The use of ChatGPT in

academic writing: A case study in Education

The use of ChatGPT in academic writing: A case study in

Education

D. Kevin Baldrich. Contratado predoctoral. Universidad de

Almería. España

D. Kevin Baldrich. Contratado predoctoral. Universidad de

Almería. España

Dra. Juana Celia Domínguez-Oller. Profesora sustituta interina. Universidad

de Almería. España

Dra. Juana Celia Domínguez-Oller. Profesora sustituta interina. Universidad

de Almería. España

Recibido:

2023/12/21 Revisado 2024/01/08 Aceptado: :2024/07/04 Online First: 2024/07/12 Publicado: 2024/09/01

Cómo citar este artículo:

Baldrich

, K., &

Domínguez-Oller, J. C. (2024). El uso de ChatGPT

en la escritura académica: Un estudio de caso en educación [The

use of ChatGPT in academic writing: A case study in Education]. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, 71, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.103527

ABSTRACT

Academic Literacy faces new

challenges with the emergence of Artificial Intelligence, specifically in the

field of university academic writing. This study investigates the impact of

ChatGPT on the quality of academic work from 33 students (7 groups) in Early

Childhood Education. The project was developed in three phases, through a

descriptive case study with a qualitative approach, consisting of: 1) an

initial assessment using a closed ad hoc survey to understand experiences prior

to using ChatGPT, 2) a comparative analysis of academic work with and without

ChatGPT using a rubric and a comparative table, 3) an ad hoc open-ended survey

to understand project experiences, later categorized with Atlas.ti

software. The results reveal improvements in writing such as coherence,

cohesion, academic language, but also certain deficiencies. It is concluded

that ChatGPT can serve as a supplement to academic work, being more effective

when students already have a foundation in critical, ethical, and argumentative

skills.

RESUMEN

La Alfabetización académica enfrenta nuevos retos con

la emergencia de la Inteligencia Artificial, concretamente en el ámbito de la

escritura académica universitaria. Por ello, este estudio investiga el impacto

de ChatGPT en la calidad de los trabajos académicos

de 33 estudiantes (7 grupos) del Grado de Educación Infantil. El proyecto se

desarrolló en tres fases, mediante un estudio de caso descriptivo con enfoque

cualitativo, que consistió en: 1) una evaluación inicial mediante una encuesta

ad hoc cerrada para conocer las experiencias previas al uso de ChatGPT 2) un análisis comparativo de trabajos académicos

con y sin ChatGPT analizado mediante una rúbrica y

una tabla comparativa 3) una encuesta ad hoc de preguntas abiertas para conocer

las experiencias del proyecto que posteriormente se categorizaron con el

Software Atlas.ti. Los resultados revelan mejoras en

la escritura de los trabajos como en coherencia, cohesión, lenguaje

académico... pero también ciertas deficiencias. Se concluye que ChatGPT puede servir como complemento de trabajos

académicos, siendo más efectivo cuando los estudiantes ya poseen una base en

habilidades críticas, éticas y argumentativas

PALABRAS CLAVES· KEYWORDS

Artificial intelligence; academic literacy; case

study; ChatGPT; written argumentation

Inteligencia artificial; alfabetización académica;

estudio de caso; ChatGPT; argumentación escrita

1. Introduction

New challenges and

opportunities for academic contexts emerge as new technologies become embedded

in society. In this scenario, academic literacy represents an evolving concept

that encompasses critical competencies for effective student participation in

university communities (Guzmán-Simón & García-Jímenez, 2015). At its core,

academic literacy focuses on the ability to understand and produce disciplinary

texts, a process that goes beyond the simple decoding of information to

encompass participation in socially recognised knowledge practices (Carlino,

2013; Maldonado et al., 2023). This approach has undergone a notable shift from

teaching decontextualised reading and writing skills to more situated

approaches that promote immersion in the discourses specific to each field of

knowledge (Padilla & Carlino, 2010).

In this context, written

argumentation plays a crucial role, since, through its discursive strategies,

individuals can actively contribute to the construction of knowledge (Archila,

2015; Villarroel et al., 2019). Argumentation allows students not only to

present their ideas, but also to defend, refute and situate them within a

broader context, thus contributing to the advancement of knowledge (Bañales et al., 2015). In this sense, argumentation allows

for the development of critical thinking and the evaluation of assertions,

fundamental components in academia where enquiry and validation of information

are fundamental aspects (Kriscautzky & Ferreiro,

2018; Lara et al., 2022).

Teaching written

argumentation, as Villanueva et al. (2022) point out, is a complex process that

requires fostering both writing skills and logical and critical thinking in

students. Not being innate, this skill needs intentional learning and practice

(Bañales et al., 2015 and Molina & Carlino,

2013). Otherwise, students may face a significant disconnect between their

expectations and the practical skills required in their training, as suggested

by Toledo (2019). For that reason, the multiplicity and variability of

discursive genres in academia, according to the different disciplines, implies

a challenge for teachers to identify and explicitly teach the specific

characteristics of the texts required in each area (Moore & Mayer, 2016;

Navarro, 2019).

