing in the rural or

isolated environment, what stands out is its use to respond to the specific

needs of the rural school, its teachers, students and families. The experiences

identified in this field belong to environments different from ones in the

European context, so the concept of "rural school", its possibilities

and circumstances, differs considerably from those of the European school.

There are multiple

possibilities and potential benefits that this emerging technology can provide

to the rural educational world, if they are designed and implemented in a way

that represents a fruitful resource for the educational community while being

economically advantageous compared to the current model. When technology also

helps bridge the gap between the most disadvantaged schools due to their lack

of resources or isolation and the availability of knowledge, infrastructure and

technological support, the possibilities are even more promising

(Álvarez-Álvarez & García-Prieto, 2021).

Researchers Dinesha and

Agrawal (2011) present a proposal for the design and application of cloud

technologies for the improvement of education in disadvantaged rural areas of

India. In this context, the authors highlight the specific circumstances of

this population, which suffers from high rates of poverty, unemployment and

lack of literacy, and insist that the improvement in the quality of education

is the key to improving the conditions of the rural community in India. The

characteristics of the rural school, according to Echazarra and Radinger

(2019), are characterised, among other elements, by having a greater lack of

infrastructure and services than their urban counterparts. In the case of rural

schools in some parts of the world, there is also a lack of qualified teachers

(Kidwai et al., 2013; Wang, & Wong,

2019), and the same demand for quality educational materials. The authors also

highlight additional structural problems of the proposal: scarce funding, few

schools in areas that require students to make long daily trips and poor

infrastructure. These aspects have also been stressed by other recent

studies such as those by Álvarez-Álvarez

& García-Prieto (2021) and Carrete-Marín,

& Domingo-Peñafiel, (2021).

The technological proposal of

Dinesha and Agrawal (2011) describes the use of cloud computing solutions

combining the availability of Virtual Learning Environments (in this case

Moodle) with access to resources and virtualised storage and access to

computers and virtual teams with different configurations and software

available to teachers and rural students. The storage proposal is suggested so

that it can serve as a reference repository with quality educational materials

so that schools can use them in their classes, which have serious lack of resources

(libraries or access to nearby sources of information). Thus , they are able to

provide schools with the most advanced resources, as well as serve as a cloud

repository for all their storage needs. SaaS (Software as a Service) and IaS

(Infrastructure as a Service) are presented as very suitable in the context of

rural education. In particular, the use of DSaaS (Data Storage as a Service)

would allow the creation of a distributed database with a network of

high-quality resources and a digital library that could be accessed

simultaneously from multiple schools, with all kinds of educational resources:

e-books, textbooks, instructions, training videos, etc. The Infrastructure as a

Service (IaaS) model would also provide the rural school with services such as

videoconferencing with experts or between centres, reference videos,

interactive learning games, etc. It is

flexible enough to constantly accommodate the level of demand, with up-to-date

software and resources that would provide the rural school with the

opportunities it currently lacks. In this specific case, cloud computing would

be a key element in providing resources for the entire rural school, not so

much to serve the students individually, but to connect the rural school with

the most advanced knowledge and resources in the state or region, and thus be

able to supply its structural deficiencies. As the authors point out, this

situation is somewhat possible since there is a growing interest in providing

the minimum infrastructures (broadband connections, computer equipment) to

rural centres as well as being able to provide higher quality training to rural

students. This in turn enriches the educational level of the rural community,

improving opportunities and employability while helping reduce the high rates

of poverty in the area.

Researchers such as Sukanesh

and Kanmani (2014) propose the implementation of these technologies in the

rural school taking into account their economic and training possibilities and

limitations, among others, cautiously exploring the adoption of these concepts

and technologies to guarantee their better integration and benefit in rural

educational communities. Consequently, the preferred option in this case,

located in schools in India, was to use free resources or with a minimum cost.

