Revisión sistemática de instrumentos

que evalúan la calidad de aplicaciones móviles de salud

Systematic review of instruments that assess the quality of

mobile health applications

Claudio

Delgado-Morales. Personal investigador en

formación. Universidad de Huelva, España

Claudio

Delgado-Morales. Personal investigador en

formación. Universidad de Huelva, España

Dra. Ana

Duarte-Hueros. Profesora Titular de Universidad.

Universidad de Huelva, España

Dra. Ana

Duarte-Hueros. Profesora Titular de Universidad.

Universidad de Huelva, España

Recibido:

2023/01/12 Revisado:2023/01/28 Aceptado: 2023/03/30 Preprint: 2023/04/13 Publicado:2023/05/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Delgado-Morales,

C., & Duarte-Hueros, A. (2023). Revisión sistemática de instrumentos que

evalúan la calidad de aplicaciones móviles de salud [Systematic review of

instruments that assess the quality of mobile health applications]. Pixel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, 67, 35-58. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.97867

RESUMEN

En los últimos años ha aumentado

significativamente la descarga de aplicaciones móviles (apps) orientadas a

desarrollar hábitos saludables en la población en general. No obstante, la

mayoría no están sujetas a procesos de regulación de calidad, y los

instrumentos de evaluación disponibles pueden estar obsoletos. Esta revisión se

ha realizado para conocer el estado del arte sobre procesos de diseño,

construcción, validación y principales resultados obtenidos en estudios

empíricos acerca de los instrumentos de evaluación de la calidad de dichas

apps, todo ello a fin de identificar las principales dimensiones e indicadores

comunes. Se han llevado a cabo búsquedas en cuatro bases de datos de alto

impacto. Se concluye que es un tema de interés reciente y actual en la

literatura científica. De 11 documentos incluidos, se han hallado 97

indicadores organizados en 17 dimensiones. Sólo en dos de ellos se incluyeron

aspectos relacionados con la privacidad y la seguridad. En definitiva, se ha

configurado una lista significativa y actualizada que podrá ser la base para

construir un marco de evaluación que permita hacer un estudio integral de estas

apps, pues muchos de los instrumentos de evaluación no han sido diseñados

pensando en la población en general.

ABSTRACT

The download of the mobile

applications (apps) aimed at fostering healthy habits in the general population

has increased significantly in recent years. However, the majority of these

apps are not subject to quality regulation processes, and the available instruments

to assess the quality seem to be obsolete. This review has been made to know

the state of the art about the processes of design, construction, validation

and main results obtained in empirical studies about the instruments for

assessing the quality of said apps, all this in order to identify the main

dimensions and common indicators. Searches have been conducted in four

databases with high impact. It concludes that is an interest current topic in

scientific literature. From 11 documents which have been included, 17

dimensions and 97 indicators have been considered. Privacy and security-related

issues were only included in two documents. In short, it has been possible to

establish a significant and updated list that may be the basis for constructing

an evaluation framework that allows a comprehensive study of these apps,

considering that many of the assessment instruments have not been designed for

the general population.

PALABRAS CLAVES· KEYWORDS

Instrumento; evaluación; calidad; aplicación móvil;

hábitos saludables

Instrument; evaluation; quality; mobile application;

healthy habits

1. Introducción

Cada vez es mayor el uso cotidiano de las apps, pues

se consideran herramientas tecnológicas con numerosas posibilidades para

agilizar y controlar casi cualquier aspecto de nuestra vida.

En la última década, y en concreto desde finales del

año 2019, a causa de la COVID-19, se han incrementado exponencialmente sobre

todo el desarrollo y la publicación de apps sobre salud. Como señalan

Collado-Borrell et al. (2020), el inicio de la pandemia y sus efectos han sido

todo un punto de inflexión en el panorama de la mHealth. Este término, en

español mSalud (salud móvil), fue adoptado por la Organización Mundial de la

Salud (OMS, 2011, p.6) y engloba la “práctica médica y de salud pública

respaldada por dispositivos móviles, como teléfonos móviles, dispositivos de

monitoreo, asistentes digitales personales (PDA) y otros dispositivos

inalámbricos”.

Según Aitken and Nass (2021), actualmente existen más

de 350,000 apps relacionadas con la salud disponibles en todo el mundo. Y este

número no para de aumentar. Sin embargo, la gran mayoría no se basan en

evidencia científica ni han sido sometidas a procesos de regulación de calidad

y fiabilidad (Boudreaux et al., 2014; Duarte-Hueros et al., 2021;

Jake-Schoffman et al., 2017; Palacios et al., 2020). Como en su momento

reflexionaban Powell et al. (2014) en relación con la salud en general, el

creciente aumento del número de apps disponibles dificulta las tareas de

revisión y certificación que sería necesario llevar a cabo. Esto ha dado lugar

a una amplia desinformación entre la población y a la adopción de conductas

negativas para la salud al usar apps de baja calidad (BinDhim et al., 2015).

Si bien es cierto, como apuntan Lee and Cherner

(2015), que resulta prácticamente imposible crear un instrumento universal que

permita evaluar todas y cada una de las apps existentes debido a la diversidad

de temáticas y propósitos, así como a las continuas actualizaciones, también lo

es que muchas de las herramientas de evaluación disponibles (escalas, rúbricas,

listas de verificación, etc.) carecen de un enfoque multidimensional;

observándose demasiada heterogeneidad en los criterios de evaluación (Nouri et

al., 2018). En numerosas ocasiones, estos criterios son difíciles de

comprender, muy genéricos a veces e, incluso, demasiado específicos con

respecto a un aspecto de la salud en concreto (Stoyanov et al., 2015); o

simplemente, han quedado obsoletos para ayudar a la población en general a

seleccionar adecuadamente este tipo de tecnología. Todo ello hace que, como

recalcan Azad-Khaneghah et al. (2021), hoy en día sea tan complejo localizar un

instrumento de evaluación correcto como localizar una app idónea.

Con base en los argumentos anteriores, se ha llevado a

cabo una revisión de la literatura para conocer el estado del arte en relación

con los procesos de diseño, construcción, validación y principales resultados

recogidos en estudios empíricos sobre instrumentos de evaluación de la calidad

de apps orientadas a desarrollar hábitos saludables en la población en general.

El objetivo final de esta revisión ha sido identificar los instrumentos

utilizados en estudios previos, así como determinar las principales dimensiones

e indicadores comunes utilizados en los mismos.

2. Metodología

De acuerdo con el estudio de Grant and Booth (2009),

en el que se reconocen y describen hasta 14 tipos diferentes de revisiones de

literatura, la metodología seguida en esta investigación se ha desarrollado

siguiendo las pautas propias de la revisión sistemática, con un análisis de los

resultados de tipo bibliométrico seguido de un análisis cualitativo de los

estudios finalmente seleccionados.

El método utilizado ha seguido las directrices de la

Declaración PRISMA. De acuerdo con ella, durante el mes de marzo de 2022 se ha

llevado a cabo una consulta sistemática de las bases de datos bibliográficas de

relevancia en la investigación educativa: Web of Science y Scopus, y en las

bases de datos PubMed y Cochrane Library, por su especialización en Ciencias de

la Salud.