Academic literacy also

involves the development of digital reading and writing skills. In the

information age, intertextuality and networked reading have become

indispensable skills (Hernández et al., 2018; Martinez-Gamboa, 2016 and Caro et

al., 2023). The ability to adequately cite and argue on digital platforms

becomes an indicator of advanced academic literacy. The transition towards the

use of digital tools in writing represents a significant leap in this scenario.

For example, Mateo-Girona et al. (2021) highlight how digital tools and current

contexts can lead to an improvement in argumentative writing skills.

Therefore, educators face

the task of teaching writing in an ever-changing digital environment, where the

lines between formal and informal writing become increasingly ambiguous

(Cassany, 2019). There is a need to educate students on how to write for different

audiences and the use of different 'voices' and 'registers'. However, digital

tools can lead students to opt for quicker solutions and not to put enough

effort into their writing (García & Fernández, 2015 and Cisneros-Barahona

et al., 2023).

In this perspective,

artificial intelligence (AI) emerges as a potential driver of change in

education, whereby the learning experience is personalised and enriched (Aler

et al. 2023). This technology not only transforms the way learners access and

use content, but also facilitates a more interactive approach tailored to their

individual needs (Gómez, 2023; Ruaro & Reis, 2020). The integration of AI

in educational processes transcends simple automation, in which a deeper and

more meaningful engagement of students with the study material is fostered

(Gómez, 2023; González & Romero, 2022 and Ocaña-Fernández et al., 2019;

Prieto-Andreu and Labisa-Palmeira, 2024; Leong et al., 2023).

This transformation goes

beyond conventional methodologies. Recent research, such as that conducted by

Limo et al. (2023), Dwivedi et al. (2023) and Akiba and Fraboni (2023), shows

how ChatGPT can provide personalised feedback to students and play a tutor-like

role in academic contexts. These studies highlight that more than 60% of

students use this tool for specific academic assignments. Moreover, the

functionality of ChatGPT is not limited to tutoring; it can also enhance the

learning process and foster the development of critical skills, such as

argumentative competences (Acevedo, 2023; Martínez-Comesaña,

2023; Vera, 2023). In addition, Woo et al. (2023) evaluate the effectiveness of

ChatGPT in supporting non-native learners of English, concluding that it has

enormous potential to facilitate the development of written communicative

skills. Consequently, the transformation of pedagogy and the educational

experience driven by this technology is a testament to the impact that AI has

and can have on the education sector (Calle & Mediavilla, 2021; Chicaíza et al., 2023).

As well as the benefits,

there are challenges associated with the use of AI in education (Selwyn et al.,

2022). It is essential to maintain a balance between technology and human

interaction, as education also involves the development of social and emotional

skills (Leão et al., 2022). Furthermore, Ruaro and Reis (2020), Degli-Esposti

(2021) and Barrios-Tao et al. (2021) warn about the need to address AI biases,

ethical use of data and privacy, as well as the implications of AI management

on human autonomy. In this sense, the integration of new literacies, including

digital and media literacies, becomes an imperative for an education that must

prepare students for a world where argumentation and effective communication

are more important than ever and students are shaped as participatory,

critical, creative and ethical citizens (Difabio de Anglat & Álvarez, 2017).

However, it should be noted

that this research is exploratory in nature since, due to the novelty of this

emerging technology, there are hardly any specific antecedents that accurately

contextualise the problem addressed in this study and dimension the real scope

of our findings. For that reason, the purpose of this research is to test

whether ChatGPT can be an effective tool for improving academic work already

produced by students. This general purpose is divided into the following

specific objectives:

·

To assess students' prior

ideas about the use of ChatGPT as a suitable tool for developing written

composition.

·

To compare the differences

between the texts produced by students before and after the incorporation of

ChatGPT.

·

To explore students'

perceptions of the use of ChatGPT in their process of developing the

theoretical framework.

2. Methodology

In order to achieve the objectives set out in this study, a qualitative approach was

adopted through a descriptive case study. This methodology was selected for its

ability to provide a detailed and contextualised analysis of students'

experiences and perceptions in relation to the development of a theoretical

framework and the use of ChatGPT. According to Yin (2009), descriptive case

studies are effective in analysing and understanding the 'what', 'who', 'where'

and 'how' of a specific phenomenon, which is ideally suited to meet the objectives

of this research. This approach allows for an in-depth understanding of

individual and group dynamics in the use of technological tools in education.

2.1.

Participants

Seven groups of 4 to 5

members each from the third year of the Degree in Early Childhood Education at

the University of Almeria, aged between 20 and 29 years (3 men and 29 women)

participated. They were selected from a subject on Development of oral

communication skills and their didactics. They were informed about the confidentiality

of their data and the objectives of the research, in accordance with the Code

of Good Research Practices of the University of Almeria (2011).

2.2. Instruments

A variety of instruments

were used in the research to collect and analyse the data obtained, with each

one fulfilling a specific and complementary role. Initially, a participant

observation method was adopted, based on the principles established by Taylor

and Bodgan (1984). This allowed for a direct

immersion in the educational environment to closely observe the students' work

process. The observation focused on the construction of theoretical frameworks

related to the subject matter. After this, the academic material produced by

the students was analysed on the basis of the

dimensions established by Guadarrama (2008): historical-contextual, conceptual

and methodological. This process involved the review of academic works before

and after the introduction of ChatGPT to focus attention on changes in the

structure, coherence and quality of the theoretical frameworks (de la Peña

& Cortés, 2018).

