Videoanálisis de indagaciones científicas en la

formación inicial docente: identificación de T-patterns

Video analysis of scientific inquiry in preservice teacher

education: Identification of T-patterns

Dña. Maria Carme

Peguera-Carré. Investigadora Predoctoral. Facultad

de Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dña. Maria Carme

Peguera-Carré. Investigadora Predoctoral. Facultad

de Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dr. Andreu

Curto-Reverte. Investigador Postdoctoral (Margarita

Salas). Facultad de Educación, Psicología y

Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dr. Andreu

Curto-Reverte. Investigador Postdoctoral (Margarita

Salas). Facultad de Educación, Psicología y

Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dr. Jordi L.

Coiduras-Rodríquez. Profesor agregado. Facultad de

Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dr. Jordi L.

Coiduras-Rodríquez. Profesor agregado. Facultad de

Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dr. David

Aguilar-Camaño. Profesor agregado. Facultad de

Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Dr. David

Aguilar-Camaño. Profesor agregado. Facultad de

Educación, Psicología y Trabajo Social. Universidad de Lleida, España

Recibido:2022/10/24; Revisado:2022/11/02; Aceptado:2023/02/25; Preprint:2023/04/14; Publicado:2023/05/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Peguera-Carré,

M.C., Curto-Reverte, A., Coiduras-Rodríquez, J.,

& Aguilar-Camaño, D. (2023). Videoanálisis de

indagaciones científicas en la formación inicial docente: identificación de T-patterns [Video analysis of scientific inquiry

in preservice teacher education: T-patterns identification]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de

Medios y Educación, 67, 123-153. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.96894

RESUMEN

La observación en la

formación inicial de docentes se ha visto favorecida con la proliferación de herramientas

digitales para el análisis de la actuación en el aula, junto a las prestaciones

introducidas en el software para tratamientos más complejos de los datos. La

literatura refiere la eficacia de las prácticas de videoanálisis

en la transmisión y adquisición del conocimiento pedagógico. En este estudio pre-experimental se presentan los resultados de un proceso

formativo basado en la observación y análisis de secuencias videográficas sobre

indagación científica y su enseñanza en educación primaria. Los registros

audiovisuales de treinta estudiantes del grado de educación primaria

conduciendo sesiones de ciencias experimentales, antes y después del proceso

formativo, muestran en el análisis estadístico y en los T-patterns

una mejora en la apropiación de modelos didácticos basados en la indagación.

Los docentes en formación inicial transitan desde una primera actuación basada

en demostraciones científicas guiadas a una intervención posterior estructurada

bajo planteamientos característicos de la práctica de investigación, con una

mayor diversidad y movilización de las habilidades científicas acompañadas de

ayudas pedagógicas.

ABSTRACT

Observation practices in

initial teacher training has been favoured by the

proliferation of digital tools for the analysis of classroom performance and

the latest developments in software for new and more complex data processing.

The literature refers to the effectiveness of video analysis practices in the

transmission and acquisition of pedagogical knowledge in higher education. This

pre-experimental study presents the results of a training process based on the

observation and analysis of video sequences about scientific inquiry and its

teaching in primary education. The audiovisual recordings, before and after the

training process, of thirty preservice primary education teachers conducting

experimental science lectures show, in the statistical studies and in the

T-patterns performed, an improvement in the appropriation of didactic models

based on inquiry. The preservice teachers progress from initial performances

based on guided scientific demonstrations to later interventions that show a

more inquiry-based approach where a greater diversity and mobilisation

of scientific skills accompanied by pedagogical aids have been identified.

PALABRAS CLAVES· KEYWORDS

Formación preparatoria de

docentes, observación, grabación en vídeo, proceso de enseñanza, estrategias en

la investigación.

Preservice teacher education, observation, video

recordings, instruction, research strategies

1. Introducción

El presente estudio expone cómo

la observación de eventos docentes facilita la transferencia teoría-práctica y

la transmisión de conocimiento pedagógico en la formación inicial de maestros

(Zaragoza et al., 2021). Estas observaciones se han visto favorecidas por el

vídeo, en línea con su uso creciente en la educación formal (Alpert & Hodkinson, 2019; Pattier & Ferreira, 2022). El material audiovisual

permite el acceso a situaciones reales de aula para la selección de fragmentos

de actuaciones docentes de referencia. El análisis de los eventos relevantes

permite a los Docentes en Formación Inicial (DFI) construir conocimiento

específico de una disciplina, promover la reflexión y participar más efectiva y

creativamente en su actividad práctica (Gaudin & Chaliès, 2015; Richards et al., 2021). Sherin

et al. (2011) y Goodwin (1994) afirman que el videoanálisis

permite atender selectivamente a eventos relevantes en el aula para identificar

e interpretar los acontecimientos observados y relacionarlos con conceptos y

teorías. Colomo-Magaña et al. (2020) subrayan que combinar estas prácticas de

observación con recursos audiovisuales ayuda a dinamizar una formación dirigida

a una generación, asiduamente, prosumidora en el entorno sociopersonal.

Además, el uso del vídeo aporta flexibilidad y fomenta la autonomía y la

autorregulación de los DFI durante su proceso de aprendizaje.

Esta investigación se sitúa

en el ámbito de las ciencias experimentales y, concretamente, en el uso del videoanálisis para promover prácticas de indagación

científica en DFI de educación primaria.

1.1. Desarrollo de prácticas

indagadoras en educación primaria

Las políticas educativas

internacionales remarcan la importancia de implementar metodologías de

aprendizaje basadas en la indagación en la enseñanza de las ciencias experimentales

(National Research Council,

2012; Pedaste et al., 2015). Esta metodología se

puede entender como la transposición didáctica de la investigación y consiste

en la capacidad para planificar y realizar diseños experimentales que permitan

a los discentes responder preguntas y solucionar problemas (Harlen,

2013).

En primer lugar, la

indagación implica desarrollar un conjunto de habilidades científicas, que se entienden como las actividades que

reflejan tareas reales que realizan los científicos. Estas implican la

capacidad de aplicar reglas o principios sobre el diseño y la ejecución de una

investigación científica (Harlen & Qualter, 2009). Durmaz y Mutlu (2016), Özgelen (2012) y Rönnebeck et al. (2016), en una propuesta de síntesis,

enumeran y definen las siguientes habilidades

científicas de un proceso indagador: observar, cuestionar, hipotetizar,

diseñar una investigación bajo el control de variables, interpretar y

comunicar.

En segundo lugar, como en

todo proceso de enseñanza, la implementación de las diferentes habilidades

científicas en el aula también conlleva el acompañamiento de unas acciones o

ayudas mediante las cuales el docente interactúa con el alumnado para facilitar

su aprendizaje (Tharp & Gallimore, 1989). El

presente estudio se centra en la concreción que realizan van de Pol et al.

(2010; 2011) del tipo de ayudas

pedagógicas que pueden implementarse en el aula de ciencias: preguntas, feedback, pistas, instrucciones, explicaciones, modelado

verbal o no verbal del proceso u otras comunicaciones aclaratorias.

Sin embargo, en nuestro

contexto inmediato la indagación sigue siendo una metodología escasamente

implementada en comparación con otras actividades más tradicionales.

García-Carmona et al., (2017) ya discuten la necesidad de impulsar estrategias

formativas en la formación de los futuros docentes de educación primaria para

promover dicha metodología. Introducir las diferentes habilidades científicas

en la formación inicial puede ayudar a los DFI con poca experiencia indagadora

a iniciarse en el desarrollo de procesos investigadores. Diferentes estudios

destacan la importancia de dichas habilidades puesto que facilitan la

estructuración de una tarea indagadora al dividirla en subtareas más manejables

(Durmaz & Mutlu, 2016; Lazonder & Egberink, 2014).

1.2. El videoanálisis

para promover la indagación científica en los DFI

Atendiendo a las

aportaciones publicadas hasta el momento en otras disciplinas (Alles et al.,

2019), el videoanálisis de eventos docentes puede dar

respuesta a las necesidades formativas que presentan los DFI. En esta línea, se

atisban sus potencialidades para el análisis didáctico y la reflexión sobre

actividades de enseñanza y aprendizaje de las ciencias (Chan et al., 2020; Criswell et al., 2022; Luna, 2018; Roth et al., 2019; Zummo et al., 2021). Por ejemplo, los programas de

formación de desarrollo profesional basados en vídeos, como el de Science Teachers Learning From Lesson

Analysis (STeLLA), destacan

cómo la observación de episodios de enseñanza ejemplares fomenta el desarrollo

profesional en el periodo de formación inicial. Específicamente, se constatan

mejoras en el conocimiento de los DFI sobre los contenidos científicos que se

presentan en estos vídeos, sobre la pedagogía necesaria para implementarlos en

la práctica y cómo este conocimiento repercute positivamente en el aprendizaje

del alumnado de educación primaria (Roth et al., 2019). En una línea similar,

McDonald et al. (2019) describen el desarrollo de un seminario en el que los

DFI participan en la identificación y argumentación de aspectos clave de la

indagación científica a través del análisis de representaciones de prácticas

docentes. Esta formación ayuda a promover la visión profesional de los DFI, su

capacidad de reflexión y el conocimiento sobre la metodología de indagación.

