Revisión de la literatura sobre anotaciones de vídeo en

la formación docente

Literature review on video annotations in teacher education

Dra. Violeta Cebrián-Robles. Profesora Ayudante Doctor. Universidad

de Extremadura. España

Dra. Violeta Cebrián-Robles. Profesora Ayudante Doctor. Universidad

de Extremadura. España

Dra. Ana-Belén

Pérez-Torregrosa. Investigadora. Universidad de Málaga.

España

Dra. Ana-Belén

Pérez-Torregrosa. Investigadora. Universidad de Málaga.

España

Dr. Manuel Cebrián

de la Serna. Catedrático de Universidad. Universidad de

Málaga. España

Dr. Manuel Cebrián

de la Serna. Catedrático de Universidad. Universidad de

Málaga. España

Recibido: 2022/07/26

Revisado: 2022/09/01 Aceptado: 2022/11/09 Preprint: 2022/12/01

Publicado: 2023/01/07

Cómo citar este artículo:

Cebrián-Robles,

V., Pérez-Torregrosa, A. B., & Cebrián de la Serna, M. (2023). Revisión de

la literatura sobre anotaciones de vídeo en la formación docente [Literature

review on video annotations in teacher education]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 66, 31-57.

https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.95782

RESUMEN

Existe una tradición en el uso

de videos digitales en la formación del profesorado donde las anotaciones de

vídeo son una tecnología emergente que ofrece un uso más activo a los vídeos

disponibles en internet y los creados en las prácticas de aula. Sus

posibilidades técnicas consisten en crear anotaciones en los vídeos de forma

individual para el portafolios o compartida en grupos de clases y redes

profesionales. Como tecnología en evolución ofrece nuevas posibilidades para la

formación docente mediante etiquetado social e hipervínculos que pueden ser

analizados. El presente estudio es una revisión de la literatura reciente desde

2018 a 2022 sobre el uso de las anotaciones multimedia en la formación docente

mediante el protocolo PRISMA, seleccionando desde bases de datos (WOS, Scopus y

ERIC) 244 referencias que tras aplicar los criterios de exclusión e inclusión

se obtuvieron 25 referencias que aplican sólo en el tópico de la formación de

docentes. Se ofrece una lista de las plataformas más empleadas, los métodos de

investigación utilizados, el perfil de los participantes y los tópicos de

aplicación. Es compartida la utilidad de las anotaciones de video en la

formación de docentes especialmente para el análisis y reflexión sobre las

prácticas.

ABSTRACT

There is a tradition in the

use of digital video in teacher training where video annotations are an

emerging technology that offers a more active use of videos available on the

Internet and those created in classroom practices. Its technical possibilities are

to create annotations on videos individually for the portfolio or shared in

class groups and professional networks. As an evolving technology it offers new

possibilities for teacher training through social tagging and hyperlinks that

can be analyzed. The present study is a review of recent literature from 2018

to 2022 on the use of multimedia annotations in teacher education using

protocol PRISMA, selecting from databases (WOS, Scopus y ERIC) 244 references

that after applying exclusion and inclusion criteria we selected the 25

references that apply only in the topic of teacher education. A list of the

most used platforms, the research methods used, the profile of the participants

and the topics of application is provided. The usefulness of video annotations

in teacher training is shared, especially for analysis and reflection on

practices.

PALABRAS CLAVES · KEYWORDS

Formación del personal docente; Formación inicial de

docentes; formación de docentes en activo; vídeo digital; anotaciones de video.

Teacher training; initial teacher training; in-service

teacher training; digital video; video annotation

1. Introducción

La tendencia en el uso de los

formatos de vídeo en todos los niveles educativos era un tópico en auge antes

de la covid19, y con esta pandemia se ha visto incrementado exponencialmente su

producción con el uso de los sistemas de videoconferencia en una transición

rápida a una educación a distancia. El uso de videoconferencias durante la

pandemia por parte de docentes y estudiantes tuvo un gran éxito, pues la

educación no se paró gracias a ello. Sin embargo, en ocasiones este uso se

tornó en abuso, al encontrarnos tantas horas concentrados y mediados por una

pantalla. Por esta razón, y tras esta vivencia con doble resultado, ambos solicitan

una metodología más dinámica y activa en el uso de la videoconferencia, como

una utilización de los vídeos como recursos con mayor calidad, interactividad y

motivación para la enseñanza que los producidos por esta excepcionalidad vivida

por todos.

El video como recurso y

tecnología venía aplicándose en todas las áreas, siendo en la educación

universitaria y en la formación de los grados en educación un tema muy

desarrollado (Bayram, 2012; Arya et al., 2014; Nielsen, 2015; Gallego-Arrufat,

2015; Chui-Lami & Habil, 2021). Donde encontramos muchos ejemplos en el uso

de los videos en la formación inicial como permanente de los docentes en las

distintas temáticas como la enseñanza de las matemáticas (Barth-Cohen, 2018),

la enseñanza de las ciencias (Luna & Sherin, 2017), las tutorías y

prácticas externas en la Universidad-Centro de prácticas (Youens et al., 2014),

como la identidad profesional bajo autobiografías en vídeo (Ó Gallchóir et al.,

2018), entre otros. Siendo bastante nueva la utilización de las anotaciones de

video (en adelante, AV) dentro de la formación permanente y mediante la

creación de comunidades y redes profesionales (Ruiz-Rey et al., 2021a).

En un intento de romper la

linealidad de la secuencia de vídeo y dotarlo de mayor interactividad, las tecnologías

de anotaciones multimedia están proporcionando una mejor y fácil utilización de

los vídeos en la enseñanza de todos los niveles, especialmente en aquellos que

más se han experimentado como es en la educación superior (Cebrián-de-la-Serna

et al., 2015; Cebrián-Robles et al., 2016; Po-Sheng et al., 2018; Marçal et

al., 2020; Hefter & Berthold, 2020; Ruiz-Rey et al., 2021b; Mei-Po et al.,

2021), donde en la formación de docentes está retomando un enfoque más

innovador, flexible y creativo que salva las críticas encontradas en los

enfoques de microteaching del pasado, por cuanto que, se ofrece como recurso y

herramienta en mano de los propios docentes para la formación inicial y

permanente y la modalidad que éstos decidan. Dentro de la primera, la formación

inicial tenemos una revisión interesante sobre las anotaciones de vídeo en

Pérez-Torregrosa et al. (2017). Vamos a exponer a continuación un desarrollo

tanto tecnológico como metodológico de las anotaciones multimedia en general y

del vídeo en particular.

Las anotaciones de video (AV)

en la formación de docentes

El video como soporte y

recurso en la formación de docentes recoge en la literatura especializada una importante

magnitud numérica como versatilidad de usos, que ha evolucionado paralelamente

a la transformación digital, transitando desde las primeras cintas magnéticas

hasta el vídeo digital, con una diversidad de prácticas y modelos pedagógicos

que facilitó acuñar una profusión de términos propios. Son ejemplos de esta

prodigalidad las siguientes denominaciones: píldoras de

aprendizaje o píldoras formativas (Crespo-Miguel & Sánchez-Saus

Laserna, 2020), vídeo póster (Kemczinski et al., 2017), vídeo digital y su

utilización en soportes y plataformas eLearning (sistemas de gestión de

aprendizajes como LMS -Learning Management System-, Mooc, Blog educativos…)

como plataformas específicas de vídeos (YouTube, Vimeo…) y repositorios en

abierto, los video tutoriales como recursos, hasta los recientes usos de las AV

(Pérez-Torregrosa et al., 2017) y las plataformas integradas en los LMS o las

específicas plataformas de AV, ocupación íntegra de nuestro trabajo.

Todos ellos son nuevas

oportunidades, técnicas y modelos para la formación de docentes que han surgido

al albor del desarrollo tecnológico en la digitalización y computación del

vídeo, pero que de algún modo sirven de soporte y recurso, y en algunos casos

algo más que esto, al definir el sentido de los modelos pedagógicos con los que

se asocian, como de las concepciones acerca de lo que se entiende que debe ser

la formación de docentes. Tal es el caso del Modelo microteaching (Sezen-Barrie

et al., 2014), el Modelo TPACK (Cabero, 2014; Leiva-Núñez et al., 2018) y otros

modelos que preconizan el análisis sobre la práctica y la interpretación de

significados a través de esta reflexión -en la acción y sobre la acción-

(Schön, 1992), reflexión crítica y la autorregulación del aprendizaje (Kim Chau

& Mei Po, 2021), el análisis del discurso narrativo (Joksimović et

al., 2018), la investigación acción (Ardley & Johnson, 2018), las redes

profesionales, y comunidades de prácticas -CoP- (Brown & Poortman, 2018) y

de indagación -CoI- (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, 2021), siendo estas dos últimas

las más generalizadas actualmente y más propias del uso de las metodologías y

plataformas tecnológicas de AV, al dotarlas de un aprendizaje más activo,

formativo, reflexivo, y con más retroalimentación sobre el recurso vídeo, tanto

entre los estudiantes del mismo grupo de clase como dotando de significados y

valores en la comunicación evaluativa entre los docentes y los estudiantes.

