Percepciones de los futuros docentes

sobre la integración de la robótica creativa en Educación Primaria

Perceptions of future teachers on the inclusion of creative

robotics in Primary Education

Dra. Pilar Manuela

Soto-Solier. Profesora Contratada Doctora. Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de

Granada, España

Dra. Pilar Manuela

Soto-Solier. Profesora Contratada Doctora. Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de

Granada, España

Dña. Verónica

Villena-Soto. Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación.

Universidad de Granada, España

Dña. Verónica

Villena-Soto. Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación.

Universidad de Granada, España

Dr. David

Molina-Muñoz. Profesor Contratado Doctor. Facultad de

Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Granada, España

Dr. David

Molina-Muñoz. Profesor Contratado Doctor. Facultad de

Ciencias de la Educación. Universidad de Granada, España

Recibido:

2022/10/14; Revisado: 2022/11/01; Aceptado:2023/04/02; Preprint: 2023/04/17; Publicado: 2023/05/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Soto-Solier,

P. M., Villena-Soto, V., Molina-Muñoz, D. (2023). Percepciones de los futuros

docentes sobre la integración de la robótica creativa en Educación Primaria [Perceptions of future teachers on the

inclusion of creative robotics in Primary Education]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de

Medios y Educación, 67, 284-314. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.96781

RESUMEN

En una sociedad cambiante y compleja como la actual,

el desarrollo del pensamiento creativo resulta fundamental para la resolución

de problemas y la toma de decisiones. Por ello, las metodologías STEAM están

cada vez más presentes en las aulas con el propósito de fomentar la creatividad

de los estudiantes a través, entre otras herramientas, de la robótica creativa.

En este contexto, esta investigación tiene por objeto conocer las percepciones

de maestros de Educación Primaria en formación sobre la inclusión de la

robótica educativa en esta etapa educativa, sus pros y sus contras. El estudio,

de carácter descriptivo-inferencial, usa una muestra de conveniencia de 121

estudiantes del Grado en Educación Primaria de la Universidad de Granada. Para

la recogida de los datos se utilizó una versión adaptada de un cuestionario

previamente validado. Los resultados de la muestra en su conjunto reflejan

valoraciones favorables con respecto a la introducción de la robótica educativa

en la etapa de Educación Primaria. Por género, destaca la valoración más

positiva de las chicas con respecto la de los chivos atendiendo a los

beneficios de la introducción de la robótica en el currículo. Nuestros

resultados coinciden con los de la mayoría de estudios previos acerca del tema.

ABSTRACT

In today's changing and complex

society, the development of creative thinking is essential for problem solving

and decision making. For this reason, STEAM methodologies are increasingly

present in the classroom with the aim of fostering students' creativity

through, among other tools, creative robotics. In this context, this research

aims to find out the perceptions of Primary School teachers in training about

the inclusion of educational robotics in this educational stage, its pros and

cons. The study, of a descriptive-inferential nature, uses a convenience sample

of 121 students of the Degree in Primary Education at the University of

Granada. An adapted version of a previously validated questionnaire was used to

collect the data. The results of the sample as a whole show favourable

evaluations with respect to the introduction of educational robotics in the

Primary Education stage. By gender, the more positive assessment of girls

compared to boys stands out in terms of the benefits of the introduction of

robotics in the curriculum. Our results coincide with those of most previous

studies on the subject.

PALABRAS CLAVES· KEYWORDS

enseñanza primaria; formación de maestros de primaria;

percepciones; robótica; STEAM.

primary education; primary school teacher training;

perceptions; robotics; STEAM.

1. Introducción

Las orientaciones del

Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, recogidas en la Agenda Estratégica de

Innovación del Instituto Europeo de Innovación y Tecnología para 2021/2027,

sugieren una formación en competencias clave por parte de los ciudadanos para

poder alcanzar el desarrollo personal, profesional y social que demanda el

mundo globalizado, un desarrollo holístico vinculado al conocimiento. La

complejidad de los problemas de la sociedad actual requiere que esta formación

contemple no solo contenidos conceptuales o procedimentales, sino también otras

habilidades como la creatividad (Beghetto y Kaufman,

2013). Hoy en día, la creatividad desempeña un papel fundamental desde un doble

punto de vista: por un lado, a nivel individual, como refuerzo de la habilidad

de cada persona para adaptarse a situaciones nuevas y, por otro, a nivel

colectivo, como un mecanismo básico para el desarrollo social, científico y

tecnológico (Elgrably y Leikin,

2021).

La irrupción de la

creatividad entre las necesidades formativas del alumnado ha provocado cambios

importantes dentro del panorama educativo. Uno de ellos hace referencia a la

inclusión en las metodologías STEM (siglas de Science,

Technology, Engineering y Mathematics), inicialmente centradas en la enseñanza

interdisciplinar de materias de carácter científico y tecnológico, de aspectos

relacionados con los ámbitos artístico y humanístico. En efecto, en el mundo

actual, las prácticas de enseñanza de las disciplinas científicas y tecnológicas

no pueden separarse del pensamiento creativo, el diseño, la comunicación y las

habilidades artísticas. Esto ha propiciado la incorporación de la “A” de Arte,

a las metodologías STEM, dando lugar a las metodologías STEAM (Yakman y Lee, 2012). Las metodologías STEAM constituyen un

enfoque de enseñanza-aprendizaje que mantiene el carácter interdisciplinar de

STEM, pero incluyendo la disciplina artística y la creatividad (Clapp y Jiménez, 2016; Conradty y

Bogner, 2020; Guyotte et

al., 2015; Runco y Acar,

2012; Zawieska y Duffy, 2015) con el objeto de dar

respuesta a problemas reales a través de un método construccionista que

involucra “aprender haciendo” (Papert, 1980; Zamorano-Escalona et al, 2018).

Dado que la creatividad (Runco y Acar, 2012) está

implícita en las artes y la tecnología (Kaufman et al. 2009), la educación

STEAM es crucial para promover la innovación y el cambio adaptativo. Es

significativa para el desarrollo, no solo educativo, sino también económico y

sostenible de la sociedad. Taylor et al. (2017) resaltan la importancia de

implementar metodologías STEAM en el aula desde edades tempranas ya que estas

proporcionan herramientas conceptuales, procedimentales y actitudinales al

alumnado que les permiten proporcionar respuestas interdisciplinares adecuadas

a problemas de la vida real (Domènech-Casal, 2018; Martín Páez et al., 2019).

De todas las estrategias

para la implementación de las metodologías STEAM, aquellas que incorporan la

robótica educativa han mostrado importantes beneficios en diversos aspectos

relacionados con el aprendizaje de estudiantes en diversas áreas como la de

matemáticas, física e ingeniería (Benitti, 2012),

pero también en áreas de humanidades, arte y ciencias sociales (Casado

Fernández, et al., 2020; Leoste et al., 2021).

En efecto, la aplicación de

la robótica en el aula se traduce en mejoras significativas en habilidades como

la resolución de problemas, las destrezas sociales, el razonamiento y el

pensamiento crítico (Benitti, 2012; Ganesh et al., 2010; Menekse et

al., 2017), las destrezas gráficas (Mitnik et al.,

2009) y la comprensión de conceptos abstractos (Williams et al., 2011). De

igual modo, se ha probado el notable impacto que tiene la robótica en el

desarrollo personal del alumnado así como en el

fomento de sus habilidades de investigación y de su pensamiento creativo (Badeleh, 2019; Baek, 2016; Burhans y Dantu, 2017; Thuneberg et al., 2018; Wannapiroon

y Petsangsri, 2020). La promoción de la creatividad

se aborda, por ejemplo, a través de la programación y de la construcción y

manipulación de software y hardware (Badeleh, 2019; Baek, 2016; Caballero-González y García-Valcárcel, 2020;

Cabello-Ochoa y Carrera-Farrán, 2017; Kahn et al., 2016; Zawieska

y Duffy, 2015), estimulando la capacidad de los estudiantes para aprender a

través de experiencias de su entorno y transferir el conocimiento dando

respuestas a los problemas de forma novedosa. Las investigaciones demuestran la

efectividad de estas experiencias cotidianas para promover el desarrollo de la

creatividad y de la innovación (Nemiro et al., 2017).

Queda demostrado, por tanto, que los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje basados

en robótica mejoran la creatividad de forma eficaz, así como todos los

componentes de esta: originalidad, elaboración, flexibilidad y fluidez.

La literatura consultada

muestra, principalmente, indagaciones acerca del efecto de la robótica en

entornos escolares de Educación Primaria y Secundaria (hasta el nivel K12) (Bers y Urrea, 2000; Dias et al.,

2005; Resnick, 1993), en escuelas técnicas y vocacionales (Alimisis

et al, 2005) así como en programas extraescolares (Barker y Ansorge,

2007; Rusk et al., 2008). Atendiendo al nivel

educativo, encontramos investigaciones que exploran el impacto de la

utilización de los kit

de robótica en el desarrollo de las habilidades y actitudes del alumnado desde

Educación Infantil a Primaria, para lo que proponen la aplicación de un marco

tecnológico, social y cultural (Jung y Won, 2018). Otras se centran en aspectos

concretos de la robótica, como la programación creativa y el pensamiento

computacional en Educación Primaria (Bers et al.,

2019; González-González, 2019; Maya et al., 2015; Moreno et al., 2019;

Sáez-López et al., 2021; Vivas-Fernández y Sáez-López, 2019), destacando los

resultados positivos y la mejora de las habilidades digitales y tecnológicas en

los estudiantes que utilizan la robótica educativa durante la etapa de Primaria

y Secundaria (Lin et al., 2005; Relkin et al., 2020;

Xia y Zhong, 2018).

