Mapping the Use of Neurotechnology in Education

from an Ethical Perspective

Mapeo sobre el uso de la Neurotecnología en

educación desde una perspectiva ética

Dra. Inmaculada

García-Martínez. Profesora Ayudante Doctora. Facultad de

Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dra. Inmaculada

García-Martínez. Profesora Ayudante Doctora. Facultad de

Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dra. Norma

Torres-Hernández. Profesora Sustituta interina. Facultad de

Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Jaén. España

Dra. Norma

Torres-Hernández. Profesora Sustituta interina. Facultad de

Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Jaén. España

Dña. Irene

Espinosa-Fernández. Doctoranda. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dña. Irene

Espinosa-Fernández. Doctoranda. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de Granada. España

Dña. Lara

Checa-Domene. Doctoranda. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de

Granada. España

Dña. Lara

Checa-Domene. Doctoranda. Facultad de Ciencias de la

Educación. Universidad de

Granada. España

Received: 2023/04/27 Revised: 2023/06/20 Accepted: 2023/08/10 Preprint:

2023/08/26 Published: 2023/09/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Torres-Hernández, N., García-Martínez, I., Espinosa-Fernández,

I., & Checa-Domene, L. (2023). Mapping the

Use of Neurotechnology in Education from an Ethical Perspective

[Mapeo sobre el uso de la Neurotecnología en

educación desde una perspectiva ética]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de

Medios y Educación, 68, 273-304. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.100461

ABSTRACT

Neurotechnology has a long tradition in the clinical field.

However, it is increasingly present in the field of education. This review aims

to provide an overview of research based on educational neurotechnology that

considers the ethical component in its design and implementation. For this

purpose, the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the

databases Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC and Science Direct were followed. After

the double review process with the inclusion and exclusion criteria considered,

the review sample was set at 12 articles. The main findings found support the

effectiveness of using neurotechnology in the field of education, especially

for students with special educational needs. It also shows its usefulness in

the acquisition of instrumental learning and for obtaining improvements in

different areas of development such as attention, memory

and motivation. However, in addition to their implicit benefits, the inclusion

of educational neurotechnology implies a number of

challenges for both teachers and educational institutions, related to training,

ethics and the administrative and economic management of these resources and

tools. Similarly, despite the existence of different theoretical studies, there

is a call for more empirical studies on this topic.

RESUMEN

La neurotecnología posee una gran tradición desde el

ámbito clínico. Sin embargo, cada vez está más presente en el campo de la

educación. Este trabajo de revisión trata de ofrecer una panorámica sobre las

investigaciones basadas en neurotecnología educativa que consideren el

componente ético en su diseño e implementación. Para ello, se siguieron las

directrices PRISMA para la realización de revisiones sistemáticas y

metaanálisis en las bases de datos Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC y Science

Direct. Tras el proceso de doble revisión con los criterios de inclusión y

exclusión considerados, la muestra de la revisión quedó fijada en 12 artículos.

Los principales hallazgos encontrados reivindican la efectividad de utilizar la

neurotecnología en el campo de la educación, especialmente para el alumnado con

necesidades educativas especiales. Asimismo, muestra su utilidad para la

adquisición de aprendizajes instrumentales y obtener mejoras en diferentes

ámbitos de desarrollo como la atención, la memoria o la motivación. Sin

embargo, además de los beneficios implícitos, la inclusión de la

neurotecnología educativa implica una serie de retos tanto para el profesorado,

como para las instituciones educativas, relacionadas con la formación, la ética

y la gestión administrativa y económica de estos recursos y herramientas. De

igual modo, pese a existir diferentes estudios de naturaleza teórica, se hace

un llamado para la realización de más estudios empíricos sobre esta temática.

KEYWORDS· PALABRAS CLAVES

Educational neurotechnology; ethics; individualized

instruction; education; systematic review; teaching and training

Neurotecnología educativa; ética;

enseñanza individualizada; educación; revisión sistemática; enseñanza y formación

1. Introduction

1.1 An approach to the

concept of neurotechnology

Over the past few

years, the linking of education with technology is a reality that provides an understanding

of how technology may influence students' personal development, enabling

meaningful, contextualised and situated learning between the real and virtual

world, and fostering the emergence of rich learning experiences (Cox, 2021;

Raza and Khan, 2021). This understanding would not be possible without the

interdisciplinary work of diverse sciences whose studies help to understand how

the brain supports thinking, learning and remembering.

In parallel with the

development of technology, cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychology (Ardila

et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Garza, 2016), as well as the use of neuroimaging

techniques, together with other types of electrophysiological techniques

(Roebuk-Spencer et al., 2017) contribute significantly to the knowledge of

brain processes that currently allow us to know where in the brain, when and

how they are integrated for better learning (Reber, 2013).

According to Bastidas

(2021), neurotechnology derives from a set of tools that serve to manipulate,

record, measure and obtain information from the brain, in order to analyse and

influence the human nervous system. As Fanelli and Ghezzi (2021) point out,

this requires the use of artificial devices integrated into neural tissue to

mitigate and respond to various needs ranging from transient monitoring of

biological parameters to transient neurostimulation.

Neurotechnology

linked to the field of education raises the idea of a new approach to learning

with a scientific and multidisciplinary approach (Pradas 2017). Thus, educational

neurotechnology is the approach to the use of technology in education, in which

neural processing is properly interpreted (Pradas, 2016). It is also a new

science of learning, which is based on knowledge about the functioning of the

human brain and the methodology used in the use of technology in the classroom

(Privitera and Du, 2022).

The progress made in

neuroscience and cognitive psychology has given rise to a neuroscience of

education (Dehaene, 2007) with great potential for optimising teaching

strategies and adapting them to the different brain functionings of students at

any stage of their studies.

Pradas (2017)

considers that if a teacher wants to design a roadmap for the learning support

of their students from the perspective of neurotechnology, they should take

into account three different approaches to the learning process from the

perspective of neuropsychology and technology. Thus, the need for a) a

methodological change in which appropriate methodological strategies are

applied; b) the application of technology with a pedagogical and not merely

instrumental intention, with technological resources and at the appropriate

time and adapted to the methodology and; c) using the necessary and sufficient

technological advances to personalise student learning.

1.2. Possibilities for the use of neurotechnology in education

The inclusion of

educational neurotechnology requires an interdisciplinary effort to explore all

the possibilities that neuroscience can bring to instructional processes (Johnson

et al., 2021). However, its high complexity presents a challenge for

researchers and practitioners in its full implementation in the educational

setting. So far, the contributions made by neurotechnology to education in

different studies allow a better understanding regarding the neuropsychological

bases of the use of technology for the attention of visual, auditory and

sensory developmental disabilities. They help teachers in the design and

introduction of methodological changes in the classroom based on gamification,

the inverted classroom or the Flipped Classroom. Likewise, through the

knowledge of how the brain works, it offers guidelines for the design and

implementation of programmes to improve attention, the development of visual

skills, the implementation of motor or balance programmes, for the development

of language, memory or creativity (Williamson, 2019). In turn, for education

professionals, such as pedagogues, psychologists, teachers, hearing and speech

therapists, it provides information on how students can be helped to overcome

learning difficulties in matters related to language, attention or social

skills.

In short,

neurotechnology seeks to redefine the existing educational and technological

tradition in terms of monitoring and intervention in clinical and non-clinical

settings such as education, with great promise for improving mental health,

well-being and productivity.

1.3. Ethical issues in educational neurotechnology.

Recent advances in neurotechnology

and artificial intelligence are allowing greater and faster access to the

information accumulated in people's brains, thus giving machines the ability to

read, process, interpret and manipulate our mental impulses, and may even

modify how we think of ourselves as humans.

Neurotechnological

applications, if misused or misapplied, can create unprecedented forms of

intrusion into people's private sphere, cause physical or psychological harm or

unduly influence their behaviour (Ienca and Adorno, 2017). Even if Williamson

(2019), raises the existence of some scientific scepticism about the technology

and concerns around the privacy and ethics of brain data, there is now clear

concern that the low ecological validity of standard cognitive neuroscience

studies (Matusz et al., 2019; van Atteveldt et al., 2018) are increasingly

becoming common in educational settings.

Yuste (2019)

considers that although neurotechnology is studied with an altruistic and

humanistic vocation, the technologies may well be used for the opposite

purposes, which raises ethical and social issues. Especially when neuroscience,

neurotechnology and artificial intelligence are brought together. As Bastida

(2021) points out, the aim is to protect against the abuses that can occur with

the use of new neurotechnology and artificial intelligence techniques.

In this regard, the

Recommendation on Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnology (OECD, 2022) is the

first international standard in the field of neurotechnology that seeks to guide

government policies and innovators in this field, anticipating and defining the

ethical, legal and social challenges raised by this new approach. To this end, it includes nine principles

focused on: promoting responsible innovation, prioritising safe assessment,

promoting inclusion, fostering scientific collaboration, promoting social

deliberation, empowering the capacity of oversight and advisory bodies,

safeguarding personal brain data, promoting a culture of governance and trust

in the public and private sectors, and how to anticipate and monitor the

improper or intentional use of information from neurotechnology-supported

studies and practices.