To complement these methods,

questionnaires were used at two key stages of the study (de la Cuesta-Benjumea,

2008). It began with an ad hoc closed-ended questionnaire that provided

information on students' perceptions and prior experiences with academic writing

and artificial intelligence. This initial phase was necessary to establish a

baseline of students' attitudes and prior knowledge. Once ChatGPT was used in

the development of the proposed assignments, an ad hoc open-ended questionnaire

was administered with a qualitative and exploratory approach (Jansen, 2013) in

order to gain a more detailed understanding of the students' experiences after

using ChatGPT with questions adapted from (Sanchez, 2023) to find out about

challenges or limitations, experiences, effectiveness in reviewing group

assignments, specific examples about its usefulness in the work, among others.

The combination of

participant observation, analysis of academic papers and questionnaires at

different stages of the study aims to ensure that data collection and analysis

is complete and varied (Aranda and Araújo, 2009).

2.3. Investigation procedure

The study procedure was

structured in the following phases (Table 1):

Table 1

Phases of the study

|

Phase |

Description |

|

Phase

1: Observation and initial evaluation |

Observation

of the academic work process in the development of theoretical frameworks

related to the subject content (language components), followed by initial

data collection through questionnaires to assess students' perceptions and

prior experiences in academic writing and artificial intelligence, in order

to establish a benchmark for future comparisons. |

|

Phase

2: ChatGPT implementation |

Introduction

and explanation of ChatGPT to students as a complementary tool in their

academic work, accompanied by the collection of data on student interaction

with ChatGPT to monitor its impact on the development of theoretical

frameworks. |

|

Phase

3: Comparison and final evaluation |

Preliminary

comparative analysis of academic papers before and after the incorporation of

ChatGPT, followed by the use and adaptation of the de la Peña and Cortés

(2018) argumentative text evaluation rubric, and the analysis of the

post-ChatGPT questionnaire using Atlas.ti. |

2.4. Data analysis

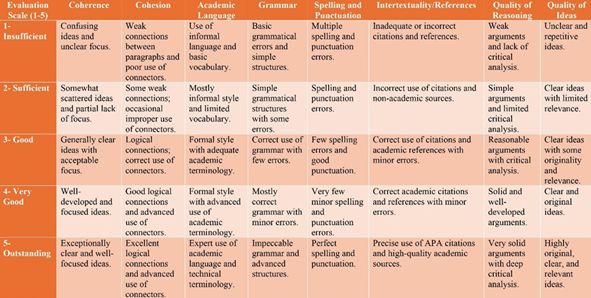

In the data analysis of this

research, the closed-ended questionnaire collected through Google Forms was

examined to understand students' prior perceptions and skills in academic

writing and technology use. This was followed by a comparative table analysis

of the students' work, both before and after the use of ChatGPT. This analysis

focused on key variables developed from the contributions of Peña and Cortés

(2018) and the rubric (Figure 1) of Ramos (2018). These are focused on the use

of sources and citations, level of formality, critical analysis, discursive

structures, academic vocabulary and metalinguistic awareness. Therefore, the

papers were analysed independently of those that had been carried out with ChatGPT

to avoid bias in the evaluation and to ensure an objective assessment based on

the established criteria (Gerring, 2017). Finally, the final survey data

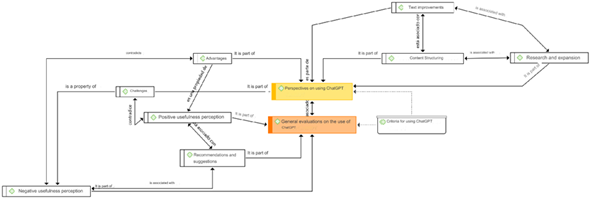

analysis was carried out using emergent coding through the method described by

de la Espriella and Gómez (2020). This approach involves a detailed examination

of student responses to identify meanings and patterns. Two researchers coded

the data independently and then merged their codes to solicit the opinion of a

third researcher in cases of discrepancies. This process was complemented by

the use of ATLAS.ti software (Version 23.1.0, ATLAS.ti Scientific Software

Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany), which facilitated the organisation of

categories and the construction of a network of relationships between them.

3. Results

Prior to introducing ChatGPT

into the educational process, a survey was conducted to assess students'

perceptions and writing skills in relation to Artificial Intelligence. The

results showed that 35% of the students were familiar with the concept of ChatGPT,

while 31% were less familiar with this artificial intelligence tool, indicating

a significant difference. In terms of satisfaction with their writing and

argumentation skills, the majority (62%) are confident in their current

competences. However, when it comes to difficulties in writing academic texts,

almost half of the participants (48 %) did not encounter any obstacles, which

could be evidence of a solid foundation of writing skills among the

respondents. On the other hand, a considerable proportion of students (42%)

considered that AI could be a useful tool to improve their writing; this

suggests an openness towards incorporating new technologies in their learning.