Vogt y Schmiemann (2020) también destacan las

dificultades que los DFI presentan para implementar actividades indagadoras en

el aula y, por ello, cómo el videoanálisis beneficia

el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje de dicha metodología sin la presión de

actuar.

En síntesis, el videoanálisis se ha empleado eficazmente para promover la

reflexión y fomentar el conocimiento sobre la metodología de enseñanza-aprendizaje

de las ciencias a través de la indagación. Aunque se ha especulado sobre las

posibilidades y beneficios del videoanálisis en la

práctica docente, no se dispone de literatura que proporcione evidencia sobre

su eficacia formativa en la implementación de las habilidades científicas en el

aula de educación primaria.

Este estudio presenta un

proceso formativo centrado en el videoanálisis y su

impacto en la práctica docente de indagación científica de los DFI. Para ello,

se plantean dos preguntas de investigación:

1. ¿Qué habilidades científicas y ayudas

pedagógicas identifican los DFI en el videoanálisis

de una práctica educativa de referencia sobre indagación?

2. ¿Qué habilidades científicas y ayudas

pedagógicas movilizan los DFI en una clase de indagación en el aula escolar

antes y después del proceso formativo centrado en el videoanálisis?

2.

Metodología

2.1. Participantes

En este estudio pre-experimental la muestra no aleatoria se conformó por 51

DFI (76.5% mujeres; edad media entre 20 y 22 años) de una universidad del

noreste de España. Los DFI cumplían los siguientes criterios de selección: (1)

estar matriculados en el curso 2019-2020, (2) ser estudiantes de tercer año del

Grado de Educación Primaria y, (3) realizar el grado en modalidad dual. Cabe

especificar que los DFI en modalidad dual realizan, de 1º a 4º curso del grado,

el 40% de las horas totales de formación presencial en las escuelas. En

concreto, los DFI que conformaron la muestra asistían a escuelas urbanas

ubicadas en contextos socioeconómicos desfavorecidos.

Con la irrupción de la

pandemia COVID-19 y el cierre de los centros educativos algunos estudiantes no

realizaron la entrega del segundo registro audiovisual, lo que supuso una

reducción de la muestra a 30 participantes. Por lo tanto, solo se incluyeron

los DFI que completaron las distintas evidencias planteadas en el diseño de la

investigación: los registros audiovisuales en las escuelas y la tarea de videoanálisis en la universidad.

2.2. Proceso formativo de

los DFI

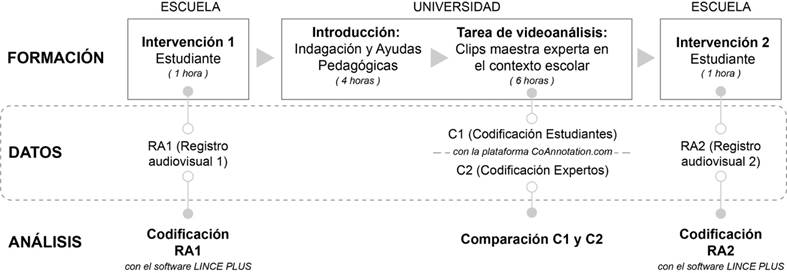

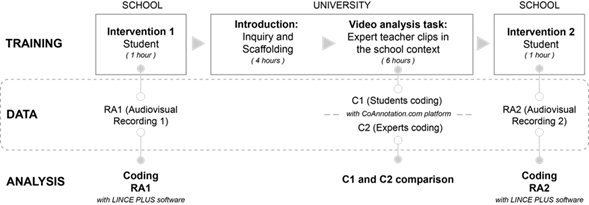

El proceso formativo se

estructura en 4 fases (Figura 1):

1. Intervención

1. Antes de la formación, los DFI

desarrollaron una intervención del ámbito científico en la escuela donde

realizaban sus prácticas. Esta práctica se grabó en vídeo y se entregó como el

Registro Audiovisual 1 (RA1).

2. Introducción. Los DFI participaron en una formación

sobre la didáctica de la indagación en la asignatura “Aprendizaje de las Ciencias

Experimentales”. Primero, se introdujo a los DFI las características generales

de las habilidades científicas y su implementación mediante el uso de ayudas

pedagógicas. A continuación, se presentó la tarea de videoanálisis

a los DFI, introduciendo las pautas de observación y análisis, así como la

plataforma CoAnnotation.com donde realizar dicha actividad (Cebrián-Robles,

2022).

Los

DFI analizaron un conjunto de nueve clips, de una duración de entre dos y cinco

minutos, seleccionados de una sesión grabada en vídeo del museo de ciencias Exploratorium (2021) en el que se muestra una indagación

científica de referencia realizada en una aula de

educación primaria por una maestra experta. Tres expertos investigadores en

didáctica de las ciencias y en didáctica y organización escolar (Coiduras et al., 2020; Peguera-Carré et al., 2021; Solé-Llussà et al., 2020), acordaron la selección de los clips,

considerando los principios heurísticos sobre el uso del vídeo en la enseñanza

de los DFI (Blomberg et al., 2013). Los nueve clips seleccionados fueron

evaluados como representativos de un proceso de indagación, mostrando la

implementación de las diferentes habilidades científicas acompañadas de las

ayudas pedagógicas. Se añadieron subtítulos en español al vídeo para evitar las

posibles dificultades para analizar adecuadamente su contenido.

3. Tarea

de videoanálisis (C1). Los DFI realizaron el videoanálisis en línea con la plataforma CoAnnotation.com.

Teniendo a Goodwin (1994, 2015) y Sherin y van Es

(2005) como referentes, se pidió a los DFI que: a) vieran el clip, b) se

fijaran en el inicio y el final de una secuencia (unidad de análisis) en la que

habrían de identificar una habilidad científica y/o ayuda pedagógica que la

docente implementaba, c) codificaran estas unidades con la habilidad (Durmaz & Mutlu, 2016; Özgelen, 2012; Rönnebeck et al.,

2016) y/o la ayuda identificada (van de Pol et al., 2011), d) interpretaran y

argumentaran las habilidades y ayudas advertidas (McDonald et al., 2019).

Posteriormente se re-visualizaron los vídeos en el

aula universitaria para comentar conjuntamente con la

docente universitaria las identificaciones e interpretaciones de las

habilidades científicas y las ayudas pedagógicas.

4. Intervención

2. Los DFI realizaron una nueva intervención

de indagación científica en la escuela durante sus prácticas, la grabaron en

vídeo y la entregaron como Registro Audiovisual 2 (RA2).

Figura 1

Relación

entre el proceso formativo, la recogida y el análisis de los datos.

2.3. Recogida y tratamiento

de la información

Se utilizó la metodología observacional

para analizar la conducta y eventos espontáneos (Anguera et al., 2020) en la

práctica docente mediante un instrumento bidimensional que incluye las

habilidades científicas (Durmaz & Mutlu, 2016; Özgelen, 2012; Rönnebeck et al., 2016) y las ayudas pedagógicas (van de

Pol et al., 2011).

2.3.1. Comparación de la tarea de videoanálisis de los estudiantes con la codificación de los

expertos

Tres expertos analizaron

inicialmente los nueve clips seleccionados (fase 2 del proceso formativo).

Primero, segmentaron los clips en unidades de análisis según los siguientes

criterios: (1) en cada unidad se representaba al menos una habilidad científica

y/o una ayuda pedagógica, y (2) cada unidad seguía una misma línea de lógica y

significado (Krippendorf, 2019). Por ejemplo, dos o

más unidades consecutivas podían incluir la misma habilidad científica, y aun

así no podían ser unificadas, ya que cada una tenía su propio significado. A

continuación, los expertos codificaron las habilidades científicas y las ayudas

pedagógicas expuestas en cada unidad de análisis. Tras un proceso iterativo se

obtuvo un kappa de Cohen de .87 entre los tres

expertos (Cohen, 1960). Se realizó una última iteración con el fin de alcanzar

un consenso total.

Para dar respuesta a la

primera pregunta de investigación se realizó una comparación midiendo la

frecuencia de acuerdo entre los resultados de la observación de los DFI durante

su tarea de videoanálisis (C1) y el análisis de los

expertos (C2).