Proposed architecture for the

Rural Cloud

Source: Sukanesh

& Kanmani (2014)

The cloud computing model

implemented by these authors for the "Rural Cloud" pilot experience, as

described in Figure 2, is that of a hybrid cloud, in which a private cloud

deploys the main virtualised resources, and a public cloud connects the

educational centres. For the authors, the keys to this experience are

threefold: First, the need to enhance rural areas to advance in development,

which in the case of India account for two thirds of the country's population.

Secondly, the individual empowerment of rural students, who have more quality

training opportunities thanks to the improvement of resources and support of

the rural school. Thanks to which they will

be able to compete in better conditions for skilled work without feeling

"inferior" to those students from urban areas. Finally, the role of this

technology in providing quality education to the population without economic

resources, much of it in rural areas, given that currently most rural families

cannot afford to send children to schools in the city due to economic

difficulties.

In Latin America we also find

references to the potential for the application of cloud technologies applied

to rural schools. The proposal of Bayonet and Patiño (2014) explores the

possibilities of the "Mobile Cloud", that is, the combination of the

use of mobile devices and cloud computing in the context of rural schools in

the Dominican Republic. Of the potentials already described above, these

authors highlight the fact that the enormous deployment of mobile devices (both

in rural and urban areas) presents a very interesting opportunity for rural

areas that do not have an adequate endowment of land-based communication

infrastructures.

Popularisation and cheaper

access to the mobile/tablet with data can provide access to the world of

services and applications that comes hand in hand with cloud computing, where

computing and storage capacity runs remotely, not on the mobile terminal. This,

however, also has its limitations, both for the physical format itself, smaller

than a computer, and for limitations of bandwidth or concurrent access reducing

the speed of access to information, in addition to those of the rural /

isolated environment: poor coverage, intermittent connectivity, etc. (Vaidya, Shah, Virani, & Devadkar,

2020). This limitation of cloud

computing, that is, the "need to be permanently connected" in order

to access educational resources and services, can be complemented with tools

that use the synchronization of cloud resources with local computers, such as

cloud storage systems like Nextcloud or Dropbox. These systems allow you to

work on resources locally, and when connected, update the resources to the

latest version available. Some educational applications such as Moodle offline

(LSMS, n.d.) are also very suitable for rural areas with connection

difficulties. This version allows the

teaching staff of the course to create a snapshot and the students then have

the possibility to connect to the server when their Internet connection is

available and download the snapshot of the course to be used offline.

Another of the most valued

aspects of this technology is the possibility of access to cloud resources

regardless of the mobile operating system (IOS, Android, etc.). "Using

standard web languages and standards such as HTML/HTML5, CSS and JavaScript

allows cross-platform functionality and eliminates the limitations of native

application development" ( Bayonet & Patiño, 2014), which opens up an

opportunity for both providers, developers and educational institutions to

provide access solutions and cloud-based applications for the education sector,

regardless of where it is located.

An experience of using the

"mobile cloud” using iPads to replace printed material and benefit from the

widespread use of technologies and resources in the cloud was carried out by

the Sint-Pieterscollege Blankenberge in Belgium during the 2011-12 academic

year. (CloudWATCH, n.d.). The experience, which was expanded in the following

years, meant a methodological change in the centre, starting with the teachers,

who had to modify their teaching methods. A transfer of all the learning

material and tasks was performed through the cloud, and according to the

description of the project itself, orienting its role towards guidance and

tutoring towards a more autonomous learning of its students.

1.3. The technological

environment developed in the "RuralSchoolCloud" project

Our research was based on the

analysis of previous developments and studies in the international context.

Considering the results and lessons learned, this allowed us to build and test

a customised solution based on cloud computing technologies and open-source

software. The solution was useful and

powerful enough to provide the best services and resources to support learning

experiences and collaboration between rural and dispersed schools in Europe.

This solution should be easy to use, while being flexible enough to respond to

future needs as well as having a clear and concrete utility for end users, also

taking into account the economic conditions so that it could be adopted by

rural European educational communities.