En términos generales, las AV

es una tecnología que permite romper la linealidad del mensaje, fragmentado en

pequeñas secuencias que pueden ser analizadas y revisadas cuantas veces

deseemos. Al tiempo que podemos anotar dentro de la misma notas con diferentes

códigos (texto, video, sonido...). Todo ello, puede estar vinculado con

etiquetas que le permiten diversas funcionalidades muy interesantes para el

estudio, análisis y enseñanza con recursos de vídeo, configurando los

principios de una Metodología de Anotaciones Multimedia -MAM- a través de

plataformas tecnológicas (Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al., 2021).

A continuación detallamos

algunas consecuencias educativas de las funcionalidades tecnológicas que

configuran cuatro principios pedagógicos básicos de MAM:

1. Fragmentación: La

anotación se realiza sobre una secuencia en el mismo vídeo, estableciendo un

vínculo directo y objetivable de cualquier comentario, interpretación o nota

sobre esa secuencia.

2. La linealidad vs.

hipermedia: Los discursos de los editores de vídeos, por su rapidez en

ocasiones o su tiempo de atención pueden atraer a una lectura más emocional que

racional, por lo que, al fragmentar se rompe la linealidad.

3. Anotaciones multimedia

como contra mensaje: La interpretación y anotación como un ejercicio de

crítica y análisis permite a los educadores y estudiantes elaborar otro

contramensaje, como una reflexión y proyección de lo que pensamos, sentimos e

interpretamos al ver el vídeo.

4. Etiquetado social y

construcción de un conocimiento compartido. La posibilidad de compartir

nuestras interpretaciones y lecturas con etiquetado social -social tagging-, dota

de unas posibilidades pedagógicas para el análisis y revisión de la lectura de

todo el grupo, como de compartir las interpretaciones y análisis en grupo y

comunidades intergeneracional como profesional.

Con el uso de MAM y eligiendo

aquellas tecnologías de anotaciones multimedia que mejor se adapten a nuestro

contexto y proyecto educativo, solo nos faltaría disponer de conocimiento sobre

los factores como las variables que más inciden en los aprendizajes desde la

literatura especializada. Por este motivo, vamos a continuación a realizar una

revisión cuyo objetivo es conocer las investigaciones sobre el impacto de las

AV en la formación de docentes inicial y permanente en todos los niveles

educativos, de tal modo que permita a investigadores y a formador de formadores

conocer las posibilidades para el diseño pedagógico de su aplicación y las

principales herramientas utilizadas para las AV.

Para lograr el objetivo de

este estudio, se concretan las siguientes preguntas de investigación a

las que se pretende dar respuesta:

- ¿Qué herramientas de

anotaciones de video han sido usadas en la formación de docentes?

- ¿Qué tipo de diseño

metodológico y variables han sido las más utilizadas en las investigaciones

seleccionadas?

- ¿Cuáles han sido las características y

número de participantes en los artículos analizados?

- ¿Cuáles han sido los

principales tópicos que se estudian en las investigaciones seleccionadas?

2. Metodología

En este estudio se ha

realizado una revisión sistemática de la literatura, como las propuestas por

Pertegal-Vega et al. (2019) o Valverde-Berrocoso et al. (2022), usadas

ampliamente con el objetivo de responder a preguntas concretas sobre una

temática de investigación. Esta revisión se ha llevado a cabo siguiendo los

estándares de calidad establecidos en la declaración PRISMA 2020 (Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses). Esta declaración

sustituye a la declaración de 2009 y aporta una nueva guía sobre los métodos

para identificar, seleccionar y evaluar con mayor fiabilidad los estudios (Page

et al., 2021). La lista de verificación consta de 27 ítems con recomendaciones

en cada uno y se incluyen los criterios de elegibilidad, fuentes de

información, estrategia de búsqueda, proceso de selección de los estudios, proceso

de extracción de los datos y lista de datos.

Estrategia de búsqueda

La búsqueda de artículos se

realizó en varias bases de datos electrónicas: Web of Science (WOS), Scopus y

ERIC. Se seleccionaron estas bases de datos por su prestigio y reputación internacional,

la representatividad de la muestra por su exigencia en los protocolos de

indexación y pueden ser complementarias, aunque existe un cierto solapamiento

en su cobertura, y los sesgos mostrados insistentemente en determinadas

disciplinas (Fernández-Batanero et al., 2020).

El enfoque principal de esta

revisión incluye las AV y la formación docente, por ello la búsqueda

bibliográfica consta de dos fases para no delimitar los resultados y garantizar

que se incluya toda la literatura relevante. En la primera fase la palabra

clave utilizada para la búsqueda en las bases de datos fue anotaciones de video

en inglés “video annotation”. En la segunda fase, se seleccionaron los estudios

sobre formación docente inicial y permanente incluidos en la selección de la

primera fase.

Criterios de selección

Para obtener una muestra de

artículos recientes que abordan específicamente las preguntas de investigación

se establecieron varios criterios de inclusión y exclusión. Los criterios de

inclusión fueron: Artículos de revistas (CI1); artículos escritos en español o

inglés (CI2) y artículos publicados entre enero de 2018 y abril de 2022 (CI3)

por la evolución y desfase de las herramientas de anotaciones de video con el

tiempo. Mientras que los criterios de exclusión fueron: Artículos duplicados

(CE1); estudios de revisión o estado del arte (CE2); uso de anotaciones de

video fuera del contexto educativo (CE3); artículos con acceso restringido o

texto completo no disponible (CE4); no se especifica la herramienta de anotaciones

de video utilizada (CE5); estudios enfocados en el desarrollo informático de la

herramienta (CE6) y uso de anotaciones de video en el contexto educativo pero

no orientadas a la formación de docentes (CE7).

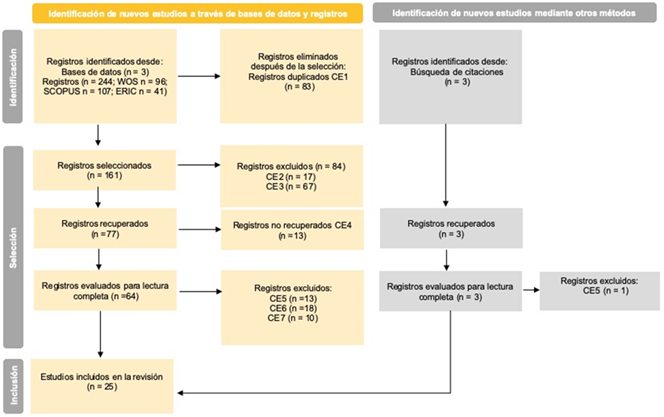

Diagrama de flujo PRISMA 2020 del proceso de selección de artículos

incluidos en la revisión

Procedimiento para seleccionar

los artículos

En la Figura 1 se presentan

las fases seguidas para identificar y seleccionar la muestra según las

recomendaciones establecidas en la declaración PRISMA (Page et al., 2021). Para

identificar los estudios se realizó una búsqueda inicial en las tres bases de

datos (WOS, Scopus y ERIC) que incluyó la palabra clave "video

annotation" y se restringió automáticamente por año, idioma y tipo de

documento siguiendo los criterios de inclusión (CI1, CI2 y CI3). En esta

búsqueda se obtuvo una muestra inicial de 244 artículos. Tras eliminar los

artículos duplicados la muestra inicial se redujo a 163 artículos. Para

seleccionar los artículos en una primera etapa se leyeron los títulos y

resúmenes y se aplicaron los criterios de exclusión (CE2 y CE3), el conjunto de

artículos se redujo a 77. Después se eliminaron los artículos con acceso

restringido (CE4) y se revisó el texto completo de los artículos para aplicar

los criterios de exclusión (CE5, CE6 y C7). Posteriormente se identificaron en

las citas de referencias 3 estudios, dos cumplían los criterios de inclusión y

se sumaron a la muestra final. La muestra definitiva está formada por 25

artículos.