After the initial survey,

the students produced their work without the use of the tool and subsequently

used it to improve the written product. For this reason, in order to assess the

impact of this tool, it was analysed through a rubric developed for this

research, whose variables are adapted to the dimensions addressed by de la Peña

and Cortés (2018), Guadarrama (2008) and Ramos (2018) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Evaluation rubric

Note: Prepared by the authors and adapted from research by de la Peña and

Cortés (2018), Guadarrama (2008) and Ramos (2018).

In carrying out the

comparative analysis, the WG6 group, working with ChatGPT, presented a logical

sequence of ideas focused on the concept of "Syntax". This group

dealt with topics such as the definition of syntax, its importance in

communication, the relevance of syntax today and its influence on digitisation.

Despite some areas for improvement, their sequence was coherent and stable as

reflected in the rubric. In contrast, the WG5 group, when dealing with

Phonetics, focused on defining what phonetics is and its importance in the

educational context. Regarding cohesion, the WG5 group went from not using

discourse markers to their use as "However, on the other hand..." but

the composition and abuse of these detracts from the linear writing in which

they make use of 1 marker every 2 lines. In the use of academic language, WG6

evolved from colloquial terms to more technical language, such as "social

phenomena" instead of "things". In terms of grammar, WG2 showed

a notable improvement in the variety of syntactic structures with ChatGPT,

although concordance errors and the abuse of gerunds persisted, a structure

that does not correspond to Spanish linguistic norms, such as "narrating,

telling, developing and collaborating" appearing in the same 4-line

paragraph. In spelling, WG3 corrected errors such as "valla/vaya",

but still had lapses in punctuation, an aspect repeated in all groups in

different ranks. Furthermore, with regard to references, WG4 included some that

corresponded to APA 7 guidelines, while WG7 still showed errors in textual

citations such as "Morris in (1985), defined the pragmatic dimension of

semiology with the following words:...". It should be underlined that all

groups used an average of 2 to 5 authors. In quality of reasoning, WG4 and WG3

improved in the substantiation of arguments with the tool, although it did not

completely eliminate speculation. On the contrary, WG1 detailed its contents in

sections with the constant use of hyphens and the abuse of copying direct

sentences from ChatGPT.

Once the papers had been

analysed, a post-evaluation was carried out to find out the students'

perspectives on their experience with the tool, during and after the

development of the paper. Below is a table (table 2) with the categories and

subcategories, which includes examples of the groups for each subcategory:

Table 2

Codificación y categorización de organización en Atlas.ti

|

Category |

Subcategory |

examples

of responses |

|

Perspectives

on using ChatGPT |

Structuring

content |

WG1:

"In our case, we used it to structure the script of the podcast, as we

are quite inexperienced in this field and it helped us a lot by proposing

greetings, catchphrases that engage the receiver and farewells". |

|

|

Textual

improvements |

WG3: "Once the theoretical framework was

laid out, we asked him what we could do better to complete it and make the

most of the information we had". WG6:

"It was effective in the sense that it transcribed some text better than

what we already had, but I am not a big fan of using Artificial Intelligence". |

|

|

Research

and extension |

WG2: "We used chatGpt to find out more

about the topic we were working on, we asked him and he told us what he knew

about it, some things seemed interesting to us and we attached them to the

work, but merely as a complement to the work we had already done

beforehand". WG3: "We used it by directly consulting

those sections of our work that we thought could be expanded and/or

perfected, that is, we wanted to extract more information from some specific

points of our work [...]" |

|

|

Challenges |

WG2: "At the beginning we didn't really

know how to use it or the possibilities that the platform offered". WG6: Quite a lot, because some of the more

specific AIs are only designed for English and other languages, but not for

Spanish. |

|

|

Advantages |

WG2: "It was quite effective in terms of

broadening my knowledge". |

|

General

evaluations on the use of ChatGPT |

Perception

of positive utility |

WG1: "I think it would be interesting to

incorporate ChatGPT as another tool when working in the classroom". WG4: "In our opinion, we think that using

ChatGPT as another resource is good for learning to contrast information

and/or detect reliable sources from unreliable ones [...]" WG7: "That it is a good tool to rely on in

certain grammatical, structural and discursive aspects". |

|

|

Negative

utility perception |

WG6: "I have only used Chat GPT twice and I

still don't think it's a very good idea to use this tool because I think it

takes away a lot of work and from my point of view we can't let that happen

because the creativity and originality of a lot of content [...]". |

|

|

User

satisfaction |

WG5: "It should be just a support, the

professionals should be dedicated to squeeze their ideas", WG2: "In our case we have nothing to add in

terms of improvements, but for those who use it to copy and paste, it would

be interesting to be able to make an initial delivery without using chatGpt

and then give the possibility to extend it [...]", WG4: "We were a

bit more lost when it came to cross-checking information [...]", WG5:

"We were a bit more lost [...]". WG4: "When it came to cross-checking the

information we were a bit more lost.... We would like to know how or what

steps to follow to detect the veracity of information given by ChatGPT". |

Figure 2

Network of relationships between categories

Note. Own elaboration

One of the most valued

applications of ChatGPT has been its ability to assist in structuring and

improving texts. Groups such as WG3 and WG7 recognise its usefulness in

enhancing theoretical frameworks and completing sections of papers. However,

there is also a concern about over-reliance on technology, as WG6 put it:

"It was effective in the sense that it transcribed some text better than

what we already had, but I'm not a big fan of using AI". In terms of

research, several groups have used ChatGPT to expand their knowledge on

specific topics. WG2 comments on how they used the tool to gain additional

information on their topic of study: "We used chatGPT to further inform

ourselves about the topic at hand". However, the integration of ChatGPT

into academic research is not without challenges, such as the language barriers

mentioned by WG4. Perceptions of the usefulness of ChatGPT vary considerably

between the groups. WG1 and WG7 highlight its value in grammatical, structural

and discourse aspects. On the other hand, WG6 offers a more critical

perspective, warning about the risks of over-dependence on technology: "I

have only used Chat GPT twice and I still think that I don't think it is a very

good idea to use this tool". In the face of these diverse experiences and

perceptions, subjective evaluations emerge from the participants on the

usefulness and ease of use of ChatGPT tools. WG5 suggests that ChatGPT should

be a support and not a substitute for critical thinking and creativity. In

addition, the need to verify the information provided by ChatGPT is a recurring

theme. WG4 stresses the importance of learning how to cross-check information

and identify reliable sources.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The analysis of the results

of this study reveals a notable influence of ChatGPT on the quality of written

argumentation in academic contexts. It is observed that some groups experienced

a significant improvement in terms of textual coherence and cohesion, while

others continued to experience certain difficulties associated with discursive

organisation. This disparity makes explicit the need to reinforce the teaching

of critical argumentation skills, as reflected by Sánchez (2023), given that

reliance on technological tools such as ChatGPT could mask basic deficiencies

in essential writing skills. Given this circumstance, it would be advisable to

provide specific training for teachers in the didactic use of artificial

intelligence tools and thus minimise the risks of superficial use that is alien

to the specific competences that students should attain (Simó et al., 2020).

In addition to this,

deficits were observed in the control and validation of the information

obtained through ChatGPT. Our findings are in line with those obtained by Zhu

et al. (2023) for whom students often do not know how to contrast or verify the

information provided by these tools. Ortiz (2023) suggests that, although

ChatGPT 3.5 is useful for reviewing material and producing constructive

writing, it is not suitable for creating original projects from scratch. This

is evidence of the need for human intellectual input into knowledge generation

and for policies to regulate the veracity of data produced by artificial

intelligence systems.

However, additional

research, such as that of Bishop (2023), Gutierrez et al. (2023) and Wang and

Xu (2023), presents a more positive picture of ChatGPT's potential for writing

improvement. These studies show remarkable improvements in written argumentation.

As observed in some of the groups analysed in our research, the use of ChatGPT

has facilitated greater fluency and cohesion in the use of discourse

connectors, argumentative structures and clarification of ideas, thus

demonstrating its value as a complementary tool. Nevertheless, the results

corroborate the findings of Carrera et al. (2019), which confirm a discrepancy

between university students' self-perception of their writing skills and the

quality of their first papers. Despite the fact that more than half of them

claim to possess the necessary skills for effective written argumentation,

their initial submissions reflect the opposite.

The study also highlights

ethical concerns related to the use of ChatGPT, particularly with

regard to academic integrity and originality. The variability in the

perception of its usefulness and ethics, observed in the different groups

studied, highlights the need to focus on issues such as authorship and academic

honesty. Atencio-González et al. (2023) and Vera et al. (2023) emphasise that

most groups chose to copy directly from ChatGPT without making significant

modifications or with the intention of simply transcribing the contents. This

highlights the problem of plagiarism and the lack of motivation to explore new

possibilities that could enrich the educational process. Similarly, it is

important to recognise that the use of tools such as ChatGPT should not replace

the author's original work, but serve as a support.

Vicente-Yagüe-Jara et al. (2023) highlight

that students understood that their role is to complement and not to replace

the intellectual effort in the creation of original work and also that instead

of prohibiting the use of these tools, the focus should be on adequate control

of them.

Therefore, this study shows

the need to analyse and guide students in the incorporation of tools such as

ChatGPT in academic contexts. It highlights the importance of finding a balance

between the adoption of new technologies and the preservation of fundamental

educational objectives. The observed variability in the quality of students'

written argumentation points to the need to emphasise the development of these

skills from the early years of university, as suggested by Malinka et al.

(2023). Furthermore, Perkins' (2014) analysis stresses the need to cultivate

fundamental skills before introducing advanced tools such as ChatGPT. This

perspective, aligned with Melo-Solarte & Díaz (2018), indicates that

engagement and entertainment should not be confused with effective learning as

ignorance and inadequate implementation of methodologies and tools in the

classroom, if not addressed correctly, can have unsuccessful results.

Therefore, the integration of technology must be careful, adapting to the

specific needs of students and promoting a balanced approach that fosters both

student engagement and the development of critical skills, as

Vicente-Yagüe-Jara (2023) points out.

In view of this, it should

be noted that, although tools such as ChatGPT have the potential to improve the

quality of written argumentation, it is essential that they are properly

integrated into the planning of the educational curriculum. This implies designing

specific teacher training programmes that train educators in the didactic use

of these tools and promote their reflective and critical use among students.