A pesar de sus beneficios,

la implementación de la robótica creativa, en particular, y de las metodologías

STEAM, en general, en el aula plantea una serie de retos que provocan ciertas

reticencias entre los docentes a la hora de su aplicación. Esto se debe,

posiblemente, al desconocimiento del significado de las metodologías STEAM y su

potencial pedagógico atendiendo a la diversidad de lenguajes, conceptos o

expresiones personales y de significado (Chen y Huang, 2020; Herro y Quigley, 2017; Yakman, 2008). En efecto, la implementación de las

metodologías STEAM supone una serie de cambios con respecto a las metodologías

tradicionales, los cuales afectan de forma directa al transcurso diario de la

docencia en las aulas. Los docentes, como principales obradores de estos

cambios, tienen un papel fundamental en esta nueva realidad educativa, lo que

pone de manifiesto la necesidad de una formación docente actualizada que en

este momento se encuentra en proceso de concreción, tanto de contenido como de

estrategias y recursos, para ser implementada en el aula (Grover y Pea, 2013).

En este nuevo panorama

educativo, también se incluye, dentro de las competencias que debe de adquirir

el alumnado, el desarrollo de actitudes que fomenten la igualdad de género y

las conductas no sexistas, incidiendo en las profesiones relacionadas con la

ciencia y la tecnología desde una perspectiva de género. Este aspecto es

especialmente relevante en las áreas que abarcan las metodologías STEAM, en

donde la presencia y la participación femenina son muy bajas en comparación con

la de los hombres (Astegiano et al., 2019; Chiu, et al., 2018; García-Holgado et al., 2019;

García-Holgado et al., 2020). Son significativos los datos que muestran las

investigaciones de Cimpian et al. (2020), los cuales

indican que, a partir de los seis años, las niñas se sienten en inferioridad de

capacidades para resolver problemas basados en metodologías STEAM en relación

con los niños. Otros datos que nos hacen reflexionar sobre la brecha de género

en vocaciones científicas y tecnológicas son los que recogen informes como Descifrar el código (UNESCO, 2019), The ABC of Gender Equality in Education (OCDE, 2015) o Igualdad en cifras 2020 del Ministerio de Educación y Formación

Profesional. De ahí que la Comisión Europea considere una prioridad la

inclusión, la equidad y el desarrollo de vocaciones en el ámbito de las STEAM.

Un desafío que es planteado en el nuevo marco estratégico para la cooperación

europea, en el ámbito de la educación y formación en el Espacio Europeo de

Educación 2021-2030 y también en los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS)

recogidos en la Agenda 2030. Se incide en que la educación y la formación

inclusiva también implica desarrollar la sensibilidad de género en los procesos

de aprendizaje y en las instituciones educativas así

como cuestionar y disolver los estereotipos de género, sobre todo aquellos que

limitan la elección de los niños en relación con su ámbito de estudio. Entre

los proyectos dirigidos a afrontar este reto, encontramos El Plan de Acción de Educación Digital 2021-2027 y El Plan España Digital 2025 cuyos

objetivos principales son adaptar la educación a la era digital y promover la

participación de las mujeres en los estudios STEAM e implicar al sistema

educativo para activar el desarrollo de vocaciones científicas y tecnológicas

sin abandonar las artes. A nivel estatal, el Ministerio de Educación, Formación

y Empleo crea La Alianza STEAM por el

talento femenino como estrategia para reducir la brecha entre alumnas y alumnos así como Niñas

en pie de Ciencia en el que se obtienen los datos más recientes sobre este

problema, recogidos en el estudio Radiografía

de la brecha de género en la formación STEAM (2022) realizado por el

Ministerio de Educación sobre la trayectoria educativa de las niñas y de las

mujeres en España.

El presente estudio tiene

por objetivo identificar las opiniones de futuros maestros de Educación

Primaria sobre la inclusión de la robótica creativa en las aulas de Primaria,

incidiendo en las percepciones que tienen acerca de las potencialidades y

limitaciones de carácter pedagógico que conlleva la incorporación de esta

disciplina en dicha etapa educativa. En concreto, se plantean las siguientes

preguntas de investigación:

1. ¿Cuál es la opinión de los futuros maestros

acerca de la inclusión de la robótica creativa en el currículo de Educación

Primaria?

2. ¿Qué tipo de vocaciones futuras consideras

los futuros maestros que podría despertar la robótica creativa?

3. ¿Qué fortalezas y limitaciones acerca de

la inclusión de la robótica creativa en el aula perciben los futuros maestros?

4. ¿Hay diferencias en función del género en

las opiniones de los maestros sobre la inclusión de la robótica creativa en el

aula?

2. Metodología

Los participantes en el

estudio son 121 estudiantes, 74 mujeres (61,16%) y 47 hombres (38,84%), del

primer curso del grado en Educación Primaria de la Universidad de Granada,

seleccionados mediante un muestreo de voluntarios. La mayoría de ellos (80,43%)

han accedido a la titulación tras cursar el Bachillerato. Los ámbitos

académicos en los que los estudiantes consideran que han destacado a lo largo

de su trayectoria académica previa son el de la educación física (28,92%), el

de la educación en valores (21,48%), el lingüístico (17,35%), el artístico (14,87%),

el matemático (14,04%) y, en menor grado, el de conocimiento del medio social,

el de conocimiento del medio natural y el tecnológico.

Como instrumento de recogida

de datos se ha utilizado una adaptación del cuestionario diseñado por

Cabello-Ochoa y Carrera-Farrán (2017). Este

cuestionario fue creado con la finalidad recoger las actitudes y creencias de

docentes en ejercicio de Educación Primaria y de Educación Infantil sobre la

implantación de la robótica creativa en el aula. Dado que nuestro estudio se

dirige a maestros aún en la etapa de formación universitaria, fue necesaria la

modificación de algunos ítems del cuestionario original. Los cambios más

sustanciales se produjeron en las preguntas de carácter sociodemográfico, en

donde los ítems que indagaban en el bagaje profesional de los maestros en

ejercicio en el cuestionario original fueron modificados en el cuestionario

adaptado para recoger información sobre la trayectoria académica y formativa de

los estudiantes. Del mismo modo, se suprimieron los ítems que recogían el

tiempo de experiencia en la enseñanza y el nivel educativo en el que los

docentes en ejercicio desarrollaban la mayoría de su actividad profesional, por

carecer de sentido en el caso de maestros aún en formación.

El cuestionario adaptado

resultante comienza con 5 preguntas de carácter sociodemográfico a las que

siguen 20 preguntas a través de las cuales se recogen sus opiniones acerca de

la incorporación de esta materia a la enseñanza obligatoria. Respetando el

diseño del cuestionario original propuesto por los autores, se utilizó una

escala de Likert con 4 posibles opciones (nada de acuerdo, poco de acuerdo,

bastante de acuerdo, totalmente de acuerdo) para la recogida de las opiniones

de los encuestados, aunque el cuestionario también incluye algunas preguntas de

opción múltiple y respuesta única y una pregunta de respuesta abierta.

El cálculo de la fiabilidad

y la consistencia interna del cuestionario para el único constructo latente

"Percepciones de los estudiantes sobre la inclusión de la robótica

creativa educativa en Educación Primaria" se llevó a cabo utilizando el

coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. A continuación, los datos recogidos fueron

analizados, principalmente, mediante técnicas descriptivas. Tras el análisis de

los datos del conjunto de toda la muestra, se estudiaron por separado las

respuestas según el género de los encuestados. Para comprobar si las

diferencias entre las respuestas dadas por chicos y chicas diferían de manera

relevante se aplicaron contrastes de diferencias de proporciones,

considerándose significativas aquellas diferencias en las que el contraste

asociado reflejara un p-valor inferior a 0,05.

3. Análisis y resultados

El coeficiente alfa de

Cronbach arrojó un valor de 0,79, el cual, según George y Mallery

(2003), indica un nivel aceptable de fiabilidad del cuestionario, muy próximo a

un nivel bueno.

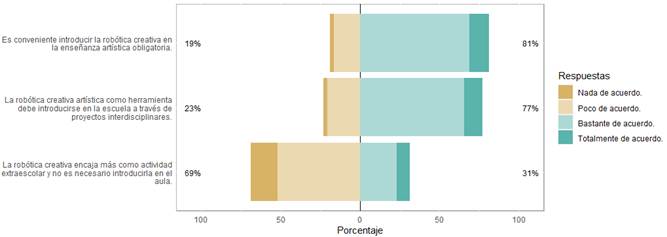

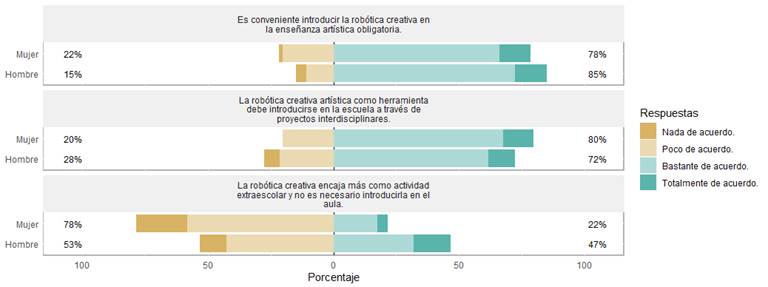

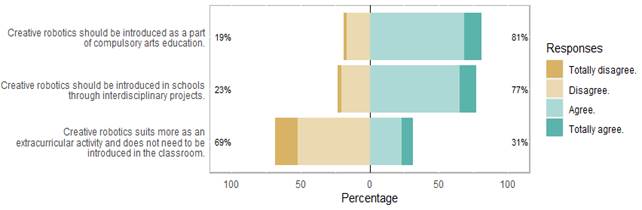

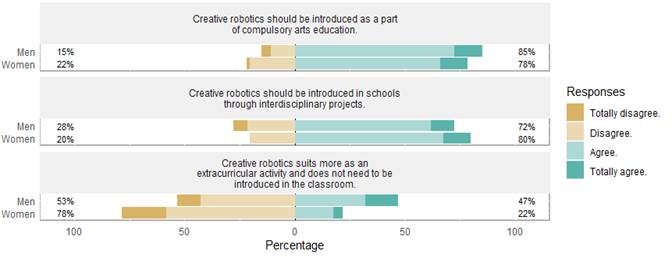

De forma global, y tal y

como refleja la Figura 1, la mayoría de los estudiantes encuestados muestran

una opinión favorable con respecto a la introducción de la robótica creativa

como parte de la educación artística en la enseñanza obligatoria. Es más, cerca

de un 70% de los participantes considera que los contenidos de robótica no

deberían tener carácter extraescolar, sino que tendrían que impartirse en el aula

como parte del currículo oficial. Por otro lado, más de tres cuartas partes de

los estudiantes consideran conveniente que la enseñanza de estos contenidos se

aborde desde una perspectiva interdisciplinar.