In turn, Ienca and

Adorno (2017), concerned about the ethical problems that arise from the union

between neutotechnology, neuroscience and artificial intelligence. They suggest

that a good way to address this issue is through neuro-rights, which protect

citizens in general and therefore students, in aspects related to mental

privacy and consent, the right to identity and decision-making, the enhancement

of cognitive activities, and the absence of biases.

Tubig and McCisker

(2020) raise two central questions around which ethical issues revolve in

research on new neurotechnologies. On the one hand, ethical reflexive activity

as a transformative and respectful mechanism for vulnerable people to

articulate, analyse and evaluate the assumptions and values underlying

individual and institutional ethical actions and projects. On the other hand,

they start from what they refer to as burdens of trust defined as

vulnerabilities that can be assumed by the researcher when placing trust in

others in the face of the many individual and social risks in this type of

research.

van Atteveldt et al.,

(2019), propose a framework called Responsible Research and Innovation, which

originates from the intersection between technology assessment, ethics and

science policy, as a relevant systematic approach to engage parents in

educational practice. Using neurofeedback to alleviate ethical concerns and the

appropriateness of innovations brought by research on mind, brain and education

to adequately impact neurotechnology research.

Ethics in education

as Aguiton (2015) points out could become an instrument of governance that goes

beyond institutionalisation and proceduralisation. It needs to be made truly

operational and more ethically sensitive in order to reduce concerns on these

issues both among researchers and among those who participate before, during

and after the research.

Taking the above into

account, we can see how neurotechnology is in line with the teaching and

learning processes of today and the future in the short, medium and long term.

Despite being an emerging topic in the field of education, where there are

already some literature reviews (Privitera and Du, 2022; Williamson, 2019).

These have tried to deepen its approach in the educational field, trying to

analyse its potential, benefits and applicability in the reality of the

classroom, there are still questions to be resolved, such as the collection of

real experiences in educational institutions or the ethical challenges that

accompany its integration in the teaching and learning processes. Therefore,

the main objective of this review is to provide an overview of research on the

use of neurotechnology for teaching purposes from an ethical perspective. More

specifically, the aim is to: a) Identify interventions based on neurotechnology

developed at different educational stages; b) Examine the topics of research

involving neurotechnology; c) Examine the ethical risks that the use of

educational neurotechnology has for students; and d) Find out the benefits and

drawbacks of neurotechnology for student learning.

Accordingly, the research questions proposed are the

following:

Q1: Which neurotechnology-based interventions have

been developed in the different educational stages?

Q2: What are the topics of the neurotechnology-based

interventions carried out?

Q3: What ethical risks does the use of educational

neurotechnology have for students?

Q4: What are the benefits and drawbacks of

neurotechnology for student learning?

2. Method

The literature review conducted followed the

recommendations promoted by the PRISMA statement developed by Page et al.

(2021). The PRISMA statement is to guide authors in the preparation of

protocols, to plan meta-analyses and systematic reviews, which are able to

summarise the totality of data from studies on the possible effects of

interventions, through a set of items for inclusion in the protocol.

2.1. Search strategy

For the search of articles and publications it was

decided to consult the SCOPUS, WOS, ERIC and SCIENCE DIRECT databases, as these

are the main databases where most of the relevant studies in the area of

education are located. The date on which the search for the different articles

was carried out was 24-11-2022.

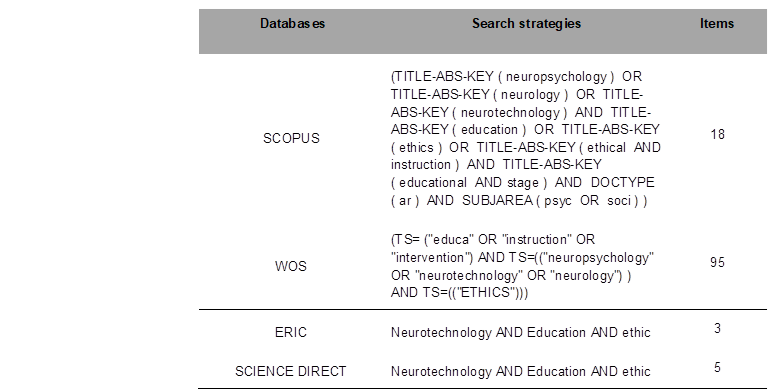

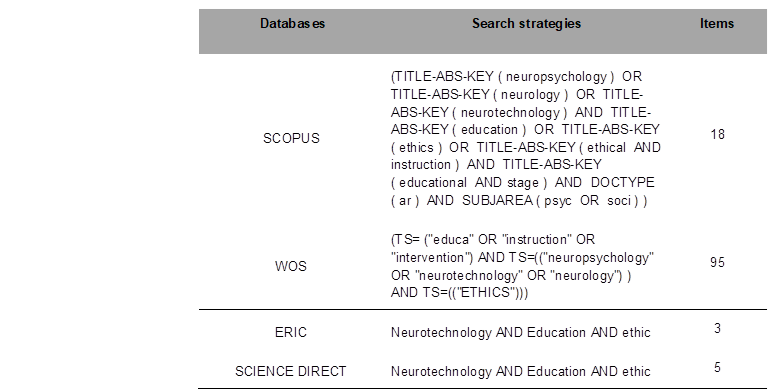

Table 1 shows the search equations used in both

databases, as well as the number of references obtained in each one. For the

search for information, the results obtained were filtered by the type of

document "journal article", as the aim was to make the research more

scientific by selecting a peer-reviewed document. Given the emergence of the

topic, it was decided not to restrict the search to any time interval.

Table 1

Databases, search strategy and references

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the search process,

the following inclusion criteria were followed: a) articles, b) written in

English or Spanish, c) belonging to the field of education, d) focused on

neurotechnology, e) ethical considerations, and f) the participants in the

sample must be students at any stage of education.

On the other hand, the exclusion criteria that were

followed were: a) articles in which participants were other than students, b)

subject matter other than educational neurotechnology, c) general themes, d)

did not address ethical issues, and e) were not contextualised in the teaching

and learning processes.

2.3. Selection process

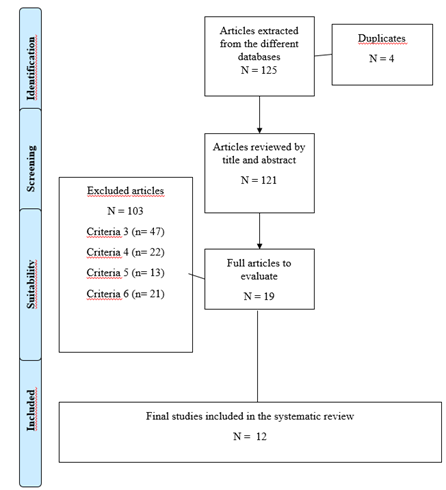

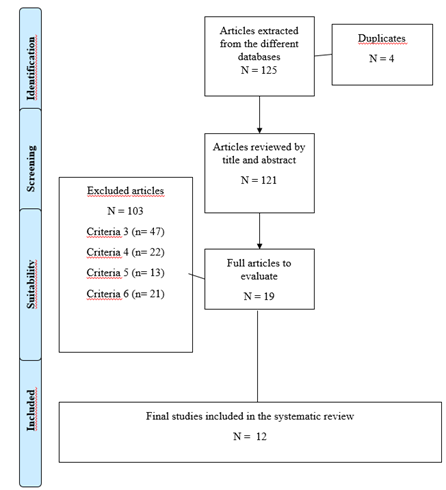

After entering the descriptors specified above, a

total of 125 references were obtained (figure 1), with 4 of them being

discarded as they were duplicates. The manuscript review process was structured

in a double phase. The first phase involved reading the title and abstract,

where the manuscripts were screened according to compliance with the previously

defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Secondly, a detailed and

comprehensive reading of the full manuscripts included in the first phase was

carried out, with the intention of selecting the research sample. Specifically,

in the first phase, 103 articles were discarded, the reasons for which are specified

in figure 1. In the second phase, 19 manuscripts were read in their entirety

and, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the sample was

reduced to 12.