Consequently, future research should focus on exploring effective methods for

the implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in education,

assessing not only their impact on academic performance, but also on the

development of competency skills such as critical thinking and the ability to

contrast information. In this way, it can be ensured that artificial

intelligence tools complement, rather than replace or rely on, the necessary

competences that students need to perform successfully in their academic and

professional futures (Ortiz, 2023).

It is important to note that

this study has several limitations. First, the small number of participants

makes it difficult to generalise the results. In addition, the surveys used

have not been validated, largely due to the lack of previous research in this

new area yet to be explored in depth. It is therefore essential for future

research to carry out empirical research in real educational settings. These

studies should focus on assessing students' reading and writing skills in order

to determine their ability to handle and benefit from the use of tools such as

ChatGPT. This practical analysis will allow us to adapt the teaching of these

technologies and ensure that they correspond to the current competencies of the

student body (Meana, 2018).

In conclusion, this research

shows that tools such as ChatGPT can be effective as complements to the work

already produced by students and thus bring an additional dimension to the

educational process. It is essential, however, to stress the importance of

developing critical academic writing skills beforehand. The integration of

these technologies should be done in an approach that does not replace, but

rather complements and enriches students' analytical and creative skills in a

variety of academic and professional settings.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization,

K. B., J. C. D.-O.; Data curation, K. B., J. C. D.-O.; Formal Analysis, K. B.,

J. C. D.-O.; Investigation, K. B., J. C. D.-O.; Methodology, K. B.; Project

administration, K. B., J. C. D.-O.; Resources, K. B., J. C. D.-O.; software, K.

B.; Supervision, K. B., J. C. D.-O.; Validation, K. B., J. C. D.-O.;

Visualization, K. B., J. C. D.-O.; Writing – original draft: K. B., J. C.

D.-O.; Writing – review & editing, J. C. D.-O.

References

Acevedo,

E. N. (2023). La inteligencia artificial en la educación: una herramienta

valiosa para los tutores virtuales universitarios y profesores universitarios. Panorama, 17(32), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.15765/pnrm.v17i32.3681

Akiba, D., & Fraboni, M. C. (2023). AI-supported academic advising: Exploring ChatGPT’s current state and

future potential toward student empowerment. Education Sciences, 13(9), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090885

Aler T. A., Mora-Cantallops, M. & Nieves, J.C. (2024) How to teach responsible

AI in Higher Education: challenges and opportunities. Ethics Inf Technol 26, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-023-09733-7

Archila, P. A. (2015). Uso de

conectores y vocabulario espontaneo en la argumentación escrita: aportes a la

alfabetización científica. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de

las Ciencias, 12(3), 402-418. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090885

Bañales F. G., Vega L. N. A., Araujo A. N., Reyna V. A.,

& Rodríguez Z. B. S. (2015). La enseñanza de la argumentación escrita en la

universidad: una experiencia de intervención con estudiantes de lingüística

aplicada. Revista mexicana de investigación educativa, 20(66), 879-910.

Barrios-Tao,

H., Díaz, V., & Guerra, Y. M. (2021). Propósitos de la educación frente a

desarrollos de inteligencia artificial. Cadernos de Pesquisa, 51. Artículo e07767. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053147767

Bishop, L. (2023). A Computer Wrote This Paper: What ChatGPT Means for Education, Research,

and Writing. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4338981

Calle, K. M. Z., &

Mediavilla, C. M. Á. (2021). Tecnologías emergentes aplicadas a la práctica

educativa en pandemia covid-19. Revista Arbitrada Interdisciplinaria

Koinonía, 6(3), 32-59. https://doi.org/10.35381/r.k.v6i3.1303

Caro

Valverde, M. T., Amo Sánchez Fortún, J. M. de y Landow,

G. P. (2023). La educación del wreader en The Victorian Web: lecturas

dinámicas, comentarios argumentativos, curaduría infinita. Revista de

Educación a Distancia (RED), 23(75). https://doi.org/10.6018/red.544801

Carrera, F., Culque, W., Barbon, O.G., Herrera, L., Fernandez, E., &

Lozada, E. F. (2019). Autopercepción del desempeño en lectura y escritura

de estudiantes universitarios. Revista Espacios, 40(5).

Cassany,

D. (2019). Escritura digital fuera del aula: prácticas, retos y posibilidades

en Fuente F. A. (Ed.), Neuroaprendizaje e

inclusión educativa (pp.111-153). RIL Editores.

Chicaíza, R. M., Castillo, L. A. C., Ghose, G., Magayanes, I. E. C., & Fonseca, V. T. G. (2023).

Aplicaciones de Chat GPT como inteligencia artificial para el aprendizaje de

idioma inglés: avances, desafíos y perspectivas futuras. LATAM Revista

Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 4(2), 2610-2628. https://doi.org/10.56712/latam.v4i2.781

Cisneros-Barahona,

A.S., Marqués Molías, L., Samaniego Erazo, N., & Mejía Granizo, C.M.