The RuralSchoolCloud (RSC)

educational environment was designed from a previous analysis of the needs of

the participating European rural schools and based on the positive previous

experiences of the research team in other precursor projects such as "Rede

de Escolas na Nube" ( Schools in the Cloud Network) and "Rural School

Communities for Education in the Cloud". In this case, it was a question

of designing an environment to be accessed securely through individual

identification, using a web browser and a cloud desktop with a set of

customizable services and functionalities for teachers and students at European

rural schools. This cloud desktop would be chiefly a collaborative tool for

common activities between teachers and students and among participating rural

schools.

The RSC educational

environment offered teachers and students:

·

Access from any device with

web capability, from any operating system: PCs (old or new), tablets,

smartphones, interactive digital waxes (EDI), Smart TVs, etc. at any time and

from anywhere: school, home, library, Internet café…

·

Their your own private area,

where they can upload resources, work on cloud-based programs (office

automation, multimedia, etc.) to create content, store it, etc.

·

The possibility of sharing

files with other people in the school (teachers and students) in order to work

together asynchronously or synchronously on them.

·

Different levels of

communication to contact and work in different ways with other users (teachers

and students) in the cloud, in a simple, asynchronous or synchronous way.

Teachers could also manage

their students' access to resources autonomously, without the need to rely on

technical support, as well as monitor their progress and provide feedback in

different ways. A designated teacher (with the role of "cloud

administrator") could also customise and add new resources and tools

available to a group of students (and/or teachers) on the cloud desktop at any

time or manage their user accounts.

Figure 3 describes how the educational environment of

cloud computing of our research project was proposed. In it, a pedagogical

proposal based on collaboration and interdisciplinarity was designed following

the methodology of work by projects. This design responded to the needs of the

different school communities involved in the pilot, which were grouped around

four major common themes: Nature, Current News, Daily Mathematics and Local

Traditions. Regarding cloud computing infrastructure, which was managed by the

Supercomputing Centre of Galicia, four interconnected virtual desktops were

developed (which to simplify we will call "clouds"). These “clouds”

shared a set of social tools allowing all the members of the European community

involved in collaborative projects to interact at local, national

and transnational level. Each cloud had a series of resources for material

creation, communication and collaborative work, videoconferencing service,

repositories of shared documentation for the project or individual, educational

resources adapted and selected by the participants and external links to other

tools and services in the cloud

Figure 3

Functional outline of the RSC Educational Environment

2. Methodology

2.1. Objectives of the research

The overall objective of the research

focused on designing, implementing and evaluating an environment for flexible

teaching and collaboration in rural schools based on cloud computing

technology. This in turn unfolded into six other specific objectives that

guided the research:

1.

To analyse the needs of

European rural schools to improve collaboration and flexibility of educational

processes.

2.

To explore the possibilities

of cloud computing in rural schools.

3.

To design an environment for

flexible teaching and collaboration based on cloud computing.

4.

To experiment with a solution

based on cloud computing in European rural schools.

5.

To analyse the impact of the

use of cloud computing on students and teachers (attitudes, skills and

competences, uses in training processes).

6.

To analyse the didactic

strategies, educational resources developed and activities arising within the

framework of the pilot experiences of the RuralSchoolCloud project.

7.

To analyse the impact of cloud

computing on improving coordination between teachers and school management.

8.

To analyse the possibilities

of cloud computing as a ground-breaking means to aid flexible and meaningful

learning in educational contexts.

2.2. Design

A Design-Based Research (DBR)

was carried out when considering that the

characteristics of this methodology: pragmatic, iterative, contextual, situated

(Wang & Hannafin, 2005) were optimally adjusted to the objectives and

expected results of the RuralSchoolCloud project. The research was developed in

4 phases following the structure of McKenney and Reeves (2013) and qualitative

instruments (documentary evidence – didactic materials, educational

productions, interviews, expert review) and quantitative (questionnaires to

students and teachers, analytical monitoring of the system) were combined.