Los tópicos combinados en los que se ha centrado la

búsqueda han sido los siguientes: ((development OR validation) AND (instrument

OR tool OR method) AND (evaluation OR assessment) AND quality AND (“mobile

application” OR app) AND health*).

Como criterios de inclusión, se han tenido en cuenta:

(1) áreas temáticas de Ciencias Sociales, Ciencias de la Salud y Tecnología,

(2) apps relacionadas con la mHealth y (3) apps dirigidas a la población en

general.

No se han acotado las búsquedas con respecto al año de

publicación, tipo de documento, número de citas ni idioma para evitar excluir

posibles estudios afines.

De este modo, una vez cruzados los datos y eliminadas

las duplicidades del total de registros, se ha procedido a analizar el título,

el resumen y las palabras clave para confirmar aquellos que tenían que ver con

nuestro tema objeto de estudio, seleccionando los que describían el proceso de

investigación completo.

Como sistema de evaluación crítica de inclusión con

vistas a la selección final de documentos según la calidad metodológica, se ha

usado la herramienta MMAT de evaluación de métodos mixtos para revisiones

sistemáticas (Pluye et al., 2011) ya que se puede aplicar en investigaciones

basadas en cualquier tipo de diseño, dando lugar a una revisión integradora

completa (Coyne et al., 2018).

Las métricas de puntuación proporcionadas por MMAT

son: no clasificado (valor 0; falta de calidad), 25% de calidad, 50% de

calidad, 75% de calidad y 100%, es decir, mayor calidad metodológica del

estudio.

Después de la fase de extracción y evaluación con

MMAT, los datos han sido resumidos y sintetizados.

A continuación, se han extraído las dimensiones y los

indicadores de los estudios incluidos para identificar lo común a todos ellos.

Esta primera lista se ha refinado para eliminar las duplicidades.

Por último, a través de un nuevo análisis y depuración

de los ítems, se ha llevado a cabo una reorganización de las dimensiones y los

indicadores resultantes para confirmar que cada indicador estaba asociado a la

dimensión adecuada y esta, a su vez, quedaba claramente diferenciada del resto

por una descripción/explicación de lo que contenía.

3. Análisis y resultados

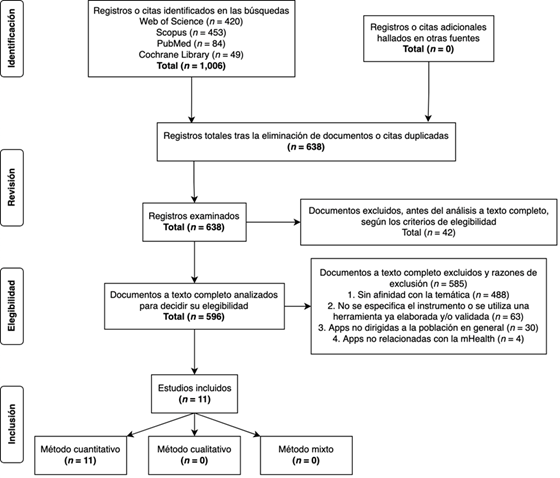

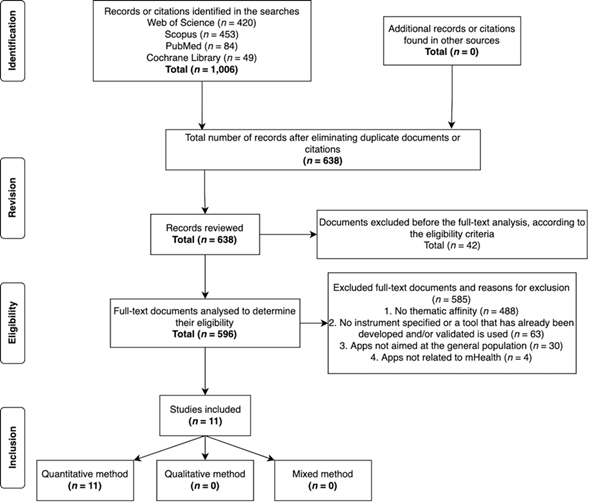

Se han identificado un total de 1,006 documentos. Tras

cruzar los datos y eliminar 368 duplicidades, se ha examinado el título, el

resumen y las palabras clave del resto (638 documentos). De estos, 42 han sido

excluidos al no cumplir con los criterios de elegibilidad fijados (indicados en

la Figura 1).

Los 596 documentos restantes han sido analizados a

texto completo para determinar su elegibilidad, lo que ha llevado a la

exclusión de 585 por las siguientes razones: (1) sin afinidad con la temática =

488; (2) no se especifica el instrumento o se utiliza una herramienta ya

elaborada y/o validada = 63; (3) apps no dirigidas a la población en general =

30; y (4) apps no relacionadas con la mHealth = 4. Este análisis ha sido

llevado a cabo de forma independiente por el autor C.D. y la autora A.D.,

resolviéndose cualquier discrepancia surgida mediante discusión y consenso.

Así pues, un total de 11 artículos se han incluido

finalmente para realizar el análisis documental detallado (Figura 1).

The mention of platforms as a novel advancement in

higher education may seem outdated due to the pandemic's reliance on

technology. Nowadays, it is challenging for educational institutions to

function without one.

The

use of digital technologies in higher education to promote the commodification

of education processes and practices has significant consequences. The

platformization of higher education is not a neutral shift, as platforms impact

institutions' values, culture, strategy, operations and outcome assessment.

These concerns about unrestricted platform use range from privacy issues to

changes in working conditions or profiles for teachers (Castañeda & Selwyn,

2018; Webber & Zheng, 2020). However, the potential impact on teaching and

learning cannot be ignored.

This

article explores the widespread use of platforms in universities, covering

their integration into various aspects such as administration and teaching. It

then examines stakeholder expectations for these platforms to transform higher

education while highlighting significant problems they present at institutional

and system levels. The dangers of platformization are summarized before

potential solutions are discussed to address these difficulties aligned with

the goals of higher education. Finally, lessons learned from this study are

presented as implications for future research and practice.

Diagrama de flujo PRISMA

Fuente:

Basado en Moher et al. (2009)

En relación

con la calidad metodológica, los 11 artículos evaluados con MMAT han sido

incluidos ya que no ha habido ninguno con una calidad débil de sus componentes,

lo que ha dado lugar a una síntesis de estudios con una calidad alta-muy alta a

partir de la evidencia hallada (todos los estudios han cumplido con al menos el

75% de los criterios establecidos en la herramienta). De nuevo, el autor C.D. y

la autora A.D., de forma independiente, han sometido la lista final de los

artículos susceptibles de ser incluidos a esta evaluación de la calidad, y se

ha discutido cualquier desacuerdo para llegar a un consenso en la selección de

los mismos.

Los

resultados que se han obtenido de la evaluación crítica con MMAT para cada uno

de los documentos finalmente seleccionados se insertan en la siguiente tabla

(Tabla 1).