3. Análisis y resultados

3.1 Análisis de los

artículos seleccionados

Primero se sintetizó la

información de los artículos en una hoja de cálculo de Google: autores, año,

preguntas y objetivos de investigación, método de investigación, participantes,

herramienta de AV, funcionalidades de la herramienta, principales resultados y

conclusiones. Posteriormente se analizó la información recogida y se clasificó

en categorías (Tabla 1) que permitieron lograr el objetivo de estudio.

Tabla 1

Datos de consumo de vídeos

|

Referencia |

Herramientas |

Método |

Participantes |

Tópicos |

|

Ardley

& Johnson (2018) |

GoReact |

Investigación acción. |

14 estudiantes y 6 tutores académicos |

Prácticum |

|

Sherry et al. (2018) |

Viddler |

Estudio

y análisis del discurso. |

12

estudiantes Formación inicial docentes de inglés |

Prácticum Análisis y reflexión sobre la

práctica. |

|

Mirriahi et al. (2018a) |

CLAS |

Diseño

experimental natural. |

111

estudiantes |

Competencias

TEFL |

|

Mirriahi et al. (2018b) |

OVAL |

Análisis

contenidos. |

163

docentes Formación Permanente Docentes Universitarios |

Análisis

y reflexión sobre la práctica. |

|

Martínez & Cebrián

(2019) |

Coannotation |

Estudios de caso Análisis de contenidos. |

27 estudiantes Formación inicial docentes de

Ciencias Sociales |

Prácticum

Análisis y reflexión sobre la práctica |

|

Boldrini et al. (2019) |

Ivideo |

Diseño

Cuasi experimental. Análisis de contenidos. |

36 docentes de Formación

Profesional |

Análisis y reflexión sobre la práctica |

|

McFadden

(2019) |

VideoAnt |

Estudios de caso |

1 docente |

Análisis y reflexión sobre la práctica |

|

Cebrián-Robles

et al. (2019) |

Coannotation |

Diseño cuasiexperimental. |

31 estudiantes Formación inicial Educación

Infantil |

Competencias

en la argumentación científica. |

|

Nilsson & Karlsson

(2019) |

YouTube |

Análisis de contenidos. |

24 estudiantes Formación inicial de docentes de

ciencias |

Prácticum. Análisis y reflexión sobre la

práctica |

|

Perini et al. (2019) |

iVideo |

Método Mixto. Diseño

Cuasiexperimental. |

197 informes de estudiantes |

Prácticum. Análisis y reflexión sobre la

práctica. |

|

Tessier & Tremion

(2020) |

Hypotheses |

Análisis contenidos en las anotaciones |

94

estudiantes de educación y 26 docentes en formación permanente. |

Competencias

en la comunicación. |

|

Ardley & Hallare (2020) |

GoReact |

Análisis

de contenidos |

32 estudiantes, 14 tutores académicos y 58 de

centro |

Prácticum |

|

Tan et al. (2020) |

360-degree video platform |

Perspectiva semiótica

social multimodal |

644 estudiantes Formación inicial de docentes en

matemáticas y ciencias |

Análisis

y reflexión sobre la práctica en videos de 360º. |

|

Mei-Po et al. (2021) |

VAT

embedded in the VBLC |

Diseño de grupos

cuasiexperimentales |

80 estudiantes Formación inicial de docentes |

Prácticum. Análisis y reflexión sobre la

práctica simulada. |

|

Ruiz-Rey et al. (2021a) |

Coannotation |

Método mixto. Encuesta de satisfacción |

132 estudiantes Formación inicial de docente |

Videoguías y sus anotaciones como recursos

didácticos |

|

Zaier et al. (2021) |

Blackboard Teachscape |

Método mixto. Análisis de contenidos |

25 estudiantes Formación inicial de docentes en

Matemáticas, Ciencia, Educación Física e Historia |

Prácticum. |

|

Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al. (2021) |

Coannotation |

Métodos mixtos. Diseño cuasiexperimental.

Análisis de contenidos |

274 estudiantes Formación inicial de docentes |

Competencias en evaluación de proyectos de

innovación educativa. |

|

Mirriahi (2021) |

OVAL |

Diseño experimental |

93 estudiantes y personal de la Universidad |

Impacto del diseño con anotaciones de video en el aprendizaje |

|

Kennedy-KAM (2021) |

VideoVox |

Análisis de contenidos |

14 estudiantes. Formación inicial de docents de

ciencias |

Competencias científicas |

|

Kim

Chau Leung & Mei Po Shek (2021) |

VBLC |

Análisis

de contenido en los diarios de autorreflexión |

73 estudiantes |

Prácticum. Análisis y reflexión sobre la

práctica |

|

Ruiz-Rey et al. (2021b) |

Coannotation |

Método Mixto Análisis de contenidos y etiquetas

sociales |

41 docentes universitarios |

Prácticum. Análisis y reflexión sobre la

práctica |

|

Suh et al. (2021) |

GoReact |

Análisis de contenidos de las anotaciones en los

vídeos |

32 docentes Formación permanente docentes de

matemáticas |

Análisis y reflexión sobre la práctica. Lesson Study |

|

Blau & Shamir-Inbal

(2021) |

Annoto |

Método Mixto Modelo CoI: presencia cognitiva,

educativa y social. |

880 estudiantes |

Analítica del aprendizaje con el análisis de

contenido basado en el modelo CoI |

|

Craig (2021) |

YouTube |

Análisis de contenidos, Diseño de grupos. Análisis semiótico. |

141

estudiantes Formación inicial de docentes |

Interactividad y alfabetización en Sistemas de

Video. |

|

Day et al. (2022) |

Pitch2Pee |

Análisis

de contenidos sobre las anotaciones y puntuaciones de la rúbrica de

evaluación. |

56

estudiantes de formación inicial de docentes |

Presentación

de proyectos en vídeo con evaluación y retroalimentación de pares en línea. |

3.2 Resultados

De todos los artículos

seleccionados que podemos ver en la Tabla 1, hemos categorizado según los siguientes

elementos: a. las herramientas empleadas, b. los métodos y variables

utilizadas, c. el tipo y número de participantes, y por último, d. el tópico

que se estudia en dichos artículos. Veamos a continuación cada apartado por

separado:

a.

En cuanto a las herramientas

de AV empleadas en los estudios analizados encontramos diversidad de soluciones

técnicas, que van: desde la posibilidad de integrarse en la propia plataforma

institucional a una plataforma específica de AV con otras funciones propias de

las plataformas LMS (evaluación, lista de preguntas, foros, etc.). Encontramos

en la mayoría de las plataformas de AV funciones similares que permiten

aplicaciones a proyectos distintos, como: etiquetado, anotaciones, anotaciones

multimedia, réplicas a las anotaciones, exportación de datos y conversaciones

generadas, selección de secuencias en el vídeo, anotaciones dentro o fuera del

vídeo, etc.

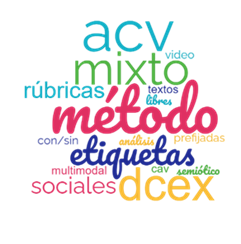

b.

Sobre los métodos de

investigación empleados encontramos en los trabajos principalmente métodos

mixtos (ver nube de palabras en la Figura 2) con diseños cuasi experimentales y

en menor medida experiencias de evaluación y programas de colaboración entre

docentes con metodologías de evaluación formativa, estudios de casos e

investigación acción. Entre las técnicas de recogida y tratamiento de datos

encontramos el análisis de contenidos mediante categorías y etiquetado social,

seguido de encuestas de opinión y entrevistas en menor medida.

Nube de palabras con los métodos empleados recogidos en la Tabla 1.

Elaborada con Nubedepalabras.com

En el diseño cuasiexperimental

se comparan grupos a los que se aplican diferentes variables de estudio como

podrían ser: con y sin etiquetas, etiquetas prefijadas o libres

(Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al., 2021), diseño de tareas con anotaciones vs.

preguntas (Mirriahi, 2021), percepción en el uso de la metodología (Ardley

& Johnson 2018), con y sin ninguna etiqueta que oriente el análisis como

también anotaciones en mensajes de texto vs. vídeo (Cebrián-Robles et al.,

2019), las tres variables del modelo Comunidades de Indagación -CoI- “presencia

cognitiva, didáctica y social” (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, 2021), el

comportamiento de los estudiantes con y sin metodologías de AV (Tan et al.

2020; Mei-Po et al., 2021), y el análisis de contenidos según la

retroalimentación recíproca entre docentes en activo (Mirriahi et al., 2018;

Boldrini et al., 2019), las reflexiones y análisis de experiencias en el

practicum y prácticas externas en formación inicial (Martínez-Romera &

Cebrián-Robles, 2019; Nilsson & Karlsson, 2019; Ardley & Hallare, 2020)

y las anotaciones en la evaluación de pares y autoevaluación (Zaier et al.,

2021; Day et al., 2022).

c.