2.3.2. Análisis de los registros

audiovisuales 1 y 2

Con el consentimiento

informado y los derechos de imagen de los estudiantes universitarios, de las

escuelas y del alumnado escolar, los DFI fueron grabados en vídeo mientras

desarrollaban sus sesiones de ciencias indagadoras en el aula escolar antes y

después de participar en el proceso formativo (Figura 1). Los 30 DFI incluidos

en la muestra cumplieron los criterios de inclusión específicos: a)

participación en todo el proceso formativo, b) entrega del registro audiovisual

1 y 2, c) condiciones técnicas suficientes de imagen y sonido para la

identificación correcta de la conducta docente en RA1 y RA2, d) incorporación

de una o más habilidades científicas y ayudas pedagógicas en las entregas de

vídeos mencionadas.

El análisis de los registros

audiovisuales se realizó mediante un diseño observacional (Anguera et al.,

2011): a) nomotético, al observar las

intervenciones de 30 DFI considerándolos como una individualidad; b) dinámico, al hacer un seguimiento

analizando una intervención indagadora inicial (RA1) y otra final (RA2); y c) multidimensional, por proponer el

análisis de dos dimensiones relevantes en las intervenciones, habilidades

científicas y ayudas pedagógicas, reflejadas en una multiplicidad de

categorías. La codificación de RA1 y RA2 se llevó a cabo con el software libre

LINCE PLUS (Soto et al., 2021), que permitió introducir de forma integrada y

sincrónica en la pantalla del ordenador: a) las dimensiones y categorías del

instrumento de observación, b) los registros audiovisuales de las intervenciones,

y c) los resultados de la codificación. Este software también permite verificar

el control de calidad del dato basado en la concordancia interobservador

(Kappa).

Después de obtener las

imágenes de las intervenciones se procedió al entrenamiento de los expertos y a

la obtención del coeficiente de concordancia Kappa de Cohen (Cohen, 1960). En

todas las categorías del sistema los expertos alcanzaron unos valores de

fiabilidad interobservador de .82 para las

habilidades científicas y del .86 para las ayudas pedagógicas. Se realizó una

última fase de entrenamiento con el fin de discutir los desacuerdos y alcanzar

un consenso. Posteriormente se analizaron los 60 vídeos de los DFI.

Finalmente, atendiendo a la

segunda pregunta de investigación se analizó la distribución de las habilidades

científicas y las ayudas pedagógicas identificadas en Microsoft Excel 16.16.2

para obtener una imagen inicial de las tendencias de los datos. A continuación,

se realizó un análisis para identificar patrones temporales entre las acciones

de los DFI en RA1 y RA2. Magnusson (2000) señaló que el método de análisis de

T-patterns se basa en el supuesto que los

comportamientos humanos complejos tienen una estructura temporal que no puede

detectarse completamente con la observación u otra lógica estadística

cuantitativa. Así, este tipo de análisis se centra en medidas repetidas e

intensivas para detectar patrones de comportamiento recurrentes sincrónicos y

secuenciales (Magnusson, 2000; Moskowitz et al.,

2009). Los T-patterns son secuencias de eventos

caracterizados por restricciones estadísticamente significativas dentro de una

ventana de tiempo (intervalo crítico). Mediante la detección de estos patrones

temporales se pueden identificar analogías estructurales a través de diferentes

niveles de organización, hecho que representa un cambio importante del análisis

cuantitativo al estructural (Santoyo et al., 2020). El análisis de T-patterns se llevó a cabo en THEME v.6 y, en este estudio,

se aplicaron los siguientes filtros: a) frecuencia de ocurrencia igual o

superior a 3; b) nivel de significación de < .005, y c) ajuste de reducción

de redundancia del 90% para ocurrencias de patrones similares.

3. Análisis y resultados

Respecto a la primera

pregunta de investigación se compara el videoanálisis

realizado por los expertos (C1) con el de los DFI (C2). La Tabla 1 muestra la

frecuencia de acuerdo (f) que indica

el porcentaje de DFI que coinciden con los expertos en la codificación de las

habilidades científicas y de las ayudas pedagógicas. La concordancia solamente

se consideró cuando la codificación de los DFI y de los expertos coincidía en

al menos un 80% de la unidad de análisis. En la comparación de C1 y C2 se

observa:

En cuanto a las habilidades científicas, una mayor

coincidencia en las identificaciones de los DFI de: a) Comunicar, con valores del 90% al 97% de acuerdo; b) Interpretar, con frecuencias alrededor

del 70%; c) Planificar y Experimentar,

con valores mayoritariamente superiores al 50%.

En las ayudas pedagógicas se

observa una gran coincidencia en todas ellas, destacando: a) las Preguntas y las Instrucciones, con

frecuencias de hasta el 100% de acuerdo; b) el Feedback, con frecuencias de hasta el 97%; c) las Pistas, con valores igual o superiores al 70%.

Tabla 1

Acuerdo

de la codificación de los DFI con los expertos en el videoanálisis.

Observar: OBS

/Pregunta de investigación: PRI /Predicciones: PDC /Hipótesis: HIP /Planificar

y experimentar: PLA /Interpretar: INT /Comunicar: COM /Feedback:

FDB /Pistas: PST /Instrucciones: INS /Explicaciones: EXP/ Modelos: MOD

/Preguntas: PRE /Otras: OTR

Con relación a la segunda

pregunta de investigación, la Tabla 2 presenta una comparación de la frecuencia

con la que los DFI implementan unas y otras en sus intervenciones en el aula

antes (RA1) y después (RA2) de la formación recibida (Figura 1). La Tabla 2

muestra la frecuencia relativa las habilidades científicas y ayudas pedagógicas

identificadas en RA1 y RA2 con respecto al número total de unidades de análisis

detectadas, siendo estas n(RA1)=3512 y n(RA2)=3009.

El cambio existente entre RA1 y RA2 evidencia un incremento en la frecuencia de

implementación de las habilidades científicas y una frecuencia similar en el

uso de las ayudas pedagógicas.

Tabla 2

Estadística

descriptiva de habilidades científicas y ayudas pedagógicas

|

Habilidad científica |

f relativa

(%) |

|

Ayuda

pedagógica |

f relativa

(%) |

||

|

RA1 |

RA2 |

|

RA1 |

RA2 |

||

|

Observar |

2.8 |

9.4 |

Feedback |

13.3 |

16.1 |

|

|

Pregunta

de investigación |

1.5 |

5 |

Pistas |

4.3 |

4.6 |

|

|

Predicciones |

1.7 |

9.1 |

Instrucciones |

13.3 |

12.2 |

|

|

Hipótesis |

.9 |

6 |

Explicaciones |

8.5 |

7.5 |

|

|

Planificar

y experimentar |

16.1 |

19.9 |

Modelos |

1.8 |

2.2 |

|

|

Interpretar |

.7 |

6.8 |

Preguntas |

41.3 |

39.1 |

|

|

Comunicar |

1 |

3.7 |

Otras |

3.9 |

3.4 |

|

También se estudia la

aparición simultánea de habilidades científicas junto a ayudas pedagógicas. En

la Tabla 3 se presenta la frecuencia relativa de dichos eventos simultáneos,

puesto que esta frecuencia permite comparar dos sucesos con valores distintos,

como son las unidades de análisis totales en RA1 y RA2. Se destacan con

sombreado gris los eventos simultáneos con una frecuencia relativa igual o

superior al 1%, dado el elevado número de unidades de análisis en RA1 y RA2.

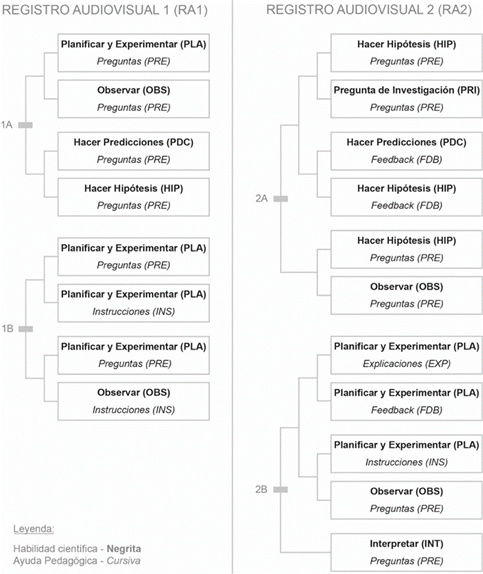

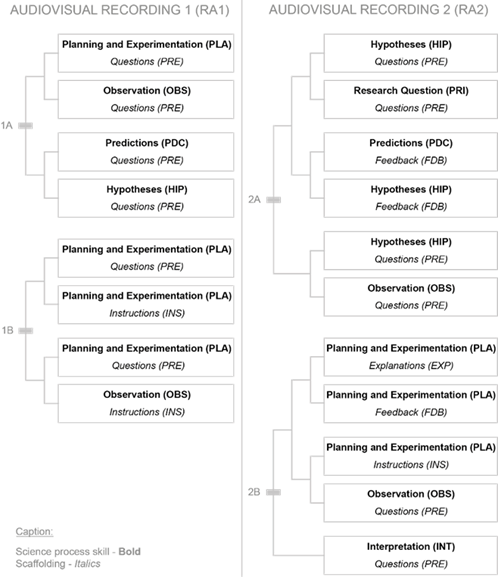

En la Figura 2 se presentan dendrogramas de T-patterns entre

habilidades científicas que implementan los DFI y ayudas pedagógicas con las

que las acompañan en RA1 y RA2. La figura ejemplifica secuencias de eventos

caracterizados por vínculos estadísticamente significativos entre la habilidad

científica implementada en el aula (en negrita en la figura) mediante la ayuda

pedagógica (en cursiva en la figura) dentro de un intervalo crítico determinado

(Magnusson, 2000).