Stages of RSC research

Source: Rodríguez-Malmierca (2022)

2.3. Sample

The population studied was made

up of the total number of students and teachers from the 14 rural schools

participating in the RSC project in five European countries (Denmark, Spain,

Great Britain, Italy and Greece). Given the

characteristics of the project and the difficulties of access to the population

to carry out a transnational experiment, an intentional non-probabilistic

sampling was applied. Finally, 560 students participated in the pilot (Denmark:

30; Spain: 291; Greece: 39; Italy: 90; and United Kingdom: 110) and 72 teachers

(Denmark: 4; Spain: 47; Greece: 4; Italy: 11; and United Kingdom: 6) from

Elementary, Primary and Compulsory Secondary.

3. Analysis and results

Figure 5

Assessment of the Platform by RSC teachers: dimensions of analysis

The validation of this instrument was carried out using the expert

judgement technique and the reliability of the instrument was contrasted

through Cronbach’s Alpha internal consistency coefficient, reaching an overall

value α = 0.96.

The results obtained with this instrument helped to assess, from the

teachers’ perspective to what extent the technical solution implemented was

appropriate to the needs of the schools during the pilot, as well as to

identify the needs and necessary adjustments that we should consider in the

final version of the environment.

As we can see, the teachers who participated in the pilot were mostly

women (85.2%) with an average age of 40.1 years and an average of 15 years’

teaching experience. As for its

distribution by educational levels, 47.5% of teachers were from Elementary

Education, 44.3% from Primary Education and 8.2% from Compulsory Secondary

Education. Data were obtained from

teachers from all the countries involved in the pilot: Denmark: 5.5%; Spain:

65.2%; Greece: 5.5%; Italy: 15.2%; and the United Kingdom: 8.3%.

Teachers who answered the

questionnaire on the RSC educational environment

|

COUNTRY |

N. 61 |

GENDER |

AVERAGE AGE |

YEARS OF

EXPERI-ENCE |

TEACHING LEVEL |

|||

|

Five. |

Men. |

Elementary |

Primary |

Secondary |

||||

|

DENMARK |

2 |

100,0% |

0,0% |

47 |

18.0 |

0,0% |

50,0% |

50,0% |

|

SPAIN |

44 |

93,2% |

6,8% |

30.3 |

13.0 |

65,9% |

34,1% |

0,0% |

|

GREECE |

2 |

0,0% |

100,0% |

43 |

18.5 |

0,0% |

0,0% |

100,0% |

|

ITALY |

4 |

75,0% |

25,0% |

41.2 |

15.5 |

0,0% |

50,0% |

50,0% |

|

UNITED KINGDOM |

9 |

66,7% |

33,3% |

39 |

10.1 |

0,0% |

100,0% |

0,0% |

|

TOTAL |

61 |

85,2% |

14,8% |

40.1 |

15 |

47,5% |

44,3% |

8,2% |

3.1.

Dimension 1. Technical characteristics of the RSC educational environment

This

dimension focused on the technical characteristics of the RSC educational environment

that teachers had experienced during the months of the pilot. Specifically, the

elements of analysis were functional suitability (degree of flexibility of

communication) and usability, efficiency, learning capacity, memorisation, error and satisfaction (Nielsen, 1995) in

order to know the opinions of the participating teachers on the usability of

the platform.

Usability

of the RSC educational environment was formulated with five items (Likert

scale) where teachers were asked to indicate to what degree the agreed with

them. Table 2 shows us that teaching staff assigned high values in all the

items. The average of all items related to the usability category is 3.63 out

of 5. The highest ratings were given, in

this order, to their ease of use of the different functionalities (3.75) to

their attractive appearance for teachers (3.7), the ease of learning the use of

the different functionalities of the platform (3.66). As well as that they were

able to effectively perform tasks and achieve their objectives with the

environment (3.64). A lower score, even within a fairly

positive assessment, was obtained by the item related to the

configuration of the environment and its potential to support teachers so that

they did not often make mistakes (3,41).