Tabla 1

Evaluación crítica de la calidad mediante MMAT (Pluye et al., 2011)

|

|

2. Cuantitativo controlado aleatorio |

4. Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Puntuación general de la calidad |

||||||||

|

Referencias |

2.1 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

|

||

|

Bardus

et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Baumel

et al. (2017) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Böhme

et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

|

No |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

*** |

||

|

Domnich

et al. (2016) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Llorens-Vernet

and Miró (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

No |

Sí |

Sí |

*** |

||

|

Martín-Payo

et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Messner

et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Saliasi

et al. (2021) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Stoyanov

et al. (2015) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

Stoyanov

et al. (2016) |

Sí |

No |

Sí |

Sí |

|

|

|

|

*** |

||

|

Terhorst

et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

Sí |

**** |

||

|

*cumple con el 25% de los

criterios **cumple con el 50% de los

criterios ***cumple con el 75% de los

criterios ****cumple con el 100% de

los criterios n.c. (no clasificado) |

|||||||||||

Notas: Basado en Willis et al. (2019)

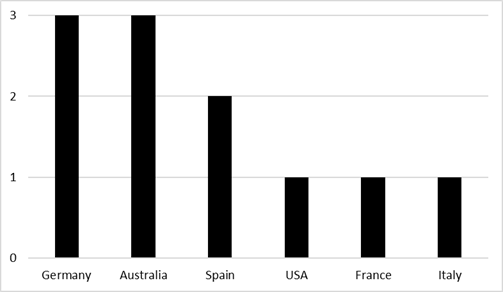

Los estudios

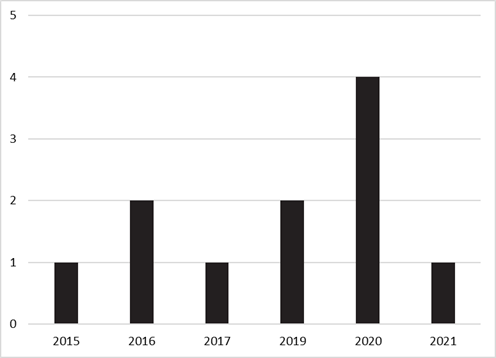

que se han incluido se sitúan geográficamente en seis países diferentes (Figura

2), publicándose la mayoría de ellos entre 2019 y 2021, y ampliándose el

periodo de publicación desde el año 2015 con el primer artículo elegible para

la revisión (Figura 3).

Países de origen de los

estudios incluidos

Figura 3

Año de publicación de los

estudios incluidos

En todos

los artículos se emplearon metodologías cuantitativas. En este sentido,

teniendo en cuenta los subdominios metodológicos, se han identificado diez con

un diseño cuantitativo descriptivo (Bardus et al., 2020; Baumel et al., 2017;

Böhme et al., 2019; Domnich et al., 2016; Llorens-Vernet &

Miró, 2020; Martín-Payo et al., 2019; Messner et al., 2020; Saliasi

et al., 2021; Stoyanov et al., 2015; Terhorst et al., 2020) y tan solo uno con

un diseño cuantitativo controlado aleatorio (Stoyanov et al., 2016).

Referente

a la evaluación con MMAT, de los estudios que utilizaron una metodología

centrada en un diseño cuantitativo descriptivo, se ha percibido en un artículo

una falta de justificación en la relevancia del tamaño de la muestra (Böhme

et al., 2019). No obstante, Böhme et al. (2019) reconocieron que el haber

utilizado exclusivamente apps alemanas

supuso una limitación en el estudio.

Por

otro lado, de nuevo dentro de este subdominio, ha habido un artículo que no ha

informado acerca de las razones por las que ciertos sujetos elegibles

decidieron no participar tanto en la primera como en la segunda ronda del

método Delphi (Llorens-Vernet & Miró, 2020). Aun así, comentaron que

las diferencias entre las rondas fueron mínimas a pesar de que no todos los

sujetos de la primera ronda (n = 42) participaron en la siguiente (n = 24), por

lo que el número de sujetos participantes en cada ronda fue apropiado para los

objetivos propuestos.

El

único artículo de corte cuantitativo controlado aleatorio no ha proporcionado

suficientes detalles sobre el ocultamiento de la asignación o el cegamiento

posterior a la aleatorización (Stoyanov et al., 2016). Según Schulz and Grimes

(2002), el ocultamiento de la asignación es un método utilizado en los ensayos

controlados aleatorios para evitar el sesgo de selección, así como para

proteger una secuencia de asignación antes y hasta el propio momento de la

asignación. En cambio, con el cegamiento se mantienen a los sujetos

participantes y/o a las personas responsables del estudio ajenas a la

intervención asignada para evitar cualquier posible influencia, protegiéndose

de esta manera la secuencia después de la asignación.

Atendiendo

al objetivo de los estudios, el desarrollo de un instrumento, una herramienta o

un método de evaluación únicamente se ha abordado en dos artículos, en los

cuales se ha incluido el proceso de validación. Baumel et al. (2017)

presentaron la herramienta Enlight,

que es un conjunto de escalas para evaluar la calidad de los programas

pertenecientes a la salud electrónica o cibersalud. Por su parte, Stoyanov et

al. (2015) dieron a conocer la multidimensional Mobile App Rating Scale

(MARS) para determinar la calidad de las apps

de salud.

En

cuanto al mecanismo de medición utilizado en dichas escalas, en ambos estudios

se ha construido una escala tipo Likert de cinco puntos.

Lo

más frecuente ha sido la traducción, adaptación y validación a otro idioma de

un instrumento, una herramienta o un método de evaluación previamente

desarrollado, en concreto la escala MARS diseñada por Stoyanov et al. (2015).

Así ha sido en cinco de los artículos consultados: Bardus et al. (2020),

Domnich et al. (2016), Martín-Payo et al. (2019), Messner et al. (2020) y

Saliasi et al. (2021). Asimismo, el desarrollo y/o la validación de una versión

alternativa se ha llevado a cabo en dos artículos (Böhme et al., 2019; Stoyanov

et al., 2016).

Los

artículos restantes se han centrado en el proceso de validación de un

instrumento, una herramienta o un método de evaluación construido con

anterioridad. Por un lado, Llorens-Vernet and Miró (2020) validaron la Mobile App Development and Assessment Guide (MAG), una guía inédita

basada en una checklist o lista de

verificación para ayudar a diseñar, desarrollar y analizar, en términos de

calidad, las apps propias de la mHealth. Y, por otro lado, Terhorst et

al. (2020) se ocuparon de la evaluación psicométrica de la escala incluida en

el citado estudio de Stoyanov et al. (2015).

La

relación de artículos finalmente incluidos puede consultarse en la Tabla 2, en

la que se ofrece información detallada en relación con la autoría, año de

publicación, diseño, objetivos, principales resultados y puntajes MMAT.