Los eventos simultáneos

destacados en la Tabla 3 y los T-patterns de la Figura

2 muestran coherencia. En RA1 destaca la implementación de patrones simples y

repetitivos principalmente de las habilidades de Observación y Planificación y

Experimentación que acompañan con Instrucciones

y Preguntas. En cambio, las eventos

simultáneos y patrones de conducta aumentan en número y diversidad en RA2. Los

resultados constatan que las Preguntas

siguen siendo la ayuda pedagógica más utilizada por los DFI, aunque en RA2

acompaña a todas las habilidades científicas. Además, se observan diversos

eventos simultáneos que incluyen la Observación

acompañada de Feedback

y Explicaciones, la Planificación y Experimentación

acompañada de Feedback, Instrucciones, Explicaciones y Modelos, y la formulación de Hipótesis y Predicciones y la Interpretación

de los resultados acompañada de Feedback. En RA2, los patrones de conductas detectados

sugieren que la formulación de Hipótesis

y Predicciones va acompañada de la Pregunta de Investigación; esta conducta

predice la aparición de las habilidades de Observación,

Planificación y Experimentación e Interpretación.

Tabla 3

Frecuencia

relativa entre la aparición simultánea de habilidades científicas y ayudas

pedagógicas que los DFI implementan en sus prácticas indagadoras RA1 y RA2

|

f relativa

(%) |

Código |

Registro audiovisual |

Ayudas pedagógicas |

||||||

|

FDB |

PST |

INS |

EXP |

MOD |

PRE |

OTR |

|||

|

Habilidades científicas |

OBS |

RA1 |

.3 |

.1 |

.3 |

.3 |

.3 |

1.4 |

0 |

|

RA2 |

1.6 |

.3 |

.6 |

1 |

.4 |

4.9 |

.3 |

||

|

PRI |

RA1 |

0 |

.1 |

.3 |

0 |

0 |

.9 |

.2 |

|

|

RA2 |

.5 |

.3 |

.5 |

.5 |

0 |

3 |

.1 |

||

|

PDC |

RA1 |

0 |

0 |

.2 |

.1 |

0 |

1.1 |

0 |

|

|

RA2 |

1.4 |

.4 |

.7 |

.8 |

.2 |

5.5 |

.1 |

||

|

HIP |

RA1 |

.1 |

0 |

.1 |

.1 |

0 |

.5 |

0 |

|

|

RA2 |

1.9 |

.1 |

.4 |

.3 |

.2 |

3 |

.1 |

||

|

PLA |

RA1 |

1.6 |

.2 |

4.5 |

1.4 |

.4 |

5.2 |

.1 |

|

|

RA2 |

3.9 |

.5 |

6.4 |

1.8 |

1.1 |

5.3 |

.1 |

||

|

INT |

RA1 |

.1 |

.1 |

0 |

.1 |

0 |

.5 |

0 |

|

|

RA2 |

1.1 |

.6 |

.2 |

.8 |

.3 |

3.6 |

.1 |

||

|

COM |

RA1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.5 |

.1 |

|

|

RA2 |

.5 |

.1 |

.3 |

.4 |

0 |

2.4 |

.1 |

||

Observar: OBS

/Pregunta de investigación: PRI /Predicciones: PDC /Hipótesis: HIP /Planificar

y experimentar: PLA /Interpretar: INT /Comunicar: COM /Feedback:

FDB /Pistas: PST /Instrucciones: INS /Explicaciones: EXP/ Modelos: MOD

/Preguntas: PRE /Otras: OTR

Figura 2

Dendrogramas de T-patterns entre

habilidades científicas y ayudas pedagógicas que los DFI implementan en la

escuela en RA1 y RA2.

4. Discusión

y conclusiones

La indagación científica todavía

presenta una incipiente implementación en el aula de educación primaria,

traduciéndose en un escenario con escasas oportunidades de experimentación para

los DFI (García‐Carmona

et al., 2017), además de su bajo conocimiento y dominio de las habilidades

científicas (Nilsson & Loughran, 2012). En este

estudio, los resultados muestran la eficacia del proceso formativo centrado en

el videoanálisis para compensar dichas

circunstancias. A continuación, se responde a las dos preguntas de

investigación planteadas.

Tras recibir una formación

teórica inicial, los DFI fueron capaces de identificar, de forma similar a los

expertos, tanto las distintas habilidades científicas características de un

proceso indagador como las ayudas pedagógicas en el videoanálisis

de una práctica docente de referencia. Con relación a estos resultados se

destacan los siguientes aspectos (Tabla 1): a) un gran acuerdo de los DFI con

los expertos especialmente destacado en la identificación de la Planificación y Experimentación, habilidad

científica también, con una mayor implementación en el RA1; b) una baja

implementación de las habilidades Pregunta

de Investigación e Interpretación

en RA1, que contrasta con una alta identificación de estas en el videoanálisis y una implementación más frecuente en RA2.

Estas identificaciones permiten afirmar que el proceso formativo centrado en el

videoanálisis ha facilitado la transferencia de la

teoría a la práctica de las habilidades científicas y las ayudas pedagógicas al

aula de educación primaria (García-Fernández & Benítez-Roca, 2000; Gaudin & Chaliès, 2015;

Richards et al., 2021). Probablemente, el uso de herramientas en línea de

observación en vídeo ha contribuido a la alta convergencia en las

identificaciones (Blikstad-Balas & Sørvik, 2015; Jewitt, 2012).

Dichas herramientas permiten reproducir, pausar y revisualizar

las secuencias, hecho que ha podido conllevar una mejor comprensión y

asimilación del conocimiento pedagógico asociado a la metodología de indagación

(Klette & Blikstad-Balas,

2018).

El estudio de las

intervenciones de los DFI en el aula, antes de la formación (RA1), permite

caracterizarlas como más cercanas a la demostración científica y a la

introducción de contenidos desde una perspectiva principalmente teórica (García‐Carmona et al., 2017; Solé-Llussà et al., 2018). Esto es congruente con los T-patterns obtenidos en RA1 en los que se observa la

repetición casi en exclusiva de las habilidades Observación y Planificación y

Experimentación (Figura 2). En RA2, destaca la transición de modelos más

tradicionales hacia la indagación incorporando las distintas habilidades

científicas. Se observan patrones de conductas de los DFI más complejos, con un

incremento notable en la frecuencia y diversidad de las diferentes habilidades

científicas (Tabla 2). Los T-patterns también

muestran que los DFI introducen secuencias indagadoras similares a las que han

observado en los vídeos analizados durante el proceso formativo, extrapolando

las acciones observadas de la maestra experta a su propia práctica docente.

Esto sugiere una función modelizante del vídeo

promoviendo la transferibilidad al aula escolar (Roth et al., 2019; Zaragoza et

al., 2021).

En cuanto al uso de las ayudas

pedagógicas no se observan cambios entre RA1 y RA2, lo que indica que estas se

siguen implementando en un número y diversidad similar. Sin embargo, en RA2,

las ayudas implementadas están mucho más asociadas al desarrollo de habilidades

científicas para favorecer la indagación. Destacan, especialmente, Preguntas y Feedback como las ayudas que

mayor simultaneidad presentan con el conjunto de habilidades científicas

implementadas (Tabla 3). Esto puede explicarse por su pertinencia al contenido

pedagógico general y no específico, así como por su utilidad en la promoción de

la participación desde la comunicación, y como medio para monitorizar la

comprensión del alumnado (van de Pol et al., 2011). Planificación y Experimentación es la habilidad más frecuente en

las intervenciones que los DFI realizan en el aula y en la que se implementan

una mayor diversidad de ayudas (Tabla 2 y Tabla 3). Por un lado, se trata de

una habilidad que requiere del alumnado escolar una importante carga cognitiva

y es posible que esto motive un uso más frecuente y diverso de las ayudas

pedagógicas por parte de los DFI (Kruit et al., 2018;

Rönnebeck et al., 2016). Por otro lado, esta

situación puede considerarse como ejemplo de la función modelizante

del vídeo de la maestra experta, en el que se observa la relevancia de la

planificación y la necesidad de acompañarla de un conjunto variado de ayudas

pedagógicas. De este hecho se deriva la trascendencia de proporcionar modelos

de referencia durante la formación inicial que recojan la integridad y la

complejidad de la actuación docente.