Figura

1

Opiniones de los alumnos encuestados con respecto

a la introducción de la robótica creativa en la educación obligatoria

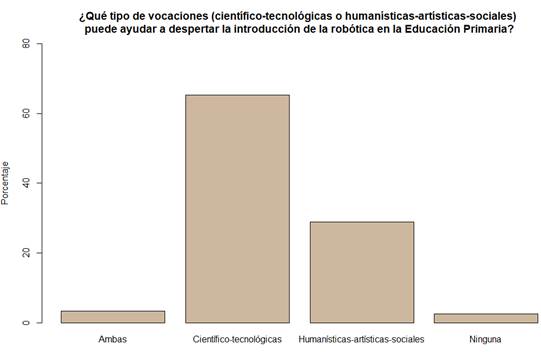

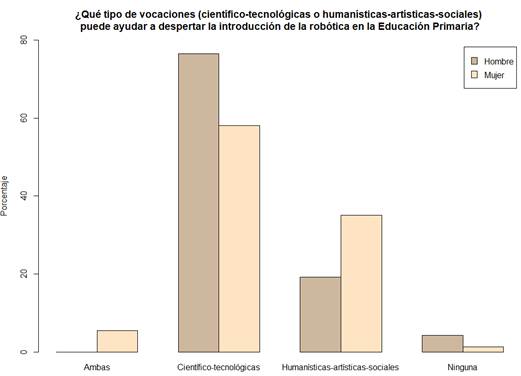

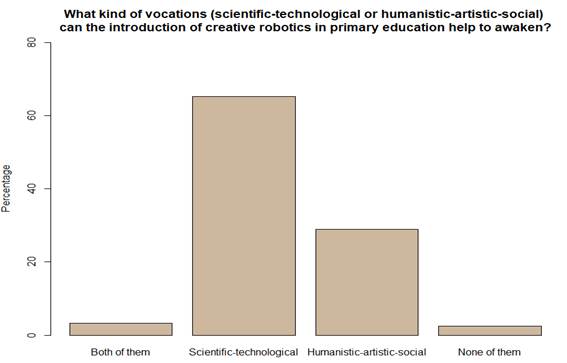

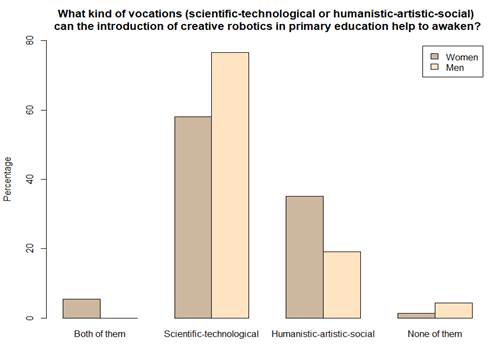

Debido, quizás, a este

carácter multidisciplinar, los encuestados tienen opiniones diversas acerca de

la tipología de las vocaciones que la robótica podría suscitar en los

estudiantes de Educación Primaria, como puede verse en la Figura 2. Para más

del 65% de los participantes estas vocaciones estarían relacionadas con el

ámbito científico-tecnológico mientras que algo menos del 30% cree que serían

de tipo humanístico-artístico-social. Solo el 3,3% de los estudiantes

consideran que podrían despertarse ambas, de forma indistinta.

Figura

2

Opiniones de los alumnos encuestados con respecto

al tipo de vocaciones que la robótica podría despertar en el alumnado.

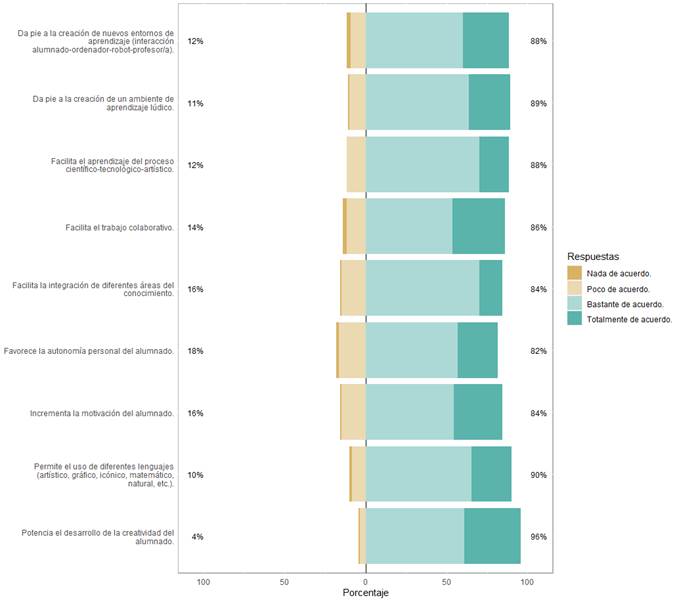

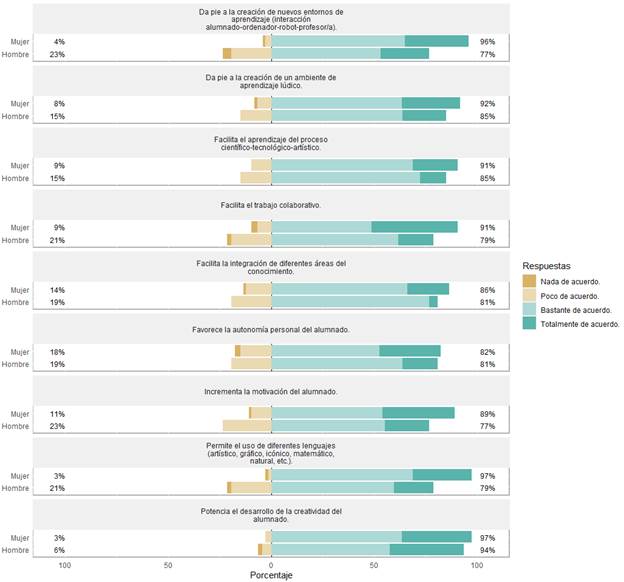

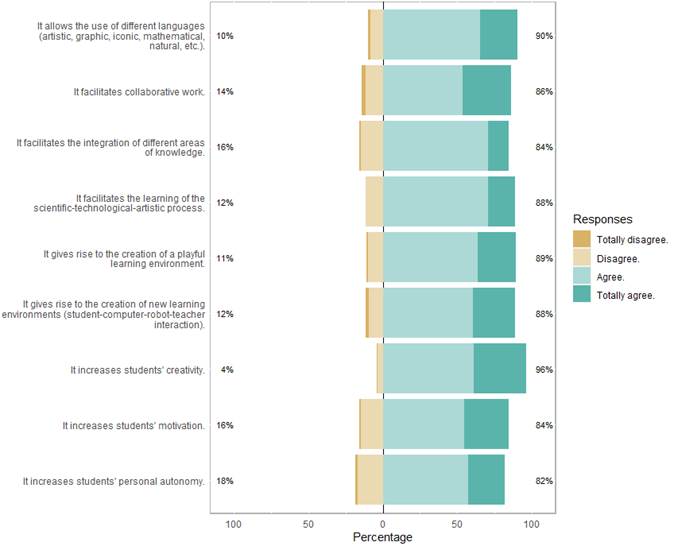

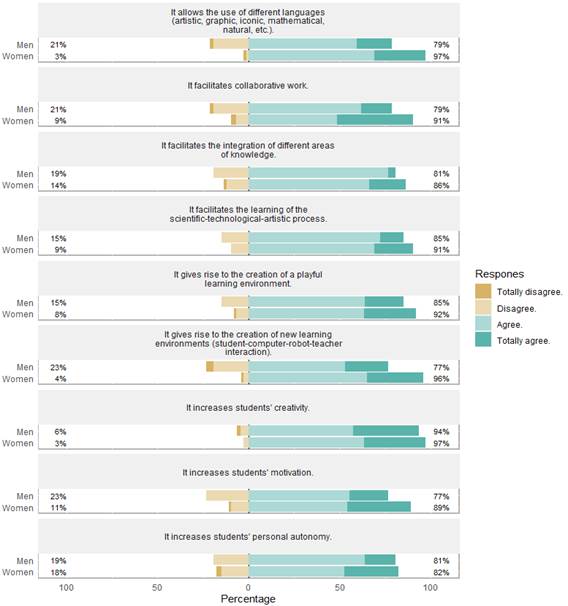

De

acuerdo a los

resultados que se muestran en la Figura 3, el grueso de los estudiantes encuestados

considera que la introducción de la robótica creativa en las aulas de Educación

Primaria se traduciría en importantes beneficios para los escolares, tales como

el incremento de su motivación, de su autonomía personal y, sobre todo, de su

creatividad.