Tabla 2

Resumen de los estudios incluidos

|

Autoría |

Año |

Diseño |

Objetivo(s) |

Principales resultados |

Punt. MMAT |

|

Stoyanov et al. |

2015 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Desarrollar una escala de

evaluación (MARS) |

Escala MARS. Excelente

consistencia interna: α = .90 (también altos valores en todas las

dimensiones). Excelente fiabilidad entre evaluadores: CCI = .79 |

100%

(****) |

|

Domnich et al. |

2016 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Traducir, adaptar y validar

al italiano la escala MARS |

Escala MARS-It. Excelente

consistencia interna: α = .90 y .91 (ambos evaluadores). Excelente

fiabilidad entre evaluadores: CCI = .96 |

100%

(****) |

|

Stoyanov et al. |

2016 |

Cuantitativo controlado

aleatorio |

Desarrollar y validar la

versión de usuario de la escala MARS (uMARS) |

Escala uMARS. Excelente

consistencia interna: α = .90 (también altos valores en todas las

dimensiones). La puntuación total y las dimensiones tuvieron unos buenos

niveles de fiabilidad entre evaluadores test-retest durante los periodos de

uno a dos meses y tres meses: CCI = .66 y .70 |

75%(a)

(***) |

|

Baumel et al. |

2017 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Desarrollar y validar una

herramienta de evaluación (Enlight) |

Herramienta Enlight. Excelente consistencia

interna: α = rango .83-.90 (también altos valores en todas las

dimensiones). Excelente fiabilidad entre evaluadores: CCI = rango .77-.98 |

100%

(****) |

|

Böhme et al. |

2019 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Desarrollar una herramienta

de evaluación basada en la escala MARS |

Herramienta basada en la

escala MARS. Validación/Evaluación psicométrica n.p. |

75%(b)

(**) |

|

Martín-Payo et al. |

2019 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Traducir, adaptar y validar

al español la escala MARS |

Escala MARS-Sp. Alta

consistencia interna: α = >.77 (independientemente del evaluador).

Alta fiabilidad entre evaluadores: CCI = >.76. También altos valores en la

correlación de las dimensiones |

100%

(****) |

|

Bardus et al. |

2020 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Traducir, adaptar y validar

al árabe la escala MARS |

Escala MARS-Ar. Buena consistencia

interna: α = .96 (compromiso), .94 (estética), .81 (calidad de la

información) y .71 (funcionalidad). Buena fiabilidad entre evaluadores: CCI =

.83. Escala altamente alineada con la versión original |

100%

(****) |

|

Llorens-Vernet and Miró |

2020 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Validar la guía MAG |

Se establecieron un total

de 48 criterios finales (método Delphi). Usabilidad, privacidad y seguridad

fueron las dimensiones que incluyeron los criterios más relevantes |

75%(c)

(***) |

|

Messner et al. |

2020 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Traducir, adaptar y validar

al alemán la escala MARS |

Escala MARS-G. Buena

consistencia interna: Omega = rango .72-.91. Alta fiabilidad entre evaluadores:

CCI = .83. También altos valores en la correlación de las dimensiones. Escala

excelentemente alineada con la versión original |

100%

(****) |

|

Terhorst et al. |

2020 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Validar la escala MARS |

El AFC generó un modelo

bifactorial con un factor general y un factor para cada dimensión.

Buena/excelente consistencia interna: Omega = rango .79-.93. Alta fiabilidad

entre evaluadores: CCI = .82. También altos valores en la correlación de MARS

con la herramienta Enlight |

100%

(****) |

|

Saliasi et al. |

2021 |

Cuantitativo descriptivo |

Traducir, adaptar y validar

al francés la escala MARS |

Escala MARS-F. Aceptable

consistencia interna: Omega = .79 (compromiso), .79 (funcionalidad), .78

(estética) y .61 (calidad de la información). También altos valores en la

correlación de las dimensiones. Escala bien alineada con la versión original |

100%

(****) |

|

Notas: (a) No se especifica el método de ocultamiento de la asignación

o el cegamiento posterior a la aleatorización. (b) Se percibe falta de justificación en la relevancia

del tamaño de la muestra (prueba piloto). (c) No se explican las razones por las que ciertos sujetos

elegibles decidieron no participar en las rondas del método Delphi. |

|||||

|

AFC –

Análisis factorial confirmatorio. |

|||||

CCI – Coeficiente de correlación intraclase.

MAG – Mobile App Development and Assessment Guide (guía de evaluación y desarrollo de apps).

MARS – Mobile App Rating Scale (escala de calificación de apps).

MMAT – Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (herramienta de evaluación de métodos

mixtos).

n.p. – No proporcionado.

A continuación,

se han extraído todas las dimensiones e indicadores utilizados en dichos

artículos, resultando en 59 dimensiones y 282 indicadores en total. Tras

eliminar duplicidades y fusionar dimensiones e indicadores similares, la lista

final ha quedado conformada por un total de 97 indicadores agrupados en 17

dimensiones (tabla 3). Para delimitar de forma clara la especificidad de cada

dimensión, se ha realizado una explicación/descripción detallada de lo que

contenían. Esta información no se ha incluido en este documento por motivos de

espacio, pero puede solicitarse a las personas responsables del estudio.

Tabla 3

Relación de dimensiones consideradas

|

Dimensiones |

|

|

1.

Compromiso/Participación |

10. Soporte

técnico y actualizaciones |

|

2.

Funcionalidad (técnica/tecnología) |

11.

Psicoterapia |

|

3.

Funcionalidad (usabilidad) |

12.

Psicoterapia (usabilidad) |

|

4.

Funcionalidad (accesibilidad) |

13.

Seguridad de uso |

|

5.

Estética/Diseño visual |

14. Calidad/Evaluación

subjetiva |

|

6.

Información |

15.

Calidad/Evaluación subjetiva (predisposición) |

|

7.

Información (base científica) |

16.

Persuasión terapéutica |

|

8.

Información (ética) |

17.

Alianza terapéutica |

|

9. Privacidad/Seguridad

de datos |

|

4. Discusión

En

primer lugar, con respecto al análisis bibliométrico realizado, se ha observado

que la fecha de publicación de documentos relacionados con la temática objeto

de estudio se inicia en 2015; hecho que demuestra que la evaluación de apps del ámbito de la mHealth es

un tema de interés reciente en lo que a la literatura científica se refiere, coincidiendo

con los resultados obtenidos en otros estudios (Azad-Khaneghah et al., 2021;

Nouri et al., 2018). Alemania y Australia son los países que concentran la

mayor parte de las investigaciones sobre el tema.

En

consonancia con estudios como el de Azad-Khaneghah et al. (2021), resulta

llamativo el gran número de trabajos hallados que se refieren a la escala MARS

al ser la primera herramienta para medir la calidad de las apps de salud. Si bien se ha adaptado a diferentes idiomas y

versiones, y ha adquirido un evidente reconocimiento en la comunidad científica

(Bardus et al., 2020; Böhme et al., 2019; Domnich et al., 2016;

Martín-Payo et al., 2019; Messner et al., 2020; Saliasi et al., 2021;

Stoyanov et al., 2016), se evidencian algunas carencias, pues no se incluyen

dimensiones ni indicadores relacionados con temas de privacidad y seguridad;

resultados a los que también llegaron Hensher et al. (2021) y Jeminiwa et al.

(2019).

Según

los resultados del estudio sistemático realizado por Duarte-Hueros et al.

(2021) sobre las iniciativas españolas acreditadoras de calidad y sus procesos

de regulación en apps del campo de la

salud, se ha observado que los indicadores, los criterios y las recomendaciones

contenidas en tales iniciativas tienen similitudes relevantes con esta

revisión. Buena parte de las recomendaciones del distintivo AppSaludable

y de los criterios del servicio de certificación Acreditació FTSS aparecen entre los resultados que aquí se han

presentado. Aunque existen algunas coincidencias, la terminología empleada es,

en líneas generales, distinta.

Además,

algo significativo en estas iniciativas es que se valoran variables relacionadas

con la privacidad y la seguridad; dos dimensiones que, en este caso y a

diferencia de la mayoría de los instrumentos de evaluación analizados, sí han

sido consideradas y convenientemente descritas en el presente estudio.