Entre las limitaciones de

este estudio señalamos la muestra reducida y su selección no probabilística,

dado que se centra en un grupo concreto de estudiantes en formación dual.

Además, en el escenario de pandemia, el cierre temporal de las escuelas

dificultó la recogida de datos disminuyendo los participantes y reduciendo la

posibilidad de generalización de resultados. Aun así, la investigación tiene

valor exploratorio y descriptivo como estudio observacional en la formación

sobre indagación científica de los DFI, considerando las escasas aportaciones

en este ámbito. En esta línea se plantea la necesidad de realizar una iteración

incorporando un grupo control para llegar a una comparación estadística del impacto

formativo del diseño. Así, como proponen Blomberg et al. (2013), en próximos

trabajos parece necesario una mayor diversidad de videos donde se representen

las distintas habilidades científicas, con una presencia suficiente para su

identificación y análisis a lo largo de las intervenciones. También se propone

el diseño y validación de instrumentos para el videoanálisis,

favoreciendo un mayor nivel de acuerdo de los observadores.

Finalmente, los resultados

de este estudio y las posibles líneas de continuidad pueden formar parte de la

respuesta a las necesidades formativas en la pedagogía de las ciencias que se

han reportado en la literatura y los informes internacionales.

5. Agradecimientos

Los autores agradecen a los

directores de los centros, a los maestros, a las familias y al alumnado, así

como a los maestros en formación inicial, su disposición a participar y las

autorizaciones para la recolección de los datos en las aulas.

6.

Financiación

Esta investigación se

realizó dentro del Grupo de Investigación Competencias, Tecnologías y Sociedad

en Educación (COMPETECS, 2021 SGR 01360). Los autores agradecen el apoyo

recibido de 2020 ARMIF 00019 de la Agència d’Ajuts per a la Rercerca i Universitats (AGAUR) y del Departament

d’Economia i Societat del Coneixement de Cataluña, así como la ayuda de la Universitat de Lleida en el Programa de Promoción de la

Investigación 2019. Además, este artículo de investigación ha recibido una beca

para su revisión lingüística del Instituto de la Lengua de la Universidad de Lleida

(convocatoria 2023).

Video analysis of scientific inquiry in preservice

teacher education: Identification of T-patterns

1. Introduction

The present study shows how the

observation of teaching events promotes theory-practice transfer and the

transmission of pedagogical knowledge in initial teacher training (Zaragoza et

al., 2021). These observations have been supported by video, in line with its

increasing use in formal education (Alpert & Hodkinson, 2019; Pattier & Ferreira, 2022). The audiovisual

material allows access to authentic classroom situations to select excerpts of

reference teaching actions. The analysis of relevant events enables Preservice

Teachers (PTs) to build discipline-specific knowledge, promote reflection, and

more effectively and engage creatively in their teaching practice (Gaudin &

Chaliès, 2015; Richards et al., 2021). Sherin et al.

(2011) and Goodwin (1994) claim that video analysis allows selectively

addressing relevant in-class events in order to

identify and argue the observed events and associate them with concepts and

theories. Colomo-Magaña et al. (2020) highlight that combining these

observation practices with audiovisual resources

helps to invigorate a training process for a generation that is a regular

prosumer in the socio-personal environment. Additionally, the use of video

provides flexibility and encourages the autonomy and self-regulation of the PTs

during their learning process.

This investigation is

conducted in the field of experimental sciences and, in

particular, in the use of video analysis to promote scientific inquiry

practices among primary school PTs.

1.1. The development of

scientific inquiry practices in primary education

International education

standards emphasise the importance of implementing inquiry-based learning

methodologies in experimental sciences education (National Research Council,

2012; Pedaste et al., 2015). This methodology can be

understood as the instructional transposition of research

and it consists of the ability to plan and carry out experimental designs that

enable learners to answer questions and solve problems (Harlen, 2013).

Firstly, inquiry implies

developing a set of science process

skills, which are understood as activities that reflect real tasks

performed by scientists. These involve the ability to apply rules or principles

in the design and execution of a scientific investigation (Harlen &

Qualter, 2009). Durmaz and Mutlu (2016), Özgelen

(2012) and Rönnebeck et al. (2016), in a summary

proposal, list and define the following science

process skills of an inquiry process: observing, questioning,

hypothesising, designing an investigation with control variables, interpreting and communicating.

Secondly, as in any teaching

process, the deployment of the different scientific skills in the classroom

also entails the presence of some actions or scaffolds by means of which the

teacher interacts with the pupils to facilitate their learning (Tharp & Gallimore,

1989). The present study focuses on the categorisation provided by van de Pol

et al. (2010; 2011) of the type of scaffolds that can be used in a science

classroom: questions, feedback, hints, instructions, explanations, verbal or

non-verbal models of the process or other explanatory communications.

However, within our immediate

context, inquiry is still a scarcely implemented methodology in comparison with

other, more traditional activities. García-Carmona et al. (2017) discussed the

need to promote educational strategies in the training of prospective primary

school teachers to encourage this methodology. Introducing different science

process skills to initial training could help PTs with limited inquiry

experience to start developing inquiry processes. Different studies highlight

the importance of these skills as they support the organisation of an inquiry

task by splitting it into more manageable sub-tasks (Durmaz & Mutlu, 2016, Lazonder & Egberink, 2014).

1.2. Video analysis to promote

scientific inquiry in PTs

Considering the contributions

published to date in other disciplines (Alles et al., 2019), video analysis of

teaching events can address PTs' training needs.

Thus, its potential for instructional analysis and reflection on science

teaching and learning activities can be envisaged (Chan et al., 2020; Criswell

et al., 2022; Luna, 2018; Roth et al., 2019; Zummo et al., 2021). For example,

video-based professional development training programmes, such as Science

Teachers Learning From Lesson Analysis (STeLLA), highlight how the observation of exemplary

teaching episodes promotes professional development in initial teacher

education. More specifically, an improvement is noted in PTs'

knowledge of the scientific content provided in these videos, the pedagogy

needed to implement it in practice, and how this knowledge has a positive

impact on primary education pupils' learning (Roth et al., 2019). Similarly,

McDonald et al. (2019) describe the development of a seminar in which PTs

participate in the identification and argumentation of key aspects of

scientific inquiry through the analysis of representations of teaching

practices. This training helps to promote PTs'

professional vision, their reflective capacity and

their knowledge of the inquiry methodology. Vogt and Schmiemann

(2020) also highlight the difficulties that PTs have in conducting scientific

inquiry activities in the classroom and, therefore, how video analysis benefits

the teaching-learning process of such a methodology without the pressure to act.

In summary, video analysis has

been effectively used to promote reflection and foster knowledge about the

scientific inquiry teaching-learning methodology. Although there has been

speculation about the possibilities and benefits of video analysis for teaching

practice, there is no evidence in the literature of its formative effectiveness

in the implementation of science process skills in the primary school

classroom.

This study introduces a

training process centred on video analysis and its impact on PTs' scientific inquiry teaching practices. With this

purpose, two research questions are posed:

1.

What science process skills

and scaffolds do PTs identify in the video analysis of an educational reference

practice on scientific inquiry?

2.

What science process skills

and scaffolds do PTs use in an inquiry lesson in a school classroom before and

after the training process centred on video analysis?

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

In this pre-experimental

study, the non-randomised sample included 51 PTs (76.5% female; mean age

between 20 and 22 years) from a university located in the northeast of Spain.

The PTs met the following selection criteria: (1) be enrolled in the 2019-2020

academic year, (2) be third-year students of the Primary Education Degree, and

(3) follow the degree programme in a dual-system. It should be specified that

from the 1st to the 4th year of the degree, the PTs in dual training perform

40% of the total hours of face-to-face training in schools. Specifically,

during the training process the PTs of the sample attended urban schools

located in disadvantaged socio-economic contexts.

With the outbreak of the COVID-19

pandemic and the closure of educational centres, some of the students did not

submit the second audiovisual recording, which meant

a reduction of the sample to 30 participants. Therefore, only the PTs that

completed the different pieces of evidence proposed in the research design were

included. The evidence consisted of the audiovisual

recordings performed at schools and the video analysis task at the university.