Figure 1

Flowchart

3. Results

3.1 Characterisation of the

articles included

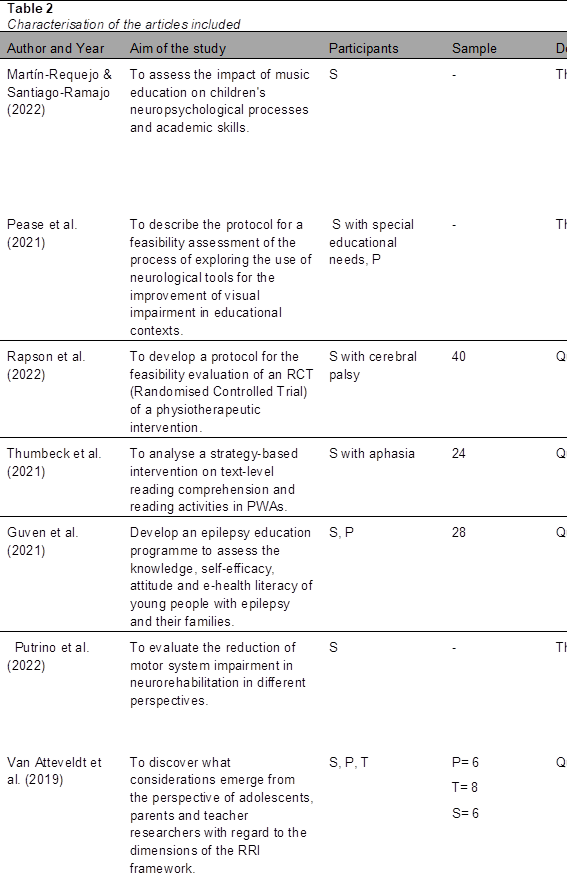

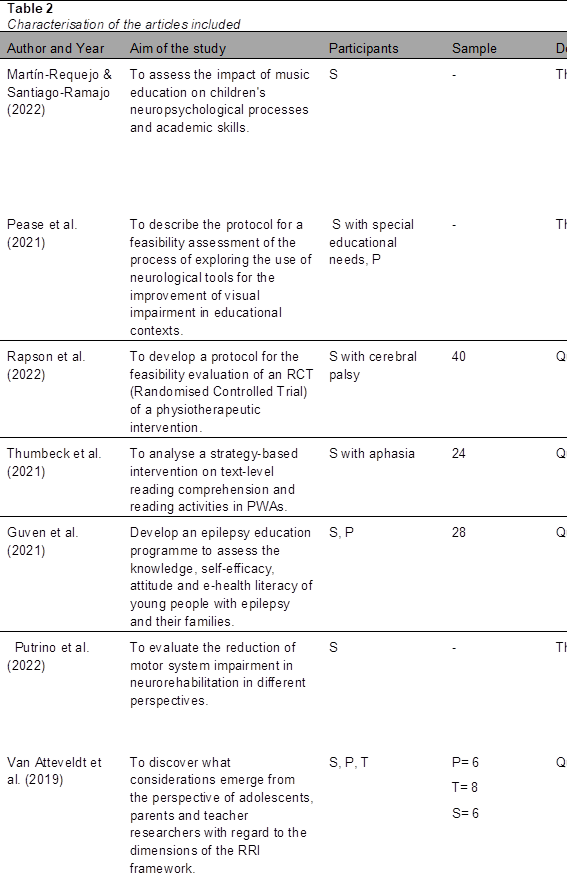

The review process conducted yielded 12 articles that met

the determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Table 2 below lists the main

characteristic features of each of the included studies.

Description of the items included

The increasing

emergence of neuro-technological tools nowadays means a generalised advance in

the framework of action in all contexts of everyday life, as in the case of

education. Privitera and Du (2022) generated an action design with innovation

tools, which concluded that neurotechnology applied to education is a promising

resource that enhances the attention, commitment and collaborative dynamics of

students.

This involves the

introduction of a new work dynamic that requires training. In this vein,

Bergaliev and Mazurov (2020) conducted an implementation framework for training

and introducing primary school pupils to the use and

mastery of new types of high-tech products as a feasibility project for the

acceptance of such tools in regulations and legislation in the Russian context.

The emergence of such novel materials requires impact assessment and

considerations on the part of the educational community. Accordingly, Van

Atteveldt et al. (2019) shed light on this issue with a qualitative case study

design collecting the impressions of families, teachers and researchers on the

investigation of the dimensions of the RRI framework, considering the school as

an agent anticipating possible impacts of social changes and innovations.

Neurotechnology proves to be a useful tool within

education, both for improvement and support, as in the case of people

undergoing neurorehabilitation, being a viable resource in the modulation of

learning and behaviour of subjects with neurological injuries, improving

comprehensive learning and the process of "non-recovery" (Putrino et

al. 2022); or on the other hand, in the context of SEN, Pease et al. (2021)

developed a protocol with neurotechnological tools for the improvement of

visual impairments, expecting positive results in the performance of students

with visual impairment and ratifying the need for collaboration at the clinical

and educational level for successful implementation.

Wang et al. (2019) built a helmet of electrical

signals from neurons to record the students' ability to concentrate and process

them in an interactive spaceship interface, in which the greater the

concentration, the more progress the ship made and the more positive the

preamble to learning motivation and scientific skills. Consistent with this is

the evidence collected by Requejo & Ramajo (2022), who advocate the impact

of musical practice or the development of musical skills as an element that

enhances neuroplasticity, increasing neuronal activity and generating positive

effects on the neuropsychological processes and academic skills of children

musicians.

Neurotechnological interventions have highlighted the

potential of their use in a variety of contexts. Rapson et al. (2022) propose

an action protocol in the physiotherapeutic context in RCT (Randomised

Controlled Trial) on students with cerebral palsy as a suitable, viable and feasible

intervention tool. In particular, Guven et al. (2021) generate a programme

dedicated to young people with epilepsy and their families, improving and

evaluating knowledge, anticonvulsant self-efficacy, attitude and e-health

literacy through a WEEP website. It is not only a framework for action and

intervention but also a tool to assist in the improvement of skills. An example

of this is the study by Thumbeck et al. (2021), who analysed neurotechnological

strategies used in PWA (People with aphasia) to assess improvements in reading

comprehension and reading activities by means of pre-test and post-test design,

registering significant improvements.

Table 2

Charaterisation of the artides included

Note: S: Students; P:

Parents; T: Teachers; Th: Theoretical; Qual: Qualitative; Quan: Quantitative.

It can be observed that neurotechnology is a

guarantee, in most cases, of positive results, but it can also become a source

of feedback in educational processes. Sorochinski et al. (2022) presented

neuro-feedback within the learning process to enhance the ability to monitor

attention, thus improving the acquisition of information and concentration,

obtaining significantly positive results. On the other hand Pillete et al.

(2020) who proposed a Brain-Computer Interface that, based on mental

imagination, reflected through phrases and combinations of facial expressions

feedback in the processes of improving communication, achieving improvements in

the predisposition for group work or in the ability to learn and memorise.

4. Discussion and

conclusions

The aim of this review was to provide an overview of

research on the use of neurotechnology for teaching purposes from an ethical

perspective. After an exhaustive search process in different databases, the

review process yielded 12 articles that met the established parameters. The

following is an attempt to answer the four research questions that motivated

this review.

Q1: Which neurotechnology-based interventions have

been developed in the different educational stages?

The present research does not provide evidence on

different educational stages, except for two studies located in primary

education (Bergaliev and Mazurov, 2020; Wang et al., 2019). On the contrary,

efforts have been concentrated on improving different domains of developmental

and instrumental learning with students with special educational needs (Guven

et al., 2021; Rapson et al., 2022; Thumbeck et al., 2021), especially those

with sensory or cognitive diversity. These findings imply that the inclusion of

neurotechnology with an educational approach goes in parallel to the

educational interventions designed and implemented by educational institutions,

acting as a complement to them (Antonenko, 2019). In this line, considering

that it is a learning-enhancing incentive (Requejo & Ramajo, 2022) and

taking into account the cognitive and developmental theories on educational

technology (Rudolph, 2017), it has a special place in the primary and secondary

education stages. However, if we consider different degrees of affection within

the group of special educational needs, neurotechnology can also be implemented

in other educational stages and in non-formal education modalities. In any

case, studies such as the one developed by Demera-Zambrano et al. (2021) showed

the potential that neurotechnology offers for the attention of the group with

special educational needs from the point of view of fifty practising teachers,

as they allow a greater understanding of how their students learn, as well as

the wide variety of rhythms and abilities that they possess.

Q2: What are the topics of the neurotechnology-based

interventions carried out?

The studies included in the review are diverse in

terms of the topics covered. Thus, we find research aimed at improving

students' reading and writing skills and comprehension (Thumbeck et al., 2021),

communication (Pillete et al., 2022), memory and cognition (Sorochinski et al.,

2022), attention (Wang et al., 2019), motivation and even strengthening more

social aspects such as collaboration (Privitera and Du, 2021). The interdisciplinary

nature that distinguishes this technology means that it does not fit into any

specific area of knowledge. In this way, a comprehensive view where the typical

instructional processes belonging to the different knowledge areas are

alternated in a complementary way to interventions of this type, could be the

success in achieving the full inclusion and integral development of all

students.

Q3: What ethical risks does the use of educational

neurotechnology have for students?

All the research included in the review has pointed

out to a greater or lesser extent that the use of neurotechnology can pose a

personal risk for students, as it can undermine their intimacy, privacy and

right to privacy and even run the risk of exclusion. Along these lines, knowing

how a student's brain works, knowing their learning style and ability, using

physiological measures can lead to "labelling" in an already diverse

student body, which can lead to unintentional discriminatory measures.

Likewise, neuroethics advocates a holistic consideration of the person, where

not only the objective data provided by the equipment used for teaching or

clinical purposes is taken into account, but also the context in which the

person develops (Shook et al., 2014).

Q4: What are the benefits and drawbacks of

neurotechnology for student learning?