En cuanto a los participantes

del estudio predominantemente son estudiantes en formación inicial, seguido de

docentes en formación permanente, tutores académicos y profesionales. Siendo el

tamaño de los grupos muy diferentes y su tamaño dependiendo del tipo de diseño

de investigación, como: pequeños grupos de estudiantes, docentes y tutores

(entre 5 a 15), grupos medianos de estudiantes

y docentes en formación permanente entre 50 y 100, y grupos más

numerosos de 100 a 600 estudiantes de formación inicial.

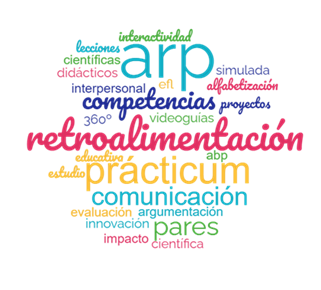

d.

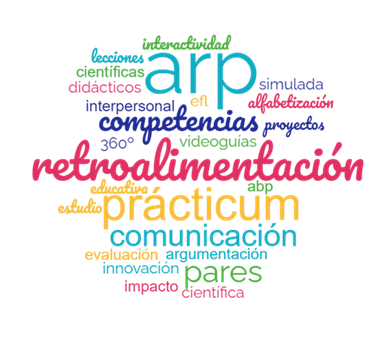

Según los tópicos encontrados

en nuestro estudio existe una mayoría de temas (15 de los 25 encontrados), como

podemos ver en la nube de palabras en la Figura 3, que abordan el estudio

relativo al “Análisis y reflexión sobre la práctica -ARP-” dentro de la materia

del Prácticum y las prácticas externas, como una importante conexión entre el

mundo laboral en los centros de prácticas y la formación teórica en la

facultad, y un importante método y tecnología para la reflexión del estudiante

y los docentes sobre la práctica (Perini et al., 2019). Además de este tópico

hallamos otros como: la retroalimentación y comunicación entre estudiantes y

entre docentes, la formación en competencias y argumentación científica, la

alfabetización y competencias digitales, la utilidad y satisfacción en el uso de

las AV para el aprendizaje, la funcionalidad técnica de las herramientas, el

impacto sobre el aprendizaje, la comprensión de contenidos, la capacidad de

autorregulación del aprendizaje, la capacidad reflexiva y la competencia

comunicativa (Kim Chau & Mei Po, 2021), la escritura académica, la

conversación académica vs. social, las Video Guías (Ruiz-Rey, 2021b), la

alfabetización participativa (Craig, 2021), y el conocimiento situado y

profesional de los docentes (Kennedy-Kam, 2021).

Nube de palabras de los tópicos de los artículos analizados de cada uno

de los artículos revisados recogidos en la Tabla 1. Elaborada con

Nubedepalabras.com

4. Conclusiones

Los vídeos digitales se han

convertido en una tecnología y un recurso esencial en la educación superior,

con un aumento considerable en la investigación sobre el tema, que para Poquet

et al. (2018) aún carece de una visión general de su impacto en la enseñanza y

aprendizaje universitario. Creemos que la velocidad y los tiempos que requiere

la investigación, experimentación y evaluación en educación no va al mismo

ritmo que el desarrollo de tecnologías emergentes; por lo que, al terminar una

revisión literaria encontramos nuevas tecnologías y experiencias con resultados

donde no hubo tiempo de evaluar. Algo similar ha sucedido con el caso de la

evolución de las tecnologías de AV, que han tenido un aumento significativo en

la formación de docentes muy recientemente entre los cinco y diez últimos años,

aplicándose a diferentes contextos y situaciones educativas; especialmente en

la situación de pandemia con la Covid19, pero que aún necesita de más

investigaciones.

Las anotaciones de vídeo

permiten a los participantes anotar y compartir las interpretaciones, preguntas

o reflexiones que los contenidos del vídeo muestran. Según los estudios y

revisiones previas, como los trabajos de Koedinger et al. (2020) cuando evaluó

el aprendizaje producido en un Mooc con 27.720 estudiantes. El verdadero

impacto del uso del vídeo es cuando van más allá de solo ver vídeo, y se

diseñan tareas y actividades que favorezcan la motivación y compromiso de los

estudiantes con los ejercicios. Igualmente, el diseño de estas actividades

sugiere, según los trabajos de Mirriahi et al. (2021), que se utilicen las AV

cuando haya conocimientos previos sobre el tema, mientras que el diseño con

preguntas y retroalimentación inmediata se intercalan en los vídeos cuando los

estudiantes no tengan conocimientos previos. Todo ello nos lleva a pensar que

el gran efecto radica en las muchas posibilidades y diseños diferentes de

tareas, ejercicios, comunidades de aprendizaje, etc., que permiten la

metodología de AV.

Estas posibilidades de anotar

digitalmente mediante etiquetas, si se quiere, de forma privada o colectiva,

produce grandes bases de datos para la investigación sobre los comportamientos

en internet, que se une al auge de las prácticas en redes sociales y

comunidades de prácticas como modelos muy significativos para la formación en

competencias docentes; por lo que, no deberíamos olvidar las ventajas que permiten

las plataformas de anotaciones para soportar estos modelos y comunidades de

indagación (Blau, & Shamir-Inbal, 2021), modelos de comunidades de

prácticas (Brown & Poortman, 2018) y redes de aprendizaje colectivo para el

desarrollo profesional (Ruiz-Rey, 2021b). Esta metodología facilita el análisis

de los discursos teóricos, de las narrativas compartidas que se discuten sobre

las experiencias vividas, y puede surgir un aprendizaje colectivo que

proporcione la discusión en comunidades de prácticas educativas, como

competencias necesarias en la formación inicial de docentes para crear redes

profesionales en el futuro.

En nuestro estudio hemos

realizado una revisión sistemática sobre el uso específico de las AV en la

formación de docentes (inicial y permanente), coincidente en parte sus

resultados con otras revisiones más genéricas de la literatura en el uso de AV

en educación (Rich & Hannafin, 2009; Pérez-Torregrosa et al., 2017;

Evi-Colombo & Cattaneo, 2020; Chui-Lami & Habil, 2021), donde se

concluye la utilidad de las AV para la formación de docentes, así como el apoyo

inestimable para que los tutores universitarios supervisen a los estudiantes en

las prácticas e interactúen con los tutores profesionales en los centros

escolares (Ardley & Johnson, 2018). En los artículos seleccionados

encontramos objetivos y variables de estudios, tales como: la satisfacción, la

cantidad y calidad de la reflexión sobre la práctica, la comprensión conceptual

de los contenidos, la autorregulación, la comunicación y la retroalimentación.

Siendo el análisis de las experiencias prácticas y el prácticum el uso más

frecuente de las AV en las referencias seleccionadas.

Las herramientas encontradas

en la presente revisión no agotan todas las que existen en internet. No

obstante, y según el presente estudio, todas las plataformas disponen de

funciones para anotar dentro o fuera del vídeo, y no todas pueden realizar

hipervínculos añadiendo otros vídeos o enlaces, encontrando un gran número de

las mismas con funciones similares que manifiestan una tendencia a la

socialización de los aprendizajes mediante etiquetas o social tagging. También

podemos añadir la capacidad de poder exponer los resultados de las respuestas

de los estudiantes inmediatamente de forma que facilita la interacción y

dinámicas más activas en el grupo de clase. A pesar de la limitación en el

presente trabajo y no siendo el objetivo de este estudio, hemos realizado un

análisis en profundidad suficiente sobre las funcionalidades de las

herramientas, para argumentar lo dicho anteriormente y afirmar que en la Tabla

1 están las herramientas que más se utilizan actualmente en formación inicial y

permanente de docentes; si bien, pensamos que es necesario un estudio más

amplio en el futuro que analice con más detalle las funciones que cada una de

estas herramientas permiten, dando una necesaria comparativa que facilite la

elección de herramientas según cada proyecto.

El desarrollo de tecnologías

emergentes (la inteligencia artificial, el big-data, la gamificación en

entornos de “Metaverso” con el uso de la realidad virtual y aumentada…) que aún

están en sus primeras aplicaciones educativas, son el indicio de nuevas

implicaciones para que el vídeo digital se convierta en “realidades paralelas”,

con innovadoras funcionalidades de las anotaciones multimedia en el

“Metaverso”, que nos solicitará de nuevas revisiones de su literatura una vez

aumenten las investigaciones emprendidas recientemente, como las iniciativas

por Mei-Po et al. (2021) para crear realidades simuladas y juegos de rol para

la educación, y que unido al auge de los sistemas de videoconferencia en la

enseñanza universitaria tras la Covid19, prometen un salto innovador, como

nuevos escenarios y ambientes educativos.