5. Conclusiones

De

acuerdo con los datos obtenidos a partir de la herramienta MMAT en relación con

el diseño metodológico seguido en los estudios analizados, se concluye que la

investigación en esta área se ha abordado en su mayor parte desde una

perspectiva cuantitativa descriptiva, mostrando una calidad metodológica

notable: los 11 artículos han cumplido con al menos el 75% de los criterios

contemplados en la herramienta.

A

partir de las distintas dimensiones e indicadores comunes identificados en los

estudios analizados, y de la información contrastada con otros documentos, esta

investigación supone el punto de partida para la construcción de un marco de

evaluación de la calidad de apps;

máxime considerando que las escalas/instrumentos disponibles en la actualidad

no se orientan a la evaluación de apps para

la población en general (Azad-Khaneghah et al., 2021) ni a apps que fomenten/desarrollen hábitos saludables.

En ninguno de los estudios se incluyen

descripciones/explicaciones claras de cada dimensión. Al respecto, esta investigación

es novedosa, ya que se ha hecho un esfuerzo para hacerlas más comprensibles y

mejorar su concordancia con el conjunto de indicadores asociados a cada una de

ellas.

En

cuanto a las limitaciones del estudio, hay que tener presente la naturaleza cambiante

y dinámica de la tecnología, por lo que se recomienda revisar con cierta

frecuencia las dimensiones y los indicadores hallados. En este sentido, a pesar

de haber consultado bases de datos de alto impacto científico (Web of

Science, Scopus, PubMed y Cochrane Library), se han

obviado indexaciones en otras bases de datos donde podría ubicarse literatura

valiosa sobre el tema objeto de estudio.

Con

perspectivas de futuro, se sugiere el desarrollo de estudios con diseños metodológicos controlados que, a su

vez, proporcionen una explicación en profundidad de cada dimensión e

indicadores, además de incluir categorías relacionadas con la privacidad y la

seguridad como parte de una evaluación integral de cualquier app.

6. Financiación

Este

trabajo ha sido apoyado por la Estrategia de Política de Investigación y

Transferencia de la Universidad de Huelva (ayudas predoctorales de Personal

Investigador en Formación, 2020).

Systematic review of instruments that assess the

quality of mobile health applications

1. Introduction

The daily use of apps is increasing, as they are seen

as technological tools with numerous possibilities to streamline and control

almost any aspect of our lives.

In the last decade, and specifically since the end of

2019 due to COVID-19, the development and release of health apps in particular

has increased exponentially. As Collado-Borrel et al. (2020) point out, the

onset of the pandemic and its effects have been a turning point in the mHealth

landscape. This term, mHealth (mobile health), was adopted by the World Health

Organisation (WHO, 2011, p.6) and encompasses "medical and public health

practice supported by mobile devices, such as mobile phones, monitoring devices,

personal digital assistants (PDAs) and other wireless devices".

According to Aitken and Nass (2021), there are

currently more than 350,000 health-related apps available worldwide. And this

number keeps growing. However, the vast majority are not based on scientific

evidence, nor have they been subject to quality and reliability regulation

processes (Boudreaux et al., 2014; Duarte-Hueros et al., 2021; Jake-Schoffman

et al., 2017; Palacios et al., 2020). As reflected by Powell et al. (2014) in

relation to health in general, the increasing number of apps available makes it

more difficult to carry out the necessary review and certification procedures.

This has led to widespread misinformation among the population and the adoption

of behaviours that have a negative effective on health due to using low-quality

apps (BinDhim et al., 2015).

While it is true, as Lee and Cherner (2015) point out,

that it is practically impossible to create a universal instrument to evaluate

each and every app that exists due to the diversity of topics and purposes that

they cover, as well as the continuous updates, it is also true that many of the

available evaluation tools (scales, rubrics, checklists, etc.) lack a

multidimensional approach; too much heterogeneity is found in the evaluation

criteria (Nouri et al., 2018). These criteria are often difficult to

understand, are sometimes too generic or are even too specific to a particular

aspect of health (Stoyanov et al., 2015), or they have simply become obsolete

in helping the general population to select this type of technology

appropriately. All of this means that, as Azad-Khaneghah et al. (2021)

emphasise, nowadays it is as difficult to find the right assessment tool as it

is to find a suitable app.

Based on the above arguments, a literature review has

been carried out to determine the state of the art in relation to the processes

of design, construction and validation, as well as the main results collected

in empirical studies carried out on the instruments used to assess the quality

of apps which are aimed at developing healthy habits in the general population.

The overall aim of this review has been to identify the instruments used in

previous studies, as well as to determine the main common dimensions and

indicators used in these studies.

2. Methodology

In accordance with the study by Grant and Booth

(2009), which recognises and describes up to 14 different types of literature

reviews, the methodology followed in this research has been developed following

the guidelines of the systematic review, with a bibliometric analysis of the

results followed by a qualitative analysis of the studies finally selected.

The method used has followed the guidelines of the

PRISMA Statement. Accordingly, during the month of March 2022, a systematic

consultation of important bibliographic databases in educational research was

carried out: Web of Science and Scopus, and in the PubMed and Cochrane Library

databases, for their specialisation in Health Sciences.

The topics on which the search focused were as

follows: ((development OR validation) AND (instrument OR tool OR method) AND

(evaluation OR assessment) AND quality AND (“mobile application” OR app) AND

health*).

For the inclusion criteria, the following were

considered: (1) thematic areas of Social Sciences, Health Sciences and

Technology, (2) apps related to mHealth and (3) apps aimed at the general

public.

Searches have not been narrowed down with respect to

year of publication, type of paper, number of citations or language to avoid

excluding possible related studies.

Thus, after cross-checking the data and eliminating

duplicates from the total number of records, we proceeded to analyse the title,

abstract and keywords to confirm those that were related to our topic of study,

selecting those that described the entire research process.

As a critical inclusion assessment system for the

final selection of papers according to methodological quality, the MMAT (mixed

methods appraisal tool) for systematic reviews (Pluye et al., 2011) has been

used, as it can be applied to research based on any type of design, resulting

in a comprehensive review (Coyne et al., 2018).

The scoring metrics provided by MMAT are: not

classified (value 0; lack of quality), 25% quality, 50% quality, 75% quality

and 100%, i.e., the highest methodological quality of the study.

After the extraction and evaluation phase with MMAT,

the data were summarised and synthesised.

The dimensions and indicators of the included studies

have been extracted below to identify commonalities. This initial list has been

refined to eliminate duplication.

Finally, through a re-analysis and refinement of the

items, a reorganisation of the dimensions and the resulting indicators was

carried out to confirm that each indicator was associated with the appropriate

dimension and that this, in turn, was clearly differentiated from the rest by a

description/explanation of what it contained.´

3. Analysis and

results

A total of 1006 documents were identified. After

cross-checking the data and eliminating 368 duplicates, the title, abstract and

keywords of the remaining 638 documents were examined. Of these, 42 were

excluded as they did not meet the eligibility criteria (shown in figure 1).