Despite the scarce empirical evidence found, the use

of neurotechnology has a large number of benefits for students. Firstly, it

adheres to the trend of developing individualised learning processes tailored

to the characteristics of the learner (Kuch et al., 2020). In turn, due to the

plasticity of the brain, the way to incorporate neuotechnology in education

will have to pass through its potential for brain stimulation (Williamson,

2019), favouring the construction of neuronal synapses, especially in those

students with functional diversity or cognitive impairment (Guven et al., 2021;

Rapson et al., 2022; Pillete et al., 2022; Thumbeck et al., 2021; Wang et al.,

2019). However, there also remain certain challenges that may hinder the

potential that neurotechnology can offer in the field of education. First of

all, teacher training needs to be highlighted. Despite major advances in the

professionalisation of teachers in terms of digital literacy (Fernández-Batanero

et al., 2020), there are still major training gaps and attitudes that are not

very proactive in its implementation. While it is true that the prevalence of a

certain unease or fear of the new or unknown may cause some reluctance among

teachers whose functions have multiplied in recent years, what must take

precedence is the overall well-being of students. Secondly, the high cost of

using this equipment should not be overlooked, and not all educational

institutions can afford it. This issue opens the debate on the need for

national and supranational policies to invest in education, with a view to

equipping them with the resources and technologies necessary to design, develop

and implement quality teaching and learning processes that favour equity for

all students, especially the most disadvantaged.

In any case, the systematic review provides guidance

on the state of the art on the integration of neurotechnology in the field of

education. Unfortunately, this topic is in line with the trend of developments

in education. Many of the incorporations that are taking place in teaching and

learning processes and in the reality of the classroom come from other areas of

knowledge. This milestone hinders and/or slows down their full inclusion,

especially in the early stages. While it is true that neurotechnology can

become an important ally in the design of an effective educational response,

time and effort are required to train the education professionals who must lead

such initiatives. Furthermore, the lack of empirical evidence, despite the

existence of an important body of theoretical studies, makes it impossible to

extrapolate the real benefits that neurotechnology can offer to different areas

of knowledge taught by educational institutions. In this regard, progress along

these lines and contributing to the emergence of empirical research in

different subjects and at different stages could help to identify keys to

success for the development of good educational practices. At the same time,

the results obtained have revealed the enormous potential that neurotechnology

can offer in the field of Special Education, and so the proliferation of

studies based on educational interventions using neurotechnology with different

groups with specific educational support needs could also contribute fully to

improvements in this field.

5. Funding

This publication is part of the I+D-+I project,

PID2019-108230RB-I00, funded by MCIN/ AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Mapeo sobre el uso de la Neurotecnología

en educación desde una perspectiva ética

1. Introducción

1.1.

Aproximación al concepto de neurotecnología

En los últimos años, la vinculación

de la educación con la tecnología es una realidad que permite comprender la

manera de cómo ésta puede influir al desarrollo personal del alumnado,

facilitar un aprendizaje significativo, contextualizado y situado entre el

mundo real y virtual, fomentando la aparición de ricas experiencias de

aprendizaje (Cox, 2021; Raza & Khan, 2021). Esta comprensión no sería

posible sin el trabajo interdisciplinar de diversas ciencias que con sus

estudios ayudan a comprender la forma sobre cómo el cerebro ayuda a pensar,

aprender y recordar.

Con un desarrollo paralelo a

la tecnología, la neurociencia cognitiva y la neuropsicología (Ardila et al.,

2010; Rodríguez-Garza, 2016), así como la utilización de técnicas de imágenes

neuronales, junto a otro tipo de técnicas electrofisiológicas (Roebuk-Spencer

et al., 2017) contribuyen de manera importante al conocimiento sobre los

procesos cerebrales que en la actualidad permiten conocer en qué parte del

cerebro, cuándo y cómo se integran para un mejor aprendizaje (Reber, 2013).

De acuerdo con Bastidas

(2021), la neurotecnología deriva en un conjunto de herramientas que sirven

para manipular, registrar, medir y obtener información del cerebro, con el fin

de analizar e influir sobre el sistema nervioso del ser humano. Para ello, como

señalan Fanelli y Ghezzi (2021) se requiere del uso de dispositivos

artificiales integrados en el tejido neural para mitigar y dar respuesta a

diversas necesidades que van desde la monitorización transitoria de parámetros

biológicos hasta la neuroestimulación transitoria.

La neurotecnología vinculada

al ámbito educativo, plantea la idea de un nuevo enfoque con el que se quiere

abordar el aprendizaje con un enfoque científico y multidisciplinar (Pradas

2017). De esta manera, la neurotecnología educativa es el enfoque del uso de la

tecnología en el ámbito educativo, en el que se interpreta adecuadamente el

procesamiento neuronal (Pradas, 2016). Asimismo, se trata de una nueva ciencia

del aprendizaje, cuya base se tiene en el conocimiento sobre el funcionamiento

del cerebro humano y la metodología utilizada en el empleo de la tecnología en

el aula (Privitera & Du, 2022).

Los progresos originados por

las neurociencias y la psicología cognitiva han originado una neurociencia de

la educación (Dehaene, 2007) con altas posibilidades de optimizar estrategias

de enseñanza y adaptarlas a los diferentes funcionamientos cerebrales del

alumnado en cualquier etapa de sus estudios.

Pradas (2017) considera que,

si un docente quiere diseñar una hoja de ruta para ayudar al aprendizaje de su

alumnado desde la perspectiva de la neurotecnología, deberá tener en cuenta

tres enfoques diferentes: sobre el proceso de aprendizaje, desde la perspectiva

de la neuropsicología y de la tecnología. De esta manera, se evidencia la necesidad

de a) un cambio metodológico en el que se apliquen adecuadas estrategias

metodológicas; b) la aplicación de la tecnología con una intención pedagógica y

no meramente instrumental, con recursos tecnológicos y en el momento pertinente

y adaptado a la metodología y; c) utilizar los avances tecnológicos necesarios

y suficientes para personalizar el aprendizaje del alumnado.

1.2.

Posibilidades de uso de la neurotecnología en

Educación.

La inclusión de la

neurotecnología educativa exige de un esfuerzo interdisciplinar para explorar

todas las posibilidades que la neurociencia puede aportar a los procesos

instruccionales (Johnson et al., 2021). Sin embargo, su elevada complejidad

supone un reto para investigadores y profesionales en su completa implementación

en el ámbito educativo. Hasta el momento, los aportes realizados de la

neurotecnología a la educación en diferentes estudios, permiten comprender

mejor acerca de las bases neuropsicológicas del uso de la tecnología para la

atención a discapacidades visuales, auditivas y de desarrollo sensorial. Ayudan

al profesorado en el diseño e introducción de cambios metodológicos en el aula

basados en la gamificación, el aula invertida o el Flipped Classroom. Igualmente, mediante el conocimiento que se

tiene del funcionamiento del cerebro, ofrece pautas para el diseño e

implementación de programas para la mejora de la atención, el desarrollo de

habilidades visuales, la puesta en práctica de programas de motricidad o

equilibrio, para el desarrollo del lenguaje, la memoria o la creatividad

(Williamson, 2019). A su vez, a los profesionales de la educación, tales como

pedagogos, psicólogos, profesorado, terapeutas de la audición y lenguaje les

aporta el cómo se puede ayudar al alumnado a superar dificultades del aprendizaje

en cuestiones relacionadas con el lenguaje, la atención o el área social.

En definitiva, la

neurotecnología busca una redefinición de lo existente en el campo educativo y

la tradición tecnológica, en términos de seguimiento e intervención en entornos

clínicos y entornos no clínicos como los educativos, con grandes promesas para

mejorar la salud mental, el bienestar y la productividad.

1.3.

Cuestiones éticas en la neurotecnología educativa.

Los recientes avances en

neurotecnología e inteligencia artificial están permitiendo un acceso mayor y

más rápido a la información acumulada en el cerebro de las personas otorgándole

capacidad a las máquinas de leer nuestros impulsos mentales, procesarlos,

interpretarlos y manipularlos, pudiendo alterar, incluso nuestro concepto de

ser humano.

Las

aplicaciones neurotecnológicas, si se utilizan mal o

se aplican de forma inadecuada, pueden crear formas de intrusión sin

precedentes en la esfera privada de las personas, causar daños físicos o

psicológicos o influir indebidamente en su comportamiento (Lenca & Adorno,

2017). Aun cuando Williamson (2019), plantea la existencia de cierto

escepticismo científico sobre la tecnología y las preocupaciones en torno a la

privacidad y la ética de los datos cerebrales, hoy existe una clara

preocupación por la baja validez ecológica de los estudios estándar de

neurociencia cognitiva (Matusz et al., 2019; van Atteveldt et al., 2018) son cada vez más frecuentes en el

ámbito educativo.

Yuste (2019) considera que la

neurotecnología si bien se estudia con vocación altruista y humanista, las

tecnologías bien pueden usarse con objetivos contrarios, por lo que con ello se

plantean problemas éticos y sociales especialmente cuando se unen la neurociencia,

la neurotecnología y la inteligencia artificial. Con ellos se busca, como

señala Bastida (2021), dar protección ante los abusos que se pueden dar con la

utilización de las nuevas técnicas de neurotecnología e inteligencia

artificial.