Los participantes también

manifestaron opiniones positivas al ser preguntados por ciertos aspectos

metodológicos que se podrían derivar de la implantación de la robótica. En

concreto, casi un 90% de los estudiantes considera que la robótica facilita una

aproximación lúdica a su enseñanza-aprendizaje y un 86% de ellos opina que

propicia un entorno adecuado para el trabajo colaborativo.

También es reseñable la

percepción que tiene la mayoría de los estudiantes encuestados de la robótica

como una materia en la que confluyen diferentes áreas de conocimiento. Esta

imagen integradora de la robótica como punto de encuentro de varias disciplinas

también queda patente en las opiniones de los futuros maestros ante la

afirmación “La robótica permite el uso de diferentes lenguajes”, que son

positivas en el 90% de los casos. En la misma línea, el 88% de los alumnos ve

la robótica como un medio para el aprendizaje del proceso científico,

tecnológico y artístico.

Figura

3

Opiniones de los alumnos encuestados con respecto

a las potencialidades de la robótica creativa

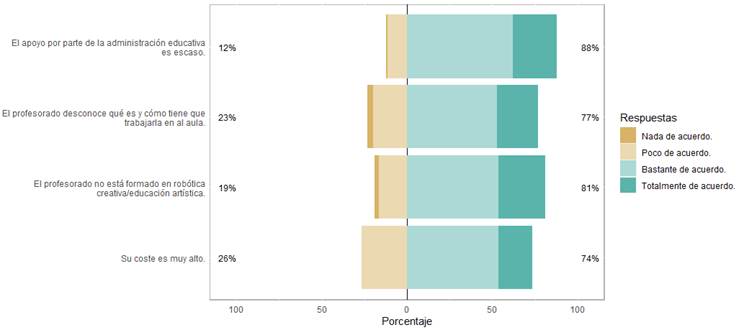

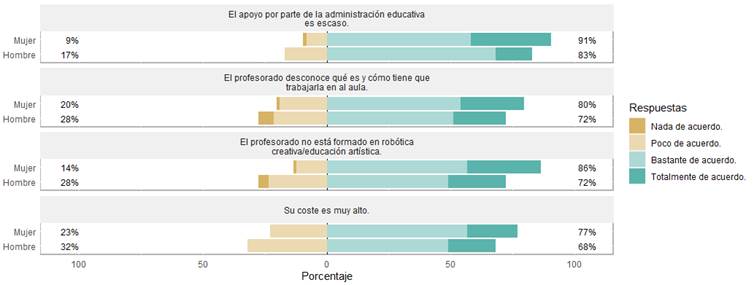

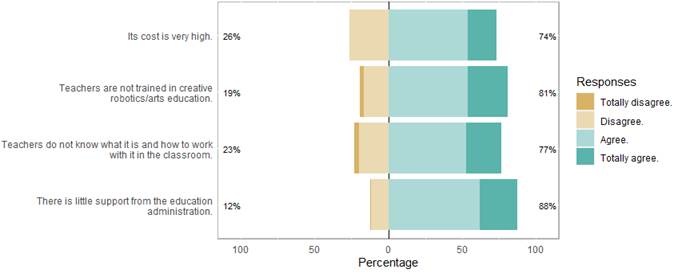

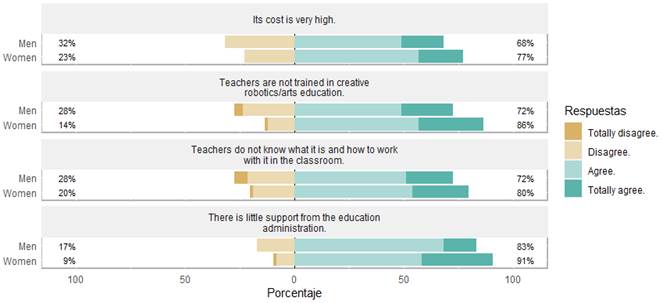

Pero, por otro lado, los

participantes en el estudio también son conscientes de la existencia de una

serie de inconvenientes que podrían obstaculizar la incorporación de la

robótica a los contenidos de la educación artística. Entre ellos destaca el

respaldo que las instituciones educativas proporcionan para la implantación de

la robótica creativa en el aula, que es percibido como insuficiente por un 88%

de los futuros maestros encuestados. Además, en torno al 75% de los

participantes indican que sería un proceso que supondría un coste muy elevado.

Por último, aspectos relacionados con el profesorado tales como la falta de

formación en robótica creativa y la insuficiente preparación didáctica para

impartirla son señalados como problemáticos para la integración de la materia

en las aulas por el 81% y el 77%, respectivamente, de los alumnos.

Figura 4

Opiniones de los alumnos encuestados con respecto a los obstáculos que

dificultarían la implantación de la robótica creativa en la educación

obligatoria

Al margen de las estas

limitaciones, los estudiantes señalaron otras entre las que destaca la carencia

de recursos, tanto humanos como materiales, para la implantación de la robótica

creativa en las aulas de Primaria.

El análisis por género de

los datos revela que hay más chicos que chicas con opiniones positivas acerca

de la conveniencia de la introducción de la robótica creativa en la educación

obligatoria, aunque esta diferencia no resulta significativa (p = 0,2746). Los

porcentajes de chicas y chicos que apoyan un enfoque

interdisciplinar para impartir la robótica en el aula (80% y 72%,

respectivamente) tampoco resultan significativamente diferentes (p = 0,4664).

Por el contrario, sí difieren de forma relevante en función del género las

opiniones sobre el carácter que tendrían que tener las

actividades de robótica en la escuela (p = 0,0003), que deberían ser

extraescolares para un mayor porcentaje de chicos que de chicas.

Figura 5

Opiniones

de los alumnos encuestados, por género, con respecto a la introducción de la

robótica creativa en la educación obligatoria

De

acuerdo a los resultados

que se muestran en la Figura 6, tanto la mayoría de los chicos (76,59%) como la

de las chicas (58,10%) opina que la robótica podría despertar vocaciones

científico-tecnológicas en el alumnado de Educación Primaria, siendo la

diferencia entre ambos porcentajes significativamente distinta de 0 (p =

0,0083). También resulta significativa la diferencia entre el porcentaje de

chicos y chicas (19,14% y 35,13%, respectivamente) que considera que, por el

contrario, la robótica suscitaría el interés de los escolares hacia áreas

humanísticas-artísticas-sociales (p = 0,0171).

Figura 6

Opiniones

de los alumnos encuestados, por género, con respecto al tipo de vocaciones que

la robótica podría despertar en el alumnado

Los resultados de la Figura

7 revelan que, en términos generales, el número de chicas que valoran

positivamente las potencialidades de la introducción de la robótica creativa en

el aula es mayor que el de los chicos. Los aspectos de la robótica que son

señalados por un mayor porcentaje de chicas son: el hecho de que fomenta de la

creatividad (97%), que permite el empleo de diversos lenguajes (97%) y que

propicia la creación de nuevos tipos de interacción (96%). Por su parte, los

chicos coinciden en indicar que la robótica puede servir para estimular la

creatividad de los alumnos (94%), aunque, a continuación, muestran los niveles

más altos de acuerdo con que favorece la creación de un ambiente lúdico (85%) y

que facilita el aprendizaje del proceso científico-tecnológico-artístico (85%)

por delante de otras ventajas.

Las diferencias en las

opiniones entre chicos y chicas que se aprecian en la muestra son

significativas a nivel poblacional únicamente en los ítems “Da pie a la creación

de nuevos entornos de aprendizaje” (p = 0,0001), “Facilita el trabajo

colaborativo” (p = 0,0293), “Incrementa la motivación del alumnado” (p =

0,0383) y “Permite el uso de diferentes lenguajes” (p = 0,0002).

Figura 7

Opiniones

de los alumnos encuestados, por género, con respecto a las potencialidades de

la robótica creativa

Por último, en la Figura 8

se puede observar que también existe una pequeña diferencia de género en cuanto

a las opiniones de los estudiantes sobre las limitaciones que podrían dificultar

la introducción de la robótica en la escuela, según la cual el porcentaje de

chicas que las perciben es ligeramente superior al de chicos. Pese a estas

diferencias, tanto chicos como chicas coinciden en señalar el insuficiente

apoyo que recibe la robótica por parte de las administraciones educativas como

el principal problema para la implantación de la robótica en las aulas.

Figura 8

Opiniones

de los alumnos encuestados, por género, con respecto a los obstáculos que

dificultarían la implantación de la robótica creativa en la educación

obligatoria

4. Discusión y conclusiones

El objetivo principal del presente

trabajo consistía en conocer la opinión de futuros maestros de Educación

Primaria acerca de la inclusión de contenidos de robótica creativa en las aulas

de Primaria.

De

acuerdo a los

resultados obtenidos, se puede concluir que, de forma global, los participantes

en el estudio consideran conveniente que los alumnos de Educación Primaria

reciban formación relacionada con la robótica creativa. Esta formación debería

formar parte de los contenidos obligatorios que los alumnos cursasen, según la

mayoría de los encuestados y que debería tener un carácter interdisciplinar.