The remaining 596 documents were analysed in full to

determine their eligibility, leading to the exclusion of 585 for the following

reasons: (1) no thematic affinity = 488; (2) no instrument specified or a tool

that has already been developed and/or validated is used = 63; (3) apps not

aimed at the general population = 30; and (4) apps not related to mHealth = 4.

This analysis was carried out independently by author C.D. and author A.D.,

with any discrepancies resolved through discussion and consensus.

Thus, a total of 11 articles were finally included for

the detailed documentary analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram

Source: Based on

Moher et al. (2009)

In relation to methodological quality, all 11 articles

assessed with MMAT have been included as there were none with poor-quality components,

resulting in a synthesis of studies with a high/very high quality based on the

evidence found (all studies met at least 75% of the criteria set out in the

tool). Again, author C.D. and author A.D. independently submitted the final

list of articles for inclusion in this quality assessment, and any

disagreements were discussed in order to reach a consensus on the selection of

articles.

The results obtained from the critical assessment with

MMAT for each of the documents finally selected are inserted in Table 1 below.

Table 1

Critical quality assessment using MMAT (Pluye et al.,

2011)

|

|

2.

Quantitative randomised controlled |

4.

Descriptive quantitative |

General

quality score |

||||||||

|

References |

2.1 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

|

||

|

Bardus

et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Baumel

et al. (2017) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Böhme

et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

|

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

*** |

||

|

Domnich

et al. (2016) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Llorens-Vernet

and Miró (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

*** |

||

|

Martín-Payo

et al. (2019) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Messner

et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Saliasi

et al. (2021) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Stoyanov

et al. (2015) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

Stoyanov

et al. (2016) |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

*** |

||

|

Terhorst

et al. (2020) |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

**** |

||

|

*meets 25% of the criteria ** meets 50% of the criteria *** meets 75% of the criteria **** meets 100% of the criteria n.c. (not classified) |

|

||||||||||

Notes: Based on Willis

et al. (2019)

The studies included are geographically located in six

different countries (Figure 2), with most of them published between 2019 and 2021,

and with the publication period starting from 2015 with the first article

eligible for review (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Country of origin of the studies included

Figure 3

Year of publication of the studies included

Quantitative methodologies were used in all of the

articles. In this sense, taking into account the methodological subdomains, ten

have been identified with a descriptive quantitative design (Bardus et al.,

2020; Baumel et al., 2017; Böhme et al., 2019; Domnich et al, 2016;

Llorens-Vernet & Miró, 2020; Martín-Payo et al., 2019; Messner et al.,

2020; Saliasi et al., 2021; Stoyanov et al., 2015; Terhorst et al., 2020) and

only one with a quantitative randomised controlled design (Stoyanov et al.,

2016).

Regarding the assessment with MMAT, of the studies that

used a methodology focusing on a descriptive quantitative design, a lack of

justification of the relevance of the sample size has been perceived in one

article (Böhme et al., 2019). However, Böhme et al. (2019) acknowledged that

using only German apps was a limitation of the study.

Furthermore, again within this subdomain, one article

didn’t report on the reasons why certain eligible subjects decided to not

participate in both the first and second rounds of the Delphi method

(Llorens-Vernet & Miró, 2020). However, they reported that the differences

between rounds were minimal and despite the fact that not all subjects from the

first round (n = 42) participated in the following round (n = 24), the number

of subjects participating in each round was appropriate for the proposed

objectives.

The only quantitative randomised controlled article

has not provided sufficient detail on allocation concealment or

post-randomisation blinding (Stoyanov et al., 2016). According to Schulz and

Grimes (2002), allocation concealment is a method used in randomised controlled

trials to avoid selection bias, as well as to protect an allocation sequence

before and up to the point of allocation. Blinding, on the other hand, keeps

the participating subjects and/or the persons responsible for the study away

from the assigned intervention to avoid any possible influence, thus protecting

the post-assignment sequence.

In view of the objective of the studies, the

development of an assessment instrument, tool or method has only been addressed

in two articles, in which the validation process has been included. Baumel et

al. (2017) presented the Enlight

tool, which is a set of scales for assessing the quality of e-health

programmes. Meanwhile, Stoyanov et al. (2015) unveiled the multidimensional

Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS) to determine the quality of health apps.

As for the measurement mechanism used in these scales,

a five-point Likert-type scale was applied in both studies.

In most cases, a previously developed instrument, tool

or assessment method was translated, adapted and validated in another language,

specifically the MARS scale designed by Stoyanov et al. (2015). This was the

case in five of the articles consulted: Bardus et al. (2020), Domnich et al. (2016),

Martín-Payo et al. (2019), Messner et al. (2020) and Saliasi

et al. (2021). Furthermore, the development and/or validation of an alternative

version was carried out in two articles (Böhme et al., 2019; Stoyanov et al.,

2016).

The remaining articles focused on the validation process

of a previously constructed assessment instrument, tool or method. On the one

hand, Llorens-Vernet and Miró (2020) validated the Mobile App Development and

Assessment Guide (MAG), an unpublished guide based on a checklist to help

design, develop and analyse mHealth apps in terms of quality. On the other

hand, Terhorst et al. (2020) focused on the psychometric evaluation of the

scale included in the aforementioned study by Stoyanov et al. (2015).

The list of articles finally included can be found in

Table 2 below, which provides detailed information regarding authorship, year

of publication, design, objectives, main results and MMAT scores.

Table 2

Summary of the studies included

|

Authorship |

Year |

Design |

Objective(s) |

Main results |

MMAT score |

|

Stoyanov et al. |

2015 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Development of an

assessment scale (MARS) |

MARS scale. Excellent

internal consistency: α = .90 (also high values in all dimensions). Excellent

inter-rater reliability: ICC = .79 |

100% (****) |

|

Domnich et al. |

2016 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Translating, adapting and

validating the MARS scale in Italian |

MARS-It scale. Excellent

internal consistency: α = .90 and .91 (both raters). Excellent inter-rater

reliability: ICC = .96 |

100% (****) |

|

Stoyanov et al. |

2016 |

Quantitative randomised

controlled |

Developing and validating

the user version of the MARS scale (uMARS) |

uMARS scale. Excellent

internal consistency: α = .90 (also high values in all dimensions). The

total score and the dimensions had good levels of inter-rater test-retest

reliability during the one- to two-month and three-month periods: ICC = .66

and .70 |

75%(a) (***) |

|

Baumel et al. |

2017 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Developing and validating

an assessment tool (Enlight) |

Enlight Tool. Excellent internal

consistency: α = range .83-.90 (also high values in all dimensions).

Excellent inter-rater reliability: ICC = range .77-.98 |

100% (****) |

|

Böhme et al. |

2019 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Developing an assessment

tool based on the MARS scale |

Instrument based on the

MARS scale. Psychometric evaluation/validation n.p. |

75%(b) (**) |

|

Martín-Payo et al. |

2019 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Translating, adapting and

validating the MARS scale in Spanish |

MARS-Sp scale. High

internal consistency: α = >.77 (independent of rater). High

inter-rater reliability: ICC = >.76. High values in the correlation of the

dimensions |

100% (****) |

|

Bardus et al. |

2020 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Translating, adapting and

validating the MARS scale in Arabic |

MARS-Ar scale. Good

internal consistency: α = .96 (engagement), .94 (aesthetics), .81

(quality of information) and .71 (functionality). Good inter-rater

reliability: ICC =.83. Scale highly aligned with the original version |

100% (****) |

|

Llorens-Vernet and Miró |

2020 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Validating the MAG guide |

A total of 48 final

criteria were established (Delphi method). Usability, privacy and security

were the dimensions that included the most relevant criteria |

75%(c) (***) |

|

Messner et al. |

2020 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Translating, adapting and

validating the MARS scale in German |

MARS-G scale. Good internal

consistency: Omega = range .72-.91. High inter-rater reliability: ICC =.83.