5. Financiación

Grupo

de investigación Gtea SEJ-462, Junta de Andalucía, gteavirtual.org

Literature

review on video annotations in teacher education

1.

Introduction

The trend in the use of video formats at all educational

levels was a booming topic before the covid19, and with this pandemic has seen

an exponential increase in its production with the use of videoconferencing

systems in a rapid transition to distance education. The use of

videoconferencing during the pandemic by teachers and students was highly

successful, as education did not come to a standstill as a result. However,

sometimes this use turned into abuse, as we found ourselves so many hours

concentrated and mediated by a screen. For this reason, and after this

experience with a double result, both request a more dynamic and active

methodology in the use of videoconferencing, such as the use of videos as

resources with higher quality, interactivity and motivation for teaching than

those produced by this exceptionality experienced by all.

Video as a resource and technology had been applying

in all areas, being in university education and in the training of degrees in

education a highly developed topic (Bayram, 2012; Arya et al., 2014; Nielsen,

2015; Gallego-Arrufat, 2015; Chui-Lami & Habil, 2021). Where we find many

examples in the use of videos in the initial as well as ongoing training of

teachers in the different subjects such as mathematics teaching (Barth-Cohen,

2018), science teaching (Luna & Sherin, 2017), tutorials and external

practices in the University-Practice Center (Youens et al., 2014), such as

professional identity under video autobiographies (Ó Gallchóir et al., 2018),

among others. Being quite new the use of video annotations (hereinafter, VA)

within lifelong learning and through the creation of professional communities

and networks (Ruiz-Rey et al., 2021a).

In an attempt to break the linearity of the video

sequence and provide it with more interactivity, multimedia annotation

technologies are providing a better and easy use of videos in teaching at all

levels, especially in those that have been experienced the most as it is in

higher education (Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al., 2015; Cebrián-Robles et al.,

2016; Po-Sheng et al., 2018; Marçal et al., 2020; Hefter & Berthold, 2020;

Ruiz-Rey et al., 2021b; Mei-Po et al., 2021), where in teacher training is

taking up a more innovative, flexible and creative approach that saves the

criticism found in the microteaching approaches of the past, in that, it is

offered as a resource and tool in the hands of the teachers themselves for

initial and ongoing training and the modality they decide. Within the first,

initial training we have an interesting review on video annotations in

Pérez-Torregrosa et al. (2017). We will now present a technological and

methodological development of multimedia annotations in general and video in

particular.

Video annotations (VA) in teacher training

Video as a support and resource in teacher training

has an important numerical magnitude and versatility of uses in the specialized

literature, which has evolved in parallel to the digital transformation, moving

from the first magnetic tapes to digital video, with a diversity of practices

and pedagogical models that facilitated the coining of a profusion of terms of

its own. Examples of this prodigality are the following denominations: learning

pills or formative pills (Crespo-Miguel & Sánchez-Saus Laserna, 2020),

video poster (Kemczinski et al., 2017), digital video and its use in eLearning

supports and platforms (learning management systems such as LMS -Learning

Management System-, Mooc, educational Blog...) as specific video platforms

(YouTube, Vimeo...) and open repositories, video tutorials as resources, until

the recent uses of VAs (Pérez-Torregrosa et al., 2017) and platforms integrated

in LMS or specific VA platforms, full occupation of our work.

All of them are new opportunities, techniques and

models for teacher training that have emerged at the dawn of technological

development in video digitization and computing, but that somehow serve as a

support and resource, and in some cases something more than this, by defining

the meaning of the pedagogical models with which they are associated, as of the

conceptions about what it is understood that teacher training should be. Such

is the case of the Microteaching Model (Sezen-Barrie et al., 2014), the TPACK

Model (Cabero, 2014; Leiva-Núñez et al., 2018) and other models that advocate

the analysis on practice and the interpretation of meanings through this

reflection -in action and on action- (Schön, 1992), critical reflection and

self-regulation of learning (Kim Chau & Mei Po, 2021), narrative discourse

analysis (Joksimović et al., 2018), action research (Ardley & Johnson

2018), professional networks, and communities of practice -CoP- (Brown &

Poortman, 2018) and communities of inquiry -CoI- (Blau & Shamir-Inbal,

2021), the latter two being the most widespread nowadays and more typical of

the use of VA methodologies and technological platforms, by providing them with

a more active, formative, reflective learning, and with more feedback on the

video resource, both among students in the same class group and by providing

meanings and values in the evaluative communication between teachers and

students.

In general terms, VA is a technology that allows us to

break the linearity of the message, fragmented in small sequences that can be

analyzed and reviewed as many times as we wish. At the same time we can

annotate within the same notes with different codes (text, video, sound...).

All of this can be linked to tags that allow various very interesting

functionalities for the study, analysis and teaching with video resources,

configuring the principles of a Multimedia Annotation Methodology -MAM- through

technological platforms (Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al., 2021)

The following are some of the educational consequences

of the technological functionalities that make up the four basic pedagogical

principles of MAM:

1. Fragmentation: The annotation is made on a

sequence in the same video, establishing a direct and objectifiable link of any

commentary, interpretation or note on that sequence.

2. Linearity vs. hypermedia: The speeches of

video editors, because of their speed sometimes or their attention span can

attract a more emotional than rational reading, so, fragmenting breaks the

linearity.

3. Multimedia annotations as a counter-message:

Interpretation and annotation as an exercise of criticism and analysis allows

educators and students to elaborate another counter-message, as a reflection

and projection of what we think, feel and interpret when watching the video.

4. Social labeling and construction of shared

knowledge. The possibility of sharing our interpretations and readings with

social tagging provides pedagogical possibilities for the analysis and revision

of the reading of the whole group, as well as sharing interpretations and

analysis in group and intergenerational communities as professionals.

With the use of MAM and choosing those multimedia

annotation technologies that best suit our context and educational project, we

would only need to have knowledge about the factors and variables that have the

greatest impact on learning from the specialized literature. For this reason,

we will now carry out a review whose objective is to know the research on the

impact of VA in initial and permanent teacher training at all educational

levels, so that researchers and trainers of trainers can know the possibilities

for the pedagogical design of its application and the main tools used for VA.

In order to achieve the objective of this study, the

following research questions are specified and are intended to be answered:

- What video annotation

tools have been used in teacher education?

- What type of

methodological design and variables have been the most used in the selected

research?

- What have been the

characteristics and number of participants in the analyzed articles?

- What have been the

main topics studied in the selected research?

2. Methodology

In this study, a systematic review of the literature,

such as those proposed by Pertegal-Vega et al. (2019) or Valverde-Berrocoso et

al. (2022), widely used with the aim of answering specific questions on a

research topic, was performed. This review has been carried out following the

quality standards established in the PRISMA 2020 statement (Preferred Reporting

Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses). This statement replaces the

2009 statement and provides new guidance on methods for more reliably

identifying, selecting and assessing studies (Page et al., 2021). The checklist

consists of 27 items with recommendations in each item and includes eligibility

criteria, information sources, search strategy, study selection process, data extraction

process and data list.

Search strategy

The search for articles was carried out in several

electronic databases: Web of Science (WOS), Scopus and ERIC. These databases were

selected because of their prestige and international reputation, the

representativeness of the sample due to their demanding indexing protocols and

they may be complementary, although there is some overlap in their coverage,

and the biases insistently shown in certain disciplines (Fernández-Batanero et

al., 2020).

The main focus of this review includes VA and teacher

education, therefore the literature search consists of two phases so as not to

delimit the results and to ensure that all relevant literature is included. In

the first phase, the keyword used for the database search was video annotation.

In the second phase, the studies on initial and continuing teacher training

included in the selection of the first phase were selected.

Selection criteria

To obtain a sample of recent articles specifically

addressing the research questions, several inclusion and exclusion criteria

were established. The inclusion criteria were: journal articles (IC1); articles

written in Spanish or English (IC2) and articles published between January 2018

and April 2022 (IC3) due to the evolution and lag of video annotation tools

over time. While the exclusion criteria were: duplicate articles (EC1); review

or state of the art studies (EC2); use of video annotations outside the

educational context (EC3); articles with restricted access or full text not

available (EC4); video annotation tool used not specified (EC5); studies

focused on the informatics development of the tool (CE6) and use of video

annotations in the educational context but not oriented to teacher training

(EC7).