2.2. PTs’

training process

The training process is

organised in 4 stages (Figure 1):

1.

Intervention 1. Before the training, the PTs

carried out a scientific intervention in the school where they were doing their

internships. This was recorded on video and delivered as Audiovisual

Recording 1 (RA1).

2. Introduction. The PTs attended a training process on

inquiry instruction within the subject "Experimental Science

Learning". First, the PTs were introduced to the general characteristics

of science process skills and their use with scaffolds. Then, the video

analysis task was explained to the PTs, introducing the observation and

analysis guidelines, as well as the CoAnnotation.com platform where this

activity was performed (Cebrián-Robles, 2022).

The PTs analysed a set of nine clips of

between two and five minutes in duration, selected from a video-recorded

session of the Exploratorium science museum (2021). This lecture was managed by

an expert teacher in an elementary school classroom, showing an exemplary

scientific inquiry. Three expert researchers in science learning and school

instruction and organisation (Coiduras et al., 2020; Peguera-Carré et al., 2021; Solé-Llussà

et al., 2020), agreed on the selection of these clips, considering the

heuristic principles for the use of videos in the PTs'

training (Blomberg et al., 2013). The nine selected clips were evaluated as

being representative of an inquiry process, showing the implementation of the

different science process skills together with the scaffolds. Spanish subtitles

were added to the video to avoid possible limitations in properly analysing the

content.

3.

Video analysis task (C1). The PTs performed the

online video analysis using the CoAnnotation.com platform. Taking Goodwin

(1994, 2015) and Sherin and van Es (2005) as referents, the PTs were asked to:

a) watch the clip, b) look at the beginning and end of a sequence (unit of

analysis) in which they should identify a science process skill and/or a

scaffolding means implemented by the teacher, c) code these units with the

skill (Durmaz & Mutlu, 2016; Özgelen, 2012; Rönnebeck et al., 2016) and/or the scaffolding means (van

de Pol et al., 2011), d) interpret and argue the skills and scaffolds coded

(McDonald et al., 2019). Afterwards, the videos were re-visualised in the

university classroom to discuss together with the university lecturer the identification

and argumentation of the science process skills and the scaffolding means.

4.

Intervention 2. The PTs conducted a new

scientific inquiry intervention at the school during their internship, recorded

it on video and submitted it as Audiovisual Recording

2 (RA2).

Figure 1

Links between the training

process and data collection and analysis

2.3. Data collection and

analysis

An observational methodology

was used to analyse behaviour and spontaneous events (Anguera et al., 2020) in

teaching practice using a two-dimensional instrument which includes the science

process skills (Durmaz & Mutlu, 2016; Özgelen,

2012; Rönnebeck et al., 2016) and the scaffolding

means (van de Pol et al., 2011).

2.3.1. Comparison of the students' video analysis task with the experts'

coding

Three experts initially

analysed the nine selected clips (stage 2 of the training process). First, they

divided the clips into units of analysis according to the following criteria:

(1) at least one science process skill and/or one scaffolding means was

represented in each unit, and (2) every unit followed a common logic and

meaning (Krippendorf, 2019). For instance, two or more successive units could

include the same science process skill, and yet they could not be unified, as

each had its own meaning. The experts then coded the science process skills and

the scaffolds observed in each unit of analysis. After an iterative process, a

Cohen's kappa of .87 was obtained among the three experts (Cohen, 1960). There

was a final iteration in order to reach full

consensus.

In order to answer the first research question, a comparison was made by measuring

the frequency of agreement between the results of the PTs'

observation during their video analysis task (C1) and the experts' analysis

(C2).

2.3.2. Analysis of audiovisual recordings 1

and 2

After informed consent and

image rights were obtained from PTs, schools and school pupils, the PTs were

video recorded as they performed their scientific inquiry lessons in the school

classroom before and after participating in the training process (Figure 1).

The 30 PTs included in the sample met the specific inclusion criteria: a)

participation in the whole training process, b) submission of audiovisual recordings 1 and 2, c) adequate technical

conditions of image and sound to correctly identify the teaching behaviour in

RA1 and RA2, and d) inclusion of one or more science process skills and

scaffolds in the aforementioned video submissions.

The audiovisual

recordings were analysed using an observational design (Anguera et al., 2011):

a) nomothetic, observing the

interventions of 30 PTs as an individuality; b) dynamic, following up by analysing an initial (RA1) and a final

(RA2) inquiry intervention; and c) multidimensional,

by proposing the analysis of two relevant dimensions in the interventions, the

science process skills and the scaffolds, which are reflected in a multiplicity

of categories. RA1 and RA2 were coded with the free LINCE PLUS software (Soto

et al., 2021), which allowed introducing the following in an integrated and

synchronous way on the computer screen: a) the dimensions and categories of the

observational instrument, b) the audiovisual

recordings of the interventions, and c) the coding results. This software also

enables verifying the data quality control based on inter-observer concordance

(Kappa).

After collecting the images of

the interventions, the experts were trained and Cohen's Kappa coefficient of

concordance was obtained (Cohen, 1960). In all the categories of the system,

the experts achieved inter-observer reliability values of .82 for the science

process skills and .86 for the scaffolds. A final training step was performed

to discuss disagreements and reach a consensus. Subsequently, the 60 PTs videos

were analysed.

Finally, addressing the second

research question, the distribution of the science process skills and the

scaffolding means identified was analysed using Microsoft Excel 16.16.2 to

provide an initial picture of the data trends. Next, an analysis was conducted

to identify T-patterns between PTs’ actions in RA1

and RA2. Magnusson (2000) stated that the T-patterns analysis method is based on the assumption that complex human behaviours

have a temporal structure that cannot be fully detected by observation or other

quantitative statistical logic. Thus, this type of analysis focuses on repeated

and intensive measurements to detect synchronous and sequential recurrent

behavioural patterns (Magnusson, 2000; Moskowitz et al., 2009). T-patterns are

sequences of events characterised by statistically significant restrictions

within a temporal interval (critical interval). By detecting these temporal

patterns, structural analogies can be identified across different levels of

organisation, which represents an important change from quantitative to

structural analysis (Santoyo et al., 2020). The analysis of T-patterns was

executed using THEME v.6 and, in this study, the following filters were

applied: a) frequency of occurrence equal to or greater than 3; b) significance

level of < .005, and c) redundancy reduction adjustment of 90% for

occurrences of similar patterns.

3. Analysis and results

Regarding the first research question,

the video analysis carried out by the experts (C1) is compared with that of the

PTs (C2). Table 1 shows the frequency of agreement (f) which represents the percentage of PTs who agree with the

experts in the coding of the science process skills and the scaffolding means.

Agreement was only considered when the coding of the PTs and the experts

coincided in at least 80% of the analysis unit. In comparing C1 and C2 the

following is observed:

Regarding science process

skills, there is a greater coincidence in the identification by PTs of: a) Communication, with values from 90% to

97% agreement; b) Interpretation,

with frequencies of around 70%; c) Planning

and Experimentation, with values mostly above 50%.

For scaffolding means, there

is a high degree of agreement in all of them, highlighting: a) Questions and Instructions, with

frequencies of up to 100% agreement; b) Feedback, with frequencies of up to 97%; and c) Hints, with values equal to or higher

than 70%.

Table 1

Coding agreement between PTs

and experts in the video analysis

|

Video

description |

Analysis unit

(duration) |

Science Process

Skills coded by the experts (f % PTs agreement) |

Scaffoldings

coded by the experts |

|

1. The teacher

supports pupils by asking questions and giving feedback to plan the inquiry

task step by step. |

1.1 (0’ 55’’) |

PLA (90) |

FDB (27) /PRE (100) |

|

2. The

teacher guides pupils using different scaffolding means to remind them of

scientific concepts and real-life experiences related to magnetism. |

2.1 (1’ 42’’) |

OBS (40) |

INS (40) /EXP (70) /MOD (87) /PRE (60) |

|

2.2 (1’ 04’’) |

OBS (7) |

FDB (80) /PRE (90) |

|

|

2.3 (0’ 33’’) |

OBS (7) |

FDB (33) /PRE (50) |

|

|

3. The teacher

provides explanations and instructions to help pupils formulate the research

question: "Is the block magnet stronger than the ring magnet?" |

3.1 (0’ 29’’) |

PRI (83) |

EXP (60) |

|

3.2 (0’ 30’’) |

PRI (67) |

INS (73) |

|

|

4. The pupils,

with the teacher's support, discuss the experimental design to ensure its

reliability, define the study variables, the required materials and how to

collect the data. |

4.1 (0’ 56’’) |

PLA (83) |

PST (70) /INS (100) /MOD (83) |

|

4.2 (0’ 42’’) |

PLA (70) |

FDB (13) /PRE (100) |

|

|

4.3 (0’ 52’’) |

PLA (60) |

FDB (33) /INS (90) /PRE (97) |

|

|

4.4 (0’ 50’’) |

PLA (50) |

FDB (23) /PRE (80) |

|

|

4.5 (0’ 33’’) |

PLA (43) |

MOD (67) /PRE (57) |

|

|

5. The teacher

organises the task by reminding pupils of the planning so that they can

self-manage. They discuss in the classroom, through questions and feedback,

what they expect to happen and they record the

results on a grid. |

5.1 (0’ 37’’) |

PLA (20) |

INS (70) /PRE (80) |

|

5.2 (0’ 06’’) |

PDC (33) |

PRE (77) |

|

|

5.3 (0’ 14’’) |

INT (77) |

FDB (50) /INS (63) /PRE (77) |

|

|

6. The

teacher guides the pupils to recall the research question and discuss the findings

using the evidence in search of scientific reasoning. E.g.