(2023). La Competencia Digital Docente. Diseño y validación de una propuesta

formativa. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y

Educación, 68, 7-41. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.100524

de

la Cuesta-Benjumea, C. (2008) ¿Por dónde empezar?: la pregunta en investigación

cualitativa. Enfermería Clínica, 18(4),

205-210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1130-8621(08)72197-1

de

la Espriella, R. y Gómez, R., C. (2020). Teoría fundamentada. Revista

Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 49(2),

127-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2018.08.002

Degli-Esposti, S. (2021). El rol del análisis de género en la

reducción de los sesgos algorítmicos. ICE, Revista de Economía, (921). https://doi.org/10.32796/ice.2021.921.7265

Difabio de Anglat, H., &

Álvarez, G. (2017). Alfabetización académica en entornos virtuales: estrategias

para la promoción de la escritura de la tesis de posgrado. Traslaciones.

Revista Latinoamericana de Lectura y Escritura, 4(8), 97-120. https://revistas.uncu.edu.ar/ojs3/index.php/traslaciones/article/view/1066

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N.,

Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj,

A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah,

A. M., Koohang, A., Raghavan,

V., Ahuja, M., Albanna, H.,

Albashrawi, M. A., Al-Busaidi,

A. S., Balakrishnan, J., Barlette,

Y., Basu, S., Bose, I., Brooks, L., Buhalis, D., & Carter, L. (2023). “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary

perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative

conversational AI for research, practice and policy. International Journal

of Information Management, 71(102642)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642

García,

J. A. C., & Fernández, A. O. J. (2015). ¿Se está transformando la lectura y

la escritura en la era digital?. Revista interamericana de bibliotecología, 38(2), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rib.v38n2a05

Gerring, J. (2017). Qualitative Methods.

Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 15-36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-092415-024158

Gómez,

W. O. A. (2023). La Inteligencia Artificial y su Incidencia en la Educación:

Transformando el Aprendizaje para el Siglo XXI. Revista Internacional De

Pedagogía E Innovación Educativa, 3(2),

217–229. https://doi.org/10.51660/ripie.v3i2.133

González

V. M., & Romero R. R. (2022). Inteligencia artificial en educación: De

usuarios pasivos a creadores críticos. Figuras, revista académica de

investigación, 4(1), 48-58. https://doi.org/10.22201/fesa.26832917e.2022.4.1.243

Guzmán-Simón,

F. & García-Jiménez, E. (2015). La evaluación de la alfabetización

académica. RELIEVE, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.7203/relieve.21.1.5147

Hernández,

D., Cassany, D., & López, R. (2018). Prácticas

de lectura y escritura en la era digital. Editorial Brujas.

Jansen,

H. (2013). La lógica de la investigación por encuesta cualitativa y su posición

en el campo de los métodos de investigación social. Paradigmas: Una revista

disciplinar de investigación, 5(1),

39-72.

Kriscautzky, M., & Ferreiro, E. (2018). Evaluar la

confiabilidad de la información en Internet: cómo enfrentan el reto los nuevos

lectores de 9 a 12 años. Perfiles educativos, 40(159), 16-34. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2018.159.58306

Lara

V. R. S., Moreno O. T., & De Fuentes M. A. (2022). La argumentación escrita

y la estrategia de escritura colaborativa en el currículum de educación

superior. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 14(4), 521-530.

Leão, H. M. C., Gallo, J. H. da S., & Nunes, R.

(2022). La bioética se enfrenta hoy a enormes desafíos. Revista Bioética,

30(4). https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-80422022304000es

Leong,

K., Sung, A., & Jones, L. (2023). La tecnología central detrás y más allá

de ChatGPT: Una revisión exhaustiva de los modelos de

lenguaje en la investigación educativa. International Journal

of Educational Research and Innovation, (20),

1-22.

Limo,

F. A. F., Tiza, D. R. H., Roque, M. M., Herrera, E. E., Murillo, J. P. M., Huallpa, J. J. & Gonzáles, J. L. A. (2023). Personalized tutoring: ChatGPT as a virtual tutor for personalized

learning experiences. Social Space, 23(1), 293-312.

Maldonado

Alegre, F., Ulloa Córdova, V., Príncipe, Concha, B. y Trujillo-Solis, B. (2023). Comprensión lectora de textos argumentativos:

una revisión sistemática desde el nivel básico hasta el universitario. ReHuSo, 8(1),

132-145. https://doi.org/10.33936/rehuso.v8i1.4980

Malinka, K., Peresíni, M., Firc, A., Hujnák, O., & Janus, F. (2023). On the educational

impact of ChatGPT: Is Artificial Intelligence ready to obtain a university

degree? En Proceedings of the 2023

Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, 1,

47-53. https://doi.org/10.1145/3587102.3588827

Martínez-Comesaña, M., Rigueira-Díaz, X.,

Larrañaga-Janeiro, A., Martínez-Torres, J., Ocarranza-Prado,

I., & Kreibel, D. (2023). Impacto de la

inteligencia artificial en los métodos de evaluación en la educación primaria y

secundaria: revisión sistemática de la literatura. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 28,

93-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicoe.2023.06.002

Mateo-Girona,

M. T., Agudelo-Ortega, J. A., & Caro-Lopera, M. Á. (2021). El uso de

herramientas TIC para la enseñanza de la escritura argumentativa. Revista

Electrónica en Educación y Pedagogía, 5(8),

80-98. https://doi.org/10.15658/rev.electron.educ.pedagog21.04050806

Meana,

E. (2018). Lectura y escritura académicas en entornos digitales. Obstáculos

epistemológicos. Extensionismo, Innovación y Transferencia Tecnológica, 4, 129-135. https://doi.org/10.30972/eitt.402881

Melo-Solarte,

D. S., & Díaz, P. A. (2018). El aprendizaje afectivo y la gamificación en

escenarios de educación virtual. Información

tecnológica, 29(3), 237-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07642018000300237

Molina,

M. E., & Carlino, P. (2013). Escribir y

argumentar para aprender: las potencialidades epistémicas de las prácticas de

argumentación escrita. Texturas, 13(1),

16-32.