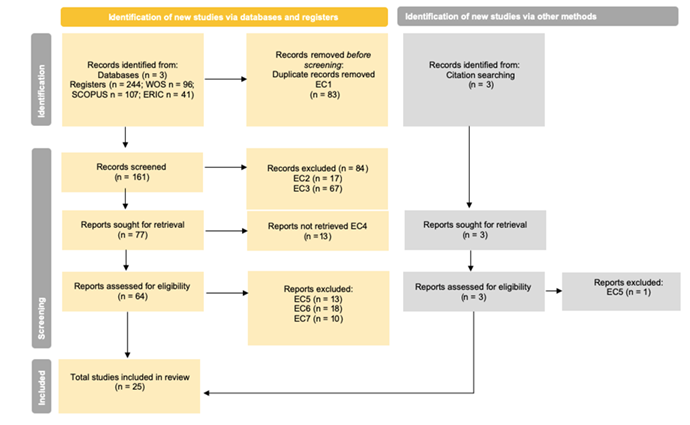

Procedure for selecting the articles

In Figure 1 shows the phases followed to identify and

select the sample according to the recommendations established in the PRISMA

statement (Page et al., 2021). To identify the studies, an initial search was

performed in the three databases (WOS, Scopus and ERIC) that included the

keyword "video annotation" and was automatically restricted by year,

language and type of document following the inclusion criteria (IC1, IC2 and

IC3). This search yielded an initial sample of 244 articles. After eliminating

duplicate articles the initial sample was reduced to 163 articles. To select

the articles in a first stage, the titles and abstracts were read and the

exclusion criteria were applied (EC2 and EC3), the set of articles was reduced

to 77. Then the articles with restricted access (EC4) were eliminated and the

full text of the articles was reviewed to apply the exclusion criteria (EC5,

EC6 and EC7). Subsequently, 3 studies were identified in the reference

citations, 2 met the inclusion criteria and were added to the final sample. The

final sample consists of 25 articles.

PRISMA 2020 flow

chart of the selection process of articles included in the review

3. Analysis and results

3.1 Analysis of selected articles

First, the information from the articles was

synthesized in a Google spreadsheet: authors, year, research questions and

objectives, research method, participants, VA tool, functionalities of the

tool, main results and conclusions. Subsequently, the information collected was

analyzed and classified into categories (Table 1) that allowed the study

objective to be achieved.

3.2. Results

Of all the selected articles shown in Table 1, we have

categorized them according to the following elements: a. the tools used, b. the

methods and variables used, c. the type and number of participants, and

finally, d. the topic studied in these articles. Each section is discussed

separately below:

a.

Regarding the VA tools used in

the studies analyzed, we found a variety of technical solutions, ranging from

the possibility of integrating into the institutional platform itself to a

specific VA platform with other functions typical of LMS platforms (evaluation,

list of questions, forums, etc.). We found in most of the VA platforms similar

functions that allow applications to different projects, such as: tagging,

annotations, multimedia annotations, replication of annotations, export of data

and generated conversations, selection of sequences in the video, annotations

inside or outside the video, etc.

Table 1

Selected and sorted references by tool categories, method, participants

and topics

|

Reference |

Tools |

Method |

Participant |

Topics |

|

Ardley

& Johnson (2018) |

GoReact |

Action research. |

14 Students and 6 academic

tutors. |

Practicum. |

|

Sherry et al. (2018) |

Viddler |

Study

and analysis of discourse. |

12 Students Initial English

teacher training. |

Practicum Analysis and

reflection on practice. |

|

Mirriahi et al. (2018a) |

CLAS |

Natural

experimental design. |

111

Students. |

TEFL

competencies. |

|

Mirriahi et al. (2018b) |

OVAL |

Content analysis. |

163

Teachers Continuing Education University Teachers. |

Analysis

and reflection on practice. |

|

Martínez & Cebrián

(2019) |

Coannotation |

Case studies Content Analysis. |

27 Students Initial Social

Science Teacher Training. |

Practicum Analysis and

reflection on practice. |

|

Boldrini et al. (2019) |

Ivideo |

Quasi-experimental design. Content analysis. |

36 Vocational Training

Teachers. |

Analysis and reflection on

practice. |

|

McFadden

(2019) |

VideoAnt |

Case studies. |

1 Teacher. |

Analysis and reflection on

practice. |

|

Cebrián-Robles

et al. (2019) |

Coannotation |

Quasi-experimental design. |

31 students Initial

training Early Childhood Education. |

Competencies in scientific argumentation. |

|

Nilsson & Karlsson

(2019) |

YouTube |

Content analysis. |

24 Students Initial science

teacher training. |

Practicum. Analysis and

reflection on practice. |

|

Perini et al. (2019) |

iVideo |

Mixed Method.

Quasi-experimental design. |

197 Student reports. |

Practicum. Analysis and

reflection on practice. |

|

Tessier & Tremion

(2020) |

Hypotheses |

Analysis contained in the

annotations. |

94 Education students and

26 teachers in continuing education. |

Communication skills. |

|

Ardley & Hallare (2020) |

GoReact |

Content analysis. |

32 Students, 14 Academic

Tutors and 58 Center Tutors. |

Practicum. |

|

Tan et al. (2020) |

360-degree video platform |

Multimodal social semiotic

perspective. |

644 Students Initial

teacher training in mathematics and science. |

Analysis and reflection on

the practice in 360º videos. |

|

Mei-Po et al. (2021) |

VAT

embedded in the VBLC |

Quasi-experimental group

design. |

80 Students Initial teacher training. |

Practicum. Analysis and

reflection on the simulated practice. |

|

Ruiz-Rey et al. (2021a) |

Coannotation |

Mixed method. Satisfaction survey. |

132 Students Initial teacher training. |

Videoguides and their

annotations as teaching resources. |

|

Zaier et al. (2021) |

Blackboard Teachscape |

Mixed method. Content analysis. |

25 Students Initial teacher

training in Mathematics, Science, Physical Education and History. |

Practicum. |

|

Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al. (2021) |

Coannotation |

Mixed methods.

Quasi-experimental design. Content

analysis. |

274 Students Initial teacher training. |

Competencies in evaluation

of educational innovation projects. |

|

Mirriahi (2021) |

OVAL |

Experimental design. |

93 Students and University staff. |

Impact of video-annotated

design on learning. |

|

Kennedy-KAM (2021) |

VideoVox |

Content analysis. |

14 Students. Initial

training of science teachers. |

Scientific competencies. |

|

Kim

Chau Leung & Mei Po Shek (2021) |

VBLC |

Content analysis in

self-reflection diaries. |

73 Students. |

Practicum. Analysis and

reflection on practice. |

|

Ruiz-Rey et al. (2021b) |

Coannotation |

Mixed Method Content

analysis and social tags. |

41 University professors. |

Practicum. Analysis and

reflection on practice. |

|

Suh et al. (2021) |

GoReact |

Content analysis of video

annotations. |

32 Teachers Continuing

education for mathematics teachers. |

Analysis and reflection on

practice. Lesson

Study. |

|

Blau & Shamir-Inbal

(2021) |

Annoto |

Mixed Method CoIaboration

Model: cognitive, educational and social presence. |

880 Students. |

Learning analytics with

content analysis based on the CoIaboration Model. |

|

Craig (2021) |

YouTube |

Content analysis, Group

design. Semiotic analysis. |

141 Students Initial teacher training. |

Interactivity and Literacy

in Video Systems. |

|

Day et al. (2022) |

Pitch2Pee |

Content

analysis on the evaluation rubric annotations and scores. |

56 Initial teacher education students. |

Video presentation of

projects with online peer review and feedback. |

b.

Regarding the research methods

used in the studies, we found mainly mixed methods (see word cloud in Figure 2)

with quasi-experimental designs and, to a lesser extent, evaluation experiences

and collaborative programs among teachers with formative evaluation

methodologies, case studies and action research. Among the data collection and

processing techniques we found content analysis using categories and social

labeling, followed by opinion surveys and interviews to a lesser extent.

Word cloud with the methods used in Table 1.

Elaborated with Nubedepalabras.com.