En ese sentido en la

Recomendación sobre innovación responsable en neurotecnología (OCDE, 2022), se

plantea la primera norma internacional en el ámbito de la neurotecnología con

la que busca orientar políticas de los gobiernos y a los innovadores en este

campo, anticipar y definir los retos éticos, jurídicos y sociales que plantea

este nuevo enfoque. Para ello recoge nueve principios centrados en: la

promoción de la innovación responsable, la priorización de una evaluación

segura, la promoción de la inclusión, el fomento de la colaboración científica,

la promoción de la deliberación social, la habilitación de la capacidad de los

órganos de supervisión y asesoramiento, la salvaguarda de datos personales

sobre el cerebro, la promoción de la cultura de la administración y la

confianza en sectores público y privado y la forma de anticipar y supervisar el

uso indebido o intencionado de la información proveniente de estudios y

prácticas apoyadas en la neurotecnología.

Por su parte, Lenca y Adorno

(2017) preocupados por los problemas éticos que surgen de la unión entre la

neutotecnología, la neurociencia y la inteligencia artificial plantean que una

buena manera de abordar esta cuestión es a través de los neuroderechos, con los

que se protege a la ciudadanía en general y por tanto al alumnado, en aspectos

relacionados con la privacidad mental y el consentimiento, el derecho a la

identidad y la toma de decisiones, del mejoramiento de las actividades

cognitivas, y la ausencia de sesgos.

Tubig y McCisker (2020)

plantean dos cuestiones centrales sobre las cuales giran aspectos éticos en la

investigación de nuevas neurotecnologías. Por un lado, la actividad reflexiva

ética como un mecanismo transformador y de respeto a las personas vulnerables

para articular, analizar y evaluar los supuestos y valores que subyacen en las

acciones y proyectos éticos individuales e institucionales. Por otra parten lo

que denominan como cargas de confianza definidas como vulnerabilidades asmibles

por el investigador al depositar la confianza en otros ante la gran cantidad de

riesgos individuales y sociales en este tipo de investigación.

Van Atteveldt et al., (2019),

proponen un marco de Investigación e Innovación Responsables [Responsible

Research and Innovation (RRI en inglés)], originado en la intersección entre la

evaluación tecnológica, la ética y la política científica, como un enfoque

sistemático pertinente para involucrar a la práctica educativa a los padres de

familia mediante el neurofeedback para paliar las preocupaciones éticas y la

conveniencia de las innovaciones aportadas por la investigación sobre mente,

cerebro y educación para un impacto adecuado en la investigación sobre

neurotecnología.

La ética en educación como

señala Aguiton (2015) podría convertirse en un instrumento de gobernanza que va

más allá de la institucionalización y procedimenatación. Se requiere hacerla

realmente operativa y con más sensibilidad ética para disminuir preocupaciones

en estas cuestiones tanto entre investigadores como entre quienes participan

antes, durante y después en la investigación.

Teniendo en cuenta lo

anterior, se observa cómo la neurotecnología va en la línea de los procesos de

enseñanza y aprendizaje del hoy y del futuro a corto, medio y largo plazo. En

sintonía, pese a tratarse de un tema emergente en el campo de la educación,

donde ya existen algunas revisiones de la literatura (Privitera & Du, 2022;

Williamson, 2019) que han tratado de profundizar en su aproximación en el campo

educativo, tratando de analizar su potencial, beneficios y aplicabilidad en la

realidad de las aulas, aún quedan cuestiones por resolver, tales como la

recogida de experiencias reales en las instituciones educativas o los desafíos

éticos que acompañan a su integración en los procesos de enseñanza y

aprendizaje. Por ello, el objetivo principal de esta revisión es realizar una

panorámica de las investigaciones realizadas sobre el uso de la neurotecnología

con fines docentes desde la perspectiva ética. De manera más específica, se

pretende: a) Identificar intervenciones basadas en neurotecnología

desarrolladas en diferentes etapas educativas; b) Examinar las temáticas de las

investigaciones que involucren a la neurotecnología; c) Examinar los riesgos

éticos que el uso de la neurotecnología educativa tiene para el alumnado; y d)

Conocer los beneficios e inconvenientes que la neurotecnología para el

aprendizaje del alumnado.

En esta línea, las preguntas

de investigación que se proponen en consonancia son las siguientes:

·

¿Qué intervenciones basadas en neurotecnología

se han desarrollado en las diferentes etapas educativas?

·

¿Sobre qué temáticas versan las intervenciones basadas

en neurotecnología realizadas?

·

¿Qué riesgos éticos tiene el uso de la neurotecnología educativa tiene para el alumnado?

·

¿Cuáles son los beneficios e inconvenientes que tiene

la neurotecnología para el aprendizaje del alumnado?

2. Metodología

La revisión de la literatura

realizada ha seguido las recomendaciones promovidas por la declaración PRISMA

desarrollada por Page et al. (2021).

La declaración PRISMA consiste

en orientar a los autores en la preparación de protocolos, para planificar

metaanálisis y revisiones sistemáticas, que sean capaces de resumir el conjunto

de los datos de estudios sobre los posibles efectos de las intervenciones, a

través de un conjunto de ítems de inclusión en el protocolo.

2.1.

Estrategia de búsqueda

Para la búsqueda de artículos

y publicaciones se decidió consultar en las fuentes de datos SCOPUS, WOS, ERIC

y SCIENCE DIRECT, ya que estas son las principales bases de datos, donde se

concentran la mayoría de los estudios relevantes en el área de educación. La

fecha en la que se llevó a cabo la búsqueda de los diferentes artículos fue el

24 de noviembre de 2022.

La tabla 1 recoge las

ecuaciones de búsqueda empleadas en ambas bases de datos, así como el número de

referencias obtenido en cada una. Para la búsqueda de información, los

resultados obtenidos se filtraron por el tipo de documento “artículo de

revista”, ya que se pretendía dotar a la investigación de cientificidad,

seleccionando un documento sometido a evaluación por pares. Dada la emergencia

del tópico, se optó por no restringir la búsqueda a ningún intervalo temporal.

Tabla 1

Base de datos, fórmulas

de búsqueda y referencias

|

Base de datos

|

Fórmulas de búsqueda

|

Ítems

|

|

SCOPUS

|

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (

neuropsychology ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( neurology ) OR

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( neurotechnology )

AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( education

) OR

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ethics )

OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ethical AND instruction ) AND

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( educational AND

stage ) AND DOCTYPE ( ar

) AND

SUBJAREA ( psyc OR soci ) )

|

18

|

|

WOS

|

(TS= ("educa"

OR "instruction" OR "intervention") AND TS=(("neuropsychology" OR

"neurotechnology" OR "neurology") ) AND

TS=(("ETHICS")))

|

95

|

|

ERIC

|

Neurotechnology AND Education AND ethic

|

3

|

|

SCIENCE DIRECT

|

Neurotechnology AND Education AND ethic

|

5

|

|

|

2.2.

Criterios de inclusión y exclusión

Para el proceso de búsqueda se

siguieron los siguientes criterios de inclusión: a) artículos, b) escritos en

inglés o español, c) que perteneciesen al área de educación, d) centrados en la

neurotecnología, e) matiz ético, y f) los participantes de la muestra deben ser

estudiantes de cualquier etapa educativa.

Por otro lado, los criterios

de exclusión que se siguieron fueron: a) artículos en los que aparezca otro

tipo de participantes que no sean estudiantes, b) temática distinta a la

neurotecnología educativa, c) artículos teóricos de revisión, d) no abordasen

las cuestiones éticas y e) que no se contextualizasen en los procesos de

enseñanza y aprendizaje.

2.3.