Moore,

P., & Andrade Mayer, H. A. (2016). Estudio contrastivo del género

discursivo del ensayo argumentativo. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 18(2), 25-38. https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.9204

Navarro, F. (2019). Aportes para una

didáctica de la escritura académica basada en géneros discursivos. DELTA: Documentação de Estudos em Lingüística

Teórica e Aplicada, 35. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-460X2019350201

Ocaña-Fernández,

Y., Valenzuela-Fernández, L. A., & Garro-Aburto, L. L. (2019). Inteligencia

artificial y sus implicaciones en la educación superior. Propósitos y

representaciones, 7(2), 536-568. http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2019.v7n2.274

Ortiz,

A. C. E. (2023). Uso de ChatGPT en los manuscritos

científicos. Cirujano General, 45(2),

65-66. https://dx.doi.org/10.35366/111506

Padilla,

C. y Carlino, P. (2010). Alfabetización académica e

investigación-acción: enseñar a elaborar ponencias en la clase universitaria.

En G. Parodi Sweis (Ed.). Alfabetización académica

y profesional en el siglo XXI: leer y escribir desde las disciplinas

(pp.153-182). Ariel.

Perkins,

D. (2014). Future Wise: Educando a Nuestros Hijos

para un Mundo Cambiante. Jossey-Bass.

Prieto-Andreu, J. M., & Labisa-Palmeira, A. (2024). Quick Review of Pedagogical

Experiences Using GPT-3 in Education. Journal of Technology and Science

Education, 14(2), 633-647.

Ramos, J. R. G. (2018). Cómo se

construye el marco teórico de la investigación. Cadernos de pesquisa, 48, 830-854. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053145177

Ros-Arlanzón,

P., & Pérez-Sempere, Á. (2023). ChatGPT: una novedosa

herramienta de escritura para artículos científicos, pero no un autor (por el

momento). Revista de Neurología, 76(8),

277. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.7608.2023066

Ruaro, R. L., & Reis, L. C. C. G. (2020). Los retos

del emprendimiento en la era de la inteligencia artificial. Veritas, 65(3). https://doi.org/10.51660/ripie.v3i2.133

Sánchez, O. V. G. (2023). Uso y Percepción

de ChatGPT en la Educación Superior. Revista de Investigación

en Tecnologías de la Información, 11(23),

98-107. https://doi.org/10.36825/RITI.11.23.009

Selwyn, N., Rivera-Vargas, P., Passeron, E., & Puigcercos, R. M. (2022). ¿Por qué no todo es (ni debe ser)

digital? Interrogantes para pensar sobre digitalización, datificación

e inteligencia artificial en educación. Octaedro, 137-147. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/vx4zr

Simó,

V. L., Lagarón, D. C., & Rodríguez, C. S. (2020).

Educación STEM en y para el mundo digital: El papel de las herramientas

digitales en el desempeño de prácticas científicas, ingenieriles y matemáticas.

Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED), 20(62).

Taylor,

S. J., & Bodgan, R. (1984). La observación

participante en el campo. Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de

investigación. La búsqueda de significados. Paidós Ibérica.

Vera,

F. (2023). Integración de la Inteligencia Artificial en la Educación superior:

Desafíos y oportunidades. Transformar, 4(1), 17-34.

Vera, J. P. D., Hojas, D. S. P., Sarmiento, Z. J. F., Ramírez, A. K. R.,

& Mora, D. V. M. (2023). Estudio comparativo experimental del uso de chatGPT y su influencia en el aprendizaje de los

estudiantes de la carrera Tecnologías de la información de la universidad de

Guayaquil. Revista Universidad de Guayaquil, 137(2), 51-63. https://doi.org/10.53591/rug.v137i2.2107

Vicente-Yagüe-Jara,

M.I., López-Martínez, O., Navarro-Navarro, V., & Cuéllar-Santiago, F.

(2023). Writing, creativity, and artificial

intelligence. ChatGPT in the university context. Comunicar, 77, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.3916/C77-2023-04

Villarroel,

C., García-Milà, M., Felton, M., & Banda, A. M.

(2019). Efecto de la consigna argumentativa en la calidad del diálogo

argumentativo y de la argumentación escrita. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, Infancia

y Aprendizaje, 42(1), 37-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2018.1550162

Woo, L. J., Henriksen, D.,

& Mishra, P. (2023). Literacy as a Technology: a Conversation with Kyle

Jensen about AI, Writing and More. TechTrends, 67(5), 767-773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00888-0

Zhu, J.-J., Jiang, J., Yang,

M., y Ren, Z. J. (2023). ChatGPT and Environmental

Research. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(56), 17667-17670. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.3c01818421