Estos resultados coinciden con los de Clapp y Jiménez

(2016), Conradty y Bogner

(2020) y Guyotte et al. (2015) quienes señalaron que

las metodologías STEAM y la robótica creativa constituyen un enfoque de

enseñanza-aprendizaje que mantiene un carácter interdisciplinar artístico,

tecnológico y creativo. Las opiniones de los participantes sugieren que sus

percepciones van más allá de la intención pedagógica, dejando entrever la

necesidad de una formación que les permita dar respuesta a los problemas

profesionales (Domènech-Casal, 2018; Martín Páez et al., 2019). Los resultados

obtenidos coinciden con la línea de cambio en el planteamiento curricular

propuesta por Rodríguez-Sánchez y Revilla-Rodríguez (2016), según la cual se

permite a los alumnos adquirir competencias y habilidades que les permitan

desenvolverse en el mundo laboral y tecnológico, pero también a nivel

socioemocional.

Pese al estrecho vínculo que

existe entre la robótica creativa y aspectos relativos a las artes, la mayoría

de los participantes asocia la formación en robótica creativa con la

suscitación en los estudiantes de gustos o tendencias relacionadas con

disciplinas científicas o tecnológicas. Estas percepciones pueden deberse, no

solo a la naturaleza interdisciplinar de la robótica, sino también a la falta

de información, experiencia o formación en metodologías educativas que

relacionan las humanidades, el arte o las ciencias sociales con la tecnología.

Las opiniones de los estudiantes revelan la necesidad de un cambio de enfoque

en el currículo basado en una alfabetización tecnológica que se relacione no

solo con áreas científicas sino también con áreas humanísticas. Este es el

único modo de asegurar que los estudiantes pueden desarrollar investigaciones

interdisciplinares y transdisciplinares basadas en la robótica creativa que les

proporcionen la formación y las herramientas necesarias para generar

conocimiento, recursos y estrategias educativas híbridas para así generar redes

de conocimiento entre áreas científicas, humanísticas, artísticas y sociales

vinculadas a las tecnologías (Casado Fernández et al., 2020; Leoste et al., 2021).

Por otro lado, una

importante mayoría de los estudiantes es consciente de los beneficios, tanto

para el alumno como para la práctica docente, que podrían derivarse de la

inclusión de contenidos de robótica educativa en las aulas de Primaria. Estos

resultados están en concordancia con los proporcionados por estudios previos (Badeleh, 2019; Baek, 2016; Burhans y Dantu, 2017; Thuneberg et al., 2018; Wannapiroon

y Petsangsri, 2020) en los que se apunta el notable

impacto de la robótica creativa en el desarrollo personal de los estudiantes,

así como en el fomento de sus habilidades de investigación y su pensamiento

creativo. Por género, las mujeres reportaron percepciones más positivas que los

hombres respecto a las ventajas analizadas, siendo significativas las

diferencias entre géneros en algunos casos. De igual manera, los participantes

advierten las limitaciones, entendidas como obstáculos, que podrían surgir a la

hora introducir la robótica creativa en la Educación Primaria. Entre ellas,

destacan la falta de apoyo por parte de las instituciones educativas, así como

la escasa formación sobre la materia que presuponen a los docentes que se

encargarían de impartirla, coincidiendo con los resultados de investigaciones

previas (Koehler et al., 2007; Papert, 1980; Zamorano-Escalona et al., 2018).

A partir de los resultados

por género, se puede concluir que, aunque tanto la mayoría de chicos y de chicas asocian la robótica creativa con el

despertar de vocaciones científicas y tecnológicas, esta asociación cala con

más fuerza en los individuos de género masculino. Esta diferencia puede deberse a la subrepresentación

de las mujeres en las áreas STEM y en los estereotipos de géneros que

tradicionalmente han asociado las áreas relacionadas con la

ciencias y la tecnología con el género masculino, tal y como se indica

en estudios previos (Astegiano et al., 2019; Chiu, et al., 2018; García-Holgado et al., 2020). Para

equilibrar estas percepciones, los docentes encargados de impartir la robótica

creativa deberían conocer no solo sus detalles técnicos y digitales, sino

también aquellos otros aspectos relacionados con el proceso creativo-artístico

(a nivel conceptual como, por ejemplo, la estética, la alfabetización visual y

audiovisual, el componente social, el arte-diseño y la co-creación…)

que también son inherentes a la disciplina. De esta manera, se podría contribuir

a diluir esta asociación exclusiva que establecen muchos futuros maestros entre

la robótica creativa y la tecnología evitando, a su vez, su transmisión a los

que serán sus alumnos. Formar a los docentes de este modo también contribuiría

a favorecer las relaciones entre pedagogía y humanidades digitales y

posibilitar la comprensión de las nuevas relaciones y procesos educativos

híbridos que están surgiendo. Así, se permitiría poder optar por un enfoque del

proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje que incluya las artes, la innovación y la

creatividad, dándole una visión interdisciplinar más integral en la que la

creatividad se convierta en el factor clave de búsqueda de soluciones,

sensibilización y transformación. En definitiva, se conseguiría así un acercamiento

a las propuestas de la Nueva Bauhaus Europea y la Economía Creativa (industria

creativa) que introducen una dimensión cultural y creativa en el Pacto Verde

Europeo dirigida a la innovación/investigación sostenible e inclusiva para dar

respuestas positivas a problemas de nuestras vidas cotidianas.

Estas conclusiones deben

interpretarse con cautela, puesto que parten del análisis de los resultados de

una muestra de tamaño limitado y de carácter no probabilístico. En este

sentido, como ampliación de este trabajo, se pretende recoger la opinión de

estudiantes de otras universidades y compararlas con las que se han presentado.

También pretendemos comparar las opiniones de maestros en formación con la de

maestros en ejercicio, para detectar posibles diferencias.

5. Financiación

Esta investigación se enmarca dentro del Proyecto Avanzado de Innovación

Docente titulado Proyectos artísticos para la transformación social en

contextos educativos formales y no formales: arte-educación-tecnología (código

458). El Proyecto está financiado por la convocatoria de Proyectos de

Innovación y Buenas Prácticas Docentes del plan FIDO de la Universidad de

Granada para el periodo 2018-2020.

Perceptions of

future teachers on the inclusion of creative robotics in Primary Education

1. Introduction

Guidance provided by European

Parliament and Council, laid out in the Strategic Innovation Agenda of the European

Institute of Innovation and Technology for 2021/2027, suggests that key skills

training is key for the public to be able to achieve the type of personal,

professional and social development demanded by a globalised world. This type

of holistic development is stringently linked to knowledge. The complex nature

of the issues emerging in current society requires such training to include,

not only, conceptual or procedural training but, also, other abilities such as

creativity (Beghetto & Kaufman, 2013). In the present day, creativity plays

a fundamental role and assumes a split perspective. On the one hand, at an

individual level, it acts to back up the abilities of individuals so that they

can adapt to new situations and, on the other hand, at a group level, it serves

as a basic mechanism for social, scientific and technological development

(Elgrably & Leikin, 2021).

The irruption of creativity

within training needs has led to some important changes in the educational

sphere. One such change refers to the inclusion within STEM methodologies

(science, technology, engineering and mathematics), initially based on the

interdisciplinary teaching of scientific and technological content, of aspects

related with the artistic and humanistic fields. Indeed, in contemporary

society, the practice of teaching the scientific and technological disciplines

cannot be separated from critical thinking, design, communication and artistic

abilities. This has brought about incorporation of “A” for art into STEM

methodologies, giving rise to STEAM methodologies (Yakman & Lee, 2012).

STEAM methodologies constitute a teaching-learning approach that retains the

interdisciplinary nature of STEM, whilst including the artistic discipline and

creativity (Clapp & Jiménez, 2016; Conradty & Bogner, 2020; Guyotte et

al., 2015; Runco & Acar, 2012; Zawieska & Duffy, 2015). The aim of this

is to provide a response to real issues through employment of a constructionist

method that involves “learning whilst doing” (Papert, 1980; Zamorano-Escalona

et al, 2018).

Given that creativity (Runco

& Acar, 2012) is implicit in the arts and technology (Kaufman et al. 2009),

STEAM learning is crucial for promoting innovation and adaptive change. It is

critical for, not only, educational development but, also, the economic and

sustainable development of society. Taylor et al. (2017) highlights the

importance of implementing STEAM methodologies in the classroom from young ages

given that they provide students with conceptual, procedural and attitudinal

tools which enable them to provide appropriate interdisciplinary responses to

real-life issues (Domènech-Casal, 2018; Martín Páez et al., 2019).

Of all the strategies

available for the implementation of STEAM methodologies, those incorporating

educational robotics have demonstrated important benefits for different aspects

related with student learning in areas such as mathematics, physics and

engineering (Benitti, 2012), but also in the humanistic, artistic and social

fields (Casado Fernández, et al., 2020; Leoste et al., 2021).

Indeed, application of

robotics in the classroom translates to meaningful improvements in abilities

such as problem solving, social skills, reasoning and critical thinking

(Benitti, 2012; Ganesh et al., 2010; Menekse et al., 2017), graphic skills

(Mitnik et al., 2009) and the understanding of abstract concepts (Williams et

al., 2011). In the same sense, educational robotics have been shown to have a

notable impact on the personal development of students, whilst also promoting

their research abilities and critical thinking (Badeleh, 2019; Baek, 2016;

Burhans & Dantu, 2017; Thuneberg et al., 2018; Wannapiroon &

Petsangsri, 2020). Creativity can be promoted, for example, through programming

and the construction and handling of both software and hardware (Badeleh, 2019;

Baek, 2016; Caballero-González & García-Valcárcel, 2020; Cabello-Ochoa

& Carrera-Farrán, 2017; Kahn et al.,

2016; Zawieska & Duffy, 2015), stimulating the ability of students to learn

through experience with their environment and to transfer this knowledge in

order to respond to issues in a novel way. Existing research demonstrates the

utility of daily experiences for promoting the development of creativity and

innovation (Nemiro et al., 2017). For example, it is well demonstrated that

teaching-learning processes based on robotics improve creativity in an

effective way, whilst also favouring all of the components that make it up,

namely, originality, elaboration, flexibility and fluidity.