High values in the correlation of the dimensions. Scale excellently aligned

with the original version |

100% (****) |

|

Terhorst et al. |

2020 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Validating the MARS guide |

The CFA generated a bifactorial

model with a general factor and a factor for each dimension. Good/excellent

internal consistency: Omega = range .79-.93. High inter-rater reliability:

ICC =.82. High values in the correlation of MARS with the Enlight tool |

100% (****) |

|

Saliasi et al. |

2021 |

Descriptive quantitative |

Translating, adapting and

validating the MARS scale in French |

MARS-F scale. Acceptable

internal consistency: Omega = .79 (engagement), .79 (functionality), .78

(aesthetics) and .61 (quality of information). High values in the correlation

of the dimensions. Scale well aligned with the original version |

100% (****) |

|

Notes: (a) The method of allocation concealment or

post-randomisation blinding is not specified. (b) There is a perceived lack of justification for

the relevance of the sample size (pilot test). (c) The reasons why certain eligible subjects

decided to not participate in the Delphi rounds are not explained. |

|||||

|

CFA - Confirmatory factor analysis. ICC - Intraclass correlation coefficient. MAG – Mobile App Development and Assessment

Guide. MARS - Mobile App Rating Scale. MMAT - Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. n.p. - Not provided. |

|||||

All dimensions and indicators used in these articles

were then extracted, resulting in 59 dimensions and 282 indicators in total.

After eliminating duplicates and merging similar dimensions and indicators, the

final list was made up of a total of 97 indicators grouped into 17 dimensions

(Table 3). In order to clearly delimit

the specificity of each dimension, a detailed explanation/description of what

they contain has been made. This information hasn’t been included in this

document due to lack of space, but it can be obtained from the people in charge

of the study.

Table 3

List of dimensions considered

|

Dimensions |

|

|

1. Engagement/Participation |

10. Technical support and updates |

|

2. Functionality (technical/technology) |

11. Psychotherapy |

|

3. Functionality (usability) |

12. Psychotherapy (usability) |

|

4. Functionality (accessibility) |

13. Safety of use |

|

5. Aesthetic/ Visual design |

14. Quality/Subjective assessment |

|

6. Information |

15. Quality/Subjective assessment

(predisposition) |

|

7. Information (scientific basis) |

16. Therapeutic persuasion |

|

8. Information (ethics) |

17. Therapeutic alliance |

|

9. Privacy/Data security |

|

4. Discussion

Firstly, regarding the bibliometric analysis carried

out, it has been observed that the date of publication of documents related to

the topic being studied began in 2015; this shows that the evaluation of apps

in the field of mHealth is a recent topic of interest in terms of scientific

literature, coinciding with the results obtained in other studies

(Azad-Khaneghah et al., 2021; Nouri et al., 2018). Germany and Australia are

the countries where the majority of the studies on this topic have been carried

out.

In line with studies such as Azad-Khaneghah et al.

(2021), it is striking to note the large number of papers that refer to the

MARS scale as the first tool to measure the quality of health apps. Although it

has been adapted into different languages and versions, and has gained obvious

recognition in the scientific community (Bardus et al., 2020; Böhme et al.,

2019; Domnich et al., 2016; Martín-Payo et al., 2019; Messner et al.,

2020; Saliasi et al., 2021; Stoyanov et al., 2016), there are some shortcomings,

as no dimensions or indicators related to privacy and security issues are

included; conclusions that were also reached by Hensher et al. (2021) and

Jeminiwa et al. (2019).

According to the results of the systematic study

conducted by Duarte-Hueros et al. (2021) on the Spanish quality accreditation

initiatives and their regulatory processes in health apps, it has been observed

that the indicators, criteria and recommendations contained in such initiatives

have relevant similarities with this review.

Many of the recommendations of the AppSaludable

label and the criteria of the Acreditació

FTSS certification service appear among the results presented here.

Although there are some overlaps, the terminology used is broadly different.

Furthermore, a significant aspect of these initiatives

is that variables related to privacy and security are assessed; two dimensions

that, in this case and unlike most of the evaluation instruments analysed, have

been considered and conveniently described in this study.

5. Conclusions

According to the data obtained from the MMAT tool in

relation to the methodological design followed in the studies analysed, it can be

concluded that research in this area has mostly been approached from a

descriptive quantitative perspective, showing a noteworthy methodological

quality: the 11 articles met at least 75% of the criteria set out in the tool.

Based on the different dimensions and common

indicators identified in the studies analysed, and the information contrasted

with other documents, this research is the starting point for the construction

of a framework for the evaluation of app quality, especially considering that

the scales/instruments currently available are not oriented towards the

evaluation of apps for the general population (Azad-Khaneghah et al., 2021) or

apps that promote/develop healthy habits.

None of the studies include clear

descriptions/explanations of each dimension. In this respect, this research is

novel, as an effort has been made to make them more comprehensible and to

improve their alignment with the related set of indicators.

In terms of limitations of the study, the changing and

dynamic nature of technology should be borne in mind, and it is therefore

recommended that the dimensions and indicators identified be reviewed at

regular intervals. In this sense, despite having consulted databases of high

scientific impact (Web of Science, Scopus, PubMed and Cochrane Library), we

have avoided indexing in other databases where valuable literature on the

subject under study could be found.

With a view to the future, it is suggested that

studies with controlled methodological designs should be developed which, in

turn, could provide an in-depth explanation of each dimension and indicator, as

well as including categories related to privacy and security as part of a

comprehensive assessment of any app.

6. Funding

This work has been supported by the Research and Transfer

Policy Strategy of the University of Huelva (predoctoral grants for Research

Staff in Training, 2020).

References

Aitken, M. & Nass,

D. (2021). Digital Health Trends 2021: Innovation, evidence, regulation, and

adoption. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. https://bit.ly/33sHF9k

Azad-Khaneghah, P., Neubauer,

N., Cruz, A. M. & Liu, L. (2021). Mobile health app usability and quality

rating scales: a systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive

Technology, 16(7), 712-721. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1701103

Bardus, M., Awada, N.,

Ghandour, L. A., Fares, E., Gherbal, T., Al-Zanati, T. & Stoyanov, S. R.

(2020). The Arabic Version of the Mobile App Rating Scale: Development and

Validation Study. JMIR MHealth Uhealth, 8(3), e16965. https://doi.org/10.2196/16956

Baumel, A., Mathur, N., Kane,

J. M. & Muench, F. (2017). Enlight: A Comprehensive Quality and Therapeutic

Potential Evaluation Tool for Mobile and Web-Based eHealth Interventions. Journal

of Medical Internet Research, 19(3), e82. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7270

BinDhim, N. F., Hawkey, A.