Proceso de selección

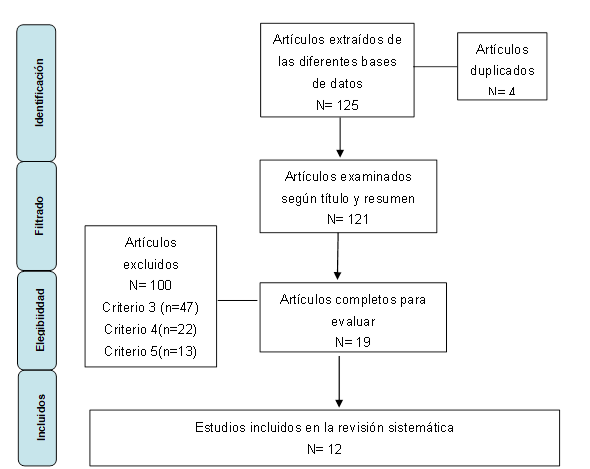

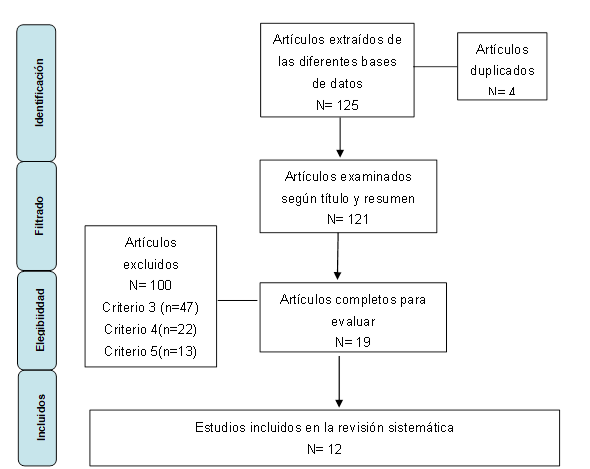

Tras introducir los

descriptores especificados anteriormente, se obtuvieron un total de 125

referencias (figura 1), siendo 4 de ellos desechados al estar duplicados. El

proceso de revisión de los manuscritos se estructuró en una doble fase. La

primera de ellas, atendía a la lectura del título y resumen, donde se realizó

un cribado de acuerdo al cumplimiento de los criterios de inclusión y exclusión

previamente definidos. En segundo lugar, se realizó una lectura detallada y

comprensiva de los manuscritos completos incluidos en la primera fase, con la

intención de seleccionar la muestra de la investigación. En concreto, en la

primera fase de desecharon 103 artículos, cuyas razones se especifican en la

figura 1. En la segunda fase, se procedió a la lectura completa de 19

manuscritos que, tras la aplicación de los criterios de inclusión y exclusión,

la muestra se concretó en 12.

Figura 1

Diagrama de flujo

3. Resultados

3.1.

Caracterización de los artículos incluidos

El proceso de revisión

realizado reportó 12 artículos que cumplían con los criterios de inclusión y

exclusión determinados. La tabla 2 recoge los principales rasgos

característicos de cada uno de los estudios incluidos.

3.2.

Descripción de los artículos incluidos

La creciente aparición de

herramientas neuro-tecnológicas en la actualidad supone un avance generalizado

en el marco de actuación de todos los contextos de la cotidianeidad como en el

caso de la educación. Privitera y Du (2022) generaron un diseño de actuación

con herramientas de innovación concluyendo que la neurotecnología aplicada en

educación es un recurso prometedor potenciando la atención, el compromiso y la

dinámica de colaboración del alumnado.

Esto supone la introducción en

una dinámica nueva de trabajo que requiere formación. En esta línea, Bergaliev

y Mazurov (2020) realizaron un marco de ejecución para formar e introducir al

alumnado de primaria en el uso y dominio de nuevos tipos de productos de alta

tecnología como proyecto de viabilidad para la aceptación de este tipo de

herramientas en las normativas y legislaciones en el contexto ruso. La aparición

de materiales tan novedosos requiere de la evaluación del impacto y

consideraciones por parte de la comunidad educativa. En esta línea, Van

Atteveldt et al. (2019) arrojaron luz a esta cuestión con un diseño cualitativo

de estudio de casos recogiendo las impresiones de familias, docente e

investigadores sobre la investigación de las dimensiones del marco RRI

(Reglamento del Régimen Interno de los centros), considerando la escuela un

agente anticipador a posibles impactos de cambios e innovaciones sociales.

La neurotecnología demuestra

ser una herramienta útil dentro de la educación, tanto para la mejora y apoyo,

como es el caso de las personas en neurorehabilitación, pudiendo ser un recurso

viable en la modulación del aprendizaje y conducta de sujetos con lesiones

neurológicas mejorando el aprendizaje comprensivo y el proceso de “no

recuperación” (Putrino et al. 2022), o por otro lado en el contexto de las

NEAE, Pease et al. (2021) desarrollaron un protocolo con herramientas

neurotecnológicas para la mejora de las deficiencias visuales esperando

resultados positivos en el rendimiento de alumnado con deficiencia visual y

ratificando la necesidad de colaboración a nivel clínico y educativo para la

implementación exitosa.

No solo como una herramienta

de mejora si no de potenciación y preparación del aprendizaje, Wang et al.

(2019), construyeron un casco de señales eléctricas de neuronas para registrar

la capacidad de concentración del alumnado procesándose en un interfaz

interactivo de naves espaciales, en el que a más concentración más avance de la

nave siendo un preámbulo positivo de motivación al aprendizaje y habilidades

científicas. En consonancia, se sitúan las evidencias recogidas por Requejo

& Ramajo (2022), quiénes abogan por el impacto de la práctica musical o el

desarrollo de habilidades musicales como un elemento potenciador de la

neuroplasticidad, aumentando la actividad neuronal y generando efectos

positivos en los procesos neuropsicológicos y las habilidades académicas de

niños y niñas músicos.

Las intervenciones

neurotecnologicas ponen sobre la balanza las potencialidades de su uso, en

diversos contextos. Rapson et al. (2022) plantean en el contexto

fisioterapéutico un protocolo de actuación en ECA (Ensayo controlado aleatorio)

sobre alumnado con parálisis cerebral siendo una herramienta idónea de

intervención, viable y factible. De forma particular, Guven et al. (2021)

generan un programa dedicado a jóvenes con epilepsia y a sus familias,

mejorando y evaluando a partir de una Web WEEP, los conocimientos,

auto-eficiencia anticonvulsiva, actitud y alfabetización en cibersalud. No solo

es un marco de actuación e intervención si no una herramienta de asistencia

para la mejora de habilidades. Ejemplo de ello es el estudio de Thumbeck et al.

(2021), quiénes analizaron las estrategias

neurotecnológicas usadas en PWA (Personas con afasia) para evaluar las mejoras en

comprensión lectora y actividades de lectura mediante diseño pre-test y post-test, registrando

considerables mejoras significativas.

Se puede observar que la

neurotecnología es garantía, en la mayoría de ocasiones, de resultados

positivos, pero además puede llegar a ser una propia fuente de feedback en

procesos educativos. Sorochinski et al. (2022) presentaron el neuro-feedback

dentro del proceso de aprendizaje para potenciar la capacidad de vigilar la

atención mejorando así la adquisición de la información y la concentración,

obteniendo resultados significativamente positivos, o por otra parte Pillete et

al. (2020) que propusieron un Interfaz Cerebro-Ordenador que con bases en la

imaginación mental, reflejaban mediante frases y combinaciones de expresiones

faciales un feedback en los procesos de mejora de la comunicación consiguiendo

mejoras en la predisposición para el trabajo en grupo o en la capacidad de

aprender y memorizar.

Tabla 2

Caracterización de los artículos incluidos

|

Autor

y año

|

Objetivo del estudio

|

Participantes

|

Muestra

|

Diseño

|

Resultados

|

|

Martín-Requejo &

Santiago-Ramajo (2022)

|

Evaluar el impacto de la educación musical en procesos neuropsicológicos

y en habilidades académicas de los niños.

|

E

|

-

|

T

|

La práctica musical prolongada da lugar a una mayor neuroplasticidad,

aumento de la actividad neuronal en el temporal superior derecho, mejoras en

inhibición. También se registran mejoras en la memoria de trabajo, en la

percepción y procesamiento neural del habla… El ser músico posee un impacto

positivo en los procesos neuropsicológicas y en las habilidades académicas.

|

|

Pease et al. (2021)

|

Describir el protocolo para una evaluación de la viabilidad del proceso

de exploración del uso de herramientas neurológicas para la mejora de las

deficiencias visuales en contextos educativos.

|

E con NEAE, P

|

-

|

T

|

El protocolo desarrollado es viable y factible para mejorar las

habilidades y el rendimiento de alumnado con discapacidad visual. Es

necesaria una colaboración estrecha entre el área clínica y educativa para su

implementación y éxito.

|

|

Rapson et al. (2022)

|

Elaborar un protocolo de evaluación de factibilidad de un ECA (Ensayo

controlado aleatorio) en una intervención fisioterapéutica.

|

E con parálisis

cerebral

|

40

|

Cuan

|

El protocolo desarrollado es viable y factible para evaluar la

intervención fisioterapéutica en jóvenes con parálisis cerebral, determinando

la idoneidad del ECA y la aceptación de la intervención.

|

|

Thumbeck et al. (2021)

|

Analizar una intervención basada en estrategias sobre la comprensión

sobre la comprensión lectora a nivel de texto y sobre las actividades de

lectura en las PWA.

|

E con afasia

|

24

|

Cuan

|

El protocolo desarrollado espera mejoras significativas en la comprensión

lectora partiendo de la comparación de los datos primarios y secundarios del pre test y post test.

|

|

Guven et al. (2021)

|

Desarrollar un programa de educación sobre la epilepsia para evaluar los

conocimientos, la autoeficiencia, la actitud y la

alfabetización en salud electrónica de jóvenes con epilepsia y sus familias.

|

E, P

|

28

|

Cuan.

|

Los resultados determinaron que las puntuaciones medias de conocimientos,

autoeficiencia anticonvulsiva, actitud y

alfabetización en cibersalud habían aumentado signifiaivamente tras el WEEP. Además de un aumento en

las puntuaciones de conocimientos, ansiedad, autogestión y alfabetización

entre los padres del grupo de intervención.

|

|

Putrino et al. (2022)

|

Evaluar la reducción del deterioro del sistema motor en la

neurorrehabilitación en distintas perspectivas (neuro-ingeniería…)

|

E

|

-

|

T

|

Se concluye que la tecnología en neurorrehabilitación puede usarse para

alcanzar objetivos en personas con lesiones siendo herramienta para modular

aprendizaje y conducta. Implica que el objetivo implícitamente es mejorar el

aprendizaje compensativo y no la recuperación.

|

|

Van Atteveldt et al.