In the quasi-experimental

design, groups are compared to which different study variables are applied such

as: with and without labels, prefixed or free labels (Cebrián-de-la-Serna et al.,

2021), task design with annotations vs. questions (Mirriahi, 2021), perception

in the use of the methodology (Ardley & Johnson 2018), with and without any

label to guide the analysis as well as annotations in text messages vs. video

(Cebrián-Robles et al., 2019), the three variables of the Communities of

Inquiry -CoI- model "cognitive, didactic and social presence" (Blau

& Shamir-Inbal, 2021), students' behavior with and without VA methodologies

(Tan et al. 2020; Mei-Po et al., 2021), and content analysis according to

reciprocal feedback between practicing teachers (Mirriahi et al., 2018 Boldrini

et al., 2019), reflections and analysis of practicum and externship experiences

in initial training (Martínez-Romera & Cebrián-Robles, 2019; Nilsson &

Karlsson, 2019; Ardley & Hallare, 2020), and annotations in peer and

self-assessment (Zaier et al., 2021; Day et al., 2022).

c.

As for the participants of the

study, they are predominantly students in initial training, followed by

teachers in continuing education, academic tutors and professionals. The size

of the groups is very different and their size depends on the type of research

design, such as: small groups of students, teachers and tutors (between 5 to

15), medium-sized groups of students and teachers in continuing education

between 50 and 100, and larger groups of 100 to 600 students in initial

training.

d.

According to the topics found

in our study there is a majority of topics (15 of the 25 found), as we can see

in the word cloud in Figure 3, that address the study related to the

"Analysis and reflection on practice -ARP-" within the subject of the

Practicum and external practices, as an important connection between the

working world in the practice centers and the theoretical training in the

faculty, and an important method and technology for student and teachers

reflection on practice (Perini et al., 2019). In addition to this topic we

found others such as: feedback and communication among students and among

teachers, training in scientific competences and argumentation, digital

literacy and competences, usefulness and satisfaction in the use of VAs for

learning, technical functionality of the tools, impact on learning, content

comprehension, learning self-regulation capacity, reflective capacity and

communicative competence (Kim Chau & Mei Po, 2021), academic writing,

academic vs. social, Video Guides (Ruiz-Rey, 2021b), participatory literacy

(Craig, 2021), and teachers' situated and professional knowledge (Kennedy-Kam,

2021).

Figure 3

Word cloud of the

topics of the articles analyzed for each of the articles reviewed in Table 1.

Elaborated with Nubedepalabras.com.

4. Conclusions

Digital videos have become an essential technology and

resource in higher education, with a considerable increase in research on the

topic, which for Poquet et al. (2018) still lacks an overview of its impact on

university teaching and learning. We believe that the speed and times required

for research, experimentation and evaluation in education does not keep pace

with the development of emerging technologies; therefore, at the end of a

literature review we find new technologies and experiences with results where

there was no time to evaluate. Something similar has happened with the case of

the evolution of VA technologies, which have had a significant increase in

teacher training very recently between the last five and ten years, being

applied to different educational contexts and situations; especially in the

pandemic situation with Covid19, but which still needs more research.

Video annotations allow participants to annotate and

share interpretations, questions or reflections that the video contents show.

According to previous studies and reviews, such as the work of Koedinger et al.

(2020) when they evaluated the learning produced in a Mooc with 27,720

students. The real impact of video use is when they go beyond just watching

video, and tasks and activities are designed to encourage student motivation

and engagement with the exercises. Likewise, the design of these activities

suggests, according to the work of Mirriahi et al. (2021), that VAs are used when

there is prior knowledge about the topic, while the design with questions and

immediate feedback are interspersed in the videos when students have no prior

knowledge. All this leads us to think that the great effect lies in the many

different possibilities and designs of tasks, exercises, learning communities,

etc., that the VA methodology allows.

These possibilities of digitally annotating through

tags, if desired, privately or collectively, produce large databases for

research on internet behaviors, which joins the rise of social networking

practices and communities of practice as very significant models for training

in teaching competencies; so, we should not forget the advantages that

annotation platforms allow to support these models and communities of inquiry

(Blau, & Shamir-Inbal, 2021), communities of practice models (Brown &

Poortman, 2018) and collective learning networks for professional development

(Ruiz-Rey, 2021b). This methodology facilitates the analysis of theoretical

discourses, shared narratives that discuss lived experiences, and collective

learning can emerge that provides discussion in communities of educational

practice, as competencies needed in initial teacher education to create

professional networks in the future.

In our study we have conducted a systematic review on

the specific use of TAs in teacher education (initial and continuing),

partially coinciding its results with other more generic reviews of the

literature on the use of TAs in education (Rich & Hannafin, 2009; Pérez-Torregrosa

et al., 2017; Evi-Colombo & Cattaneo, 2020; Chui-Lami & Habil, 2021),

where the usefulness of TAs for teacher education is concluded, as well as the

invaluable support for university tutors to supervise students in internships

and interact with professional tutors in schools (Ardley & Johnson, 2018).

In the selected articles we found study objectives and variables, such as:

satisfaction, quantity and quality of reflection on practice, conceptual

understanding of content, self-regulation, communication, and feedback. Being

the analysis of practical experiences and practicum the most frequent use of

TAs in the selected references.

The tools found in this review do not exhaust all

those that exist on the Internet. However, and according to the present study,

all the platforms have functions for annotating inside or outside the video,

and not all of them can make hyperlinks by adding other videos or links,

finding a large number of them with similar functions that show a tendency to

socialize learning by means of labels or social tagging. We can also add the

ability to display the results of the students' answers immediately in a way

that facilitates interaction and more active dynamics in the class group.

Despite the limitation in the present work and not being the objective of this

study, we have carried out a sufficient in-depth analysis of the

functionalities of the tools to argue what was said above and affirm that in

Table 1 are the tools that are currently most used in initial and continuing

teacher training; although we think that a broader study is needed in the

future to analyze in more detail the functions that each of these tools allow,

giving a necessary comparison to facilitate the choice of tools according to

each project.

The development of emerging technologies (artificial

intelligence, big-data, gamification in "Metaverse" environments with

the use of virtual and augmented reality...) that are still in their first

educational applications, are the indication of new implications for digital

video to become "parallel realities", with innovative functionalities

of multimedia annotations in the "Metaverse", that will ask us for

new literature reviews once the recently undertaken researches increase, such

as the initiatives by Mei-Po et al. (2021) to create simulated realities and

role-playing games for education, and which together with the rise of

videoconferencing systems in university education after Covid19 , promise an

innovative leap, as new scenarios and educational environments.

5. Financing

Grupo de investigación Gtea

SEJ-462, Junta de Andalucía, gteavirtual.org

References

Ardley, J., & Johnson, J. (2018). Video Annotation Software in Teacher Education: Researching University Supervisor’s Perspective of a 21st-Century Technology. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 47(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239518812715

Ardley, J., & Hallare, M. (2020). The Feedback

Cycle: Lessons Learned With Video Annotation Software During Student Teaching. Journal

of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 94-112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520912343

Arya, P., Christ, T., & Chiu, M. M. (2014).

Facilitation and Teacher Behaviors: An Analysis of Literacy Teachers’

Video-Case Discussions. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487113511644

Barth-Cohen, L. A., Little, A. J., & Abrahamson,

D. (2018). Building Reflective Practices in a Pre-service Math and Science

Teacher Education Course That Focuses on Qualitative Video Analysis. Journal

of Science Teacher Education, 29(2), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2018.1423837

Bayram, L. (2012). Use of Online Video Cases in

Teacher Training. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47,

1007–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.770

Blau, I., & Shamir-Inbal, T. (2021). Writing

private and shared annotations and lurking in Annoto hyper-video in academia:

Insights from learning analytics, content analysis, and interviews with

lecturers and students. Educational Technology Research and Development: ETR

& D, 69(2), 763–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09984-5

Boldrini, E., Cattaneo, A.,

& Evi-Colombo, A. (2019). Was it worth the effort? An exploratory study on the

usefulness and acceptance of video annotation for in-service teachers training

in VET sector. Research on Education and Media, 11(1), 100–108. https://doi.org/10.2478/rem-2019-0014

Brown, Ch. & Poortman C. L., (Eds.), (2018).

Networks for Learning: Effective Collaboration for Teacher, School and System

Improvement. Routledge.