"the block magnet is stronger because the number of washers attached to

it is greater than in the ring magnet". |

6.1 (0’ 20’’) |

PRI (80) |

PRE (80) |

|

6.2 (0’ 27’’) |

INT (40) |

FDB (33) /INS (67) /PRE (100) |

|

|

6.3 (0’ 19’’) |

HIP (17) |

FDB (60) /PST (87) |

|

|

6.4 (0’ 54’’) |

INT (70) |

FDB (67) /PRE (40) |

|

|

6.5 (0’ 33’’) |

INT (63) |

FDB (63) /PRE (17) |

|

|

7. They share the collected data from the experimentation by means of a

graphic representation and by describing it. The teacher promotes discussion

with questions and aids understanding with explanations. |

7.1 (0’ 36’’) |

INT (63) |

INS (77) /EXP (53) |

|

7.2 (1’ 10’’) |

INT (87) |

FDB (67) /INS (83) /EXP (57) |

|

|

7.3 (0’ 31’’) |

INT (77) |

EXP (37) |

|

|

7.4 (0’ 32’’) |

INT (73) |

EXP (17) /PRE (57) |

|

|

8. They

analyse the graphic representation. The teacher assists the pupils to link

the empirical evidence with scientific concepts related to magnetism. |

8.1 (0’ 23’’) |

INT (60) |

MOD (23) /PRE (73) |

|

8.2 (1’ 32’’) |

INT (97) |

FDB (97) /PST (80) /PRE (97) |

|

|

8.3 (0’ 30’’) |

INT (80) |

FDB (63) |

|

|

8.4 (0’ 45’’) |

INT (77) |

FDB (50) |

|

|

9. The pupils,

working in pairs and following the teacher's instructions, record the

research question on a poster, along with the claims and evidence gathered. |

9.1 (0’ 34’’) |

COM (97) |

INS (60) /MOD (63) |

|

9.2 (0’ 12’’) |

PRI (17) |

INS (80) /MOD (50) |

|

|

9.3 (1’ 03’’) |

COM (90) |

INS (80) /MOD (43) |

|

|

9.4 (0’ 59’’) |

INT (50) |

FDB (47) /PST (77) /PRE (77) |

Observation: OBS /Research Question: PRI /Predictions: PDC /Hypotheses:

HIP /Planning and experimentation: PLA /Interpretation: INT /Communication: COM

/Feedback: FDB /Hints: PST /Instructions: INS /Explanations: EXP/ Models: MOD

/Questions: PRE /Others: OTR

Concerning the second research

question, Table 2 shows the frequency with which the PTs implemented both the

skills and the scaffolds in their interventions in the classroom before (RA1)

and after (RA2) the training process (Figure 1). Table 2 provides the relative

frequency of the science process skills and the scaffolding means identified in

RA1 and RA2 compared to the total number of units of analysis observed,

resulting in n(RA1)=3512

and n(RA2)=3009. The differences

between RA1 and RA2 demonstrate an increase in the frequency of implementation

of the science process skills and a similar frequency of the use of scaffolding

means.

The simultaneous observation of

science process skills together with scaffolding means is also studied. Table 3

shows the relative frequency of these simultaneous events, since this frequency

allows the comparison of two events with different values, as are the total

units of analysis in RA1 and RA2. Simultaneous events with a relative frequency

equal to or higher than 1% are shaded grey, considering the high number of

units of analysis in RA1 and RA2.

Figure 2 shows the T-patterns

dendrograms between the science process skills implemented by the PTs and the

teaching scaffolds supporting them in RA1 and RA2. The figure illustrates

sequences of events characterised by statistically significant associations

between the science process skill implemented in the classroom (in bold in the

figure) and the scaffolding means (in italics in the figure) within a given

critical interval (Magnusson, 2000).

The simultaneous events

highlighted in Table 3 and the T-patterns in Figure 2 show consistency. In RA1,

the implementation of simple and repetitive patterns stands out, mainly from

the skills of Observation and Planning and Experimentation accompanied

by Instructions and Questions. Conversely, the simultaneous

events and T-patterns increase both in number and diversity in RA2. The results

confirm that Questions remain the

scaffolding most used by PTs, although in RA2 it accompanies all the science

process skills. In addition, different simultaneous events are observed that

include Observation involving Feedback and Explanations, Planning and

Experimentation together with Feedback,

Instructions, Explanations and Models,

and the formulation of Hypotheses and

Predictions and the Interpretation of the results along with

Feedback. In RA2, the T-patterns

found suggest that the formulation of Hypotheses

and Predictions is associated with

the Research Question; this pattern

predicts the development of Observation,

Planning and Experimentation and Interpretation skills.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics of science

process skills and scaffolding means

|

Science process skills |

relative f (%) |

|

Scaffolding means |

relative f (%) |

||

|

RA1 |

RA2 |

|

RA1 |

RA2 |

||

|

Observation |

2.8 |

9.4 |

Feedback |

13.3 |

16.1 |

|

|

Research question |

1.5 |

5 |

Hints |

4.3 |

4.6 |

|

|

Predictions |

1.7 |

9.1 |

Instructions |

13.3 |

12.2 |

|

|

Hypotheses |

.9 |

6 |

Explanations |

8.5 |

7.5 |

|

|

Planning and experimentation |

16.1 |

19.9 |

Models |

1.8 |

2.2 |

|

|

Interpretation |

.7 |

6.8 |

Questions |

41.3 |

39.1 |

|

|

Communication |

1 |

3.7 |

Others |

3.9 |

3.4 |

|

Table 3

Relative frequency between the

simultaneous use of science process skills and scaffolding means implemented by

PTs in their RA1 and RA2 inquiry practices

|

relative f (%) |

Code |

Audiovisual recording |

Scaffolding

means |

||||||

|

FDB |

PST |

INS |

EXP |

MOD |

PRE |

OTR |

|||

|

Science

process skills |

OBS |

RA1 |

.3 |

.1 |

.3 |

.3 |

.3 |

1.4 |

0 |

|

RA2 |

1.6 |

.3 |

.6 |

1 |

.4 |

4.9 |

.3 |

||

|

PRI |

RA1 |

0 |

.1 |

.3 |

0 |

0 |

.9 |

.2 |

|

|

RA2 |

.5 |

.3 |

.5 |

.5 |

0 |

3 |

.1 |

||

|

PDC |

RA1 |

0 |

0 |

.2 |

.1 |

0 |

1.1 |

0 |

|

|

RA2 |

1.4 |

.4 |

.7 |

.8 |

.2 |

5.5 |

.1 |

||

|

HIP |

RA1 |

.1 |

0 |

.1 |

.1 |

0 |

.5 |

0 |

|

|

RA2 |

1.9 |

.1 |

.4 |

.3 |

.2 |

3 |

.1 |

||

|

PLA |

RA1 |

1.6 |

.2 |

4.5 |

1.4 |

.4 |

5.2 |

.1 |

|

|

RA2 |

3.9 |

.5 |

6.4 |

1.8 |

1.1 |

5.3 |

.1 |

||

|

INT |

RA1 |

.1 |

.1 |

0 |

.1 |

0 |

.5 |

0 |

|

|

RA2 |

1.1 |

.6 |

.2 |

.8 |

.3 |

3.6 |

.1 |

||

|

COM |

RA1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.1 |

.5 |

.1 |

|

|

RA2 |

.5 |

.1 |

.3 |

.4 |

0 |

2.4 |

.1 |

||

Observation: OBS /Research Question: PRI /Predictions: PDC /Hypotheses:

HIP /Planning and experimentation: PLA /Interpretation: INT /Communication: COM

/Feedback: FDB /Hints: PST /Instructions: INS /Explanations: EXP/ Models: MOD

/Questions: PRE /Others: OTR

Figure 2

T-patterns dendrograms between

science process skills and scaffolding means used by PTs at school in RA1 and

RA2

4. Discussion and conclusions

The deployment of scientific

inquiry is still incipient in elementary education classrooms, thus giving PTs

few opportunities for experimentation (García‐Carmona et al., 2017), in addition to their low mastery and knowledge of

science process skills (Nilsson & Loughran, 2012). In the present study,

the results show the effectiveness of the training process centred on the

analysis of video to compensate for these circumstances. Below, the two

research questions posed are answered.