(2019)

|

Descubrir qué consideraciones surgen desde la perspectiva de los

adolescentes, padres y profesores investigadores con respecto a las

dimensiones del marco de la RRI.

|

E, P, D

|

P= 6

D= 8

E= 6

|

Cual

|

El estudio descubre que el uso de RRI la sociedad se anticipa a los diferentes

impactos potenciales de la intervención basada en neuro-tecnología y permite

a los investigadores adaptar la intervención de acuerdo con las perspectivas

de anticipación sociales.

|

|

Privitera y Du (2022)

|

Diseño de protocolo de actuación con las herramientas de innovación

dentro de la neurotecnología.

|

-

|

-

|

T

|

Se concluye que la neurotecnología aplicada a

la educación es prometedora teniendo en cuenta la identificación de neuromarcadores en la atención, el compromiso y la

dinámica de colaboración. Afirma también la necesidad de desarrollar recursos

y herramientas que permitan un uso adecuado de la neurotecnología.

|

|

Wang et al. (2019)

|

Preparación del alumnado para un aprendizaje óptimo, mediante un casco

que mide las señales eléctricas de las neuronas del cerebro, un juego de

competición representadas en cohetes medir la concentración del alumnado.

|

E

|

-

|

Cuan

|

Los datos pretenden ser una ayuda para gobiernos y legislaciones pretendiendo

ser un apoyo para la toma de decisiones científicas, mejorando la tecnología

y calidad de los recursos.

|

|

Pillete et al. (2020)

|

Diseño, implementación y evaluación de una Interfaz Cerebro-Ordenador

basada en la Imaginación Mental, (MI-BCI), en función del rendimiento y el

progreso del alumnado, combinan frases y expresiones faciales.

|

E con necesidades comunicativas o rehabilitantes

de ictus.

|

104

|

Cuan

|

Se descubre que las personas no autónomas están predispuestas a trabajar

en grupo con dicha interfaz, siendo favorecidas en comparación con personas

autónomas. Se registran mejoras en la capacidad de aprender y memorizar.

|

|

Sorochinski et al. (2022)

|

Uso del neuro feedback en el proceso de

aprendizaje de los materiales educativos en vídeo. Teniendo como hipótesis:

Capacidad del alumnado para vigilar su atención contribuyendo a la mejora de

la adquisición de información y concentración.

|

E

|

20

|

Cuan

|

Los sujetos obtuvieron resultados significativamente mejores en la escala

de atención con el neuro feedback, teniendo en

cuenta los resultados de grupo focal y grupo de control.

|

|

Bergaliev y Mazurov (2020)

|

Diseño de marco de ejecución para el desarrollo y dominio de nuevos tipos

de productos de alta tecnología (NeuroNet STI)

pretendiendo desarrollar neuro-tecnologías aprobadas por el Consejo

Presidencial de Economía y Desarrollo Innovador de Rusia.

|

E

|

-

|

T

|

Mediante los resultados de la aplicación de neuro-tecnologías en el entorno

social, se aportó una ecuación de regresión lineal que correlacionaba la

dependencia del alumnado implicado en trabajos, la cantidad de fondos y el

número de actos realizas para familiarizarse con los recursos.

|

4. Discusión y conclusiones

La presente revisión tenía el

objetivo de realizar una panorámica de las investigaciones realizadas sobre el

uso de la neurotecnología con fines docentes desde una perspectiva ética. Tras

un arduo proceso de búsqueda en diferentes bases de datos, el proceso de

revisión realizado reportó 12 artículos que se ajustaban a los parámetros

establecidos. A continuación, se trata de dar respuesta las cuatro preguntas de

investigación que motivaron este trabajo de revisión.

4.1.

¿Qué intervenciones basadas en neurotecnología se han

desarrollado en las diferentes etapas educativas?

La presente investigación no

aporta evidencias sobre distintas etapas educativas, salvo dos estudios

situados en educación primaria (Bergaliev & Mazurov, 2020; Wang et al.,

2019). Por el contrario, han aunado esfuerzos en torno a mejorar diferentes

ámbitos de desarrollo y aprendizajes instrumentales con estudiantes con

necesidades educativas especiales (Guven et al., 2021; Rapson et al., 2022;

Thumbeck et al., 2021), especialmente aquellos con diversidad sensorial o

cognitiva. Estos hallazgos implican que la inclusión de la neurotecnología con

un prisma educativo va en paralelo a las intervenciones educativas diseñadas e

implementadas desde las instituciones educativas, actuando como complemento de

las mismas (Antonenko, 2019). En esta línea, considerando que se trata de un

aliciente potenciador de aprendizaje (Requejo & Ramajo, 2022) y atendiendo

a las teorías cognitivas y de desarrollo sobre la tecnología educativa

(Rudolph, 2017), tiene especial cabida en las etapas de educación primaria y

secundaria. Sin embargo, si se considera diferentes grados de afección dentro

del colectivo de necesidades educativas especiales, la neurotecnología puede

implementarse también en otros estadíos educativos y en modalidades de la

Educación no Formal. En cualquier caso, estudios como el desarrollado por

Demera-Zambrano et al. (2021) mostraron el potencial que la neurotecnología

ofrece para la atención del colectivo con necesidades educativas especiales

desde la mirada de cincuenta docentes en ejercicio, pues permiten un mayor

entendimiento de éstos hacia cómo aprenden sus estudiantes, así como la amplia

variedad de ritmos y capacidades que poseen.

4.2.

¿Sobre qué temáticas versan las intervenciones basadas en neurotecnología

realizadas?

Los estudios incluidos en la

revisión son variados en cuanto a las temáticas desarrolladas. De esta manera,

se encuentran investigaciones orientadas a mejorar las habilidades

lectoescritoras y de comprensión del alumnado (Thumbeck et al., 2021), la

comunicación (Pillete et al., 2022), la memoria y la cognición (Sorochinski et

al., 2022), la atención (Wang et al., 2019), la motivación e incluso,

fortalecen aspectos más sociales como la colaboración (Privitera &Du,

2021). El carácter interdisciplinar que caracteriza esta tecnología conlleva la

no encuadración en ninguna área de conocimiento concreta. De esta manera, una

visión cohesionada donde se alternan los procesos instruccionales típicos pertenecientes

a las diferentes áreas de conocimiento de forma complementaria a intervenciones

de este tipo, podría ser el éxito para lograr la plena inclusión y desarrollo

integral de todo el alumnado.

4.3.

¿Qué riesgos éticos tiene el uso de la neurotecnología

educativa tiene para el alumnado?

Todas las investigaciones

incluidas en la revisión han señalado en mayor o menor medida que el uso de la

neurotecnología puede suponer un riesgo personal para los estudiantes, al poder

vulnerar su intimidad, privacidad y derecho hacia la intimidad e incluso correr

el riesgo a la exclusión. En esta línea, conocer el funcionamiento del cerebro

del estudiante, conociendo su capacidad y estilo de aprendizaje, utilizando medidas

fisiológicas puede conllevar un “etiquetaje” en un alumnado ya diverso de por

sí, que puede desencadenar en medidas discriminatorias no intencionales.

Asimismo, la neuroética aboga por una consideración holística de la persona,

donde no solo se atienda a los datos objetivos aportados por la aparotología

utilizada ya sea con fines docentes o clínicos, considerando como prioridad la

consideración del contexto donde la persona se desenvuelve (Shook et al.,

2014).

4.4.

¿Cuáles son los beneficios e inconvenientes que tiene la neurotecnología

para el aprendizaje del alumnado?

Pese a la escasa evidencia

empírica encontrada, el uso de la neurotecnología posee un elevado número de

beneficios en el alumnado. En primer lugar, se adhiere a la tendencia de

desarrollar procesos de aprendizaje individualizados y ajustados a las

características del estudiantado (Kuch et al., 2020). A su vez, debido a la

plasticidad del cerebro, la vía para incorporar la neuotecnología en la

educación tendrá que pasar por su potencial para la estimulación cerebral

(Williamson, 2019), propiciando la construcción de sinapsis neuronales,

especialmente en aquellos estudiantes con diversidad funcional o deterioro

cognitivo (Guven et al., 2021; Rapson et al., 2022; Pillete et al., 2022; Thumbeck

et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019). Sin embargo, también persisten ciertos

desafíos que pueden entorpecer el potencial que la neurotecnología puede

ofrecer en el campo de la educación. En primer lugar, ha de destacarse la

formación docente. A pesar de existir grandes avances en torno a la

profesionalización docente en términos de alfabetización digital

(Fernández-Batanero et al., 2020), aún persisten grandes carencias formativas y

actitudes poco proactivas para su implementación. Si bien es cierto que la prevalencia

de cierto malestar o miedo hacia lo novedoso o desconocido puede producir

ciertas reticencias en unos docentes cuyas funciones se han multiplicado en los

últimos años, lo que debe primar es el bienestar integral del estudiantado. En

segundo lugar, no debe omitirse el elevado coste que supone el uso de esta

aparatología, por lo que no todas las instituciones educativas pueden

permitírselo. Esta cuestión abre el debate sobre la necesidad de invertir en

educación por parte de las políticas nacionales y supranacionales, con vistas a

equipar con los recursos y tecnologías necesarias para diseñar, desarrollar e

implementar procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje de calidad que favorezcan la

equidad de todo el alumnado, especialmente de aquellos más vulnerables.