& Trevena, L. (2015). A Systematic Review of Quality Assessment Methods for

Smartphone Health Apps. Telemedicine and e-Health, 21(2), 97-104. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0088

Böhme, C., von Osthoff,

M. B., Frey, K. & Hübner, J. (2019). Development of a Rating Tool for

Mobile Cancer Apps: Information Analysis and Formal and Content-Related

Evaluation of Selected Cancer Apps. Journal of Cancer Education, 34(1),

105-110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1273-9

Boudreaux, E. D., Waring, M.

E., Hayes, R. B., Sadasivam, R. S., Mullen, S. & Pagoto, S. (2014).

Evaluating and selecting mobile health apps: strategies for healthcare

providers and healthcare organizations. Translational Behavioral Medicine,

4(4), 363-371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0293-9

Collado-Borrell,

R., Escudero-Vilaplana, V., Villanueva-Bueno, C., Herranz-Alonso, A. &

Sanjurjo-Sáez, M. (2020). Features and Functionalities

of Smartphone Apps Related to COVID-19: Systematic Search in App Stores and Content

Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e20334. https://doi.org/10.2196/20334

Coyne, E., Rands, H.,

Frommolt, V., Kain, V., Plugge, M. & Mitchell, M. (2018). Investigation of

blended learning video resources to teach health students clinical skills: An

integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 63, 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.021

Domnich, A., Arata, L.,

Amicizia, D., Signori, A., Patrick, B., Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., Gasparini,

R. & Panatto, D. (2016). Development and validation of the Italian version

of the Mobile Application Rating Scale and its generalisability to apps targeting

primary prevention. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16(83).

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0323-2

Duarte-Hueros,

A., Delgado-Morales, C. & Field-Cabezas, N. (2021). Estudio sistemático

sobre distintivos y sellos de calidad de aplicaciones móviles para la formación

en hábitos saludables. En J. Ruiz-Palmero, E. Sánchez-Rivas, E. Colomo-Magaña

& J. Sánchez-Rodríguez (Coords.), Innovación e investigación con

tecnología educativa (pp. 105-116). Octaedro.

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A.

(2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated

methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Hensher, M., Cooper, P., Dona,

W. A., Angeles, M. R., Nguyen, D., Heynsbergh, N., Chatterton, M. L. &

Peeters, A. (2021). Scoping review: Development and assessment of evaluation

frameworks of mobile health apps for recommendations to consumers. Journal

of the American Medical Informatics Association, 28(6), 1318-1329. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocab041

Jake-Schoffman, D. E., Silfee,

V. J., Waring, M. E., Boudreaux, E. D., Sadasivam, R. S., Mullen, S. P., Carey,

J. L., Hayes, R. B., Ding, E. Y., Bennett, G. G., & Pagoto, S. L. (2017).

Methods for evaluating the content, usability, and efficacy of commercial

mobile health apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 5(12), e8758. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8758

Jeminiwa, R. N., Hohmann, N.

S. & Fox, B. I. (2019). Developing a Theoretical Framework for Evaluating

the Quality of mHealth Apps for Adolescent Users: A Systematic Review. The

Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 24(4), 254-269. https://doi.org/10.5863/1551-6776-24.4.254

Lee, C. Y. & Cherner, T.

S. (2015). A Comprehensive Evaluation Rubric for Assessing Instructional Apps. Journal

of Information Technology Education: Research, 14, 21-53. https://doi.org/10.28945/2097

Llorens-Vernet, P. &

Miró, J. (2020). The Mobile App Development and Assessment Guide (MAG):

Delphi-Based Validity Study. JMIR MHealth Uhealth, 8(7), e17760. https://doi.org/10.2196/17760

Martín-Payo,

R., Fernández-Álvarez, M. M., Blanco-Díaz, M., Cuesta-Izquierdo, M., Stoyanov,

S. R. & Llaneza-Suárez, E. (2019). Spanish

adaptation and validation of the Mobile Application Rating Scale questionnaire.

International Journal of Medical Informatics, 129, 95-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.06.005

Messner, E., Terhorst, Y.,

Barke, A., Baumeister, H., Stoyanov, S. R, Hides, L., Kavanagh, D. J., Pryss,

R., Sander, L. & Probst, T. (2020). The German Version of the Mobile App

Rating Scale (MARS-G): Development and Validation Study. JMIR MHealth

Uhealth, 8(3), e14479. https://doi.org/10.2196/14479

Moher, D., Liberati, A.,

Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G. & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred Reporting

Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS

Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Nouri, R., Niakan-Kalhori, S.

R., Ghazisaeedi, M., Marchand, G. & Yasini, M. (2018). Criteria for

assessing the quality of mHealth apps: a systematic review. Journal of the

American Medical Informatics Associations, 25(8), 1089-1098. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy050

Organización

Mundial de la Salud. (2011). mHealth: new

horizons for health through mobile technologies: second global survey on

eHealth. Global Observatory for eHealth. https://bit.ly/3LV8iVu

Palacios-Gálvez,

M. S., Yot-Domínguez, C. & Merino-Godoy, Á. (2020). Healthy Jeart:

promoción de la salud en la adolescencia a través de dispositivos móviles. Revista

Española de Salud Pública, 94, e202003010. https://doi.org/10.4321/S1135-57272020000100008

Pluye, P., Robert, E., Cargo,

M., Bartlett, G., O’Cathain, A., Griffiths, F., Boardman, F., Gagnon, M. P.

& Rousseau, M. C. (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for

systematic mixed studies reviews. McGill University. https://bit.ly/3EVOC0f

Powell, A. C., Landman, A. B.

& Bates, D. W. (2014). In Search of a Few Good Apps. JAMA, 311(18),

1851-1852. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.2564

Saliasi, I., Martinon, P.,

Darlington, E., Smentek, C., Tardivo, D., Bourgeois, D., Dussart, C., Carrouel,

F. & Fraticelli, L. (2021). Promoting Health via mHealth Applications Using

a French Version of the Mobile App Rating Scale: Adaptation and Validation

Study. JMIR MHealth Uhealth, 9(8), e30480. https://doi.org/10.2196/30480

Schulz, K. F. & Grimes, D.

A. (2002). Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. The Lancet,

359(9307), 696-700. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07816-9

Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L.,

Kavanagh, D. J. & Wilson, H. (2016). Development and Validation of the User

Version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (uMARS). JMIR MHealth

Uhealth, 4(2), e72. https://doi.org/10.2196/mHealth.5849

Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L.,

Kavanagh, D. J., Zelenko, O., Tjondronegoro, D. & Mani, M. (2015). Mobile

App Rating Scale: A New Tool for Assessing the Quality of Health Mobile Apps. JMIR

MHealth Uhealth, 3(1), e27. https://doi.org/10.2196/mHealth.3422

Terhorst, Y., Philippi, P.,

Sander, L. B., Schultchen, D., Paganini, S., Bardus, M., Santo, K., Knitza, J.,

Machado, G. C., Schoeppe, S., Bauereiß, N., Portenhauser, A., Domhardt, M.,

Walter, B., Krusche, M., Baumeister, H. & Messner, E. M. (2020). Validation

of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS). PLoS ONE, 15(11),

e0241480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241480

Willis, S., Neil, R., Mellick,

M. C. & Wasley, D. (2019). The Relationship Between Occupational Demands

and Well-Being of Performing Artists: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in

Psychology, 10(393). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00393