Cabero, J. (dir.) (2014). La

formación del profesorado en TIC: Modelo TPACK (Conocimiento Tecnológico,

Pedagógico y de Contenido). Secretariado de Recursos Audiovisuales y Nuevas

Tecnologías de la Universidad de Sevilla

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M.,

Bartolomé-Pina, A., Cebrián-Robles, D., & Ruiz-Torres, M. (2015). Estudio

de los Portafolios en el Prácticum: Análisis de un PLE-Portafolios. Relieve,

21(2), 1–18. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7203/relieve.21.2.7479

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M.,

Gallego-Arrufat, M. J., & Cebrián-Robles, V. (2021). Multimedia

Annotations for Practical Collaborative Reasoning. Journal of New Approaches

in Educational Research, 10(2), 264–278. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2021.7.664

Cebrián-Robles, D.,

Blanco-López, Á., & Noguera-Valdemar, J. (2016). El uso de anotaciones

sobre vídeos en abierto como herramienta para analizar las concepciones de los

estudiantes de pedagogía sobre un problema ambiental. Indagatio Didactica, 8(1),

158–174. https://doi.org/10.34624/id.v8i1.3148

Cebrián-Robles, D.,

Pérez-Galán, R., & Quero-Torres, N. (2019). Estudio comparativo de la

evaluación a través de ejercicios sobre texto y vídeo para la identificación de

elementos de una investigación científica. Digital

Education Review, 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1344/der.2019.35.81-96

Chui-Lami, & Habil, H. (2021). The Use of Video

Annotation in Education: A Review. Asian Journal of University Education, 17(4),

84–94. https://doi.org/10.24191/ajue.v17i4.16208

Craig, D. H. (2021). Participatory Media Literacy in

Collaborative Video Annotation. TechTrends, 860-873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00632-6

Crespo-Miguel, M., &

Sánchez-Saus Laserna, M. (2020). Píldoras formativas para la mejora educativa

universitaria: el caso del Trabajo de Fin de Grado en el Grado de Lingüística y

Lenguas Aplicadas de la Universidad de Cádiz. Education

in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 21, 10. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.22370

Day, I., Saab, N., & Admiraal, W. (2022). Online

peer feedback on video presentations: type of feedback and improvement of

presentation skills. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(2),

183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.1904826

Evi-Colombo, A., & Cattaneo, A. (2020). Technical

and Pedagogical Affordances of Video Annotation: A Literature Review. Journal

of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 29(3), 193–226. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/215718/

Fernández-Batanero, J. M.,

Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernández-Cerero, J., & García-Martínez, I. (2020). Digital

competences for teacher professional development. Systematic review. European

Journal of Teacher Education, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1827389

Gallego-Arrufat, M. J. (2015).

Actitud del alumnado hacia la investigación en educación: Trabajando con vídeos

en estudios de grado. Revista de Ciències de l’Educació, 1, 8–29. http://revistes.publicacionsurv.cat/index.php/ute

Hefter, M. H., & Berthold, K. (2020). Preparing

learners to self-explain video examples: Text or video introduction? Computers

in Human Behavior, 110, 106404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106404

Joksimović, S., Dowell, N., Gašević, D.,

Mirriahi, N., Dawson, S., & Graesser, A. C. (2018). Linguistic

characteristics of reflective states in video annotations under different

instructional conditions. Computers in Human Behavior, 96, 211-222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.003

Kennedy-Kam, C. H. (2021). Using classroom video-based

instruments to characterise pre-service science teachers’ incoming usable

knowledge for teaching science. Research in Science & Technological

Education, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2021.1872517

Kemczinski, A., Cebrián-Robles, D. &

Duarte-Freitas, M. (2017). Difusión

y colaboración del conocimiento científicos mediante anotaciones en

vídeo-póster. Enseñanza de Las Ciencias, 0, 347–354. https://ddd.uab.cat/record/184630

Leung, K. C., & Shek, M.

P. (2021). Adoption of video annotation tool in enhancing

students’ reflective ability level and communication competence. Coaching:

An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 14(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521882.2021.1879187

Koedinger, K. R., Kim, J., Jia, J. Z., McLaughlin, E.

A., & Bier, N. L. (2015). Learning is Not a Spectator Sport: Doing is

Better than Watching for Learning from a MOOC. Proceedings of the Second (2015)

ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale, 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1145/2724660.2724681

Leiva-Núñez, J. P., Ugalde

Meza, L., & Llorente-Cejudo, C. (2018). El modelo TPACK en la formación

inicial de profesores: modelo Universidad de Playa Ancha (UPLA), Chile. Pixel-Bit.

Revista De Medios y Educación, (53), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i53.11

Luna, M. J., & Sherin, M. G. (2017). Using a video

club design to promote teacher attention to students’ ideas in science. Teaching

and Teacher Education, 66, 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.04.019

Marçal, J., Borges, M. M., Viana, P., & Carvalho,

P. (2020). Aprender

la Física a través de anotaciones de vídeos en línea. Education

in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 21, 21–21. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23373

Martínez, D. & Cebrián, D.

(2019). Análisis videográfico para la evaluación de los aprendizajes en las

prácticas externas de la formación inicial de docentes de secundaria. Revista

Universitaria de Investigación Educativa, 55(2), 457–477. https://bit.ly/3oySoX8

McFadden, J. (2019). Transitions

in the Perpetual Beta of the NGSS: One Science Teacher’s Beliefs and Attempts

for Instructional Change. In Journal of Science Teacher Education, 30(3),

229–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560x.2018.1559559

Mei-Po S. M., Leung, K. & Yee-Lap To, P. (2021).

Using a video annotation tool to enhance student-teachers’ reflective practices

and communication competence in consultation practices through a collaborative

learning community. Education and Information Technologies, 26(4),

4329-4352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10480-9

Mirriahi, N., Joksimović, S., Gašević, D.,

& Dawson, S. (2018a). Effects of instructional conditions and experience on

student reflection: a video annotation study. Higher Education Research

& Development, 37(6), 1245–1259. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1473845

Mirriahi, N., Jovanovic, J., Dawson, S., Gašević,

D., & Pardo, A. (2018b). Identifying engagement patterns with video

annotation activities: A case study in professional development. Australasian

Journal of Educational Technology, 34(1). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3207

Mirriahi, N., Jovanović, J., Lim, L.-A., &

Lodge, J. M. (2021). Two sides of the same coin: video annotations and in-video

questions for active learning. Educational Technology Research and

Development: ETR & D, 69(5), 2571–2588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10041-4

Nielsen, B. L. (2015). Pre-service teachers’

meaning-making when collaboratively analysing video from school practice for

the bachelor project at college. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3),

341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2014.983066

Nilsson, P., & Karlsson, G. (2019). Capturing

student teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) using CoRes and digital

technology. International Journal of Science Education, 41(4), 419–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1551642

Ó Gallchóir, C., O’Flaherty, J., & Hinchion, C.

(2018). Identity development: what I notice about myself as a teacher. European

Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1416087

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron,

I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L.,Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A.,

Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu,

M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S.,McGuinness, L.A., Stewart,L.A., Thomas, J.,...Moher, D. (2021).

The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic

reviews. BMJ,

71, 1-9.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pertegal-Vega, M.,

Oliva-Delgado, A., & Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A. (2019). Revisión sistemática

del panorama de la investigación sobre redes sociales: Taxonomía sobre

experiencias de uso. Comunicar, 60(27), 81-91. https://doi.org/10.3916/C60-2019-08

Pérez-Torregrosa, A. B.,

Díaz-Martín, C., & Ibáñez-Cubillas, P. (2017). The

Use of Video Annotation Tools in Teacher Training. Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 237, 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2017.02.090

Perini, M., Cattaneo, A. A. P., & Tacconi, G.

(2019). Using Hypervideo to support undergraduate students’ reflection on work

practices: a qualitative study. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0156-z

Po-Sheng Ch., Hsin-Chin, Ch., Yueh-Min, H., Chia-Ju,

L., Ming-Chi,L., & Ming-Hsun, Sh. (2018). A video annotation learning

approach to improve the effects of video learning. Innovations in Education

and Teaching International, 55(4), 459–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1213653

Poquet, O., Lim, L., Mirriahi, N., & Dawson, S.

(2018). Video and learning: a systematic review (2007--2017). Proceedings of

the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge,

151–160. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170358.3170376

Rich, P. J., & Hannafin, M. (2009). Video

Annotation Tools: Technologies to Scaffold, Structure, and Transform Teacher

Reflection. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108328486

Ruiz-Rey, F., Cebrián-Robles, V., &

Cebrián-de-la-Serna, M. (2021a). Análisis

de las videoguías con anotaciones multimedia. Campus Virtuales, 10(2), 97–109. https://bit.ly/3cL1hdv

Ruiz-Rey, F. J.,

Cebrián-Robles, V. & Cebrián-de-la-Serna, C. (2021b). Redes profesionales

en tiempo de Covid19: compartiendo buenas prácticas para el uso de TIC en el

prácticum. Revista Practicum, 6(1),

7–25. https://doi.org/10.24310/RevPracticumrep.v6i1.12283

Sezen-Barrie, A., Tran, M.-D., McDonald, S. P., &

Kelly, G. J. (2014). A cultural historical activity theory perspective to

understand preservice science teachers’ reflections on and tensions during a