It

can be said that the objective of achieving an intuitive learning environment

was met, in which the learning curve was smooth enough to allow a safe and

error-free approach or a degree of frustration which would have prevented the

exploration of the possibilities of the environment. The search for simplicity

is one of the current trends in the field of I.T. and is acknowledged by

researchers in the field of educational technology such as Salinas (2013) who

underlines its importance in adjusting to the needs of users.

Table 2

Usability of the RSC

educational environment

|

Usability

of the RSC environment |

Average |

Dev. |

Min. |

Max. |

|

It was easy to learn how to use the different functionalities of the

educational environment in the RSC cloud |

3,66 |

0,75 |

2 |

5 |

|

I was able to effectively perform tasks and achieve my goals with the

RSC cloud education environment |

3,64 |

0,86 |

2 |

5 |

|

It was easy to remember how to use the different functionalities of

the educational environment in the RSC cloud |

3,75 |

0,9 |

1 |

5 |

|

I found the interface of the educational environment in the RSC cloud

pleasant |

3,7 |

0,92 |

1 |

5 |

|

The RSC cloud education environment supported me in such a way that I

didn't make mistakes often |

3,41 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

|

Overall rating out of 5 |

3,63 |

0,75 |

2 |

5 |

3.2.

Dimension 2. Pedagogical possibilities of the RSC educational environment

Regarding

the pedagogical possibilities of the RSC educational environment and with reference

to the use of the environment for collaboration, linkage with local communities

and pedagogical innovation, the questionnaire included five other items in

which teachers were asked to indicate the degree of agreement. The results suggested most teachers agreed

with the usefulness and suitability of the educational environment in the cloud

for these tasks.

If

we look in detail at the responses of teachers for each element of this

dimension, the item that obtains a higher average is "the use of the RSC

environment motivated changes in my classroom and in my professional practice

(planning of activities, school management, preparation of resources, etc.)

". In this item, 45.9% of teachers expressed total agreement or strong

agreement, compared to only 19.7% who said that they disagreed or strongly

disagreed. 34.4% of teachers gave a neutral response. This result, considering

all the conditions that a project of this nature has and the different profiles

of the participating teachers, leads us to be moderately optimistic about the

future possibilities of an educational environment with these features applied

to the rural school. Therefore, the RSC educational environment fulfilled the

objective of providing a positive element of interaction and educational

reference between the schools and the families of the participating students.

In some cases, the teaching staff highlighted the importance of participating

in projects of this nature due to media visibility, which results in families

and the local community looking positively upon the school. It should be

remembered that these schools, in the face of rural depopulation, have low

enrolment. At times they have to compete

with other types of schools in nearby cities that group students from the area,

so any elements which lead to a revaluation of the school are seen as

very positive to ensure their survival.

Pedagogical possibilities of

the RSC educational environment

|

|

Average |

Dev. |

Min. |

Max. |

|

The use of the RSC environment motivated changes in my classroom and

in my professional practice (activity planning, school management, resource

preparation, etc.) |

3,38 |

1,083 |

1 |

5 |

|

I was able to easily create and update educational content with the

RSC environment |

3,25 |

1,135 |

1 |

5 |

|

The RSC environment allowed me to strengthen the bonds between the

school and families |

3,21 |

1,280 |

1 |

5 |

|

My students and I were able to easily share multimedia educational

content (image, sound, videos) with the functionalities of the RSC

educational environment: walls of teachers and students |

3,11 |

1,404 |

1 |

5 |

|

I used the RSC educational environment to create educational resources

collaboratively with others |

3,08 |

1,308 |

1 |

5 |

|

Total averages |

3,28 |

0,98 |

1,75 |

5 |

3.2.

Dimension 3. Adaptation of the RSC