Reviewed literature pertains

to, mainly, examinations of the effects of educational robotics performed in

primary and secondary school settings (up until K12) (Bers & Urrea, 2000;

Dias et al., 2005; Resnick, 1993), in technical and vocational schools

(colleges) (Alimisis et al, 2005), and in extra-curricular programs (Barker

& Ansorge, 2007; Rusk et al., 2008). When considering educational level,

research emerges that explores the impact of using robotics kits when

developing the skills and abilities of students in early and primary education.

Such research proposes the use of a social and cultural technological framework

(Jung & Won, 2018). Other research studies focus on specific aspects of

robotics, such as creative programming and computational thinking in primary

education (Bers et al., 2019; González-González, 2019; Maya et al., 2015;

Moreno et al., 2019; Sáez-López et al., 2021; Vivas-Fernández & Sáez-López,

2019), highlighting positive outcomes and improvements in the digital and

technological abilities of students using educational robotics during the

primary and secondary stages of education (Lin et al., 2005; Relkin et al.,

2020; Xia & Zhong, 2018).

Despite its benefits, the

implementation of creative robotics, in particular, and STEAM methodologies, in

general, in the classroom presents a number of challenges that make some

teachers question their use. This is due to a lack of understanding about the

meaning of the STEAM methodologies and their pedagogical potential for

addressing different languages, concepts or personal expressions and meaning

(Chen & Huang, 2020; Herro & Quigley, 2017; Yakman, 2008). Indeed,

implementation of these methodologies implies a number of changes, with regards

to traditional methodologies, which have a direct influence on the day-to-day

delivery of teaching in classrooms. As the main implementers of these changes,

teachers play a fundamental role in this new educational reality, highlighting

the need for up-to-date teacher training. Such training is currently being

specified in terms of both content and the strategies and resources to be

implemented in the classroom (Grover & Pea, 2013).

Within this new educational

landscape, within the skills that must be acquired by students, the development

of attitudes promoting gender equality and non-sexist behaviours is also

included, with a concomitant impact on professions related with science and

technology from a gender perspective. This aspect is especially relevant in the

fields covered by STEAM methodologies, in which the presence and participation

of women is scarce when compared with that of men (Astegiano et al., 2019;

Chiu, et al., 2018; García-Holgado et al., 2019; García-Holgado et al., 2020).

Significant data has also been presented in research conducted by Cimpian et

al. (2020), which indicate that, from seven-years onwards, girls already feel

inferior than boys when it comes to their ability to solve problems based on

STEAM methodologies. Other findings lead us to reflect on the gender gap found

in scientific and technological vocations, as laid out in reports such as

Cracking the Code (UNESCO, 2019), The ABC of Gender Equality in Education

(OECD, 2015) and Equality in Numbers 2020 by the Ministry of Education and

Professional Training. Given this, the European Commission considers inclusion,

equity and vocational development to be a priority in STEAM fields. This

challenge is laid out in the strategic framework for European cooperation, in

the ambit of education and training in the European Education Area 2021-2030,

and in the Sustainability Goals (ODS) described in the 2030 Agenda. This shows

that inclusive education and training also implies developing greater gender

sensitivity in the learning processes and educational institutions. At the same

time, it leads to the questioning and dissolution of gender stereotypes, above

all, those that limit the choices available to children in relation to their

field of study. Amongst the projects developed to tackle this challenge, the

Digital Education Action Plan 2021-2027 and Digital Plan for Spain 2025 are

found. The main aims of these are to move education into the digital era and

promote female participation in STEAM studies, whilst also engaging the

educational system to promote the development of scientific and technological

vocations without abandoning the arts. At a state level, the Ministry of

Education, Training and Employment created the STEAM Alliance for Female Talent

as a strategy to reduce the gap between male and female students. Similarly,

Girls Standing Up in Science reports the most up-to-date data on this issue,

which was gathered by the study X-raying the Gender Gap in STEAM Training

(2022) performed by the Ministry of Education on the educational trajectory of

girls and women in Spain.

The present study aims to

identify the opinions of prospective primary school teachers about the

inclusion of educational robotics in primary school classrooms. It examines

perceptions about the pedagogical strengths and limitations brought about by

the incorporation of this discipline at the aforementioned educational stage.

Specifically, we posed the following research questions:

1. What is the opinion of future teachers regarding the inclusion of

creative robotics in the primary school curriculum?

2. What kind of future vocations might creative robotics inspire in

students?

3. What strengths and limitations regarding the inclusion of creative

robotics in the classroom do future teachers perceive?

4. Are there any gender differences among prospective teachers in their

opinions about the inclusion of educational robotics in the classroom?

2. Methods

Participants in the present

study were 121 students, comprising 74 women (61.16%) and 47 men (38.84%),

undertaking the first year of a Primary Education degree at the University of

Granada. Participants were selected by convenience. The majority (80.43%) were

had gained entry to the course following achievement of baccalaureate studies.

The academic settings in which students considered themselves to have stood out

throughout their academic career were physical education (28.92%), citizenship

(21.48%), linguistics (17.35%), artistic (14.87%), mathematics (14.04%) and, to

a lesser extent, knowledge of social media, knowledge of natural media and

technology.

An adapted version of a

questionnaire developed by Cabello-Ochoa and Carrera-Farrán (2017) provided the

data collection tool. This questionnaire was created for the purpose of

gathering information on the attitudes and beliefs of students practicing in

primary education and early education regarding the implementation of creative

robotics in classrooms. Given that the present study was directed towards

teachers still at the university training stage, it was necessary to modify

some of the original questionnaire items. The biggest changes were made to

questions that were sociodemographic in nature. In this sense, items previously

examining the professional baggage of practicing teachers, were modified in the

adapted version in order to gather information on the academic and training

trajectory of students. In the same way, items collecting data on the length of

experience in teaching and the educational level at which practicing teachers

conducted the majority of their professional activity were removed given that

they would not be relevant for trainee teachers.

The final adapted version of

the questionnaire started with 5 questions that were sociodemographic in

nature. These were followed by 20 questions which gather information on

perceptions about the incorporation of this content within mandatory teaching.

With regards to design of the original questionnaire proposed by the authors, a

4-point Likert scale was used (totally disagree, slightly agree, largely agree,

totally agree) to gather information on the opinions of surveyed participants.

The questionnaire also included multiple-choice and single-option questions,

with one question affording open responses.

The calculation of the

reliability and internal consistency of the questionnaire for the measurement

of the single underlying construct, "Students' perceptions of the inclusion

of educational creative robotics in Primary Education", was carried out

using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Then, gathered data were analysed, mainly,

using descriptive techniques. Following analysis of the overall dataset in

relation to the whole sample, responses were examined separately according to

gender. In order to check whether responses given by males and females differed

in a meaningful way, contrasts of proportions were carried out. These

constrasts were found to reveal significant differences when associated with a

p-value lower than .05.

3. Analysis and results

Cronbach's alpha coefficient

yielded a value of 0.79, which, according to George and Mallery (2003), indicates

an acceptable level of reliability of the questionnaire, very close to a good

level.

Overall, as reflected in

Figure 1, the majority of surveyed students reported favourable opinions with

regards to the introduction of creative robotics as a part of the mandatory

teaching of artistic education. Further, almost 70% of participants considered

that content pertaining to robotics should not be delivered outside of the

curriculum but, instead, should be delivered in the classroom as part of the

official curriculum. In addition, more than three quarters of students

considered it important to take an interdisciplinary perspective when

approaching the teaching of this content.

Figure 1

Surveyed students’ opinions regarding

the introduction of creative robotics into mandatory education

Due, perhaps, to this

multidisciplinary nature, surveyed participants provided diverse opinions about

the type of vocations that could be supported by robotics training in primary

school students. These outcomes are presented in Figure 2. According to more

than 65% of participants, vocations were likely to be related with the

scientific-technological field, whilst just under 30% of participants believed

that they would be humanistic-artistic-social in nature. Just 3.3% of students

considered that paths could be opened up equally in both fields.

Figure 2

Surveyed students’ opinions

regarding the types of career paths likely to be opened up by robotics training

in students

As shown by the outcomes presented

in Figure 3, the large bulk of surveyed students considered that the

introduction of creative robotics into primary school classrooms would

translate into important benefits for students, such as greater motivation,

personal autonomy and, above all, creativity.

Participants also reported

positive opinions when they were asked about certain methodological aspects

deriving from the introduction of robotics. Specifically, almost 90% of

students considered robotics to facilitate a fun approach to learning, whilst

86% believed that robotics provided an appropriate setting for collaborative

working.

It is also notable that the

majority of surveyed students perceived robotics to be a subject that dipped in

to different knowledge fields. This image of robotics as the meeting point for

a number of disciplines clearly emerged in the opinions reported by future

teachers and can be seen through the fact that 90% of individuals positive

rated the statement “robotics enables the use of different languages”. Along

the same lines, 88% of students viewed robotics as a means towards learning

scientific, technological and artistic processes.

Figure 3

Surveyed students’ opinions

regarding the advantages of creative robotics

On the other hand, study

participants were also aware of the existence of a number of disadvantages

which could impede the incorporation of robotics within the teaching of

artistic education. One such disadvantage lies in the need for educational

institutions to provide full support for the introduction of creative robotics

in the classroom, with this support being perceived as insufficient by 88% of

the future teachers surveyed. Further, around 75% of participants indicated that

the process of implantation would be hugely costly. Finally, aspects related

with teaching staff, such as a lack of training in creative robotics and

insufficient didactic preparation for delivering classes on the topic, were

indicated by 81% and 77% of students, respectively, as constituting a challenge

to the integration of content in classrooms.