En cualquier caso, la revisión

sistemática orienta el estado de la cuestión sobre la integración de la

neurotecnología en el campo de la educación. Desafortunadamente, este tópico

está en consonancia con lo tendencia de los avances en educación. Muchas de las

incorporaciones que se suceden en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje y en

la realidad de las aulas provienen de otras áreas de conocimiento. Este hito

entorpece y/o ralentiza su inclusión plena, sobre todo, en los primeros

estadios. Si bien es cierto que la neurotecnología puede convertirse en un

importante aliado en el diseño de una respuesta educativa eficaz, se requiere

de tiempo y esfuerzo para capacitar a los profesionales de la educación que

deben liderar tales iniciativas. Asimismo, la falta de evidencia empírica, pese

a existir un importante corpus de estudios de carácter teórico impide

extrapolar los beneficios reales que la neurotecnología puede ofrecer a

diferentes áreas de conocimiento impartidas por las instituciones educativas. En

esta línea, avanzar en esta línea y contribuir a la emergencia de

investigaciones empíricas en diferentes materias y en diferentes etapas podría

contribuir a delimitar claves de éxito para el desarrollo de buenas prácticas

educativas. Al mismo tiempo, a partir de los resultados obtenidos se ha

encontrado el enorme potencial que la neurotecnología puede ofrecer para el

campo de la Educación Especial, por lo que la proliferación de estudios basados

en intervenciones educativas que utilicen la neurotecnología con diferentes

colectivos con necesidades específicas de apoyo educativo, podría también

contribuir plenamente a mejorar en este campo.

5. Financiación

Esta publicación forma parte

del Proyecto de I+D+i, PID2019-108230RB-I00, financiado por MCIN/ AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

References

Antonenko, P. D. (2019). Educational neuroscience:

Exploring cognitive processes that underlie learning. Mind, brain and technology, 27-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02631-8_3

Ardila, A., Bertolucci, P. H.,

Braga, L. W., Castro-Caldas, A., Judd, T., Kosmidis, M. H., ... & Rosselli,

M. (2010). Illiteracy: the neuropsychology of cognition without reading. Archives

of clinical neuropsychology, 25(8), 689-712. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acq079

Aguiton, S. (2015). Mettre en démocratie les technologies émergentes ?

Participation et pouvoir à l’ère de la crise écologique. Contretemps, 26,

40-49. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02009585

Bastidas, V. (2021) Neurotecnología:

interfaz cerebrocomputador y protección de datos

cerebrales o neurodatos en el contexto del

tratamiento de datos personales en la unión europea. Revista iberoamericana

de derecho informático, 101-176.

Bergaliev, T., & Mazurov, M. (2020). Study of the Effectiveness of State

Support in the Development and Implementation of Neuro-educational

Technologies. In International Conference of Artificial Intelligence,

Medical Engineering, Education (pp. 315-321). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39162-1_29

Cox, A. M. (2021). Exploring

the impact of Artificial Intelligence and robots on higher education through

literature-based design fictions. International Journal of Educational

Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00237-8

Dehaene, S. (2007). Les neurones

de la lecture. Odile Jacob.

Demera-Zambrano, K. C., LópezVera,

L. S., Zambrano-Romero, M. G., Navarrete Solórzano, D. A., Quijije

Troya, N. S., & Rodríguez Gámez, M. (2021). Educational neurotechnology in

attention to the specific needs of higher basic general education students. PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of

Egypt/Egyptology, 18(10), 943-957.

Fanelli, A., & Ghezzi D. (2021).

Transient electronics: new opportunities for implantable Neurotechnology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 72,22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2021.08.011

Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M.,

Fernández-Cerero, J., & García-Martínez, I. (2020). Digital competences for

teacher professional development. Systematic review. European Journal of

Teacher Education, 45(4), 513-531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1827389

Güven, Ş. T., Dalgiç, A. İ., & Duman, Ö. (2020). Evaluation of

the efficiency of the web-based epilepsy education program (WEEP) for youth

with epilepsy and parents: A randomized controlled trial. Epilepsy &

Behavior, 111, 107142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107142

Ienca, M., & Andorno, R. (2017). Towards new human rights in the age of

neuroscience and neurotechnology. Life Sci Soc Policy 13, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40504-017-0050-1

Johnson, Z. A., Sciolino, N.

R., Plummer, N. W., Harrison, P. R., Jensen, P., & Robertson, S. D. (2021).

Assessment of mapping the brain, a novel research and

neurotechnology based approach for the modern neuroscience classroom. Journal

of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education, 19(2), A226.

Kuch, D., Kearnes, M., &

Gulson, K. (2020). The promise of precision: datafication in medicine, agriculture and education. Policy Studies, 41(5), 527-546.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2020.1724384

Martin-Requejo, K., &

Santiago-Ramajo, S. (2022). Últimos avances científicos de los efectos neuropsicológicos

de la educación musical. Artseduca, (31), 275-286. https://doi.org/10.6035/artseduca.5976

Matusz, P. J., Dikker, S.,

Huth, A. G., & Perrodin, C. (2019). Are we ready for real-world

neuroscience? Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 31(3), 327-338. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_e_01276

Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo

Económicos [OCDE] (2022). Recommendation of the

Council on Responsible Innovation in Neurotechnology, OECD/LEGAL/0457

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E.,

Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow,

C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía

actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española

de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Pease, A., Goodenough, T., Sinai,

P., Breheny, K., Watanabe, R., & Williams, C.

(2021). Improving outcomes for primary school children at risk

of cerebral visual impairments (the CVI project): study protocol for the

process evaluation of a feasibility cluster-randomised

controlled trial. BMJ open, 11(5), e044856. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044856

Pillette, L., Jeunet, C., Mansencal, B., N’kambou, R., N’Kaoua, B., & Lotte, F. (2020). A physical learning

companion for Mental-Imagery BCI User Training. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 136, 102380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2019.102380

Pradas, S. (2017). La Neurotecnología

Educativa. Claves del uso de la tecnología en el proceso de aprendizaje. ReiDoCrea, 6(2), 40-47.

Pradas, S. (2016). Neurotecnología

educativa. La tecnología al servicio del alumno y del profesor. Centro Nacional

de Innovación e Investigación Educativa. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y

Deporte.

Privitera, A. J., & Hao,

D. (2022). Educational neurotechnology: Where do we go from here? Trends in

Neuroscience and Education, 19, 100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2022.100195

Putrino, D., & Krakauer, J. W. (2022). Neurotechnology’s Prospects

for Bringing About Meaningful Reductions in Neurological Impairment. Neurorehabilitation

and Neural Repair, 15459683221137341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968322113734

Rapson, R., Marsden, J.,

Latour, J., Ingram, W., Stevens, K. N., Cocking, L., & Carter, B. (2022). Multicentre, randomised

controlled feasibility study to compare a 10-week physiotherapy programme using an interactive exercise training device to

improve walking and balance, to usual care of children with cerebral palsy aged

4–18 years: the ACCEPT study protocol. BMJ open, 12(5), e058916. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058916

Raza, S. A., & Khan, K. A. (2021). Knowledge and innovative

factors: how cloud computing improves students’ academic performance. Interactive

Technology and Smart Education, 19(2), 161-183. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-04-2020-0047

Reber, P. J. (2013). The

neural basis of implicit learning and memory: A review of neuropsychological

and neuroimaging research. Neuropsychologia,

51(10), 2026-2042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.06.019

Roebuck-Spencer, T. M., Glen,

T., Puente, A. E., Denney, R. L., Ruff, R. M., Hostetter, G., & Bianchini,

K. J. (2017). Cognitive screening tests versus comprehensive neuropsychological

test batteries: a national academy of neuropsychology education paper. Archives

of Clinical Neuropsychology, 32(4), 491-498. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx021

Rodríguez Garza, R. (2016). La construcción de ambientes de aprendizajes desde los

principios de la neurociencia cognitiva. Revista de educación

inclusiva, 9(2), 245-263.

Rudolph, M. (2017). Cognitive

theory of multimedia learning. Journal of Online Higher Education, 1(2),

1-10.

Shook, J. R., Galvagni, L., &

Giordano, J. (2014). Cognitive enhancement kept within contexts: neuroethics and informed public policy. Frontiers in

systems neuroscience, 8, 228. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00228

Sorochinsky, M., Koryakin, P., &

Popov, M. (2022, September). A study of students' attention levels while