Following introductory

theoretical training, PTs were able to identify, similarly to the experts, both

the different science process skills involved in an inquiry process and the

scaffolding means in the video analysis of a teaching practice reference model.

Concerning these results, the following are highlighted (Table 1): a) a high

level of agreement between the PTs and the experts, especially notable in the

identification of Planning and Experimentation, which is also the science

process skill most often used in RA1; b) a low representation of the Research

Question and Interpretation skills in RA1, in contrast with a high presence of

these skills in the video analysis and a greater incidence in RA2. These

findings allow us to claim that the training process centred on video analysis

has facilitated the theory to practice the transfer of science process skills

and scaffolding means to the primary school classroom (García-Fernández &

Benítez-Roca, 2000; Gaudin & Chaliès, 2015;

Richards et al., 2021). The use of online video observation tools has probably

contributed to the high convergence in identifications (Blikstad-Balas

& Sørvik, 2015; Jewitt, 2012). These tools allow sequences to be played, paused and replayed, which has led to a better understanding

and appropriation of the pedagogical knowledge linked to scientific inquiry

methodology (Klette & Blikstad-Balas, 2018).

The study of PTs' classroom interventions before the training (RA1)

allows us to identify them closer to scientific demonstration and introduce

content knowledge mainly from a theoretical approach (García‐Carmona et al., 2017; Solé-Llussà et al.,

2018). This is consistent with the T-patterns observed in RA1, where an almost

exclusive repetition of Observation

and Planning and Experimentation is

observed (Figure 2). In RA2, the transition from more conventional models

towards inquiry by integrating the different science process skills is

emphasised. More complex T-patterns are observed, with a significant increase

in the frequency and variety of science process skills (Table 2). The

T-patterns also show that PTs introduce similar inquiry sequences to those they

have observed during the video analysis task, by extrapolating the expert

teacher's actions to their own teaching practice. This suggests a modelling

function of the video as it encourages transferability to the school classroom

(Roth et al., 2019; Zaragoza et al., 2021).

Regarding the use of teaching scaffolds,

no changes are observed between RA1 and RA2, which indicates that they are

implemented in a similar degree of variety and amount. Nevertheless, in RA2 the

scaffolding means used are far more associated with the development of science

process skills to promote inquiry. In particular, Questions and Feedback stand out

as the means with the highest simultaneity with the set of science process

skills used (Table 3). This may be explained by their pertinence to general

rather than specific pedagogical content, as well as their effectiveness both

in promoting participation through communication and also

as means of monitoring pupils' comprehension (van de Pol et al., 2011). Planning and Experimentation is the most

frequent skill in the interventions perform by PTs at schools and the one that

involves the greatest diversity of scaffoldings (Table 2 and Table 3). On the

one hand, it is a skill that requires a major cognitive effort on the part of

school pupils. So, it is possible that this may lead to a more varied and

greater use of scaffolding means by PTs (Kruit et al., 2018; Rönnebeck et al., 2016). Moreover, this situation could be

taken as an example of the modelling function of the expert teacher's video,

which shows the relevance of planning and the need for planning to be supported

by different scaffolding means. Hence the importance of providing reference

models during initial training that reflects the integrity and complexity of

teacher performance.

The limitations of this study

include the reduced sample size and its non-probabilistic selection since it

focuses on a specific group of students in dual training. In addition, during

the COVID-19 pandemic, the temporary closure of schools hindered data

collection, reducing the number of participants and the generalisability of the

results. Yet, this research has exploratory and descriptive value as an

observational study in PTs’ scientific inquiry

training, considering the lack of contributions in this field. Therefore, an

iteration with a control group is needed to achieve a statistical comparison of

the design's formative impact. As proposed by Blomberg et al. (2013), future

studies should include a greater variety of videos in which the different

science process skills are sufficiently represented for their identification

and analysis throughout the interventions. It is also recommended to design and

validate instruments for video analysis, promoting higher agreement among the

observers.

In conclusion, the findings of

this study and the potential future lines of action could provide insights to

address the training needs in science pedagogy that have been reported in the

international literature and reports.

5. Acknowledgments

The authors would like to

thank the school principals, teachers, families and

pupils, as well as the preservice teachers, for their willingness to

participate and for their authorisation to collect data in their classrooms.

6. Funding

This research was carried out

within the Competences, Technology and Society in Education Research Group

(COMPETECS, 2021 SGR 01360). The authors are grateful for the support received

from 2020 ARMIF 00019 of the Agència d'Ajuts per a la Rercerca i Universitats (AGAUR) and the Departament d'Economia i Societat del Coneixement de Catalunya, as well as the support of the

University of Lleida through the Research Promotion Programme 2019. In

addition, this research article has received a grant for its linguistic

revision from the Language Institute of the University of Lleida (2023 call).

References

Alles, M., Seidel, T.,

& Gröschner, A. (2019). Establishing

a positive learning atmosphere and conversation culture in the context of a

video-based teacher learning community. Professional Development in Education, 45(2), 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1430049

Alpert, F. & Hodkinson, C.

S. (2019). Video use in lecture classes: Current practices, student perceptions

and preferences. Education and Training, 61(1), 31-45. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2017-0185

Anguera,

M. T., Blanco-Villaseñor, Á., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Losada, J. L. (2011).

Diseños observacionales: ajuste y aplicación en psicología del deporte. Cuadernos de Psicología Del Deporte, 11(2),

63–76. https://revistas.um.es/cpd/article/view/133241

Anguera,

M. T., Blanco-Villaseñor, A., Losada, J. L., & Sánchez-Algarra, P. (2020).

Integración de elementos cualitativos y cuantitativos en metodología

observacional. Ámbitos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación, 49,

49–70. https://doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2020.i49.04

Blikstad‐Balas, M., & Sørvik, G. O. (2015). Researching

literacy in context: using video analysis to explore school literacies. Literacy, 49(3), 140-148. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12037

Blomberg, G., Renkl, A., Gamoran Sherin, M., Borko, H., & Seidel, T.

(2013). Five research-based heuristics for using video in pre-service teacher

education. Journal for Educational

Research Online, 5(1), 90–114. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:8021

Cebrián-Robles, D. (2022). CoAnnotation. https://coannotation.com/

Chan, K. K. H., Xu, L.,

Cooper, R., Berry, A., & van Driel, J. H. (2020). Teacher noticing in

science education: do you see what I see? Studies

in Science Education, 57(1),

1-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2020.1755803

Cohen, J. (1960). A

coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

Coiduras, J. L., Blanch, A. & Barbero, I. (2020). Initial

teacher education in a dual-system: Addressing the

observation of teaching performance. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 64, 100834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.100834

Colomo-Magaña,

E., Gabarda-Méndez, V., Cívico-Ariza, A., & Cuevas-Monzonís,

N. (2020). Percepción de estudiantes sobre el uso del videoblog como recurso

digital en educación superior. Pixel-Bit. Revista de

Medios y Educación, 59, 7-25. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.74358

Criswell, B., Krall, R., &

Ringl, S. (2022). Video Analysis and Professional Noticing in the Wild of Real

Science Teacher Education Classes. Journal

of Science Teacher Education, 33(5),

531-554. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2021.1966161

Durmaz, H., & Mutlu, S. (2016).

The effect of an instructional intervention on elementary students’ science

process skills. The Journal of

Educational Research, 110(4), 433–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/

00220671.2015.1118003

Exploratorium (2021). Magnet investigation. https://www.exploratorium.edu/education/ifi/inquiry-and-eld/educators-guide/magnet-investigation

García-Carmona,

A., Criado, A. M., & Cruz-Guzmán, M. (2017). Primary pre-service teachers’ skills in planning a

guided scientific inquiry. Research in

Science Education, 47(5), 989–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9536-8

García-Fernández, M. D., & Benítez-Roca, M. V.

(2000). Reconceptualización de la profesión docente mediante el empleo del

vídeo. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 14,

77–82. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/pixel/article/view/61146

Gaudin, C., & Chaliès, S. (2015). Video viewing in teacher education and

professional development: A literature review. Educational Research Review, 16, 41–67. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.edurev.2015.06.001

Goodwin, C. (1994).

Professional vision. American

anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

Goodwin, C. (2015).

Professional Vision. In S. Reh, K. Berdelmann, &