Figure 4

Surveyed students’ opinions regarding

the barriers impeding the introduction of creative robotics into compulsory education

Outside of these limitations,

participating students outlined other limitations, with the lack of both human

and material resources for the integration of creative robotics into primary

school classrooms standing out.

Gender-based analysis of the

gathered data revealed that more males than females reported positive opinions

about the usefulness of the introduction of creative robotics into compulsory

education, although differences were not statistically significant (p = .2746).

The proportion of students that supported taking an inter-disciplinary approach

to delivering robotics content in classrooms was also found not to differ

according to gender (80% and 72% in males and females, respectively) (p =

.4664). In contrast, differences were found as a function of gender in opinions

about the required nature of robotics classroom activities (p = .0003).

Specifically, more males than females reported that activities should be

extra-curricular in nature.

Figure 5

Surveyed students’ opinions

regarding the inclusión of creative robotics within compulsory

education, as a function of gender

In accordance with the

findings presented in Figure 6, the majority of both males (76.59%) and females

(58.10%) believed that robotics could open career paths in

scientific-technological fields for students studying primary education, with

gender-based differences also being statistically significant (p = .0083). The

percentage of males and females that considered robotics to, in contrast to the

outcomes reported above, lead to a greater interest of students in

humanistic-artistic-social fields (19.14% and 35.13%, respectively) was also

statistically significant (p = .0171).

Figure 6

Surveyed students’ opinions

regarding the types of career path interests that robotics could encourage, as

a function of gender

Findings presented in Figure 7

revealed that, in general terms, a higher number of females than males

positively rated the potential benefits of including creative robotics teaching

in classrooms. The positive aspects of robotics most commonly indicated by

females were the following: It promotes creativity (97%), it encourages the use

of different languages (97%) and it leads to the creation of new types of

interaction (96%). In the case of males, they agreed that robotics could serve

to stimulate creativity in students (94%), however, in contrast, they reported

greater agreement with the argument that robotics favours the creation of a fun

environment (85%) and facilitates the learning of

scientific-technological-artistic processes (85%), finding these advantages to

be more pertinent than others.

Opinions reported by males and

females were only found to be significantly different in the case of the items

“[robotics] gives rise to the creation of new learning environments” (p =

.0001), “Robotics facilitates collaborative working” (p = .0293), “Robotics

increases student motivation” (p = .0383) and “Robotics encourages the use of

different languages” (p = .0002).

Figure 7

Surveyed students’ opinions

regarding the advantages of creative robotics, as a function of gender

Finally, in Figure 8, it can

be observed that a slight gender effect exists with regards to student opinions

regarding the limitations that could impede the introduction of robotics at

school. Specifically, slightly more females than males perceived limitations to

exist. Despite these differences, both males and females agreed that the main

barrier to implementing robotics in the classroom was the inadequate support

received by educational institutions to this end.

Figure 8

Surveyed students’ opinions

regarding the barriers impeding the implementaion of

creative robotics in compulsory education, as a function of gender

4. Discussion and conclusions

The main aim of the present work

was to uncover the perceptions of future primary school teachers regarding the

inclusion of creative robotic content in primary education classrooms.

In accordance with obtained

outcomes, it can be concluded that, generally speaking, study participants

believed it would be useful for primary school students to receive training

related with creative robotics. The majority of those surveyed reported that

such training should form part of the compulsory content imparted to students

and that it should be interdisciplinary in nature. These results are in line

with those of Clapp and Jiménez (2016), Conradty and Bogner (2020) and Guyotte

et al. (2015) who indicate that STEAM methodologies and creative robotics

constitute a teaching-learning approach that maintains an interdisciplinary

artistic, technological and creative character. The views of the participants

suggest that their perceptions go beyond the pedagogical intention, with the

need for training that allows them to respond to professional problems (Domènech-Casal,

2018; Martín Páez et al., 2019). The results obtained coincide with the line of

change in the curricular approach proposed by Rodríguez-Sánchez and

Revilla-Rodríguez (2016), which enables students to acquire the skills and

abilities that allow them to develop in the world of work and technology, but

also on a socioemotional level.

Despite the tight link found

to exist between creative robotics and aspects relative to the arts, most

participants associated the training of students in creative robotics with

bringing out desires and tendencies related with scientific and technological

disciplines. These perceptions may be due not only to the interdisciplinary

nature of the methodology, but also to the lack of information, experience or

training in educational processes linking humanities, arts or social areas with

technologies. The students' opinions highlight the need for a change of

curricular approach based on technological literacy linked not only to

scientific areas but also to humanities. This is the only way to ensure that

students can develop interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research based on

creative robotics that will provide them with the training and tools necessary

to generate knowledge, resources and hybrid educational strategies that will

enable them to generate knowledge networks between scientific and humanistic,

artistic and social areas linked to technologies (Casado Fernández et al.,

2020; Leoste et al., 2021).

In another sense, a large majority

of students was aware of the benefits for both students and exercising teachers

that could be brought about by the inclusion of educational robotics teaching

in primary school classrooms. These data are in line with those provided by

previous studies (Badeleh, 2019; Baek, 2016; Burhans and Dantu, 2017; Thuneberg

et al., 2018; Wannapiroon and Petsangsri, 2020) which point to the remarkable

impact of creative robotics on students' personal development, as well as on

fostering their research skills and creative thinking. By gender, females

reported more positive perceptions of examined advantaged than males, with

gender differences being significant in some cases. In the same way,

participants also mentioned certain limitations, understood as barriers, that

could arise at the time of introducing creative robotics into primary

education. Of these limitations, a lack of support from educational

institutions most stood out, alongside shortcomings in the training on offer

for teachers to deliver such material, in line with the findings of previous

studies (Koehler et al., 2007; Papert, 1980; Zamorano-Escalona et al., 2018).

In consideration of

gender-based outcomes, it can be concluded that, although the majority of both

males and females associated creative robotics with the awakening of scientific

and technological vocations, this association emerged more strongly within

males. These differences may be due to the under-representation of women in

STEM fields and gender stereotypes that have traditionally associated science

and technology fields with the male gender, as reflected in previous studies

(Astegiano et al., 2019; Chiu, et al., 2018; García-Holgado et al., 2020). In

order to balance out these perspectives, teachers charged with delivering

content on creative robotics should, not only understand its technical and

digital features but, also, be familiar with other aspects related with

creative-artistic processes (at a conceptual level such as, for example,

aesthetics, visual and audio-visual literacy, social components, art and

design, and co-creation…) which are also inherent to the discipline. In this

way, the tendency of many future teachers to perceive creative robotics to be

exclusively linked with technology and, therefore, transmit this to their students,

may be wavered. Equipping teachers in this way would also contribute towards

favouring the relationship between pedagogy and digital humanities, making

understanding of new relationships and emerging hybrid educational processes

more likely. This would enable an approach to be taken that includes the arts,

innovation and creativity, providing a more comprehensive inter-disciplinary

perspective, in which creativity becomes the key factor to problem solving,

awareness raising and transformation. In conclusion, consideration of these

aspects would move us closer towards achieving proposals laid out by the New

European Bauhaus and the Creative Economy (creative industry). Specifically,

the introduction of cultural and creative dimensions in the European Green

Deal, directed towards sustainable and inclusive innovation/research as a means

to providing positive responses to daily issues.

Present findings should be interpreted with caution given that they are

based on data produced using a relatively small convenience sample. In this

sense, as an extension of the present work, it would be useful to gather

information on the opinions of students attending other universities and

compare findings with those presented in the present study. Another useful future

direction would be to compare the perspectives of trainee teachers with those

working professionally with a view to detecting potential differences.

5. Funding

This research is part of the

Advanced Teaching Innovation Project entitled: Artistic projects for social

transformation in formal and non-formal educational contexts:

art-education-technology (Code 458). Under the Call for Teaching Innovation

Projects and Best Practices of the FIDO Plan, University of Granada, carried

out in the period from 2018 to 2020.

References

Alimisis, D., Karatrantou, A., &

Tachos, N. (2005). Technical school students

design and develop robotic gear-based constructions for the transmission of

motion. In G. Gregorezyk, A. Walat, W. Kranas, & M. Borowiecki (Eds.), Digital tools for

lifelong learning (pp. 76-86). DrukSfera.

Astegiano, J., Sebastián-González, E., & Castanho, C. T.

(2019). Unravelling the gender productivity gap in science: a meta-analytical

review. Royal Society open science, 6(6),

181566. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181566

Badeleh, A. (2019). The effects of robotics training on

students’ creativity and learning in physics, Education and Information Technologies, 26,

1353-1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09972-6

Baek, J. E. (2016). Effects of

Robot-Based Learning on Learners Creativity. Proceedings of the 9th International Interdisciplinary Workshop Series,

Advanced Science and Technology Letters, 127, 130-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/astl.2016.127.26

Barker, B. S., & Ansorge,

J. (2007). Robotics as means to increase achievement scores in an informal

learning environment. Journal of Research

on Technology in Education, 39(3), 229–243. https://doi.org/

10.1080/15391523.2007.10782481

Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2013). Fundamentals of

creativity. Educational Leadership, 70(5),

10–15.

Benitti, F. B. V. (2012). Exploring the educational potential

of robotics in schools: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 58(3), 978–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.006

Bers, M. U., & Urrea. C.

(2000). Technological prayers: Parents and children working with robotics and

values. En A. Druin y J. Hendler (Eds.), Robots for kids: Exploring new technologies for learning experiences (pp.

194-217). Morgan Kaufmann.

Bers, M. U., González-González, C., & Armas–Torres, M.

B. (2019). Coding as a playground:

Promoting positive learning experiences in childhood classrooms. Computers

& Education, 138, 130-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.013

Burhans, D., & Dantu, K.

(2017). ARTY: Fueling Creativity through Art, Robotics and Technology for

Youth. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference

on Artificial Intelligence, 31(1).

https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v31i1.10552

Caballero-González,

Y. A., & García-Valcárcel, A. (2020). ¿Aprender con robótica en Educación

Primaria? Un medio de estimular el pensamiento computacional. Education in the Knowledge Society (EKS), 21,

15. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.22957

Cabello-Ochoa,

S., & Carrera-Farrán, X. (2017). Diseño y

validación de un cuestionario para conocer las actitudes y creencias del

profesorado de educación infantil y primaria sobre la introducción de la

robótica educativa en el aula. EDUTEC,

Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, 60. https://doi.org/10.21556/edutec.2017.60.871

Casado Fernández, R., & Checa Romero, M. (2020).

Robotics and STEAM projects: Development of creativity in a primary school

classroom. Pixel-Bit, Revista de Medios y Educación, 58, 51-69. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.73672

Chen, C. C., & Huang, P.

H. (2020). The effects of STEAM-based mobile learning on learning achievement

and cognitive load. Interactive Learning

Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1761838

Chiu, M., Roy, M., & Liaw,

H. (2018). The Gender Gap in Science. Chemistry

International, 40(3), 14-17. https://doi.org/10.1515/ci-2018-0306

Cimpian, J. R., Kim, T. H., & McDermott, Z. T. (2020).

Understanding persistent gender gaps in STEM. Science, 368(6497), 1317-1319. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba7377

Clapp, E. P., & Jiménez,

R. L. (2016). Implementing STEAM in maker-centered learning. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and

the Arts, 10(4), 481-491. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000066

Conradty, C., & Bogner, F. X. (2018). From STEM to STEAM:

How to monitor creativity. Creativity

Research Journal, 30(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2018.1488195

Decision 2021/820 of the

European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2021 on the Strategic

Innovation Agenda of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT)

2021-2027. Retrieved from http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/2021/820/oj

Dias, M. B., Mills-Tettey, G.

A., & Nanayakkara, T. (2005). Robotics, education, and sustainable

development. In Proceedings of the 2005

IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2005), (pp.

4248–4253). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBOT.2005.1570773

Domènech-Casal,

J. (2018). Aprendizaje basado en proyectos en el marco STEM. Componentes

didácticas para la competencia científica. Ápice,

2(2), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.17979/arec.2018.2.2.4524

Elgrably, H., & Leikin, R.

(2021). Creativity as a function of problema-solving

expertise: Posing new problems through investigations. ZDM—Mathematics Education 53(4), 891–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-021-01228-3

Ganesh, T., Thieken, J.,

Baker, D., Krause, S., Roberts, C., Elser, M., Taylor, W., Golden, J.,

Middleton, J., & Kurpius, S. R. (2010). Learning

through engineering design and practice: implementation and impact of a middle

school engineering-education program. Ponencia presentada en 2010 ASEE Annual

Conference and Exposition,

Louisville.

García-Holgado,

A., Verdugo-Castro, S., González, C., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., & García

Peñalvo, F. J. (2020). European Proposal to Work in

the Gender Gap in STEM: A Systematic Analysis. IEEE Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnologías del Aprendizaje, 15(3), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1109/RITA.2020.3008138

García-

Holgado, A., Camacho Díaz, A., & García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2019). La brecha de género en el sector STEM en America Latina: una propuesta europea. In M. L. Sein-Echaluce Lacleta, Á. Fidalgo-Blanco, & F. J. GarcíaPeñalvo (Eds.). Actas del V Congreso Internacional

sobre Aprendizaje, Innovación y Competitividad. CINAIC (pp. 704-709). Universidad de Zaragoza. https://doi.org/10.26754/CINAIC.2019.0143

George, D., & Mallery, P.

(2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A

simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Grañeras Pastrana, M., Moreno Sánchez, M. E., & Isidoro

Calle, N. (2022). Radiografía de la

brecha de género en la formación STEAM. Un estudio en detalle de la trayectoria

educativa de niñas y mujeres en España. Ministerio de Educación y Formación

Profesional.

Grover,

S., & Pea, R. (2013). Computational Thinking in

K–12: A Review of the State of the Field. Educational Researcher, 42(1), 38-43. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12463051

González-González,

C. S. (2019). Estado del arte en la enseñanza del pensamiento computacional y

la programación en la etapa infantil. Educación

en la sociedad del conocimiento, 20, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks2019_20_a17

Guyotte, K. W., Sochacka, N.

W., Costantino, T. E., Kellam, N. N., & Walther, J. (2015). Collaborative

creativity in STEAM: Narratives of art education students’ experiences in

transdisciplinary spaces. International

journal of education & the arts, 16(15),

1-39.

Herro, C., & Quigley, C.

(2017) Exploring teachers’ perceptions of STEAM teaching through professional

development: Implications for teacher educators Professional Development in Education, 43(3), 416-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2016.1205507

Jung, S., & Won, E.

(2018). Systematic Review of Research Trends in Robotics Education for Young

Children. Sustainability, 10(4), 905.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040905

Kahn, P. H., Kanda, T.,

Ishiguro, H., Gill, B. T., Shen, S., Ruckert, J. H., & Gary, H. E. (2016).

Human creativity can be facilitated through interacting with a social robot. In 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International

Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) (pp. 173-180). https://doi.org/10.1109/HRI.2016.7451749

Kaufman, J. C., Cole, J. C.,

& Baer, J. (2009). The construct of creativity: Structural model for self- reported creativity ratings. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 43(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2009.tb01310.x

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P.,

& Yahya, K. (2007). Tracing the development of teacher knowledge in a

design seminar: Integrating content, pedagogy and

technology. Computers & Education, 49(3),

740-762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.11.012

Leoste, J., Jögi, L., Õun, T.,

Pastor, L., San Martín López, J., & Grauberg, I.

(2021). Perceptions about the future of integrating emerging technologies into

higher education – the case of robotics with artificial intelligence. Computers, 10(9), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers10090110

Lin, J. M. C., Yen, L. Y.,

Yang, M. C., & Chen, C. F. (2005). Teaching computer programming in

elementary schools: a pilot study. In National

educational computing conference.

Maya, I., Pearson, J. N.,

Tapia, T., Wherfel, Q. M., & Reese, G. (2015).

Supporting all learners in school-wide computational thinking: A cross-case

qualitative analysis. Computers & Education, 82, 263-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.022

Martín‐Páez, T., Aguilera, D., Perales‐Palacios, F. J., & Vílchez‐González, J. M. (2019). What are we talking about when we talk about STEM

education? A review of literature. Science

Education, 103(4), 799–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21522

Ministry of Education and

Professional Training (2020). Igualdad en cifras MEFP 2020. Aulas por la igualdad. Ministerio de Educación y Formación

Profesional.

Menekse, M., Higashi, R., Schunn, C. D., & Baehr, E.

(2017). The role of robotics teams’

collaboration quality on team performance in a robotics tournament. Journal of Engineering Education, 106(4),

564-584. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20178

Mitnik, R., Recabarren, M., Nussbaum, M., & Soto, Á. (2009).

Collaborative robotic instruction: a graph teaching experience. Computers & Education, 53, 330-342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.02.010

Moreno,

J., Robles, G., Román, M., & Rodríguez, J. D. (2019). No es lo mismo: un

análisis de red de texto sobre definiciones de pensamiento computacional para

estudiar su relación con la programación informática. RIITE Revista Interuniversitaria de Investigación en Tecnología

Educativa. 82, 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.11.022

Naciones

Unidas. (2018). La Agenda 2030 y los

Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: una oportunidad para América Latina y el

Caribe (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3).

Nemiro, J., Larriva, C., & Jawaharlal,

M. (2017). Desarrollando el comportamiento creativo en estudiantes de primaria

con robótica. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 51(1), 70-90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.87

Nussbaum, M. C. (2010). Sin fines de lucro. Por qué la democracia necesita de

las humanidades. (Rodil, M.V., trad.). Katz.

OECD. (2015). The ABC of Gender Equality in Education:

Aptitude, Behaviour, Confidence. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264229945-en

Papert,

S. (1980). Mindstorms: niños, computadoras e ideas poderosas.

Libros básicos.

Relkin, E., de Ruiter, L., & Bers, M. U. (2020). TechCheck:

Development and validation of an unplugged assessment of computational thinking

in early childhood education. Journal of

Science Education and Technology, 29(4),

482-498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-020-09831-x

Resnick,

M. (1993). Kits de construcción de comportamiento. Comunicaciones de la ACM, 36(7), 64-71. https://doi.org/10.1145/159544.159593

Rodríguez-Sánchez,

M., & Revilla-Rodríguez, P. (2016). Las competencias generales y

transversales del Grado en Logopedia desde la perspectiva del alumnado. Educatio Siglo

XXI, 34(1), 113-136.

Runco, M. A., & Acar, S.

(2012). Divergent thinking as an indicator of creative potential. Creativity research journal, 24(1), 66-75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.652929

Rusk, N., Resnick, M., Berg,

R., & Pezalla-Granlund, M. (2008). New pathways

into robotics: Strategies for broadening participation. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 17(1), 59-69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-007-9082-2

Sáez

López, J. M., Buceta Otero, R., & Lara García-Cervigón, S. D. (2021). Introducing robotics and block programming in elementary education. RIED. Revista

Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 24(1), 95-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ried.24.1.27649

Taylor, M. S., Vasquez, E.,